Frank C. Cain, Cleveland Heights, and the Suburban Vision

by Marian J. Morton

The pdf is here

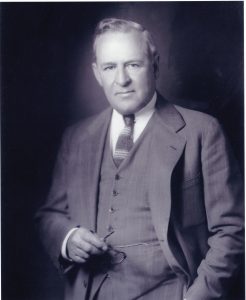

Handsome, outgoing, and outspoken, Cleveland Heights Mayor Frank C. Cain became a prominent booster for the early twentieth-century vision of suburbia: an escape from the city – its congestion, unhealthy pollution, visible poverty, and uncongenial neighbors – to green spaces and tree-lined streets of single-family homes for nicer people. Cain’s was hardly an original vision of suburbia: it was widely shared by ambitious realtors and upwardly mobile suburbanites. But as the acknowledged leader of local suburban officials, Cain defined and defended his vision; as the long-time, powerful elected mayor of the biggest suburb around, Cain tried to turn the vision into reality.

In 1900, Cain and his wife moved to a relatively isolated southwest corner of East Cleveland Township. A year later, this became Cleveland Heights, a country village on the verge of suburbanization as landowners enthusiastically began to turn their orchards, farms, and quarries into residential developments with names that suggested their elevated social status. In 1909, when Cain purchased his first home on Radnor (then Florence) Road in the Mayfield Heights allotment, just east of Coventry Road, a realtor glowingly described its suburban charms: “Mayfield Heights … Country Life in Cleveland …. Delightful surroundings, … high above the level of the lake where the air is pure. GOOD neighbors, sensible restrictions, nearness to schools, churches, and stores of all kinds.” [1] (Restrictions referred to the size of the lots, the setbacks from the street, and the residential-only use of the properties.) Fifteen years later, Cain moved to Compton Road, another ideal suburban location and presumably a step up the social ladder: “Compton Heights …. Our lots are all large …; our restrictions insure only the most desirable class of residents;” “COMPTON HEIGHTS … FINE TREES… MANY FINE HOMES. “ [2]

1900-1919: Rising Star

Cain quickly became involved in local affairs, joining the Men’s Civic Club, the movers and shakers of this village of about 1,500. The club was formed at the Presbyterian church (now Forest Hill Church Presbyterian) that first met just down the street from Cain’s home on Radnor. He probably joined the church too. Also nearby were a small Methodist church (now Church of the Saviour) at Superior and Hampshire Roads and a mid-nineteenth-century one-room schoolhouse at Superior and Euclid Heights Boulevard. Radnor was only a five-minute walk to the city hall on Mayfield Road, which remained the center of Cleveland Heights politics and Cain’s public life. The southern boundary of John D. Rockefeller’s estate was even closer.

Just as quickly, Cain went into politics. He later claimed that he ran for village council in 1909 because he felt the village was falling short of his ideal although since it had been in existence only eight years, he hadn’t given it much of a chance. Cain took his seat as councilman in 1910 and was elected mayor in 1914, a post he would hold until 1946.

Cain earned his living in the grain and feed shipping business, but like other village trustees, he was a player – although a relatively minor one – in the village’s booming real estate market. Banker J.W.G. Cowles, contractor J.M. Spence, and realtor William Phare were wealthier and bought and sold more property than Cain. Their activities apparently raised no questions of impropriety, and Cain’s purchase of lots on Mayfield just east of city hall was noted approvingly in the local paper. [3] These became the location of a Kroger’s, a Fisher Foods, an A and P, a Marshall Drug, and several smaller businesses and apartments, located on the second floors of the buildings in the 1920s. In 1958, he sold the properties to the city of Cleveland Heights, and they became annexes to City Hall.

During Cain’s first years as mayor, visionary developers built upscale neighborhoods along the streetcar tracks up Fairmount and Euclid Heights Boulevards: Patrick Calhoun’s Euclid Heights, B.R. Deming’s Euclid Golf, and the Van Sweringens’ Shaker Heights subdivision (now known as the Shaker Farm Historic District). Along the Cedar Road streetcar line, close to St. Ann Church, Catholic families established a beachhead in this predominantly Protestant community. Along the Mayfield street car line, developments with grand names – like Compton Heights – were laid out. They were joined by other small developments: Minor Heights, Grant Deming’s Forest Hill, and dozens of others.

