Curious Cbus:

What’s The History Of Catholics In Columbus?

www.teachingcleveland.org

Editorial: Protect integrity of Ohio’s constitution

Columbus Dispatch 4/2/2017

The link is here

Ohio voters should be given the opportunity to ease the process of initiating state laws.

They also should be given the chance, in a separate ballot issue, to decide if initiating constitutional amendments should be more difficult.

Both would require amending the Ohio Constitution, which only voters can do.

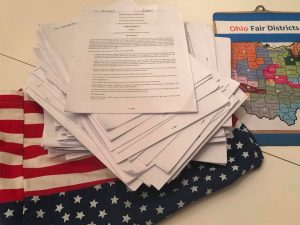

For nearly three years, a committee of the Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission has studied possible changes in initiated statutes and initiated amendments.

Only 15 state constitutions give voters the right to initiate both laws and amendments. The Ohio Constitution has provided those rights since 1912.

Since then, Ohioans using their constitutional rights to engage in direct democracy overwhelmingly have favored the amendment over the statutory route.

Of 80 attempts to initiate policy, petitioners have chosen to try to amend the constitution 68 times (85 percent). Initiated laws have been adopted only three times, most recently in 2006 to restrict smoking in public places.

Statehouse Democrats and Republicans agree that petitioners usually choose the amendment route for two reasons.

First, the requirements for getting on the ballot are nearly as difficult, and therefore nearly as costly, for a proposed law as for a proposed amendment.

Qualifying a proposed law for the ballot requires petitioners, as a first step, to collect signatures equal to 3 percent of the electorate. The proposal then goes to the General Assembly, which has four months to adopt, reject or modify it.

If the legislature rejects or modifies the proposal in a way unacceptable to petitioners, they must restart the petition drive and collect an additional 3 percent, totaling 6 percent of the electorate.

Second, even if Ohioans proposing an initiated law are successful in the election, nothing prevents the legislature from later repealing or amending the voter-approved statute.

Given these disincentives, petitioners rationally choose the amendment route. Voter-approved amendments, like the rest of the constitution, can only be changed by a public vote.

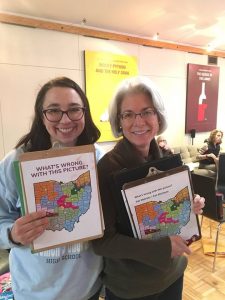

As a result, over time the Ohio Constitution becomes weighted with ornaments more suited to the Ohio Revised Code, such as livestock-care standards and casinos.

That’s why the modernization commission is considering how to ease the process of initiating state laws, and how to make the amendment process more difficult.

An idea gaining momentum is to create a 5 percent signature requirement for initiated laws, eliminate the supplementary petition requirement, and prohibit the General Assembly from changing any voter-enacted law for five years, except by a two-thirds vote.

Such a proposal has merit standing alone. However, majority Republicans appear intent on marrying it to a proposal requiring proposed amendments to receive 55 percent approval to win passage. Republicans also want to restrict initiated amendments to general elections in even-numbered years.

Some states have supermajority requirements for voter-initiated constitutional amendments. Florida, for example, requires 60 percent approval. Nevada requires a majority vote in two consecutive elections.

There is much to commend efforts to make initiated laws easier and initiated amendments harder.

However, the cleanest way to present these alternatives to voters is in two separate issues, not a combined one. When dealing with proposed changes to fundamental constitutional rights, voters should have an opportunity to judge each on its own merits.

Originally appeared in Columbus Dispatch. Reprinted with permission

Reprinted by permission

Original link is here

Editorial: Ohio Constitution deserves bipartisan review

Columbus Dispatch 3/23/2107

Thursday

State lawmakers should grant a reprieve to the Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission. The 32-member body, diligent but underappreciated, is set to expire prematurely at the end of this year.

The unapologetic executioner is state Rep. Keith Faber, R-Celina, who — as Senate president last session — slipped a poison pill into the state budget to kill the commission.

