Article on James A. Garfield from the Ohio Historical Society Journal

The Rise of Warren Gamaliel Harding 1865-1920

Biography highlighting the pre presidential life of Warren G. Harding from Marion, Ohio

Written by Randolph C. Downes from The Ohio State University

The Death of Maurice Maschke

The Plain Dealer from November 20, 1936 reports the death of Maurice Maschke, Republican political boss of Cleveland for at least 2 decades.

The stories run on the front page and at least 5 other pages of the newspaper as they summarize Maschke’s life and 40-year political career.

Regional Government vs. Home Rule by Joe Frolik

(PDF version)

In the summer of 2004 a lot of the people who had labored to create Cleveland’s much-touted “comeback” in the 1990s were dismayed—if not exactly shocked—when a new Census Bureau report declared it to be America’s poorest city. Christopher Warren was no exception. Warren started out as a community organizer in Tremont long before Barack Obama gave that career path a patina of ivy league cool and long, long before the words trendy and Tremont became joined at the hip. The Tremont Warren worked in was an aging neighborhood of poor white ethnics, isolated from the rest of Cleveland by geography, crumbling roads and closed bridges.

Then in 1990, newly elected Mayor Michael R. White invited him to join his first Cabinet as Director of Community Development. After years of organizing protests against bankers, downtown developers and political power-brokers, Warren was literally at the table with them.

Then in 1990, newly elected Mayor Michael R. White invited him to join his first Cabinet as Director of Community Development. After years of organizing protests against bankers, downtown developers and political power-brokers, Warren was literally at the table with them.

The decade that followed was a heady time for White, Warren (who eventually became his economic development director) and the City of Cleveland. Blessed with a friendly Republican governor in Columbus (former Cleveland Mayor George Voinovich), a powerful member of the House Appropriations Committee in Washington (Louis B. Stokes, the brother of another former Cleveland mayor), a Democratic president who understood the importance of Ohio’s electoral votes (Bill Clinton) and a willing partner at the Cuyahoga County Board of Commissioners (Tim Hagan), White’s administration marched one big project after another across the finishing line: The Gateway complex of new homes for the Indians and Cavaliers, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and the Great Lakes Science Center, the rebirth of Tower City and a new Cleveland Browns Stadium.

But all that did not reverse decades of middle-class flight. Cleveland’s population dropped during the 1990s , as it had in every decade since 1950, to below 500,000 for the first time since 1900. Because so many of those left behind were poorly educated and lacked the skills needed in the modern workplace, Cleveland became an older and poorer city as it hollowed out. That was the snapshot taken by the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The numbers really should have been no surprise—even at the height of its “comeback,” Cleveland had been always been among the 10 poorest cities, if you were simply looking at the income of those people who actually lived within its city limits.

To Warren, part of the problem was where those limits had been drawn many decades ago. Unlike Columbus, whose seemingly elastic boundaries were a source of endless fascination and frustration to him and many of those with whom he served at City Hall, Cleveland was locked in by suburbs. It encompassed only 77 square miles—barely a third the footprint of Columbus. That meant that when a business told Warren’s economic development department that it needed more land to expand, he often had nothing to show within the city limits except brownfields that would require years of expensive, environmental clean-up. In Columbus, his counterparts would have plenty of options, including open space – greenfields, in the lexicon of development – where a business could build immediately, add payroll and start paying more taxes. Warren took great pride in one modern office park he did manage to develop – Cleveland Enterprise Park, but that was on land that the city happened to own in suburban Highland Hills.

Just imagine, Warren mused one day at lunch, if Cleveland’s boundaries were not the meandering zig-zag that appears on maps today, but squared off like those of most cities. Just imagine if the city limits stretched from the Rocky River on the west to SOM Center Road on the east and from the shores of Lake Erie south to interstate 480.

“I don’t think anybody would be talking about Cleveland as the poorest city in the country then,’’ said Warren, pointing out that neither county nor the metropolitan area had poverty rates above the national averages. “We’d look pretty good.’’

Well, thank you, Tom Johnson.

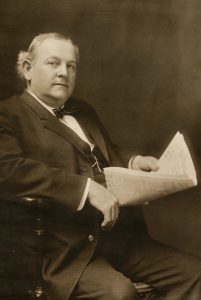

A century after he left City Hall, Tom Loftin Johnson remains the gold standard against which every Cleveland mayor—and maybe every mayor in America—is measured. Elected in 1901, after making a fortune operating private streetcar systems in Cleveland and other cities, Johnson turned Progressive movement ideals into concrete political action.

He created municipal utilities and public baths, enforced inspection standards for meat and milk, built playgrounds in crowded immigrant neighborhoods, expanded the city’s park system and convinced that city dwellers occasionally needed a dose of bucolic country life, purchased the land in far eastern Cuyahoga County on which Chris Warren would one day locate the back offices of downtown banks. He promoted Daniel Burnham’s Group Plan for public spaces and public buildings downtown. He turned City Hall into a laboratory for innovation and a showcase for how an city could and should be run. Even the great muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens declared Johnson to be “the best mayor of the best-governed city in America.’’

Oh yes. And he also pushed for Home Rule.

For the century before Johnson took office, Ohio law had constricted the power of city governments. The state had a hodge-podge approach to issuing municipal charters, which resulted in wildly inconsistent rules for what individual cities could or could not do. The state also retained the right to override local laws, giving it final say over anything that Cleveland or any other city might decide to do. It even dictated the structure of local government.

This bothered Johnson and his allies on two levels. Their Progressive ideals held that people should have as much say as possible over how they were governed. Thus the idea that officials in faraway Columbus could override the will of Clevelanders was an affront to their notions of democracy. Ohio’s cities, Plain Dealer associate editor Arthur B. Shaw would write in 1916, were “handicapped and humiliated. They were governed by a legislature controlled by rural members’’ – a complaint still heard today.

