The history of the Cleveland Public Library written by C.H. Cramer in 1972

The full book is online courtesy of the Cleveland Public Libary

The chapter about Linda Eastman starts on page 138

www.teachingcleveland.org

The history of the Cleveland Public Library written by C.H. Cramer in 1972

The full book is online courtesy of the Cleveland Public Libary

The chapter about Linda Eastman starts on page 138

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The link is here

EASTMAN, LINDA ANNE (17 July 1867-5 Apr. 1963), the fourth librarian of the CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY, succeeding her friend and mentor WM. HOWARD BRETT†, was the first woman in the world to head a library of that size. Eastman was born in Oberlin, Ohio, daughter of William Harley and Sarah Ann (Redrup) Eastman. Her family moved to Cleveland when she was 7 and Eastman attended public school, graduating with honors from West High. Completing a course at Cleveland Normal School, Eastman began teaching but soon found herself attracted to library work. She became an assistant at the CPL in 1892 and was promoted to vice-librarian under Brett in 1895. Eastman was named librarian in 1918, a position she held until her retirement 20 years later. Her first years were dominated by the construction and occupancy of the $4.5 million main library building, opened in 1925. Later in her tenure, she developed several specialized operations, including a travel section, a business information bureau, and services to the blind and handicapped. Eastman’s achievements within her profession were highly regarded and recognized nationally. She was president of both the Ohio Library Assoc. and the American Library Assoc. and held a professorship at the Library School of Western Reserve University. She retired as librarian in 1938, when she was 71. Eastman died in CLEVELAND HEIGHTS and was buried in RIVERSIDE CEMETERY.

Article about Margaret Bourke-White written by Patrick Cox, Ph.D

| Margaret Bourke-White History Making Photojournalist and Social Activist January 2003 |

|

In the beginning, there was Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971). One of the trailblazers in twentieth century photojournalism, Bourke-White played an historic role in media and women’s history. As a woman photojournalist, her reputation rivaled Ida Tarbell, the muckraker who exposed the abuses of Standard Oil, in its impact on modern journalism. Bourke-White became an internationally famous photographer and holds many “firsts” in her portfolio. In addition to her professional contributions, her activism on behalf of the poor and underprivileged throughout the world places her among the foremost humanitarians of the century.

When Bourke-White entered the field of journalism in the 1920’s, few women participated as professional journalists or photographers. A handful of women photographers, Frances Benjamin Johnson, Jessie Tarbox Beals and a few others represented an earlier generation whose photos appeared in newspapers and magazines in the early twentieth century. Although social and vocational roles expanded in the 1920’s, women lived in an era of rigid expectations. Female journalists remained mostly confined to the women’s and society pages of the metropolitan newspapers. As more women entered the profession in the 1920’s and 1930’s, a few doors began to open for women to assume the tasks traditionally taken by male reporters and photographers. Margaret Bourke-White rushed through this door to become a leading figure in the profession.

With the encouragement and guidance of her father, Bourke-White began taking photographs at an early age. She completed college at Cornell and opened her own photographic studio in Cleveland. She ventured into the fiery steel plants where women never ventured. The fiery cauldrons, molten steel, and showers of sparks depicted the industrial might of the nation. The dynamic series of industrial photos in the 1920’s caught the attention of Henry Luce. The well-known publisher hired Bourke-White as the first photographer at Fortune magazine in 1929. Her first assignment in the premier issue provided a physical and a professional challenge – covering the Swift hog processing plant – a site as challenging as the steel mills with its pungent air, bloody working conditions and where one misstep could prove fatal. She went to Russia and provided the first extensive photo series on Soviet Union. Dams, factories, farms, workers, farmers and every day life in Stalin’s communist state came to life for the first time to viewers in the west.

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.

During this period Bourke-White teamed with the popular southern novelist Erskine Caldwell. One of the most widely read authors of the twentieth century, Caldwell is best known for his works God’s Little Acre and Tobacco Road. Working in the poverty-stricken rural areas of the American South, the dynamic team published You Have Seen Their Faces. The pictures of poverty and discrimination in the south rivaled the urban privation photos of Jacob Riis. The gaunt faces revealed the abysmal social and economic conditions of the Depression-era south. Their work received acclaim but was criticized for its bias and exposure of racism in the south. Years after their automobile tour of the south, Caldwell lauded Bourke-White. “She was in charge of everything, manipulating people and telling them where to sit and were to look and what not. She was very adept at being able to direct people,” he said in an interview. Bourke-White and Caldwell were the only journalists in the Soviet Union when the German Army invaded in the summer of 1941. The couple married in 1939 but their relationship ended during World War II.

During World War II, Bourke-White became one of a stalwart group of women correspondents who covered the war from the front lines. Her book They Called It Purple Heart Valley provided a narrative and photographic study of the war in Europe in 1944. She took photos of foot soldiers and generals, victims of the war and its destruction. She slogged through the mud and heat and went everywhere from the front lines to the hospital wards. As she accompanied troops in the Italian campaign, Bourke-White wrote of one encounter. “Right beneath my feet, at the foot of the cliff, was a row of howitzers sending out sporadic darts of flame. Since I was so high up and so far forward, most of our heavies were in back of me, and I could look over the hills from which we had come and see the muzzle flashes of friendly guns, looking as if people were lighting cigarettes all over the landscape.”