Cain’s responsibilities included preserving and enhancing these neighborhoods: for example, by excluding undesirable people. In 1915, he accused Cuyahoga County of “dumping” vagrants and “professional hobos” in his suburb. Local newspapers learned that Cain could always be counted on for a pungent quote. [4]

A suburb also needed green spaces. Cain very probably was the driving force behind the Men’s Civic Club’s push for a park system. In 1915, residents passed a $100,000 bond issue to buy the land that became Cumberland and Cain Parks. Most of the land surrounded a long, steep ravine, a branch of Dugway Brook, that ran from Taylor Road to Mayfield. It would be difficult to build homes on the land, but a park would enhance the value of neighboring developments, such as Mayfield Heights. The northern end of the park was just southeast across Mayfield from Cain’s 1915 properties.

Cain and the other village trustees wanted the first park to be named “Roosevelt Park in everlasting memory of our late and beloved ex-president Theodore Roosevelt;” they also hoped it would contain a monument to him. [5] The monument never got built, and this became Cumberland Park, named for the road that constituted the park’s eastern boundary. But Cain’s choice indicated his preference for a moderately reformist Republicanism that would soon take political shape.

Cain also began his long battle to maintain suburban independence. Cleveland, its industries and commerce booming and its population growing, continued to expand its boundaries east, annexing the village of Glenville in 1905 and Collinwood in 1910. New suburban villages like Cleveland Heights, East Cleveland, and Euclid, feared they might be next. In 1915, at a symposium sponsored by the Civic League of Cleveland, Cleveland Mayor Newton D. Baker and County Commissioner Pierce D. Metzger suggested that the county government be abolished and that the “81 political subdivisions” be merged into “one mighty municipality with a highly centralized government.” The result would be more efficient and less costly governance, a refrain that would be repeated endlessly by advocates of regional government over the next decades. “Can we induce the suburban cities and villages … to lose their corporate identity for the good of the greater community?” league leaders asked. The answer was no. Cain’s response at this point was guarded: Cleveland Heights, “the decoration that adorns the plateau to the east of Cleveland,” was “not ready to come into the city until the village is completed. “[6] His position would harden over the years as Cleveland Heights grew and established its own suburban identity.

1920s: Suburban Success Story

Cleveland Heights became a city in 1921, and its suburban identity was firmly established in the next decade. Its population skyrocketed from 15,261 in 1920 to 50,945 in 1930. (Cain predicted it would reach 100,000 by 1940.) Developers built thousands of new homes in popular contemporary styles (most were casually described as “colonial”) – so many homes that the suburb was almost built out by the end of the decade. Public dollars built a handsome new city hall, a library, and built or added onto six elementary schools, two junior high schools, and a splendid high school. Thriving commercial districts sprang up along the streetcar lines at Cedar-Fairmount, Cedar-Lee, and Coventry Roads.

Cain served on the committee that drew up a new charter for Cleveland Heights. It gave the city “home rule,” which meant greater autonomy from the state and new powers to sell bonds for public projects and let contracts for public services. Reflecting current ideas about political reform, the charter provided that the chief administrator would be the city manager, chosen for his expertise, not his political connections. The mayor would be chosen by the council, not directly by the voters; all council members would be elected at large. These provisions were intended to avoid the political corruption, rancor, and inefficiency associated with urban politics.

Council also drew up a zoning code in 1921. Developers of early neighborhoods like Mayfield and Compton Heights included restrictions on land use. Yet these were dependent on the good taste and good will of developers and didn’t have the force of law. A uniform zoning code would achieve council’s goal: a suburb of primarily single-family homes, no industry, and minimal commerce, limited to main thoroughfares. (East Cleveland enacted a zoning code in 1919; Bay Village in 1920; Lakewood in 1922, and Euclid in 1923; Cleveland not until 1929.[7]) Cleveland Heights already contained many duplexes and apartment buildings and occasional commercial uses too close to residential neighborhoods, but the code would limit their expansion. So strongly did council support zoning that it voted funds to support the village of Euclid when its zoning code was challenged before the Supreme Court; Euclid v. Ambler Realty (1926) validated Euclid’s code in specific and zoning in general, which subsequently became an important tool for city planning and for directly excluding undesirable land uses and indirectly excluding undesirable residents.