On a more practical level, Johnson and the many able people he brought to City Hall (his most notable protégés included Newton D. Baker and Dr. Harris Cooley) believed that they were more than capable of running Cleveland without the big brother of state government looking over their shoulders. When it came to the daily work city government, they wanted to be left alone. “Home rule” was the first plank in Johnson’s 1901 platform, but try as he did, he never managed to sell it to Ohio as a whole.

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced Ohio’s 1912 Constitutional Convention to add strong home rule language to the state’s newly amended governing document. It gave cities wide latitude to do almost anything that did not conflict with the general laws of the state and federal governments. With Baker stumping throughout the state, the new amendments were approved by voters that fall.

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced Ohio’s 1912 Constitutional Convention to add strong home rule language to the state’s newly amended governing document. It gave cities wide latitude to do almost anything that did not conflict with the general laws of the state and federal governments. With Baker stumping throughout the state, the new amendments were approved by voters that fall.

The victory freed Baker and his administration to do what they were already doing rather well – govern the city efficiently and innovatively. Baker became chairman of Cleveland’s first Charter Commission and helped draft a document that did away with partisan ballots or labels in municipal elections. It was swiftly ratified by city voters and Baker, initially elected as a Democrat like Johnson, served a second term before heading off to Washington as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of War.

The city he left behind was unquestionably well-governed and booming. Cleveland’s population had mushroomed from 381,000 in 1900, just before Johnson’s election, to 560,000 in 1910 on its way to 797,000 in 1920. By the end of World War I, it was the fifth-largest city in the country. Its steel mills, factories and port pulsated with energy and activity. Immigrants, especially from Eastern Europe, poured in to fill all those jobs. Entrepreneurs and inventors sprouted like weeds in a city that might fairly be called the Silicon Valley of the Industrial Age.

But all that economic and political success, says Cleveland State University urban affairs professor Norman Krumholz, helped set in motion the city’s eventual decline and some of the problems that bedevil it now in the Information Age.

As more and more people moved in to the city and the output of its factories increased, so did the unpleasant by-products of rapid urbanization and industrialization. Neighborhoods became overcrowded. Pollution darkened the skies and befouled the air.

Faced with these obvious quality of life issues, those who could afford to, moved away from the sources of irritation.

Initially, they didn’t move very far. When Cleveland was basically a walking city, only the wealthiest could afford to live even a short distance from their livelihoods—hence the “Millionaires Row” that sprouted along Euclid Avenue just east of downtown after the Civil War. But first street cars and then commuter rail systems pushed the practical boundaries of where a white-collar worker could live. “Finally, the automobile comes along and blows the place apart,’’ says Krumholz, who was Cleveland’s Planning Director under Mayors Carl B. Stokes, Ralph Perk and Dennis Kucinich. In 1900, only 50,000 Cuyahoga County residents did not live within the city limits; by 1920, that number had tripled. It would double again during the run up to the Great Depression.

But if those who might have wanted to move beyond the city limits had motive and means – and Cleveland was surely not the only big city where they did – the success of Johnson and Baker and their “home rule” triumph also provided added incentive.

Within a year of Johnson’s election, a cordon of suburbs began to tighten around Cleveland. By 1911, Linndale, Bay, Bratenahl, Brooklyn Heights, Lakewood, Cleveland Heights, Newburgh Heights, North Olmsted, North Randall, Idlewood (later University Heights), Fairview Park, Shaker Heights and Dover (later Westlake) had all incorporated as villages. For many, full city status would come by the end of the “Roaring ‘20’s.”

By contrast, when the small, lakeside village of Nottingham, at the western edge of what it now the City of Euclid, merged into Cleveland in 1912, a few years after the formerly independent communities of South Brooklyn, Glenville and Collinwood had been annexed because their residents wanted the better public services Johnson’s administration was providing, the city as it still stands a century later was essentially complete.

Charles Zettek Jr. of the Center for Governmental Research in Rochester, N.Y., has studied the proliferation of governments across America’s once booming industrial heartland from New England through the upper midwest – the Rust Belt, if you must. In city after city, as people moved away from the old urban core, they set up new governments that pretty much mirrored what they had known. The New Englanders who settled the Western Reserve brought along a tradition of autonomous villages and multiple layers of government. The European immigrants who followed had learned about turf from big-city political machines. And those moving out of Cleveland at the beginning of the 20th century had heard the Progressive gospel of “home rule” and seen the value of a well-run City Hall—though the fact that there may not have been enough Tom L. Johnsons and Newton D. Bakers to go around probably didn’t seem so obvious to them at the moment of creation.

Mixed together here, in a region where ethnic and class divisions were never too far from the surface, those ideas and experiences led to suburbanization as Balkanization. Many Cleveland suburbs essentially began as ethnic enclaves that resolutely reproduced the old cultures in which their new residents were steeped. You can see it today in the Eastern European architecture of Parma and the Tudor homes of Shaker Heights. “The whole idea was that you could control your environment’’ by using tools such as zoning that Progressives and their city planning movement had pioneered to make urban design more rational and improve the quality of life and city services, says Hunter Morrison, who followed Krumholz as planning director to Voinovich and White.

“The Vans”—brothers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, developers of Shaker Square, Shaker Heights, the Shaker Rapid line and Terminal Tower—“used home rule and zoning very explicitly as a way of differentiating the new community they were building in Shaker,’’ says Morrison. “The whole idea was that you could control your environment. You could have a nice house without the people you didn’t want as neighbors.’’ For decades, exclusionary zoning and covenants limited the presence of blacks and Jews in Shaker Heights.

