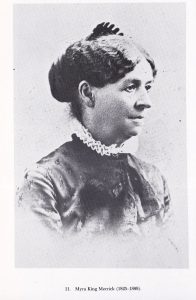

photos: (l) Dr. Myra King Merrick (r) Dr. Sarah Marcus

Roads Less Traveled:

Cleveland’s Women Doctors, 1852-1984

by Marian J. Morton

The pdf is here

It’s not easy to become a doctor; the road is long and hard. For generations of women, it was longer and harder. But not impossible. Challenged by cultural and institutional obstacles, these Cleveland women chose alternative routes to their profession. Often barred from medical schools and hospitals, they established their own; often unwelcome in established medical specialties, they laid claim to others; often sidelined in public life, they remained politically committed to women’s causes. These doctors took the roads less traveled.

Background

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate from a medical school – Geneva Medical College – in 1847. Her graduation was unusual for two reasons: first, the usual route to becoming a doctor – like that of becoming a lawyer – was through an apprenticeship with an older, more experienced practitioner – not by going to medical school. Second, although by the 1820s, there were a dozen medical schools – at Harvard, University of Pennsylvania, Dartmouth, Yale, and Georgetown, for example, – none admitted women. Women were considered too fragile, intellectually and physically unable to tackle the rigors of higher education. This popular wisdom was reinforced by experts such as Harvard’s Dr. E.H. Clarke, whose Sex in Education: A Fair Chance for Girls argued in 1873 that studying impaired women’s reproductive organs, denying them the maternal role that was a woman’s true destiny. In any case, so the rationale continued, even if they were willing to risk infertility, women should be too modest to sit in the same classrooms as men studying such things as human anatomy.

Blackwell’s admission into Geneva, a small school in upstate New York, was a prank played by the students upon the faculty. Extremely reluctant to accept her, the faculty allowed students to vote on Blackwell’s admission. “The ludicrousness of the situation seemed to seize the entire class, and a perfect Babel of talk, laughter, and cat calls followed,” recalled one young man. To the faculty’s dismay, the students voted yes. [1] Despite the subsequent hostility and harassment, Blackwell graduated at the top of her class. The college then shut its doors to women.

Blackwell also created the career path that other women would follow. Finding it difficult to compete with male doctors, she specialized in the care of women and children, taking advantage of the very cultural norms that had been barriers to her education. Women were thought to have the innately nurturing qualities appropriate for pediatrics: after all, women were born to be mothers. And the very modesty that prevented them sharing the classroom with men meant that a woman patient should be treated only by other women. These were not medical specialties that paid well. After her graduation, Blackwell established the New York Infirmary for poor women and children.

Geneva Medical College was a “regular” or “allopathic” institution. Most regular medical schools required 32-40 weeks of lectures and an apprenticeship and boasted a curriculum based on what mid-nineteenth century Americans knew about chemistry, human anatomy, surgery, and bacteriology. Common medical practices by regularly trained doctors also included “heroic” measures such as bleeding, leeches, and harsh emetics.

In 1847, the nascent American Medical Association (AMA) urged that regular schools also include clinical instruction. This effort to establish rigorous standards for the profession was a response to the mid-century proliferation of doctors and the medical institutions that produced them, a proliferation encouraged by lax state licensing laws and the uncertainty about what exactly cured what. Many of these new schools were proprietary or for-profit. Many taught alternative therapies. Regulars or “allopaths” referred to these latter competitors as “irregular” or “sectarian,” suggesting their quackery and illegitimacy.

These therapies, like allopathic medicine itself, reflected the widespread desire to improve American health. Health reforms included temperance (abstinence from alcohol), diet reform (vegetarianism and Grahamism); herbalism (reliance upon age-old natural remedies); hydropathy (cure by drinking or immersion in water), or the most tenacious, homeopathy (based upon the theory that diseases can be cured by very small doses of drugs that produce the same symptoms as the disease – that is, like cures like). While the regulars charged that these remedies were ineffective, they at least followed the ancient medical dictum, “do no harm,” which is more than could be said of bleeding or emetics.