Council members elected Cain mayor year after year. Like Cain, they were well-to-do –but not fabulously wealthy – businessmen and professionals like lawyer Robert F. Denison or Dr. R.E. Ruedy; most, like Cain, had held office before the new charter. They stood for business-like, efficient government, low taxes, and no public debt. So did their occasional, always unsuccessful, challengers throughout the decade. All were Republicans, as were most Cleveland Heights voters. In its endorsement of the incumbents in the 1925 council race, the Cleveland Heights Dispatch praised their “efficient and disinterested service.”[8] The Cleveland Heights Press added this ringing endorsement of Cain: “It is undoubtedly true that Mayor Cain is a sort of ringleader, a dominant figure in the council…. The re-election of Cain is especially important because he IS a LEADER …. Not only in his own community, but in metropolitan affairs.”[9]

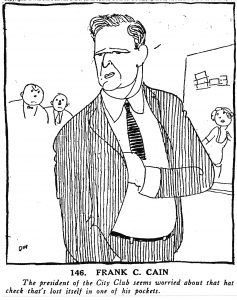

Already well known in his home town, Cain became a Cleveland celebrity. He was elected president of the City Club, making headlines for refusing to introduce invited speaker Eugene Debs, the Socialist recently released from federal prison for his opposition to the United States entrance into World War I. Cain did not, however, resign from the club after it invited Debs, as did several other members. [10] Debs declined and spoke instead at Public Auditorium. In July, Cain’s caricature appeared on the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s front page with this obscure caption: “The president of the City Club worried about that hat check that’s lost itself in one of his pockets.” [11] So well-known was he that readers apparently recognized the incident although it was not described in that or subsequent editions of the paper. In September, the paper gleefully reported that the mayor, an “irate and husky individual,” had single-handedly delivered to the Cleveland Heights police station a young man who had sped by him on Mayfield Road.[12]

Cain became the vigorous, visible spokesman for his own and other new suburbs, doing frequent battle on their behalf with the Cleveland Railway Company. “We’re out for blood,” he exclaimed in 1923, demanding that the company provide better service to the 24,000 Cleveland Heights residents who rode downtown “packed in [street]cars like cattle.”[13] He continued to push for the extension of the street car lines farther east on Mayfield, Cedar, and Fairmount and for bus lines on Lee, Taylor and Noble Roads. In 1924, Cain was chosen president of the Cleveland Metropolitan Council, composed of representatives of Cleveland and the larger suburbs to cooperate on matters of shared interest, especially transportation. In 1925, officials from Cleveland Heights, Lakewood, Cleveland, East Cleveland and other suburbs met to iron out their difficulties with the Cleveland Railway Company. All recognized that good public transportation was absolutely imperative for suburban growth. However, although Cain fumed and threatened to withhold its franchise, the company did not extend its Cleveland Heights streetcar lines until 1929.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Cain also became an outspoken advocate for suburban autonomy: “the recognized leader when, for any reason, the suburbs combined to fight the City of Cleveland … a potent enemy of proposals to limit the independence of suburban government through a metropolitan plan.” [14] His perennial foe was the Civic League. Cain shared its goal of businesslike, efficient government with low taxes. The league also endorsed city manager government, with which Cleveland experimented from 1924 to 1930. The league’s plans for regional government took various forms over the years, and supporters repeatedly reassured suburbs that a measure of regional cooperation would not cost them their independence. Nevertheless, Cain and other opponents always described these efforts as “mergers” or “annexations,” hinting at a take-over by malevolent political forces from the inner-city.

In 1925, Cain declared the league’s most recent effort at “annexation” a “dead issue.” Cleveland Heights residents were well satisfied with their municipal services, he explained. [15] A 1928 “borough plan” was even more emphatically rejected by Cain and other suburban mayors: “Our city is an ideal dwelling place for high-grade, law-abiding, respectable, decent people,” Cain claimed. “We have no Sunday picture shows. We either stop or drive out all that is bad from the city. Our city is clean, well-paved, orderly, and immensely rich.” [16] The league’s efforts, supported by the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and the League of Women Voters, persisted throughout the 1930s. Cain and other suburbs resisted.