Other communities may have been slightly less overt, but Morrison says the goal of incorporation was often very clearly to create an enclave for “our people.” Sometimes that was people who looked or prayed alike. Other times, the restrictions were more economic in nature. Early on, East Cleveland and Lakewood banned apartment houses. Almost everywhere the implicit message was: leave us alone.

“The impetus for zoning in Northeast Ohio was exclusion,’’ American Planning Association researcher—and Cleveland native—Stuart Meck told a City Club audience in 2002. “It was about keeping out people that we didn’t like, who lived in residences we didn’t care for, or who worshiped in a manner that made us uncomfortable.’’

The great migration of African Americans out of the South that began around the time of World War I added another layer to the distrust that came to divide Greater Cleveland. Very few suburbs welcomed blacks; most quite frankly would resist until the Civil Rights movement and the laws it produced forced them to change. But as decades passed and the city’s black population—largely segregated within Cleveland, too, thanks to race-conscious real estate agents and even federal housing programs—grew larger and more politically prominent, the urban-suburban gulf grew wider.

By the beginning of the 1960s, the sight of once solid neighborhoods in decline confirmed to many suburbanites that they had made the right decision to get out of Cleveland. Any remaining doubts vanished in 1966 and 1968 when riots, fires and gunshots ravaged Hough and Glenville, two East Side neighborhoods that had once included some of the city’s finest—and most integrated—addresses. Nuanced discussions of job discrimination, police racism and overcrowded housing had little impact on that mindset.

The nadir may have come shortly after the riots when the Stokes administration issued its “fair share” proposal for scattering public housing throughout Cuyahoga County. The lion’s share of the new units proposed by the administration—in conjunction with the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority, a nominally countywide-agency— would have been located within the city, included some in all-white West Side neighborhoods. But about a dozen units were even allocated to exclusive upper-crust Hunting Valley. It was regionalism on steroids—or perhaps, considering that it was the 1960s, on hallucinogens.

Krumholz remembers calling a meeting to discuss the proposal, inviting every suburban political leader he could think of and having no one from outside the city show up “except good old Seth Taft (the Republican county commissioner who had lost to Stokes in 1967). Everyone else answered in the newspapers.” That message from suburbia was pretty clear: over our dead bodies.

Home rule, the great goal of Cleveland’s greatest mayor, had reached it’s logical conclusion.

Those who wonder what Cleveland could have done differently to exert more control over its fate often point to Columbus. It is important to note that until the late 20th century, Columbus was a much smaller city. In 1900, Ohio’s capital had only 130,000 residents. By 1950, when Cleveland hit its peak of about 900,000 residents, Columbus had a population of 376,000. it was still largely surrounded by farmland. And that gave Maynard Edward (Jack) Sensenbrenner the opening he needed.

Sensenbrenner was a political novice who shocked the Columbus establishment when he was elected mayor in 1953. For starters, he was a Democrat, the city’s first since the height of the Depression, elected by fewer than 400 votes after one of the first municipal campaigns anywhere to make extensive use of television. Maybe his ground-breaking campaign style should have been a clue that Sensenbrenner had his eye on the future. in any case, he moved quickly to secure his city’s future.

Convinced that any city that wanted to control its destiny needed to have room to grow and the ability to manage that growth, Sensenbrenner made water his weapon of choice. The former Fuller Brush salesman decreed that any community, neighborhood or subdivision that wanted to tap into the Columbus water system or its sewers first had to agree to be annexed by the city. By the time Sensenbrenner left office in 1972—his service interrupted for four years after he lost a re-election bid in 1960—Columbus had grown from 39 square miles to 135. Today, it is more 210 square miles, sprawls into three counties and is still growing. While Cleveland is home to barely a third of Cuyahoga County residents, Columbus still accounts for two-thirds of Franklin County’s population.

Columbus’ annexation strategy certainly does not explain its economic success— being the home of two massive, essentially recession-proof jobs engines like state government and a huge public research university is a pretty nice base for any metro area, as residents of Austin and Madison can also testify. And covering so much ground clearly makes it more challenging to deliver some city services. But it also means that Columbus can offer potential residents or investors a far wider array of options than Cleveland can—and that keeps them and their tax dollars coming.

In simplest terms, says Morrison, who’s now teaching at Youngstown State University and advising Mahoning Valley leaders on how to rebuild their decimated corner of Ohio, “The energy (of development) goes to the new”—and when a business or a developer wants to build something new in Central Ohio, Columbus has room for them to do it. Without space to grow, adds Krumholz, even the most innovative mayors hit a brick wall: “As your population goes down and your housing ages, you want, you need, to redevelop, to rebuild your aging infrastructure. But you can’t because your tax base is going down, too.’’

Could Cleveland have done what Columbus did and essentially forced its suburbs back into the fold of what former Mayor Jane Campbell used to call the “mother city?” After all, Cleveland’s Division of Water provides water to most of Cuyahoga County as well parts of several adjacent counties.

In theory, the answer is yes. But the reality is that Cleveland’s leaders faced their moment of decision much earlier than Columbus and Sensenbrenner did. Based on the view from their City Hall, Cleveland’s leaders—including the sainted Johnson and Baker, who were in charge when the suburban fence around the city began rising—chose to see water as a commodity to be sold, a profit center that enabled them to serve their own citizens better. To them, more suburbs meant more customers. Keep in mind that Cleveland in those days wasn’t built out either. There were still vast tracts of vacant land within its city limits; much of what are now the West Park and Lee-Harvard neighborhoods were not developed until after World War II. And almost no one in pre-war America could have anticipated the emergence or the impact of the freeway which allowed Greater Cleveland to sprawl east, west and south—while Cleveland’s 77 square miles could not change.