The irregular institutions were – at least initially – happy to accept women, and when irregular institutions joined the regulars in excluding women, women sometimes established their own – the Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College for Women, for example. Most of the women’s schools were short-lived, dying or merging with regular medical institutions, for financial reasons. [2] By the end of the century, state universities’ medical schools began to admit women – the University of Michigan was the first. And persuaded by a large gift dependent on admitting women, the medical school of John Hopkins University, the standard-bearer for all higher education, became coeducational in 1893.[3]

In 1910, educator Abraham Flexner’s famous report criticized the mediocre quality and the profit motive of much medical education, recommending that students have at least a high school degree and two years of college before entering medical school and that medical students receive in-hospital clinical training. His particular targets were the “sectarian” and for-profit schools. In the wake of his report, dozens of medical schools merged or closed, many of them “irregulars,” women’s historic route into the profession. [4]

Nevertheless, by 1910, 6 percent of all doctors were female. Cleveland women showed how this could happen.

First Graduates

The Cleveland Medical College in 1852 graduated its first woman, Dr. Nancy Talbot Clarke. The medical college was affiliated with Western Reserve College, located in Hudson, Ohio. (After Western Reserve College moved to University Circle in 1882, the medical school became the Western Reserve University (WRU) School of Medicine.) Clarke managed to graduate despite the hostility of the faculty, who in 1851 had unanimously supported the motion that “it is inexpedient to admit female students to our lectures.” A handful of other women braved this inhospitable atmosphere, and six were graduated by 1856. [5] Among them were Dr. Emily Blackwell, Elizabeth Blackwell’s sister, and Dr. Marie Zakrzewski. Both went to work at Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell’s infirmary in New York City. Zakrzewski then went to Boston, where she founded an institution similar to the Blackwells’, the New England Hospital for Women and Children in 1862.

The AMA in 1856, fearful that female physicians would lower the status of the new profession, adopted a resolution against coeducation. Although a few women managed to graduate during the 1870s from the Cleveland Medical College, it resurrected – and enforced – , the 1851 policy beginning in the mid-1880s.[6] No women were admitted until 1918 when the dwindling enrollment of male students due to the United States entrance into World War I inspired a change of heart and admissions policy.

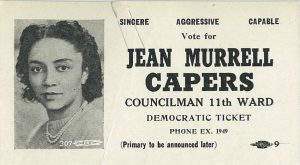

Dr. Myra King Merrick (1825-1899)

Merrick was Cleveland’s first woman physician. When she hung out the shingle advertising her services in 1852, “no circus bill ever attracted more curious attention.” The daughter of English immigrants, Merrick herself began to work in the textile mills near Boston at age 8. She married in 1848. (Until her divorce in 1880, she was referred to as “Mrs. Dr. Merrick.”) Her husband’s illness “compelled her to become the breadwinner. She conceived the idea that the practice of medicine would be a lucrative calling.” [7] Her colleague Dr. Martha Canfield explained: “While she was full of quiet determination, her gentle, womanly manners disarmed opposition …. She was only like many other women, driven to fight the battle of life alone.”[8]

Barred from regular medical schools, Merrick studied first at a hydropathic institute and graduated in 1851 from the Central Medical College of Rochester, an eclectic institution that leaned toward homeopathy.

Homeopathy had a substantial following in northeast Ohio. Its method – minuscule doses of non-toxic substances – addressed what homeopaths considered the prevalent “overtreatment of patients with drugs about which doctors knew little, for diseases about which they knew less.” It enlisted distinguished male and female physicians, attracted wealthy clients such as John D. Rockefeller, and built substantial institutions. The Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital opened in 1856, the first organized hospital in Cleveland. This was re-named Huron Street Hospital and eventually Huron Road Hospital. It moved in 1935 to Terrace Road in East Cleveland at the foot of Rockefeller’s Forest Hill estate. The hospital’s prestigious board of trustees included Mark Hanna and Myron R. Herrick. [9]

In 1867, Cleveland’s Western Homeopathic College decided to improve its reputation by refusing to admit women. Merrick and other women then established the Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College for Women; she served on its faculty and as its president until it merged with the original institution in 1871 to form Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College. (In 1911, the college became Pulte Medical College, allied with Ohio State University, until the latter ended its homeopathic program in 1922.)