Cain also took a vigorous stand against water rate hikes proposed by Cleveland in 1930. As president of the new Local Self-Government League, Cain called a secret meeting of the seven largest suburbs at Cleveland Heights City Hall (somehow the Cleveland Plain Dealer got wind of it). He got the credit and the blame for this organized opposition: Cain was the “organizer of the suburban bund [which] declared that Cleveland owes [his] suburb hundreds of thousands” of dollars.[17] Cain achieved a partial victory in June 1931 when the city and the suburbs reached a temporary compromise on the rate hike. The conflict raged on into the 1940s; Cain in 1940 threatened that Cleveland Heights would build its own water plant.[18]

Cleveland Heights was not only to be independent but sober and Sabbath-observant: alcohol and Sunday commerce had no place in Cain’s suburb. One of the village’s first actions had been to legislate against the spread of saloons, and most of the suburb’s property deeds prohibited the sale or manufacture of liquor on the premises. In 1931, Cain maintained that enforcing Prohibition was not a problem in his city. “We had a sensible policy,” he explained; no raiding squads, no breaking down of doors. “We just [drove out] of the city the big liquor dealers.” Nevertheless, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported a few unhappy occasions when Cleveland Heights residents broke the law. Cleveland Heights police were accused of stealing confiscated liquor in 1921.[19] In 1927, police seized a still and 15 gallons of whiskey from a home on Inglewood Road.[20]

Among the suburb’s pharmacies, bakeries, delicatessens, groceries, and clothing stores were two prospering movie theaters: the Heights (1921) and the Cedar-Lee (1926). Cain wanted them closed on Sunday – along with other commercial establishments. In April 1922, local police stopped the show at the Heights Theater, arresting the manager and two employees. “Booing and catcalls were squelched when a detail of police cleared the audience from the theater.” [21] (The arrest foreshadowed the similar fate of the same theater and the arrest of its manager, Nico Jacobellis, in 1959, on the grounds that he was showing pornography, the film “Les Amants.” He was vindicated in Jacobellis v. Ohio in 1964.) In 1931, Cain bowed to pressure from the six other council members and 9,000 petitioners, and the movie theaters opened on Sunday. The Cleveland Plain Dealer chortled, suggesting that Cain was losing his political grip. [22]

This small political loss had been more than offset by Cain’s greatest success: the largest, most ambitious residential development in Cleveland Heights history on the site of Rockefeller’s Forest Hill estate. Cain had courted Rockefeller for years, playing golf and socializing with him on his summer visits from New York City. Rockefeller sold his estate – in both East Cleveland, where his residence was actually located, and Cleveland Heights – to his son John Jr. in 1923. By the mid-1920s, the Rockefeller interests planned a $60 million residential development; it would be named Forest Hill to keep alive the memory of Cleveland Heights’ most famous almost-resident. Even better, the development “will add millions to the tax duplicate of Cleveland Heights,” frothed the Cleveland Heights Press: “Vision of Mayor Cain Responsible for Huge Project,” cried the front page headlines. [23] But these best-laid plans ran into snags. The city wanted to run Monticello Boulevard and a streetcar through the development. The Rockefeller interests balked. The Rockefeller interests wanted to build apartment houses along Lee Road; the city balked. By the time these difficulties were ironed out and the first homes were built in 1930 – in East Cleveland, not Cleveland Heights -, the Great Depression had begun. (In the post-World War II decades, the rest of the homes, the apartments, and the boulevard did get built although Monticello carried automobiles, not streetcars.]

Under Seige, 1931 – 1946

In 1928, the Cleveland Plain Dealer headlined Cain’s credo: “Cleveland Heights Mayor Believes Suburb Travels Best Alone.”[24] But traveling “alone” proved impossible during the Great Depression – even in middle-class Cleveland Heights. Residents lost jobs; the Rockefeller lots stood empty of houses, property taxes went unpaid, housing construction came to a standstill; hundreds of homes went into foreclosure. Cleveland Heights was “immensely rich” no longer.