Now that Faber again is a House freshman, House Speaker Cliff Rosenberger and Senate President Larry Obhof have an opportunity to redress Faber’s petulance, show prudence, and allow the commission to fulfill its original promise.

Under the leadership of former Speaker William G. Batchelder, the commission began in October 2011. It was given a decade to work, to expire July 1, 2021.

The Ohio Constitution deserves a periodic, methodical and bipartisan review, which is what has been occurring since the commission got rolling in 2014.

The late start was largely attributable to Faber’s reluctance to help get commissioners appointed and staff hired.

The constitution, 166 years old, is the nation’s sixth oldest. At nearly 57,000 words, it’s the 10th longest. With such age and length comes obsolete provisions and archaic constructions.

Because the state is not likely to hold another state constitutional convention in the foreseeable future (the last was in 1912), a bipartisan commission of respected individuals should be impaneled once every two decades to examine potential amendments for a public vote.

Since 2014, the commission has performed valuable service. It paved the way for two amendments approved by Ohio voters in November 2015, providing for apportionment reform and anti-monopoly safeguards.

Near the end of last year, the commission sent to the General Assembly proposals to eliminate several obsolete sections of the constitution. If sent to the ballot and approved by voters, they would eliminate:

‒ Courts of conciliation, created in 1851 to allow resolution of disputes outside the traditional legal process. They’ve never been used, and long ago were replaced by modern arbitration proceedings.

‒ The Supreme Court Commission, created in 1875 to relieve backlogs of cases. It has not been used since 1885.

‒ Sections authorizing specific debt and bonding authority for projects long ago accomplished with debts long ago paid off.

‒ Provisions on the Sinking Fund Commission, whose responsibilities long ago were taken over by the state treasurer.

Like the legislature itself, the commission works through standing committees, which hear testimony and compile research. The commission’s body of research, available on its website, is a model of objective, detailed analysis — a treasure for researchers and policymakers.

The commission has not yet dived into the constitution’s sections on the executive branch, the elective franchise, the militia, and a few other areas.

One of its committees is attempting to find compromise on an amendment that would make it easier for voters to enact initiated laws, but more difficult to enact initiated amendments.

This is highly sensitive territory, requiring bipartisan diplomacy and outreach to a broad spectrum of interest groups.

Since 1912, the Ohio Constitution has given voters the power to directly initiate constitutional amendments, bypassing the General Assembly. Ohio is one of only 16 states with that provision, and one of only 11 where enactment requires only a simple majority vote.

The committee has discussed requiring a 55 percent vote to amend the constitution. This deserves patient, extensive review. Pulling the plug on the commission sends the opposite message — one of callous indifference.

Trump to save coal, nuclear plants that are unable to compete (6/1/2018) Plain Dealer

Developers update Cleveland City Council on lakefront plans (5/30/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

K&D strikes deal to buy 55 Public Square office tower, with mixed-use renovation plans (5/30/2018) Plain Dealer

Cleveland police recruitment plan says more women, minority officers needed to reflect city’s diversity (5/29/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga Community College trustees approved a nearly 10 percent tuition increase Thursday (5/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Bedrock’s May Co. building redo getting ready to roll (5/23/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Younger Ohioans Urged To Register And Vote, But Stats Show Historically, They Don’t (5/22/2018) Ideastream

FirstEnergy must guarantee nuclear clean up, environmental groups tell feds (5/22/2018) Plain Dealer

Have opioid deaths in Northeast Ohio finally crested? Evidence suggests yes (5/21/2018) Cleveland.com

Shoreline Erosion: Changes threaten Lake Erie coast (5/19/2018) Sandusky Register

Lake Erie rescue project is boosted by construction of West Side tunnel (5/18/2018) Plain Dealer

Teacher pay varies widely across region (5/17/2018) Dayton Daily News

Scientists Say Lake Erie Toxic Algae Blooms Could Be Part of Climate Change Loop (5/16/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio Board of Education to Consider Delaying Overall Grades for School Districts (5/13/2108)

New plan shows how CWRU can grow within boundaries and be greener, more welcoming (5/13/2018) Plain Dealer