Merrick’s own experiences, private and professional, explain her advocacy of woman’s causes, popular and unpopular. Her medical studies in up-state New York, not far from Seneca Falls, the site of the world’s first woman’s rights convention in 1848, may also have inspired her. In 1869, Merrick was elected president of the Cuyahoga County Woman Suffrage Association at a meeting attended by 100 courageous women and a few even more courageous men. The group drew up a constitution, whose preamble echoed the Seneca Falls Declaration: “Believing in the natural equality of the two sexes, and that woman ought to enjoy the same legal rights and privileges as man; [and] that as long as women are denied the elective franchise they suffer a great wrong, … the undersigned agree to unite in an association to be called ‘The Cuyahoga County Woman Suffrage Association.’” This radical step must have put Merrick’s new medical practice at risk.

In further pursuit of equal opportunities for her sex, Merrick, with Dr. Eliza Merrick, her daughter-in-law, and Dr. Martha M. Stone, in 1878 founded the Women’s and Children’s Free Medical and Surgical Dispensary that operated out of the Homeopathic Hospital College. Its purpose was to provide poor women and children – “the worthy sick poor” – with much-needed medical treatment and to provide female doctors with much-needed clinical experience. The dispensary staff also visited patients’ homes, providing advice on hygiene and nutrition and occasionally even employment. [10]

The only other place that provided medical care to Cleveland’s indigent was the city Infirmary, more commonly referred to as the poorhouse. It was intentionally an inhospitable place to discourage long-time residence at taxpayers’ expense. It was called the Infirmary because most who entered had been made indigent by their own illness or the illness of the family breadwinner. Inmates were disproportionately women and children. [11] Hence, the necessity of privately funded charitable institutions such as Merrick’s dispensary.

Despite her charitable and political activities, medicine had – as Merrick had hoped – proved to be a lucrative calling. She made money – and lots of it. “[H]er skill, her serene confidence in herself …, and her dogged persistence triumphed , … and for many years she stood shoulder to shoulder with the best physicians in the city. More than this, she overstepped most of them in a pecuniary way, and her practice, largely, was among a wealthy and exclusive class that gave her an income far up in the thousands.”[12] Merrick was “the mother of all the women physicians at the present,” declared Canfield in 1896. [13]

Dr. Martha Canfield (1845-1916)

Canfield herself was one of Merrick’s “children,” following and building upon Merrick’s pioneering. She graduated from Oberlin College in 1868. She married attorney Harrison Wade Canfield in 1869, and the couple had four children. Medicine was her second career choice. She taught school before entering the Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College. After her graduation in 1875, she became professor of gynecology at the college, 1890-1897.

Both the practice and the teaching of gynecology were wide open fields for women doctors. Few female patients would welcome an examination by a male doctor: “Many physicians entered practice without ever having seen a baby born.” By the early twentieth century, when gynecology and obstetrics were finally taught in medical schools, students were urged not to specialize in them because they paid so badly: “That man who undertook to be a pure specialist in this department, in this city, would soon find himself a candidate for the poor house or the State Hospital [for the insane].” [14]

Canfield was an outspoken advocate for women’s causes. In 1886, she addressed the Western Reserve Club on “The Divorce Mania.” The cure for the rising number of divorces, she argued, would be “giving woman more responsibilities as well as more rights.”[15] She also spoke on the “evils of intemperance,”[16] which fell more heavily upon women than men. Another target: “houses of ill fame” that spread disease among innocent women and children as well as guilty men. [17]