Like other cities, Cleveland Heights initially tried to assist its own residents, establishing in April 1931, a spring clean-up project that urged residents to hire their unemployed neighbors: “Work to Do; Men to Do It.” A bond issue passed in November 1932 allowed the city to put unemployed men to work on small public works projects; in January 1933, 165 men were so employed, receiving $3.20 a day; they were allowed only two weeks’ work each month. [25] Work relief was never enough, and in any case, was available only to able-bodied men. Directed by City Manager Harry Canfield, the city supplied direct relief – food and clothing – to its own needy residents; the case work was done by Associated Charities and the Jewish Social Service Bureau. Private organizations like the Women’s Civic Club also provided food, clothing, fuel, and medical assistance to neighbors down on their luck.

Cleveland Heights became one of the last cities in the county to tighten its belt. In summer 1932, the city slashed the salaries of all employees 20 percent, including those on work relief. Cain attributed this – probably correctly – to the city’s long-standing habit of careful spending. But, he warned, “Rigid economy will be necessary” in the future.[26]

Rigid economy wasn’t enough, and in January 1933, City Council asked for $60,000 for direct relief from Cuyahoga County; Cain explained, “it’s got to the point where we do have some needy families out here who have got to be taken care of.”[27] In May, the situation was critical. According to Canfield, the city was assisting 345 families with either work or direct relief, and funds were running desperately low.[28] In February 1934, the city turned over its work relief programs to the Cuyahoga County Relief Administration and continued to assist Cleveland Heights residents who didn’t qualify for the county program.

Ultimately, federal funds provided by the Democrats’ New Deal saved this Republican suburb. Cain himself abhorred Franklin D. Roosevelt. According to his daughters, whenever the President appeared in the newsreels at the local theater, Cain “would stand up, turn his back to the screen and say in a loud voice, ‘ I don’t want to see that damn fool’” and leave the building. [29] But he and Canfield realized that partisan politics had to take a back seat to economic necessity, and with the help of U.S. Representative Chester Bolton, the city got millions of dollars from the Civil Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for dozens of street improvements like the widening and landscaping of Cedar Glen, the painting of school interiors, and parks. Especially parks.

In the depths of this Depression, Cain received his greatest honor: a park named for him. In 1934, Dr. Dina Rees Evans, the drama teacher at Cleveland Heights High, staged a production of “Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the foot of the slope at the Taylor end of the city’s first park, still un-improved and un-named. Evans wisely suggested to Cain that the park be given his name. Unemployed veterans provided by the county Soldiers and Sailors Relief Commission cleared the underbrush and culverted Dugway Brook. Cain may have paid them out of his own pocket. But much of the work was paid for by the WPA that put Cleveland Heights men to work building the theater and landscaping.

A low point for Cain: an attempted assassination in September 1938 by an angry former employee of the city’s street cleaning department, who fired three shots at him at the end of a city council meeting. Cain was safe; Canfield took the bullet; council members wrestled the assailant to the floor.

Cain’s long-time relationship with the Rockefellers paid off again in 1938 when John D. Rockefeller Jr. gave to East Cleveland and Cleveland Heights 235 acres for a public park (65 acres in Cleveland Heights), which was to encourage the development of the still vacant streets of his Forest Hill allotment. Again, the federal government came to the rescue when the WPA built the park’s scenic pathways and the splendid bridge over Forest Hill Boulevard.

As Cain clearly recognized, Cleveland Heights couldn’t survive this economic disaster without help from Washington DC. And any lingering thoughts about traveling “alone” were ended by World War II: both the mayor and his city threw themselves behind the country and the war effort.