Here are the 9 most interesting storylines from this week’s Ohio primary election (5/11/2018) Cleveland.com

Mike DeWine wins Republican primary in Ohio governor’s race (5/9/2018) Clefveland.com

Cordray wins the Ohio Democratic governor’s primary (5/9/2018) Cleveland.com

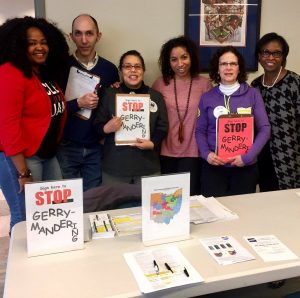

Ohio votes to reform congressional redistricting; Issue 1 could end gerrymandering (5/9/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio primary: Voters pick candidates for one of the year’s biggest governor races (5/8/2018) Washington Post

Report Finds Big Gaps in Regional Employer Needs, Employee Skills (5/8/2018) Cleveland Scene

Federal forecasters said Monday that this summer’s Lake Erie algal bloom could reach the size of last summer’s bloom–the 3rd-largest on record (5/7/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio’s School Districts Struggle to Cover Lost Transportation Funding (5/7/2018) Cleveland Scene

The Browns Are Already Talking About a New Stadium or Major Renovations (5/3/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio Issue 1 Q&A: congressional redistricting and the ills of gerrymandering – Election preview (5/3/2018) Cleveland.com

Algal blooms harder to control because of climate change, other factors, data shows (5/1/2018) Toledo Blade

Closing FirstEnergy’s reactors will not destabilize grid, says PJM, but launches probe into future fuel security (4/30/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio has ‘long way to go’ to solve Lake Erie’s algae problem, state officials say (4/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Ford’s Move to End Most U.S. Car Production Will Force Ohio Parts-Makers to Adjust (4/28/2017) WOSU

Communities across the state need to take more action to keep Lake Erie clean, Ohio EPA says (4/27/2018) News5

FirstEnergy Solutions definitely to close its nuclear power plants (4/25/2018) Plain Dealer

Issue 1 Could Remake How Ohio Draws Congressional Districts (4/23/2018) Ideastream)

Cleveland, Akron media shakeups bring job cuts (4/22/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Why Cleveland Hopkins airport has more passengers, lower fares despite fewer destinations (4/22/2018) Cleveland.com

Worried, sick and weary, Puerto Rican families settle in Cleveland (4/20/2018) Cleveland.com

Greater Cleveland RTA ridership drops 9.5 percent to record low in 2017 (4/19/2018) Cleveland.com

Campaign for Ohio congressional redistricting reform is low-profile and low-budget (4/18/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio legislators look to clamp down harder on communities that try to pass local gun restrictions (4/17/2019) Cleveland.com

Should school districts get an A-F grade? State report card overhaul debated (4/17/2018) Plain Dealer

Has the Cleveland Plan for school improvement stalled? Maybe not, but test scores have (4/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Medicaid expansion has helped, but poverty persists in Ohio (4/13/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Ohio and Cleveland gain little on “Nation’s Report Card,” as national scores stay flat (4/10/2018) Plain Dealer

As the opioid epidemic rages, the fight against addiction moves to an Ohio courtroom (4/8/2018) Washington Post

FirstEnergy’s efforts to re-make itself into a delivery-only electric utility — has many people worried that power plants will shut down and Ohio will run short of electricity (4/8/2018) Plain Dealer

Ground broken for The Lumen at Playhouse Square, billed as largest downtown residential project in 40 years (4/5/2018) Plain Dealer

A Cleveland Landfill Will Host Ohio’s Largest Solar Farm (4/5/2018) WOSU

Ohio exports to China in crosshairs of looming trade war (4/4/2018) Columbus Dipatch

Ohio State’s shrinking share of low-income students (4/3/2018) The Lantern

Students in gun-control movement turn from marches to elections (4/2/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Among counties, Cuyahoga near top in Midwest for attracting immigrants (4/2/2018) Cleveland.com