She served on the medical staff of the Maternity Hospital, established in 1891. Like most hospitals and like the dispensary, this was a small, privately funded charitable institution; it was initially homeopathic, intended for an indigent clientele, and specializing in obstetrics. In 1917, it affiliated with the WRU School of Medicine and became an allopathic or regular institution. In 1925, by then the largest maternity facility in Cleveland, the hospital moved to University Circle and became MacDonald House of University Hospitals. Its gradual transformation foreshadowed imminent changes for women physicians and women’s health care. [18]

Canfield succeeded Merrick as the director of the women’s and children’s dispensary in 1900. Its 1909 annual report provides an intimate look into the dispensary’s unique role: “Many times have mothers come contemplating embryonic or fetal destruction, and asking assistance, thinking women physicians more easy to approach on the subject. Each time they left wiser than when they came and nearly always persuaded to follow the safer and more righteous course.” [19] Whatever the doctors’ moral compunctions about abortion, carrying a child to term would certainly have been “safer” than the available methods of self-induced abortion.

Since most regular hospitals did not permit women on staff, the Flexner 1910 report’s mandate for in-house clinical experience created an enormous challenge. The result: Woman’s Hospital, an expansion and institutionalization of Merrick’s dispensary in 1912. The facility had 12 beds and an annual budget of $5,000. It was staffed by both homeopathic and allopathic, male and female doctors to provide women with the required clinical skills in a hospital setting. The hospital served men, women, and children, and unlike the dispensary, it was not free although it took some charity patients. [20]

When Canfield died in 1916, she was memorialized by the local Homeopathic Medical Society: “the medical profession has lost a representative and talented physician and all who knew her will miss the inspiration and helpfulness of her friendship.”[21] In addition to her family, she left behind an institution and a profession that would continue to change for women.

Dr. Lillian Gertrude Towslee (1859-1918)

Towslee succeeded Canfield as president of Woman’s Hospital in 1916. She is an important transitional figure in the history of Cleveland’s women doctors because she trained and taught at regular medical institutions.

Like Canfield, she graduated from Oberlin – its Conservatory of Music – in 1882. (She hosted and entertained at musical social events all her life.) She graduated in 1888 from Wooster University Medical College in Cleveland. (The school later merged with WRU School of Medicine.) She taught briefly at the Wooster University Medical College and also at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ohio Wesleyan University, both regular institutions. Like Canfield, she specialized in gynecology, but also trained as a surgeon. Her regular medical education probably got her accepted into the probably all-male Academy of Medicine of Cleveland, founded in 1902. [22]

In an 1893 article for the Western Reserve Medical Journal, “Why Women Should Practice Medicine,” she explained her choice of gynecology: this is “woman’s especial sphere…. A woman understands the sensitiveness of a woman and appreciates the suffering she endures better than is possible for a man.… Women are especially adapted to care for the sick.” Yet she was candid about the difficulties that women, certainly including herself, faced: “To gain any standing a woman was obliged to compete with the better class of physicians [probably a reference to her training.] …. She at first met with great opposition. Men did not want her in the profession and placed every obstacle in her path. She has fought her way step by step and won the day,” she concluded optimistically. [23]

Like Merrick and Canfield, Towslee was a political activist. A member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, she turned down an invitation from the Prohibition Party to run as their candidate for Cleveland School Council. [24] (Ohio women could participate in elections for school board candidates.) She was also an enthusiastic suffragist and hostess at a 1902 suffrage convention in Cleveland. The honored guests included Susan B. Anthony. One keynote speaker accurately predicted, “Suffrage would not be a shortcut to the millennium, but it would be a step forward.” [25]

Towslee also hosted the Political Equality League, whose members heard a spirited lecture by suffragist Mrs. Frederic C. Howe on the need to rationalize household drudgery so that women could play a more active public role. [26] According to the local newspaper, however, Towslee was less newsworthy for her professional and political achievements than for a five-week automobile trip that she took with her companion, Mrs. Katherine Arthur, her stepson, George and two young friends in 1911. Of apparent interest to the reading public: the fact that the group camped outside every night and never ate or slept under a roof. Also notable: the unreliable nature of automobiles in 1911. A chauffeur did some of the driving. [27]

Towslee headed Woman’s Hospital only until her death in 1918. Not long enough to leave her personal imprint on the institution, but long enough to give it the respectability of allopathic medicine, which it would need, going forward.