When the United States formally declared war on December 8, 1941, Cleveland Heights residents were prepared. Many had already responded to the peacetime draft of September 1940; thousands more men and women volunteered or were drafted after Pearl Harbor. Their names – 5,832 of them, more than one of every ten residents – are inscribed on the War Memorial at the foot of Cumberland Park[30]; 191 gold stars commemorate those who didn’t come back. [31]

Women’s organizations like the Women’s Civic Club, prepared by the Depression emergency, rolled bandages and collected clothes and organized block club meetings to inform and energize neighbors to collect scrap metal, save food, and buy war stamps. Residents bought millions of dollars of war bonds. The high school organized recruitment drives; the shop classes trained defense workers. Cain Park Theater hosted a ‘Victory Sing” in August 1942. [32]

Mayor Cain also directed the city’s extensive Civil Defense activities. In July 1942, a civil defense drill involved “1,466 air wardens, 552 firemen, 74 medical aides, 23 [persons] as rescue squads, 33 at the report center, 16 regular police and 25 regular firemen.”[33] This added responsibility may explain why in 1941, he got a raise from $4800 to $6,000; council members earned $600. The state examiner forced him to return the raise. [34]

As the country approached the war, federal spending put people back to work; economic stability returned. Despite the Depression, Cleveland Heights’ population had grown almost 10 percent from 1930 to 1940, to just under 55,000, making it the 11th largest city in the state. But the Depression and then wartime shortages of manpower and materials made it difficult to maintain city services. Garbage workers struck in August 1942; Cain and Canfield refused to recognize the workers’ union and tried to ignore the strike by hiring private companies to pick up trash. In January 1945, a city worker dumped eight to ten truckloads of raw garbage into the Bluestone quarry. Neighbors complained that their calls to City Hall went unanswered. The scandal made the front pages of both the Cleveland Plain Dealer and the Heights Press. [35]

Growing dissatisfaction with the political status quo was voiced by the reliably Republican Heights Press, which had in previous years endorsed Cain and his slate of candidates. Now, week after week, the weekly pounded away at them, referring to his administration as a “dictatorship” that made all decisions behind closed doors; the council acted “like a bunch of sheep,” accommodating the mayor’s every wish while Cain himself was mostly absent from City Hall.[36] The paper even intimated that a “Second Gangland Murder” in Cleveland Heights might be blamed on Cain’s “absenteeism.”[37]

In May 1945, voters turned down a tax levy that Cain had endorsed, citing the need for expanded police and fire departments. This was one of his few political defeats. (Sunday movies in 1931 and rejection of a tax proposal in 1936 were two others). [38] Cain announced that he would not be a candidate in November. A slate of opposition candidates, backed by the Good Government League and calling for more commercial development, lost at the polls to the incumbents, Cain’s long-time fellow councilmen. Although he was not on the ballot, his policies and practices triumphed.

Cain presided over his last council meeting in January 1946, ending his 37 years in office, 25 of them as the undisputed political leader of Cleveland Heights. The Heights Press took a parting shot, accusing him of forcing city employees to contribute to the memorial stone and plaque that mark the Lee Road entrance to Cain Park.[39]

Looking Forward

After his retirement as mayor, Cain stayed almost out of the political limelight. In 1943, he had opposed a Jewish rabbinical college proposed for Patrick Calhoun’s enormous mansion on Cedar Road (now the site of Cedar Hill Baptist Church). The proposal foreshadowed two challenges the city would soon face: an influx of Jewish residents that would reshape its demographic and political make-up and the transformation of some of the suburb’s mansions into institutions that threatened the city’s residential character. In 1948, he appeared before council to oppose a proposed Veterans’ Administration hospital on Overlook Road, another incursion into another elite neighborhood. Both proposals were defeated. There is no public record of his opposition to the very controversial building of a shopping mall on the site of John L. Severance’s estate, barely a quarter of a mile from Cain’s own home. These were problems Cain left for his successors. [40]

When Cain reached his 90th birthday in 1967, Cleveland Heights had reached its peak population of almost 62,000. He accurately predicted two more challenges his city faced: the growing use of the automobile and the city’s imminent racial integration. “Suburbs like Cleveland Heights are still the best place to raise a family. Of course, the automobile changed things …. But I still don’t believe there is a necessity for more freeways like the Lee and Clark freeways.” Both proposed to cut through Cleveland Heights’ neighborhoods and parks. He continued, “As the years go by, it’s evident that whites and Negroes are getting along better. They’ll learn to live with one another eventually.”[41] It turned out to be easier to defeat the freeways than racism; the racial integration of Cain’s suburb was accompanied by occasional violence and significant social turmoil. [42]