Congolese part of new tapestry of immigration to Cleveland (4/1/2018) Plain Dealer

In Cleveland’s Superior Arts District, development activity stokes optimism – and some fears (4/1/2018) Plain Dealer

Report documents Ohio’s job slide, presses candidates for solutions (3/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Cleveland’s 2018 budget includes millions of dollars dedicated to police reform (3/29/2018) Cleveland.com

FirstEnergy Solutions asks DOE to help save its old power plants (3/29/2018) Plain Dealer

FirstEnergy Solutions will close its nuclear power plants (3/28/2018) Plain Dealer

State’s new education plan gets warm reception from Cuyahogs County residents (3/28/2018) Plain Dealer

Stuck in dial-up age, rural Ohio still pushing for high-speed internet (3/25/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Students lead thousands in March for Our Lives rally on Public Square (3/24/2018) Cleveland.com

FirstEnergy Solutions bankruptcy restructuring likely, power plants would be closed or sold (3/23/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio says for the first time it’s declaring western Lake Erie impaired by the toxic algae that has fouled drinking water in recent years (3/22/2018) Associated Press

Ohio Senate backs change in teacher evaluations over Cleveland objections (3/22/2018) Plain Dealer

Spending bill before Congress would keep $300 million for Great Lakes programs (3/22/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga County Council lacks confidence in administrators, council president says (3/20/2018) Cleveland.com

Playhouse Square to lift curtain on 34-story apartment tower (3/19/2018) Plain Dealer

Cleveland schools’ plan shifts focus to K-8 (3/18/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Ohioans Divided Over Education Consolidation Bill (3/15/2018) Cleveland Scene

Cuyahoga County Ranks Worst In Ohio For Low Birthweights (3/14/2018) Ideastream

Ohio farmers fear retaliation from tariffs (3/14/2018) Dayton Daly News

What you should know: Ohio’s proposed merger of education, training agencies moving quickly (3/13/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Is 16 years old too young to drive? Ohio lawmakers consider upping age for a license (3/13/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Transparency, voter voice concerns spark opposition to state education merger, limits to board (3/12/2018) Plain Dealer

New Ohio education goals put emotional health, critical reasoning and job skills on par with English and math (3/12/2018) Plain Dealer

Political barriers still daunting for Ohio women (3/10/2018) Dayton Daily News

Ohio’s natural-gas production rose in 2017, but ample supply meant low profits (3/9/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Education merger bill attracts overflow crowd of opponents (3/8/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Federal plan calls for phosphorus reductions to improve Lake Erie water (3/8/2018) Toledo Blade

One University Circle prepares to open its doors in April (3/8/2018) Fresh Water

MetroHealth transformation project set to bring major changes to surrounding neighborhood (3/6/2018) News5

Can This Judge Solve the Opioid Crisis? (3/5/2018) New York Times

Ohio wants to improve school security after Florida shootings, but officials have no plan yet (3/4/2018) Plain Dealer

State of the State: Job prospects and quality of life improve, economy slow to recover (3/4/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Cleveland Wants to Connect the Dots with Hundreds of Miles of Greenways (3/2/2018) Next City

The middle class is getting left behind. And it’s happening in Ohio at a higher rate than other states (3/1/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Ohio casinos: They’ve fallen short of projections, and here’s why (3/1/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Cleveland-area house prices ended 2017 up 3.5 percent, Case-Shiller finds (2/27/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio Joins Cities, Counties, Other States In Filing Lawsuit Against Prescription Pill Distributors (2/26/2018) Ideastream

Rowing center, RTA’s Brookpark Station on Greater Cleveland Partnership’s wish list for capital budget (2/26/2018) Cleveland.com

Will Euclid’s new master plan reboot an aging, inner-ring suburb? (2/25/2018) Plain Dealer

Republican Ohio governor candidates support arming teachers to help prevent school shootings (2/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Planned Landfill Solar Farm is Expected to Save Money for Cuyahoga County (2/21/2018) WKSU