Dr. Merriam Kerruish Stage ( 1870 – 1929)

Stage helped guide Woman’s Hospital through its next phases. Like Towslee, Stage was regularly trained. After graduation from Smith College in 1892, she enrolled at the Wooster University Medical College, finishing her degree in 1895.

She established her practice as a gynecologist and pediatrician and also served on the staff at Cleveland City Hospital in 1895. The facility had only recently separated from the city Infirmary. Like the poorhouse, City Hospital cared for indigent patients. Nevertheless, the hospital did not employ a full staff of physicians until 1891. [28] Stage may well have been the first female physician on that staff, and her experience there may explain her subsequent belief that the illnesses she treated as a pediatrician could be blamed on poverty. [29]

Stage married attorney Charles W. Stage in 1903, and they had four children. It is not clear whether she returned to her medical practice. Newspaper and other accounts refer to her as “Mrs. Stage”, not “Dr. Kerruish.” But she remained committed to women’s causes and institutions.

She marched proudly in the splendid parade of 10,000 suffragists from 64 Ohio cities and counties in October 1914 as bystanders and marchers anticipated – too optimistically – the passage of an amendment to the state constitution that would enfranchise women. [30] It would be another six years before the passage of the Nineteenth (Woman Suffrage) Amendment, but Stage remained active in politics, joining the local League of Women Voters after its founding in 1920.

She also became a forceful advocate for women and children. She was chosen vice-president of the Women’s Protective Association that pushed for a temporary detention facility for first-time female offenders: “Women Steeped in Crime Mix with Mere Girls at Central Station,” explained the newspaper account.[31] She joined the Consumers League of Ohio, dedicated to improving the living and working conditions of women and children. Reflecting her medical training, she served on the committee that made it “their task to find a way to get this prime necessity of life [milk] to the children.”[32]

Woman’s Hospital in the meantime had expanded its scope, staff, and number of beds, moving to a new building on E. 101st St. in 1918. On its staff were nine female physicians and eleven male physicians; two more women and two men served in the clinic department. In 1926, the hospital had been accredited for the training of interns and had strong financial support from the local community. [33]

Stage, one of those benefactors and a member of the hospital’s all-female, all-physician board of trustees, pushed to enlarge the board by including non-medical men and women, broadening the board’s scope and financial resources. She remained particularly interested in internships for women doctors.[34]

Stage died tragically in the May 1929 fire at the Cleveland Clinic. A memorial fund, established by Mrs. Charles Thwing, raised $14,621 in her memory. The funds were used to make the last payment on Woman’s Hospital’s mortgage in 1934, her final contribution to the institution. [35]

Dr. Ruth Robishaw Rauschkolb (1900-1981)

Robishaw took women’s health in a new, unprecedented direction, helping women take control of their fertility; she became a pioneer in family planning. A Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Ohio State University, she also graduated at the top of her class at the WRU School of Medicine in 1923, specializing in dermatology. Although she did an internship at City Hospital, her age and gender prevented her from doing her residency there. [36] She taught in both the pediatric and the dermatology departments of WRU School of Medicine. She practiced dermatology with her husband under his name, Rauschkolb, but used her maiden name in her controversial position as a founder of the clinic of the Cleveland Maternal Health Association, the forerunner of Planned Parenthood of Greater Cleveland.