Only lately, at the beginning of the 21st century, have Cleveland leaders began to think of ways to leverage the fact that their water system is in fact a regional asset. Campbell established a joint development district in Summit County, agreeing to supply water to a new office park in Richfield in return for a share of tax dollars generated there. Her successor, Frank Jackson, struck a major blow for regional thinking when he offered to assume the cost maintaining water lines in any community that agreed not to “poach’’ employers from other cities in the region by using tax abatements or other incentives. Some suburbs, especially those in the “inner-ring” around Cleveland, quickly signed on. But some of the most affluent cities have been slow to come the party.

Their reluctance underscores a long-standing problem of Cleveland and many other older cities. it’s one thing to talk about regionalism, it’s another to live it.

Look at it this way: advocates of regionalism—a frankly mushy term that can mean everything from support for Indianapolis-style unigov to a vague sense that economically, at least, this is a single labor market—love to point out that when people from Greater Cleveland travel and someone asks where they’re from, they generally say “Cleveland.”

And on many levels, that’s true. We all root for the Cleveland Indians, the Cleveland Browns and the Cleveland Cavaliers. Our children take field trips to the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo and the Cleveland Museum of Art. We impress visitors by taking them to the Cleveland Orchestra and the Cleveland Air Show. When a LeBron James disses Cleveland, the pain extends far beyond even the borders that might exist in Chris Warren’s wildest dreams.

The problem, of course, is that when those same travelers get home and someone asks where they’re from, the answer is likely to be some very specific community. In Cuyahoga County alone, there are 58 other municipalities besides Cleveland to choose from. Add in school districts and special taxing districts and there are about 100 units of government in Cuyahoga County. Zettek and Bruce Katz, who studies urban issues for the center-left Brookings Institute think tank, say that’s actually fairly common for older industrial areas.

But many of the subdivisions that might have made sense in the go-go days of the early 20th century are almost impossible to justify in the more challenging landscape of the 21st.

Researchers hired by The Fund For Our Economic Future—a foundation-driven consortium that is trying to jumpstart development in Northeast Ohio—have identified the “legacy cost” of excess government as a drag on this region’s growth because it adds to the bottom-line of doing almost everything. In follow-up work commissioned by the fund, Zettek concluded that when all governments are accounted for, Cuyahoga County spends almost $800 million a year more than Franklin County. Think of that as the cost of home rule run amok.

So, what now? The fund has begun offering prizes to communities that come up with the most promising plans for collaboration. The fact that some of the early finalists have been as mundane as a shared maintenance garage for one suburban city and its school district shows how far the discussion has to go. many of the candidates for Cuyahoga County’s new chief executive and council promise to encourage policy cooperation, joint buying and shared services. A few brave souls even suggest that the new, streamlined county structure could eventually lead the way to a single metropolitan government.. However they come down on that grand question, almost everyone who thinks about the future of this area says we simply can’t do business as usual.

Bruce Akers could n’t agree more. Akers was at Cleveland City Hall almost a generation before Warren—now Mayor Frank Jackson’s regional economic development czar— arrived. He was Ralph Perk’s chief of staff in the 1970s. Eventually, he became mayor of Pepper Pike, a bedroom community that in 1924 was carved out what was once Orange Township. As a leader of the Cuyahoga County Mayors and Managers Association, Akers has spent more than a decade trying to convince other suburban officials that they need a new model of cooperation—one premised on two central ideas: one, that every community in Greater Cleveland will sink or swim together. And two, that Cleveland’s fate will dictate everyone else’s. That’s led Akers to embrace Hudson mayor Bill Currin’s call for regional tax sharing.

n’t agree more. Akers was at Cleveland City Hall almost a generation before Warren—now Mayor Frank Jackson’s regional economic development czar— arrived. He was Ralph Perk’s chief of staff in the 1970s. Eventually, he became mayor of Pepper Pike, a bedroom community that in 1924 was carved out what was once Orange Township. As a leader of the Cuyahoga County Mayors and Managers Association, Akers has spent more than a decade trying to convince other suburban officials that they need a new model of cooperation—one premised on two central ideas: one, that every community in Greater Cleveland will sink or swim together. And two, that Cleveland’s fate will dictate everyone else’s. That’s led Akers to embrace Hudson mayor Bill Currin’s call for regional tax sharing.

He understands what a tough sell that will be. But he thinks Northeast Ohio has no choice but to change. Instead of pulling apart, he says, it’s time to pull together. Akers notes that now some of his neighbors have become more interested in the collaborations he’s been pushing for years. The dismembered pieces of Orange Township—Pepper Pike, Orange, Woodmere, Hunting Valley and Moreland Hills—already share a school system and recreation center. Now even these mostly affluent communities have begun to realize they can’t afford to stand alone in other civic enterprises.

“I think someday we’ll see those five communities back together,” Akers says. “Sheer necessity is going to force us to think that way.’’

Tom Johnson also saw home rule as a matter of sheer necessity. To make Cleveland great in the new 20th century, it needed the power to stand alone. Perhaps one key to its revival in the 21st century will be enough communities surrendering that power—in hopes of finding even more by standing together.

Marcus Alonzo Hanna: his life and work By Herbert David Croly

Famous (in its day) biography of Marcus Hanna, who died in 1904. Written in 1912

Collinwood Fire Memorial Book

From the Cleveland Public Library

The Correspondence of George A. Myers and James Ford Rhodes, 1910-1923

Article from The Ohio Historical Society

Mr. Ohio

From the Columbus Dispatch, December 12, 2010

Mr. Ohio

George V. Voinovich’s dedication to faith, family and state set the foundation for his unprecedented 43-year run in public office, including as a mayor, governor and senatorSUNDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2010 03:02 AM

|

Water by Brent Larkin

Water As An Economic Tool (PDF)

By Brent Larkin

Northeast Ohio should regard building a vibrant water-based economy as a priority so important that the future of the entire region depends on it. It probably does.