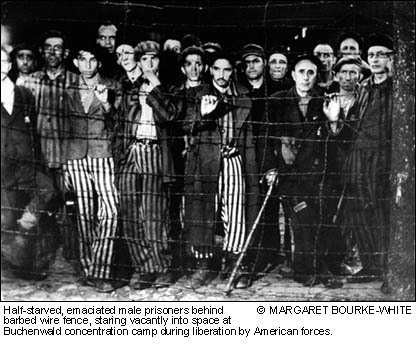

In one of her most difficult tasks, Bourke-White accompanied U.S. troops as they liberated the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1945. With portraits of starving prisoners and dead bodies heaped one upon another, she documented some of the worst horrors of the Nazi regime. Even with government censorship, Bourke-White and her fellow photographers and journalists gave Americans an unprecedented view of the global conflict and the human suffering the war created.

© Patrick Cox, Ph.D

Assistant Director, Center for American History

University of Texas at Austin

pcox@mail.utexas.edu

Dr. Cox authored the biography on the late U.S. Senator Ralph W. Yarborough (D-Texas) published by the University of Texas Press. Ralph W. Yarborough: The People’s Senator, was a finalist in the Western Writers Association and the Robert Kennedy Foundation Book Award for 2002

“Celebrating the life of Carl B. Stokes” a 5 page program

From CSU Special Collections

Metropolis Magazine article about career of Viktor Schreckengost

Viewed from the street, there’s nothing extraordinary or unusual about the house in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, where Viktor Schreckengost has lived since 1952. Big, comfortable-looking, and Tudor-esque in inspiration, it’s typical of the expansive homes built in the Cleveland suburbs in the early twentieth century, when the city was a rising industrial powerhouse.

Inside, however, the house is a veritable museum of Schreckengost’s vast output as one of America’s most important—and under-recognized—industrial designers. It’s also the scene of an unusual family project aimed at perpetuating Schreckengost’s legacy and gaining the national attention that the exceedingly modest designer, now 99, has never sought for himself. The task is daunting: how do you build a reputation for an important creative thinker who largely has been absent from the history books?

Gene Schreckengost, the designer’s second wife, and Chip Nowacek, her son by a previous marriage, have come up with some answers. (Gene and Chip are the aunt and cousin of Metropolis art director Nancy Nowacek.) They’ve incorporated nonprofit and for-profit entities to preserve Schreckengost’s work and intellectual property, and hired a team of researchers to catalog and conserve the contents of his house. Nowacek, who heads the project, has also organized more than 100 small- and large-scale exhibitions across the country this year to celebrate Schreckengost’s 100th birthday, on June 26. He views their work as a way to tell a larger story about his stepfather, whom he sees as a brilliant designer and problem solver who has always been more interested in serving others than in receiving personal attention. “He sort of never got around to taking care of himself,” Nowacek says. “It’s that very attribute that we think is worthy of some notice. Where did all the heroes go? Well, maybe we found one.”

Schreckengost had an immense, if anonymous, impact on American life in his 70-year career. He designed everything: trucks, furniture, industrial equipment, dinnerware, military radar systems, printing presses, stoves, refrigerators, collators, machine tools, lawn mowers, lawn furniture, toys, tractors, streetlights, broadcast equipment, gearshift consoles, flashlights, artificial limbs, typesetting machines, coffins, calendars, chairs, electric fans, lenses, logos, bicycles, ball gowns, and baby walkers. But unlike his better-known peers, including Norman Bel Geddes and Raymond Loewy, Schreckengost never sought fame. Rather than move to New York, where he would have been more visible, he chose to remain in Cleveland and focus on work and teaching at the Cleveland Institute of Art—his real sources of joy. “He never went for self-aggrandizement,” Nowacek says. “I think he viewed it as a distraction.”

In 2000, the year of the first major museum exhibition on Schreckengost’s work, I interviewed him at his home. He showed me a citation he received from the American Institute of Architects when it awarded him a Fine Arts Medal in 1958. Other winners of the award have included Frederick Law Olmsted, Diego Rivera, and John Singer Sargent. “Look at the people on that list,” Schreckengost said modestly. “I just can’t imagine myself being with this group.”

Others, of course, have always seen Schreckengost in such company. Henry Adams, a specialist in twentieth-century American art, stumbled upon the designer in 1994 after moving to Cleveland. Following a hunch, Adams recorded six interviews with the designer, a project that led to a 2000 exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art. This year Adams is writing a 250-page catalog to accompany the centennial shows. “Viktor’s design is modern, but it also has a playful quality to it—almost an anthropomorphic quality,” Adams says. “He’s wildly creative.” The designer’s house, he adds, “is endless. It’s a scholar’s dream.”