According to legend, the clinic was inspired by the suicide of a young woman, pregnant and already overburdened with nine children. Volunteers at a pre-natal clinic, Dorothy Brush and Hortense Shepard, were outraged, but felt powerless because the 1873 Comstock Law made illegal the distribution of birth control technology and information.[37] Violation of the law had jailed many – most famously, Margaret Sanger, the founder of the birth control movement, – and in Cleveland, Ben Reitman, the lover and manager of anarchist Emma Goldman in 1916.

Quite correctly, the birth control movement was associated with the political left and free love. During the 1920s, however, the movement gained a measure of respectability as it shifted its emphasis away from a woman’s right to control her own body to society’s need to control the size and quality of its population. Cleveland illustrates this transition. In 1923, the Maternal Health Association was formed at the Women’s City Club. Members tried – without success – to get birth control information distributed at local hospitals. [38] In 1928, however, inventor Charles F. Brush donated $500,000 to a foundation dedicated to ending over-population. His goal was eugenics – limiting population growth “which threatens to overcrowd the earth in the not distant future,[39] not liberating women’s sexuality or improving women’s health. Nevertheless, the foundation assisted his daughter-in-law’s Maternal Health Association, which opened its first clinic that year. The clinic had to have a medical staff: Robishaw became the first director, assisted by Rosina Volk, R.N.. Both risked their careers.

Initially the clinic served only married women, seeing 510 clients between 1928-1930. [40] Although the Depression made family limitation an acceptable – and necessary – option, the association still fought “the medical conservatism” of the AMA on birth control in 1933. [41] The clinic continued to expand its clientele and mission, offering marriage counseling in the 1930s and advice on infertility in the 1940s.

Robishaw became the public face of the clinic, as it struggled for respectability, boldly bringing its message to a wide variety of audiences. “Sex and Marriage” was her topic at the YMCA in May 1936; she also addressed local PTA’s on “The Wanted Child,” and as part of a program on “The Family and Sex Education,’ she spoke on ‘Personal Regimen for Women.”[42] In October, 1940, she addressed the Women’s Association of the Temple on “The Biological Basis of Marriage.”[43]

Robishaw was elected third vice president of the American Medical Women’s Association in 1941. The group demanded equal treatment in the military, as the United States approached entrance into World War II: “… the United States government to date had taken no cognizance of … women physicians in time of war;” the association asked that women “become eligible for the medical reserve corps of the United States Army and Navy with full privileges enjoyed by men physicians.”[44]

Robishaw returned to private practice but remained on the medical advisory board of the Maternal Health Association. The association had affiliated with the national Planned Parenthood organization in 1942 and changed its name to Planned Parenthood of Greater Cleveland in 1966.

Dr. Sarah Marcus (1894-1985)

Marcus witnessed the affiliation of the small, renegade birth control clinic with this national organization and the demise of the venerable institution created especially for women doctors, Woman’s Hospital.

She graduated from Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve University in 1916 but was turned down by its medical school. She went instead to the University of Michigan, graduating in 1920. Many years later when she became the first woman to receive the University of Michigan Distinguished Alumnus Award, Marcus recalled with wry amusement her rejection by Western Reserve. Dean Dr. Frederick C. Waite kept Marcus waiting for her interview “a long time, and finally, since I didn’t leave, I was admitted to his office.” He couldn’t accept her, he explained, because “the school did not have any toilet facilities for women! I promised not to need them.” Waite remained un-persuaded. President Charles Thwing agreed to admit her if she could convince five other women to apply. She couldn’t. Even with legal assistance from Judge Florence Allen, the doors to the medical school remained closed to women. [45] Until two years later when the shortage of male students changed the administration’s mind.