Water isn’t the only key to a prosperous future. World-class medical facilities, biosciences, renewable and alternative energy all show promise of contributing to our 21st- century economy. But the unquestioned key to that future is an asset whose origin dates back more than a billion years—the world’s most abundant supply of fresh water.

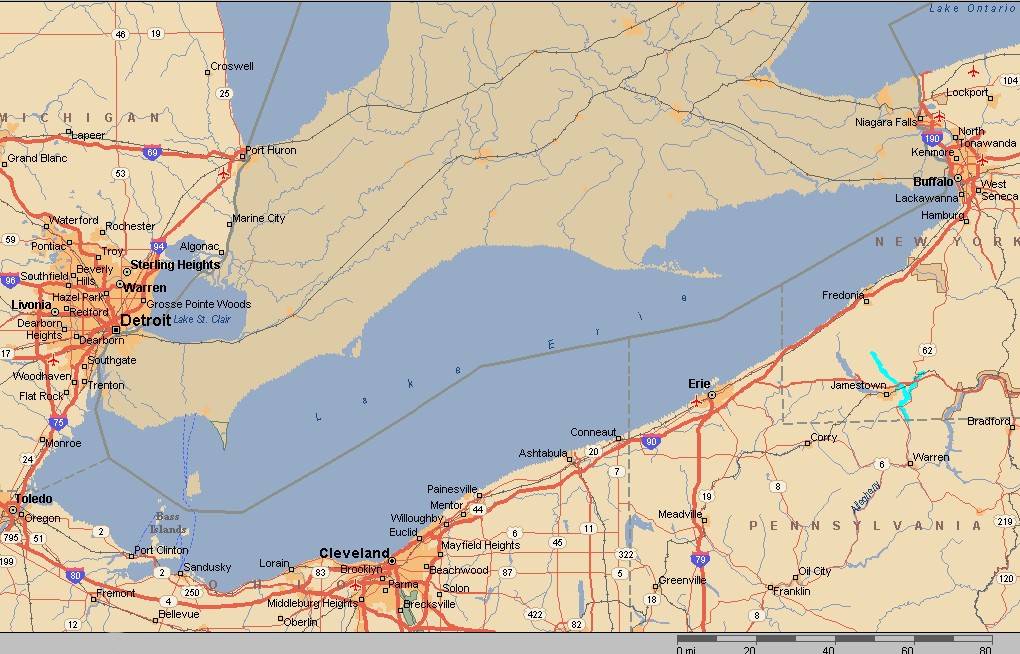

Of all the world’s water, 97 percent of it is salty. Another 2 percent is locked in ice or snow. Of that remaining 1 percent that is fresh water, the Great Lakes contain just under 20 percent of it. Lakes Erie, Ontario, Michigan, Huron, and Superior boast a total of 11,000 miles of shoreline. Recreation alone on the lakes is a $6 billion-a-year industry.

In considering the magnitude of the importance of Northeast Ohio’s most precious asset, consider that 46 percent of the world’s population does not have water piped into their home, that in undeveloped countries people must walk an average of 3.7 miles to get fresh water.

We have 6 quadrillion gallons (that’s 15 zeros) of it at our doorstep.

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.

Manufacturing will remain a significant part of Northeast Ohio’s economy for the foreseeable future, but it’s decline as the centerpiece of that economy has been inexorable and—when viewed with the benefit of hindsight—inevitable.

But booming economies in the West, Southwest and Southeast are now running out of the water they so desperately need to sustain their growth. Indeed, some aquifers in California are down to 25 percent of

capacity.

So as other parts of the country—and world—dry up, cities with great quantities of clean, fresh water have the potential to enjoy an economic resurgence. By 2025, an estimated one-third of the world’s population will not have access to fresh water. As a 2008 Goldman Sachs report concluded, fresh water has become “the natural resource with no substitute.” but as Northeast Ohio plans a water-based economy, that planning requires an understanding and appreciation of history. So before explaining how water can return the region to prosperity, let’s examine its paramount role in the greatness of our past.

In 1772 and again in 1786, a missionary and geographer named John Heckewelder visited the Indian-occupied territory along the Lake Erie shoreline at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. Heckewelder was captivated by the location, which featured the vast lake and countless streams feeding into the river. It was, he thought, the ideal place for a settlement as the young nation expanded west.

On his second visit, Heckewelder established a small trading post along the Cuyahoga, close to what is now known as Tinkers Creek. He also prepared a map of the region.

Relying in part on that map, in 1796 a group of eastern investors purchased from the state of Connecticut what is now the Greater Cleveland region, paying $1.2 million for about three million acres (a little more than 30 cents an acre). They named it the territory of the Western Reserve.

In May of 1796, investors in the Connecticut Land Co. designated Moses Cleaveland as their agent to visit the territory. On July 4, 1796, Cleaveland and his sailing party of about 50 men reached Conneaut. About two weeks later, the group mistakenly thought they had reached its final destination, disappointing surveyors at the small size of the river.

So unhappy was Cleaveland’s group that legend has it they named the small river the Chagrin. More likely is the Indians had already given the Chagrin its name.

Having discovered its likely error, Cleaveland’s party continued west, and on the morning of July 22, 1796, slipped into the Cuyahoga and embarked near the area of the Flats east bank, now known as Settlers Landing. On the day the Cleaveland party landed, the east bank of the Cuyahoga represented the most western point in the United States, or its territories, not controlled by Indian tribes.

Cleaveland was exhausted, but wrote that the location—with its crystal clear lake, magnificent rivers, rich forests, fertile soil, and rolling hills—exceeded investors’ expectations. Within days, Cleaveland had struck a deal with the Iroquois to plot a village east of the river, just south of Lake Erie.

Three months after arriving, Cleaveland left the city that now bears his name, absent that first “a.” He never returned.