Cain died six months later. His obituary listed his many accomplishments: the city’s charter and its strict zoning code, its public transportation, the park that bears his name, and his long fight for suburban independence. [43] Although often challenged, Cain’s vision for Cleveland Heights has mostly survived: its parks, despite the city’s financial ups and downs; the commercial and residential neighborhoods established by the zoning code (the glaring exception is Severance Town Center); the city manager plan created by the charter although it is now under study. The tradition of stubborn independence has slowly eroded: residents use the regional transportation and sewer systems; the city participates in the First Suburbs Consortium and the Northeast Ohio Public Energy Council and only recently surrendered partial control of its water department to Cleveland. But Cain would certainly recognize important things about today’s Cleveland Heights, the suburb he moved to in 1900 and worked for decades to create: its “schools, churches, and stores of all kinds,” its “FINE TREES [and]…. MANY FINE HOMES,” its “delightful surroundings [and] GOOD neighbors.”

[1] Cleveland Plain Dealer (PD), August 4, 1909: 11.

[2] PD, July 9, 1905: 20; PD, November 1, 1914: 30.

[3] PD, December 15, 1916: 22.

[4] PD, June 27, 1915: 12.

[5] Cleveland Heights Dispatch, February 3, 1919: 3.

[6] PD, February 21, 1915: 11.

[7] http://case.edu/ech/articles/z/zoning/

[8] Cleveland Heights Dispatch, October 22, 1925: 4.

[9] Cleveland Heights Press, October 6, 1925: 1.

[10] PD, January 10, 1923: 1.

[11] PD, July 2, 1923: 1.

[12] PD, September 6, 1923: 1.

[13] Cleveland Heights Dispatch, November 22, 1923: 2.

[14] PD, November 8, 1967: 47.

[15] Cleveland Heights Press, December 17, 1925: 1.

[16] PD, June 18, 1928: 9.

[17] PD, June 20, 1928: 1.

[18] PD. January 29, 1940: 4.

[19] PD, August 10, 1921: 1.

[20] PD, December 4, 1927: 1.

[21] PD, April 24, 1922: 1.

[22] PD, August 5, 1931: 10.

[23] Cleveland Heights Press, April 17, 1925: 1.

[24] PD, June 18, 1928: 9.

[25] Marian J. Morton, Cleveland Heights: The Making of an Urban Suburb (Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing 2002), 70. (Urban Suburb)

[26] PD, July 20, 1932: 11.

[27] PD, January 4, 1933: 3.

[28] PD, May 2, 1933: 12.

[29] Suzanne Ringler Jones, editor, In Our day: Cleveland Heights, Its People, Its Places, Its Past, (Cleveland Heights: Heights Community Congress, 1986), 47.

[30] PD, May 31, 1944. The number, 5,400, often used earlier by myself and others, is cited in the PD, November 15, 1943, long before the war was over when the death toll was not complete.

[31] Urban Suburb, 82.

[32] Urban Suburb, 80.

[33] Cleveland Heights Press, July 31, 1942: 1.

[34] Heights Press, July 20, 1944: 2.

[35] Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 4, 1945: 1; Heights Press, January 4, 1945: 1.

[36] Heights Press, November 9, 1944: 2.

[37] Heights Press, November 8, 1945: 3.

[38] PD, May 30, 1945: 10.

[39] Heights Press, November 20, 1945: 4.

[40] Urban Suburb, 85-122.

[41] PD, May 6, 1967: 5.

[42] Urban Suburb, 123-144.

[43] PD, November 8, 1967: 47.

Marian J. Morton is professor emeritus at John Carroll University. She received her B.A. in classics from Smith College and her M.A. and Ph.D. in American studies from Case Western University. She is the author of And Sin No More: Social Policy and Unwed Mothers in Cleveland, 1855–1990; Emma Goldman and the American Left: “Nowhere at Home”; The Terrors of Ideological Politics: Liberal Historians in a Conservative Mood; Women in Cleveland: An Illustrated History and Cleveland Heights: The Making of an Urban Suburb.