After a residency at Ohio City Hospital in Akron, she joined the outpatient staff at Mount Sinai Hospital as a gynecology-obstetrician in 1923. In 1928, she studied in Vienna with a student of Dr. Sigmund Freud. Like Robishaw, Marcus was an outreach speaker for the Maternal Health Association to local PTA’s and women’s organizations. She established a clinic on infertility and addressed the American Medical Women’s Association in 1962 on “Medical Aspects of Marriage and the Family.” [46]

Marcus herself married twice and claimed to have had no difficulty combining her career with marriage and motherhood. Two weeks after the birth of her son, she recalled, her own doctor stopped to see her and her new infant. Marcus was out, however, delivering someone else’s baby. She lost track, she said, of the number of children she delivered over the course of her long career. [47]

Like the other women doctors in this study, she dedicated much of her professional life to promoting opportunities for other women. She established the Women’s Medical Society of Cleveland in 1929, and even more forcefully than Canfield, Towslee, and Stage, Marcus played a leadership role at Woman’s Hospital. She headed its department of obstetrics and gynecology from 1933 to 1950 and served on its board of trustees, as vice-president, 1932-1958, and president, 1958-1971. As board president, she oversaw the expansion of the hospital’s facilities and services. The hospital changed its name to Woman’s General Hospital in 1970, suggesting a broadening of its clientele and services. The board remained predominantly female, but fewer and fewer of the medical staff were women.

Marcus remained optimistic in 1976: “Woman’s Hospital had a mission and that mission is fulfilled. No longer do women need their own hospital for protection from derision and insults or for the opportunity of obtaining good internships and residency.” In striking contrast to her own experience, she concluded, women are accepted everywhere. [48]

The hospital itself, however, faced with mounting competition, dwindling patients, and failure to get a contract with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Northern Ohio, closed its doors in 1985. Its program for female alcohol and drug abusers, known as Merrick Hall after Cleveland’s pioneer woman doctor, was transferred to Huron Road Hospital – appropriately enough the offspring of the homeopathic institutions that had admitted women more than a century earlier. [49]

The Road Forward

It wasn’t easy for a woman to become a doctor – to risk being childless, as Dr. E. H. Clarke threatened; to arouse “laughter and cat calls” when you applied to medical school as Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell did; to brave a medical school faculty who thought it “inexpedient” for you to be there, as did the first women graduates of WRU School of Medicine; to arouse curiosity worthy of a “circus bill” when you hung up your shingle like Dr. Myra King Merrick; to have to overcome “every obstacle” that men placed in your path, as did Dr. Lillian Gertrude Towslee; to be denied admission to medical school because “the school did not have any toilet facilities for women,” like Dr. Sarah Marcus. But these women did it.

It still isn’t easy for a woman to become a doctor; the road is still long and hard. But if it is less hard today, it is partly because these women who traveled it decades ago rose to the challenges and fought for themselves and for the women who followed them on the roads less traveled. *

Marian J. Morton is a professor emeritus at John Carroll University. She received her B.A. in classics from Smith College and her M.A. and Ph.D. in American studies from Case Western University. She is the author of And Sin No More: Social Policy and Unwed Mothers in Cleveland, 1855–1990; Emma Goldman and the American Left: “Nowhere at Home”; The Terrors of Ideological Politics: Liberal Historians in a Conservative Mood; Women in Cleveland: An Illustrated History and Cleveland Heights: The Making of an Urban Suburb.

* This essay is dedicated to Dr. Hannah Z. Kooper-Kamp, who is traveling that road, and to her husband, my grandson, James W. Garrett IV, who travels with her all the way.

[1] Regina Markell Morantz -Sanchez, Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 49.

[2] Mary Roth Walsh, Doctors Wanted: No Women Need Apply: Sexual Barriers in the Medical Profession, 1835-1975 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1977), 180.

[3] Morantz-Sanchez, 87.

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235368754_The_Flexner_Report_of_1910_and_Its_Impact_on_Complementary_and_Alternative_Medicine_and_Psychiatry_in_North_America_in_the_20th_Century . The medical schools that admitted blacks were reduced from 10 to three in the wake of the report: http://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/3086/Abraham%20Flexner%20black%20medical%20schools.pdf.