In the late 18th century, both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were known to ponder ways of moving goods from the west (the area now known as the Midwest) to population centers in the east. Both centered on the idea of a canal that would move products east along the Ohio River, and at one point Washington was said to recommend a canal that would connect the Ohio to Lake Erie, alongside the Cuyahoga River.

Absent access to a market, farmers in and around the new village of Cleveland struggled in the town’s early years. Then, in the early 1820s, Ohio’s leaders concluded the only way to ensure economic prosperity for the entire state was to construct a canal from the Ohio river north, through Columbus, to Lake Erie.

Many thought the canal’s northern terminus should be in Warren or Sandusky. Alfred Kelley believed that terminus should be in Cleveland. And Alfred Kelley turned out to be a very persuasive man. A lawyer, county prosecutor, the youngest elected member of the legislature, and the first president (1815) of the village of Cleveland, Kelley became the state’s most outspoken and effective promoter of the Ohio & Erie Canal.

In 1821, the state legislature began deliberating issues relating to the canal’s funding, route and construction. Kelley’s relentless lobbying paid off, and in 1825 ground was broken on the northern section of the canal that would link Akron to Cleveland. On July 4, 1827, the first boat to travel the canal route from Akron arrived in the Cleveland Harbor.

By the early 1830s, construction on the canal was complete. Economic growth was now all but guaranteed. And Alfred Kelley had earned his place as one of Cleveland’s greatest citizens.

Consider the canal’s economic impact: In 1830, about three million pounds of goods traveled the canal. By 1838, that number had grown to nineteen million. Products from central Ohio’s farmlands poured into Cleveland’s port, filling the harbor with steamboats and other vessels awaiting their turns at the dock. The dramatic increase in business at the port sparked a building boom along the river and on Superior Avenue, as schools, churches, warehouses, and office space gave birth to what was becoming one of the most vibrant and successful ports on the Great Lakes.

Cleveland could offer something unique, direct access east to New York or southeast to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. No other city on the Great Lakes had water access to New York or New Orleans.

Water was pushing this new young village on a path to prosperity.

In the summer of 1860, the Cleveland Leader, one of the city’s daily newspapers, complained of the city’s plight, “We continue to make nothing and buy everything.” That was about to change. Railroads had dramatically reduced the importance of the Ohio & Erie Canal. By the start of the Civil War, five major rail lines passed through the city. At war’s end, iron from the Lake Superior region began arriving by lake carriers in record amounts.

Much was then shipped by rail to steel manufacturers in Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Youngstown. But by 1868, Cleveland itself was home to more than a dozen steel rolling mills. As the industrial revolution generated startling economic growth across the country, for a time no city grew faster than Cleveland. Water and rail made Cleveland a manufacturing giant, the country’s second largest automotive city, and the largest shipbuilding port on the Great Lakes.

Cleveland’s water-based economy was huge, diverse, and—as the 20th century arrived—seemingly recession-proof. In 1860, Cleveland was a relatively tiny town of 43,000. Seventy years later, it was home to a world-class port and a population of more than 900,000—the nation’s sixth largest. Access to water had made it a vibrant and prosperous city. but the end of that prosperity—and the city’s wise use of its water was nearing the end.

Cyrus Eaton, Cleveland’s world-renowned industrialist, once said the Depression hit his hometown harder than any city in the country.

Indeed, the loss of jobs and the post-war flight to the suburbs launched Cleveland on a path of slow, albeit relentless, economic decline.

As the city began to lose residents and jobs, Cleveland also paid a price for not tending to its greatest asset. By the 1960s, both Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River became dangerously polluted, significantly damaging the Northeast Ohio fishing industry and dealing a crippling blow to the city’s reputation.

On June 22, 1969, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga caught fire. Flames on the river reached five stories high. Wooden bridges burned. The city’s water, the primary source of its greatness, made it the butt of jokes that linger to this day.

Three things must happen with our fresh water is it is to play a pivotal role in northeast Ohio’s economic recovery. We must: 1. keep that water here. 2. keep it clean. 3. rebuild the port as an economic hub.

For decades, Lake Erie and the river suffered as phosphorous and other industrial pollutants poured into the water unchecked, killing fish and other helpful species, giving the water an untenable odor, closing beaches, and spreading contamination north to the Canadian shoreline.

In 1972, Congress finally acted, passing the Clean Water Act, which regulates the discharge of pollutants into the nation’s surface waters, including lakes, rivers, streams, wetlands, and coastal areas. The act dramatically curtailed the discharge of untreated waste water and sewage from government and industrial sources, and eventually made both Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River safer for swimming and fishing.

The results were remarkable. But eventually, problems returned. Lake Erie today again faces significant problems—largely invasive species, sediment, and the vestiges of pollution. The lake and the river are back from the dead, positioned to play a vital role in the 21st-century economy. But it is worth restating that this rebirth will be sustained only if we keep our water clean, wisely build an economy around it, and prevent other parts of the country from tapping into what is Greater Cleveland’s most precious resource.

Toward that end, in 1986 Congress passed the Water Resource Development Act designed, in part, to prevent diversion of Great Lakes water. But many legal scholars thought the act vulnerable to a legal challenge, so in the mid-1990s representatives of the eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian provinces began negotiating a basin-wide approach to decisions on water usage.

The result was the St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact—commonly called the Great Lakes Compact, a product of more than four years of negotiations by the governors, a 39-member advisory committee, and input from thousands of U.S. and Canadian citizens. Canada enacted the compact rather quickly. Approval by the eight states and the congress took more than five years.

The Ohio House twice ratified the compact, the second time by a vote of 90–3. But Ohio was one of the last states to give its final approval because the compact stalled in the Ohio Senate for more than a year. an April 27, 2008, editorial in the Cleveland Plain Dealer—one of many the newspaper wrote urging Ohio to ratify the agreement—angrily suggested the Senate’s foot-dragging “represents one of the most unforgivable public policy abuses perpetrated upon the people of Northeast Ohio in decades.” The paper accused more than several senators of concocting “some crackpot theory” that exposed “all of Ohio to economic harm.”