Some Ohio Community Colleges Could Soon Offer Bachelor’s Degrees (2/20/2018) WOSU

MAY 8, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTION Issues List from the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections (2/19/2018)

MAY 8, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTION Candidate List from the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections (2/19/2018)

Northeast Ohio Angling For Piece Of Multibillion-Dollar Film Industry (2/19/2018) WOSU

Ohio will try to exempt residents from Obamacare mandate to get insurance, and add work requirement for some on Medicaid (2/16/2018) Cleveland.com

MetroHealth’s finances are looking good (2/16/2018) Modern Healthcare

NOACA signs agreement with Hyperloop Transportation Technologies to explore Cleveland-Chicago routes (2/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Helping students? Or power grab? Governor would take power from elected state school board members in merger (2/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Opportunity Corridor is back on track for 2021 completion after delay caused by taxpayer lawsuit (2/14/2018) Plain Dealer

Half of Ohio is an ICE ‘Border Zone’ — Here Are the Rights Immigrants Should Know (2/9/2018) Cleveland Scene

Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish is unopposed for re-election (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Four judges file for two Ohio Supreme Court seats (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Down ticket Ohio races feature a few May primaries (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio Senate passes bipartisan congressional redistricting plan (2/5/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland Hopkins to update master plan in wake of dramatic changes at airport (2/4/2018) Plain Dealer

Will lack of LGBT protections cost Ohio Amazon HQ2, other business? (2/3/2018) Columbus Dispatch

State Auditor To Push For One-Time Audit Of JobsOhio (2/1/2018) WOSU

Ohio Supreme Court rules against Cleveland’s efforts at local gun control (1/31/2018) Cleveland.com

Despite state, local efforts, human trafficking jumps by 38% in Ohio (1/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Chief Wahoo, the longtime logo of the Indians, will be gone after the 2018 season (1/29/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s inner-ring suburbs still hurting from the housing bust, despite addressing blight (1/28/2018) Plain Dealer

After robust 2017, Port Authority anxiously awaits U.S. decision on tariffs (1/28/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

More Lake Erie walleye caught in 2017 than in 30 prior years (1/26/2018) Buffalo News

FirstEnergy executive: Davis-Besse plant headed for premature closure (1/25/18) Toledo Blade

‘Right to work’ could be on the ballot in Ohio with support from lawmakers (1/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Court-enforced Cleveland police reforms continue to be a mixed bag, monitor says (1/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio among northern states to lose another U.S. House seat after next census (1/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga County seeks two-year renewal of health and human services tax (1/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Davis-Besse, Perry nuclear plants could close as FirstEnergy inks deal with hedge funds (1/23/2018) Plain Dealer

At 100, the Cleveland Orchestra May (Quietly) Be America’s Best (1/22/2018) New York Times

The Secret Amazon Bid Dramatizes a Huge Cultural Problem in Cleveland. The Media Can Do Something About It (1/22/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio cities take tax fight with state to court (1/21/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Cleveland Hopkins passenger volume tops 9 million for the first time since 2013 (1/19/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Columbus makes Amazon first cut for second HQ (1/18/2018) Columbus Dispatch

US Supreme Court takes on internet sales tax case with implications for Ohio (1/18/2017) Columbus Dispatch

Controversial mayor’s courts abound in Cuyahoga County (1/17/2018) Cleveland.com

Justice Center to be Cuyahoga County’s most expensive endeavor (1/16/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s settlement houses persevere, even as they struggle with funding and obscurity (1/16/2018) Cleveland.com

RTA’s Long History Of Reliance On Sales Tax May Be Reaching Breaking Point (1/15/2018) Ideastream

The ‘build it and they will come period is over’ for downtown Cleveland apartment market (1/14/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Charter school failure could be largest in Ohio history (1/12/2017) Dayton Daily News

Why GOP redistricting plan flunks test to rid Ohio of gerrymandering (1/11/2018) Cleveland.com

MetroHealth unveils plan to turn main campus into ‘hospital in a park’ (1/10/2018) Plain Dealer