[5] Frederick Clayton Waite, Western Reserve University Centennial History of the School of Medicine (Cleveland: Western Reserve University Press, 1945), 126-127.

[6] Adelbert College of Western Reserve ended coeducation at almost exactly the same time . Hiram C. Hayden became president of the college in November 1887 and terminated the admission of women shortly afterwards. A separate undergraduate College for Women was established in 1888, but no separate medical school for women was forthcoming.

[7] Cleveland Plain Dealer (CPD), June 28, 1896: 3.

[8] CPD, June 28, 1896:3.

[9] Victor C. Laughlin, “Homeopathy” in Kent L. Brown, ed., Medicine in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, 1810-1976 (Cleveland : The Academy of Medicine of Cleveland, 1977), 46-51; the quote is on page 47.

[10] Glen Jenkins, “Women Physicians and Woman’s General Hospital’ in Brown, ed., 55.

[11] Marian J. Morton, And Sin No More: Social Policy and Unwed Mothers in Cleveland, 1855-1990 (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1993), 24-33.

[12] CPD, November 11, 1899: 3.

[13] CPD, June 27, 1896: 5.

[14] Burdett Wylie, “Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Cleveland Hospital Obstetric Society” in Brown, ed., 232-273; the quote is on p. 239. Wylie does not mention one woman physician in this essay.

[15] CPD, November 18, 1886: 5.

[16] CPD, November 9, 1893: 8.

[17] CPD, May 15, 1894: 6.

[18] Morton, 111-112

[19] Quoted in Jenkins, 56.

[20] Jenkins, 59.

[21] CPD, September 6, 1916: 7.

[22] https://case.edu/ech/articles/t/towslee-lillian-gertrude-md/

[23] Mrs. W.A. Ingham, Women of Cleveland and Their Work: Philanthropic, Educational, Literary, Medical, and Artistic (Cleveland, O: W.A. Ingham, 1893), 326.

[24] CPD, February 7, 1898: 1.

[25] CPD, October 9, 1902: 5.

[26] CPD, February 15, 1907: 7.

[27] CPD, September 24, 1911: 60.

[28] Morton, 111-112.

[29] http:// teachingcleveland.org/Miriam-kerruish-stage-biography/

[30] Virginia Clark Abbott, The History of Woman Suffrage and the League of Women Voters in Cuyahoga County, 1911-1945 (Cleveland: n.p., c . 1949), 33.

[31] CPD, October 14, 1917: 10.

[32] CPD, October 12, 1919: 57.

[33] Jenkins, 62-63.

[34] Jenkins, 61-62.

[35] Jenkins, 64.

[36] http://case.edu/ech/articles/r/rauschkolb-ruth-robishaw-md/

[37] David R. Weir, “”Planned Parenthood, 1923-1976” in Brown, ed., 274.

[38] Weir, 274-275.

[39] CPD, June 21, 1928: 3.

[40] http://case.edu/ech/articles/planned-parenthood-of-greater-cleveland/

[41] CPD, October 7, 1933: 4.

[42] CPD, January 9, 1939: 29; and March 19, 1939: 37.

[43] CPD, October 29, 1940: 14.

[44] CPD, June 3, 1941: 15.

[45] Quoted in Jenkins, 67.

[46] CPD, November 18, 1962: 13.

[47] CPD, May 13, 1985: 47.

[48] Quoted in Jenkins, 68-69.

[49] Woman’s General was only one of many small independent hospitals that failed or merged in the last decades of the twentieth century because of financial problems. Huron Road Hospital itself in 1984 had merged with Hillcrest and Euclid General Hospitals in an unsuccessful effort to remain financially viable. All were absorbed into the Cleveland Clinic, which closed the Huron Road facility in 2011. Two hospitals with beginnings similar to Woman’s General also closed. Forest City, established in 1939 so that black doctors, unwelcome elsewhere, could receive training and treat patients, closed in 1978. Mount Sinai Hospital, founded in 1913 and intended for Jewish doctors and patients, closed in 2000.