After allowing some face-saving for the Senate, Ohio became the sixth state to ratify the compact. In October of 2008, President George W. Bush signed it, just days after its approval by the U.S. House and less than a month after passing the U.S. Senate.

Now the law of the land, the Great Lakes Compact essentially bans diversion of large amounts of water outside the Great Lakes. In the United States, each of the eight Great Lakes states has a seat on a water resources council. Any water withdrawal exceeding five million gallons daily must be approved by a majority of the council. Similar diversion rules apply in Canada. In Ohio, only counties straddling the Great Lakes Basin are allowed to use Lake Erie water. Diversion approved prior to the compact’s ratification, like Akron’s large scale use of Lake Erie water, are allowed to continue.

The importance of preventing diversions is enormous, as public officials in arid parts of the country have been publicly talking of preying on Great Lakes water since the early days of the 21st century. In late 2007, when he was running for president, new Mexico Governor Bill Richardson called for a national policy to consider redistribution of water to needy areas, remarking that the West was drying up while places around the Great Lakes were “awash in water.” It was around then that a professor at the University of Alabama produced a plan to pipe water out of the Great Lakes into the Sunbelt.

David Naftzger, a former director of the Council of Great Lakes Governors, predicted in 2008 that an eventual water grab is a certainty. “Look at a map showing water shortages and population growth and see how they match up,” Naftzger told the Plain Dealer. “Now look at us and you can see a concern that, as times move on, those areas will be looking at the Great Lakes to bring them water— through either a tanker, pipeline, or natural channels.”

While Congress has the power to repeal the Great Lakes Compact, for now the world’s largest supply of fresh water appears safe. But as a great many commentators have observed, while 20th-century wars were often fought over oil, 21st-century wars will be waged over fresh water.

But even under a worst-case scenario, if some Great Lakes water ends up being diverted later in the century, the advantages enjoyed by the bountiful supply of fresh water enjoyed by just 8 of the 50 states argue strongly for future economic growth.

President Barack Obama has championed a proposal, as of this writing not yet law, that would spend an additional $5 billion over a 10-year period to continue Great Lakes cleanup as part of a plan to revive the lakes’ economic, recreation, and navigational potential. A 2008 Brookings Institute report concluded that such a cleanup would provide Cleveland with an economic boost between $2.1 billion and $3.7 billion with the overall economic benefit to the Great Lakes states estimated at a staggering $100 billion.

The logic is irrefutable. A cleaner Lake Erie for fishing, boating, swimming, and other water activities would not only drive up property values, but would also make the region more desirable for businesses creating jobs and generating wealth. As Greater Cleveland Partnership President, Joe Roman correctly noted, “With 300 miles of shoreline, Cleveland and the rest of Northern Ohio could thrive if we are able to fully realize the economic potential of this tremendous asset.”

Officials in Wisconsin figured this out years before it occurred to those in Greater Cleveland. Four of the world’s 11 largest water technology companies are located in Wisconsin. Milwaukee alone is home to 120 water-related companies. Marquette University Law School now has a water-law curriculum. And planning is underway for a $30 million lake-front headquarters of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Great Lakes Water Institute. Board members and leaders at the Great Lakes Science Center are now engaging in similar water technology efforts, but no one disputes that Greater Cleveland lags behind Milwaukee in planning for a water-based economy of the future.

Toledo Blade

Another significant problem is the troubling growth of toxic algae in Lake Erie and the spread of zebra mussels. The algae colors the water green and can be dangerous to humans, pets, and wildlife. Zebra mussels harm the fishing industry and pollute beaches. These festering problems only underscore the importance of a sizable, federally-funded Great Lakes cleanup plan.

Rebuilding Cleveland’s port as a significant shipping center is proving an even more daunting challenge. the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port authority, a vision of former Mayor Carl Stokes and Council President James Stanton, was created by county voters in 1968 to oversee what was then one of the Great Lakes’ busiest ports. For the first few decades of its existence, the port thrived. For decades, shipping raw materials to make steel was the port’s main business. But even with the steel industry’s decline, an economic impact study in the late 1990s found the port directly accounted for 4,700 jobs, generated $400 million in spending annually, and $64 million in taxes.

But the port also engaged in a obscene amount of over-ambitious thinking, devoting an inordinate amount of time on plans for a World Trade Center, cruise ship and ferry service, an aquarium and lake front retail none of which materialized. Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, shipping at the port declined steadily.

With shipping revenues in a free-fall, the port has struggled to raise its $158 million share of the $600 million tab the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers needs to dredge mountains of muck from the port and Cuyahoga River. Without that dredging—and a place to dump the muck, federal officials have warned that the Cleveland harbor could be shut down by 2015.

By the summer of 2010, Cleveland’s port was in clear crisis mode. the nine-member board fired its director and hired a new one. it scrapped a costly, $1 billion plan to build a new port several miles east of downtown. there was no clear game plan to raise the funds needed for dredging, nor one to revive its slumping shipping business. adding to those woes was the city’s need to secure federal funding to fix a crumbling slope above the river that threatened shipping to sites downstream.

In a series of news stories and editorials, The Plain Dealer outlined the port’s many “immense challenges,” underscored the need for dramatic change, and correctly linked the need for that change with the necessity of the port playing a major role in reviving Greater Cleveland’s economy.

An old, now somewhat trite, saying holds that, in determining the success of a business, the three most important factors are always location, location, and location. The visionary pioneers who settled this territory more than 200 years ago understood that.

Northeast Ohio and, indeed, the entire Great Lakes region, has something the rest of the world desperately needs. What’s more, we have a lot of it.