After the Cleveland museum show Schreckengost’s loved ones realized they had to start thinking about the future. Gene, a retired pediatrician, attended a local panel discussion on estate planning for artists. She and Nowacek soon realized that they could face heavy taxes after Schreckengost’s death, forcing them or other family members to sell and scatter the contents of the designer’s house, which includes more than 500 artworks worth $3 million to $4 million. “It’s a concern,” Gene says dryly. “If we were hit by a Mack truck, it would be a big problem.”

Confronting the tax questions forced Gene and her son to think more broadly about how to preserve Schreckengost’s work and vision. They created the nonprofit Viktor Schreckengost Foundation to fund projects in education, research, and preservation—plus the for-profit Viktor Schreckengost Intellectual Reserve to earn income for the nonprofit ventures by licensing Schreckengost’s designs. (Not a bad idea: in 2004 Sotheby’s sold an original Jazz Bowl, which Schreckengost designed for Eleanor Roosevelt, for $254,400.) A third organization, soon to be created, will oversee ownership of the house and its contents, and carry out educational projects and exhibitions. The Schreckengosts also hired an eight-person staff—registrars, a photographer, a historian, a merchandising expert, and a graphic designer—to catalog and preserve the contents of the house.

When Nowacek took me on a tour of the house in March, the Schreckengosts were away in Tallahassee, Florida, where they spend the winter. But a painting crew was hard at work getting the house spruced up for the upcoming centennial festivities in June. In the dining room, where Schreckengost usually holds court when visitors come, plastic sheets covered scores of his creations, from mass-produced dinnerware to one-of-a-kind ceramic sculptures and watercolors. (As if he weren’t prolific enough, the designer had a parallel career as an artist.)

On the second floor, the office and library were jammed with personal records, correspondence, and boxes of slides. Other rooms had been given over to the archivists and their computers and files. On the third floor, where Schreckengost did most of his painting and drawing, the archivists had set up a small photo studio to document his paintings, drawings, photographs, ceramics, and sculptures. A skylighted studio at the head of the stairs was still intact—markers, pencils, and brushes lay neatly arrayed on a taboret next to a large drafting table. A 1930s-era Cubist still life of a fish and fruit bowl rested on an easel.

The Schreckengosts have yet to figure out what to do with the house and its contents in the future. Head archivist Craig Bara suggests turning the place into an archive and research center. “My vision is that it becomes Viktor’s legacy,” he says, “the place where his ideas, his techniques, live on, a place where young people would be able to come in and learn.” But the house could also become a public museum, like the Gropius House, in Lincoln, Massachusetts; Russel Wright’s Dragon Rock, in Garrison, New York; and the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, in Oak Park, Illinois. Affiliation with the Cleveland Institute of Art is another possibility. The home could become the setting for residencies or other programs related to Schreckengost’s work at the institute, where he founded the industrial-design department in 1932 and influenced decades of designers.

Of course, establishing a house museum or a research center would mean dealing with visitors, traffic, parking, accessibility for the handicapped, and the potential objections of neighbors—not to mention the City of Cleveland Heights. The Schreckengosts’ approach to such questions has been the opposite of that other famous Cleveland native and designer—Philip Johnson. The man who claimed that immortality is “better than sex” donated his Glass House, in New Canaan, Connecticut, to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1986 while retaining the right to live on the property until he died. Today, a year and a half after Johnson’s death, the National Trust is negotiating with the Town of New Canaan about how to shuttle visitors in and out of the 44-acre estate without disturbing the neighbors. The house and related buildings on the site—including a library, a painting gallery, and a sculpture gallery—could open to visitors as soon as 2007.

The Schreckengosts, true to Viktor’s style, have followed a more modest course. For example, this year’s centennial exhibits will be held not only in predictable venues such as art museums and galleries but also in places that have personal meaning for Schreckengost, including Adam’s Barber Shop, in Cleveland Heights, and a restaurant in Captiva, Florida, called the Bubble Room. The family does have a perfect opportunity to create a public museum similar to the Johnson estate (though certainly on a smaller scale) because they still own Gene’s original home, two doors away, plus a large additional lot that links the two houses. When I telephoned Gene in Florida to ask whether she had considered the idea, she said it hadn’t occurred to her, but she was intrigued and might study its feasibility.

Such discussions raise the delicate question of what Viktor makes of all this. When I asked whether I could speak with him over the phone, Gene said he preferred not to because his hearing aid distorts sound. She also said his poor memory makes it hard for him to carry on a conversation.

But when I asked Nowacek what his stepfather makes of the project to preserve his work and perpetuate his legacy, he said, “He just shakes his head and says, ‘That sounds like a lot of work.’ He’s the same guy he’s always been. He doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about.” Nowacek feels differently: “The amount of work he accomplished—it stuns me. We have to pay attention to the things he churned out.”

Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Meetings. Chicago, Illinois April 12, 2007. William D. Angel, Jr. The Ohio State University at Lima

The link is here

Article by Jeffrey LA Favre

The link is here

News Story from WJW Channel 8 on the 15th Anniversary of Cleveland’s default and the Dennis Kucinich effort to save Muni Light

The link is here

From History.com

The link is here