More than ever before, the fresh water that served us so well in the past represents our best hope for the future.

Bibliography

archives, The Atlantic “Water Summit.” October 29, 2009.

archives, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. 2009.

archives, The Plain Dealer. 1991–2010.

Miller, Carol Poh and Robert Wheeler. Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796–1996. 2nd edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Rose, William Ganson. Cleveland: The Making of a City. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1950. reprinted with a new introduction. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1990.

Van Tassel, David D. and John J. Grabowski. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. 2nd edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Wallen, James. Cleveland’s Golden Story: A Chronicle of Hearts that Hoped, Minds that Planned and Hands that Toiled, to Make a City “Great and Glorious.” Cleveland: William Taylor & Son, 1920.

Water: Our Thirsty World. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, April 2010.

Further resources: http://www.great-lakes.net/teach/about/

Colorful Kohler Checkered Past Doesn’t Stop Oddball From Getting Elected

Sunday July 5, 1998 Plain Dealer article about Fred Kohler

COLORFUL KOHER CHECKERED PAST DOESN’T STOP ODDBALL FROM GETTING ELECTED

– FRED KOHLER –

Fred Kohler was Cleveland’s most colorful mayor – and the colors were orange and black. They showed up on park benches, waste baskets, city buildings, hydrants and especially signs like the one above.

But even without paint, nobody was as colorful as Kohler. In 1910, Theodore Roosevelt called him “the best police chief in the United States.” He was fired in disgrace for “gross immorality” in 1913, and defeated by voters in 1913, 1914, 1915 and 1916.

Then, in 1921, he was elected mayor in what The Plain Dealer called “the most bizarre and dramatic mayoralty fight Cleveland has ever witnessed” – one in which he was opposed by Democrats, Republicans, newspapers, ministers and civic organizations. And one in which he had no organization, no campaign funds and made no speeches and no promises.

Fred Kohler dropped out of school in the sixth grade to work in his father’s business. In 1889, at the age of 25, he achieved his boyhood dream of becoming a police officer. He rose quickly through the ranks and in 1903 was named chief by Democratic Mayor Tom L. Johnson, even though Kohler himself was a Republican.

He built a national reputation as a spit-and-polish chief who wielded an ax on vice raids while adopting a “golden rule” policy in which first-time minor offenders were released with a warning. He put houses of prostitution out of business by stationing an officer at the door to take the names and addresses of their customers.

In 1910, Mayor Herman Baehr tried to fire Kohler on 25 charges of drunkenness, immorality and conduct unbecoming a police officer, but the Civil Service Commission exonerated him. He was not as fortunate in 1913, after a citizen returned home to find the police chief in bed with his wife. There was a messy divorce and ministers demanded Kohler’s dismissal.

This time, the Civil Service Commission fired him. “All right, boys,” Kohler told reporters. “I’ll be leading the Police Department down Euclid Ave. again someday.”

He promptly ran for councilman in his home ward. To everyone’s surprise, he finished first in first-place votes but lost when second- and third-place votes were counted.

Undaunted, he ran for sheriff the next year and lost. Then he ran for clerk of Municipal Court and lost. Then he ran for county commissioner and won the Republican nomination but lost the general election. In 1918, however, he was elected county commissioner – the only Republican to win that year – and in 1920, led all vote-getters in winning a second term.

That made Kohler a contender for mayor. Still, nobody gave him a chance in the seven-candidate field, especially since he shunned all public appearances. Instead, he trod the streets for months, ringing doorbells and telling citizens, “Hello, I’m Kohler. I’m running for mayor. If you vote for me, I’ll appreciate it. If you don’t, I’ll never know and we can still be good friends just the same.”

Kohler amazed the experts by finishing first, 2,500 votes ahead of Mayor William Fitzgerald. He amazed them again by naming a highly qualified Cabinet without even asking his appointees whether they had voted for him. His first order to them: Prepare a list of unnecessary city workers.

Before the month was out, he had fired 400 employees, cut the pay of the rest by 10 percent, forced them to punch time clocks and notified city unions that existing labor agreements would not be renewed. When the unions threatened a general strike, Kohler said the city would close down if it had to. Critics tried to recall him, but failed to collect the 15,000 signatures to put the issue on the ballot.

Anticipating Dennis Kucinich by 65 years, he called a council investigation “a bunch of pinheads seeking cheap publicity.” At the dedication of Public Hall, he denounced “uplifters” (the do-gooders of that era) who got in the way of “practical roughnecks” like himself. Three of his directors resigned after run-ins.

He rejected plans to buy new guns for police, telling them instead to keep the old ones clean. He put signs in city elevators: “Please keep your hats on so that you may have better service.”

But he also stepped up paving, cut streetcar fares, put up street signs, made police shine their shoes, bought an elephant for the zoo, ordered cleanups of city property and told employees they would not be forced to contribute to the Community Fund. And he kept citizens informed of his accomplishments with orange-and-black signs such as, “Tax and Rent Payers have received a dollar’s worth of value for every dollar spent – FRED KOHLER , MAYOR.”

At the end of his term, Kohler declared he had saved taxpayers $1.8 million. Nobody knows whether he would have been re-elected – the city manager plan took effect at the beginning of 1924 – but he won two terms as county sheriff after leaving City Hall. The second ended in turmoil when he was reprimanded for skimping on prisoners’ food and using the money thus saved for other purposes instead of returning it to the county.

Years later, he reflected on his career: “Yes, sir, I wouldn’t mind going all over it again, because I know I was right. And if I did, I’d tell all the old crowd to go to hell – newspapers, council, uplifters, tipoff guys, political hangers-on, bookbugs, ingrates – the whole crowd. I’d paint everything orange again.

“I know I’ve been accused of being high-handed, but I was elected mayor, not anybody else. It was my picnic or my funeral.”