RTA will make cuts because of lost taxes, counties struggle as well (1/9/2018) Plain Dealer

What attributes should a high school graduate have? It’s not just the “three R’s” anymore (1/7/2017) Plain Dealer

Ohio voter challenges election roll purge in U.S. Supreme Court clash (1/4/2017) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Extended cold snap has water mains bursting around Greater Cleveland (1/4/2017) Cleveland.com

Transportation Official Worries About Funding For Ohio’s Roads (1/3/2017) WOSU

Test scores need to stay in teacher ratings, says Cleveland schools CEO (1/3/2017) Plain Dealer

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson sworn in for record fourth 4-year term in office (1/2/2017) Cleveland.com

Less than one in a million.

Those are the chances a noncitizen will be found guilty of illegally voting in a statewide election in Ohio. It’s not because authorities aren’t doing all they can to detect and prosecute voter fraud. It’s because votes cast by noncitizens are extremely rare. And, nearly all result from honest mistakes, not fraud.

Once again, Secretary of State Jon Husted has performed a valuable public service by reporting on efforts to identify cases of potential voter fraud and referring them for possible prosecution.

Husted reported that 82 noncitizens voted in 2016. They were among 385 noncitizens improperly registered to vote. Combined with the numbers from the 2012 and 2014 elections, there have been 821 improper registrations and 126 improperly cast ballots. In those three elections, nearly 14.4 million Ohioans went to the polls.

So, for starters, over three statewide elections, a noncitizen cast an improper ballot for every 114,285 voters going to the polls. And, if Husted’s 2016 referrals follow the same pattern as those for 2012 and 2014, prosecutors will find that fewer than 1 in 5 deserve to be charged, and fewer still will be found guilty.

Following the 2012 and 2014 elections, Husted’s efforts resulted in a total of 44 cases of potential fraud being referred. After prosecutors examined the evidence, eight people were charged. Five were convicted. One went to a diversion program. The other two cases were sealed.

Bottom line: Even if all eight of those prosecuted had been convicted, they represent less than one voter in a million. In the 2012 and 2014 elections, nearly 8.8 million Ohioans went to the polls.

Why are noncitizens referred for investigation and possible prosecution so rarely charged? And so rarely found guilty? According to spokesmen for Husted and Attorney General Mike DeWine, prosecutors are much more likely to find honest mistakes than criminal intent. And those honest mistakes are not always the fault of the noncitizen voter; they sometimes are the mistakes of those who register voters and process voting rolls.

Since 1995, federal law — the so-called Motor Voter Law — has required motor vehicle registrars to offer customers the opportunity to register or re-register to vote.

From 2012 through 2016, Ohio’s deputy registrars have registered 896,601 new voters. Given such volume, it’s not rare for a noncitizen — oftentimes with limited English proficiency — to have a voter registration form placed in front of him. And for a mistake to happen.

Prosecutors frequently determine that a noncitizen who registered to vote never intended to register, said DeWine spokesman Dan Tierney. “Sometimes they fill it out truthfully and it still gets through the system,” he said.

Given the rarity of voter fraud in Ohio, some have criticized Husted for devoting so much time and effort to track and report on it.

The Dispatch believes otherwise. The secretary of state is morally and legally obligated to protect the sanctity of the vote. A periodic examination educates the public, puts citizens and noncitizens on notice, and serves as a deterrent.

Voting rights advocates should welcome the vivid illustration of the rarity of voter fraud in Ohio. The plain facts disprove the wearisome claims about rampant voter fraud, made to justify efforts to enact tougher voter ID laws and other restrictions.

Voter fraud is likely at an all-time low in Ohio. That’s something to cheer.

News Aggregator Archives: FEATURE area 2017

Untouchables: The Making of the Memoir That Reclaimed a Prohibition-Era Legend (12/27/2017) Vanity Fair

In the sales pitch to Amazon, a reimagined downtown Detroit (12/20/2017) Crain’s Detroit Business

What’s really behind GCRTA’s falling ridership levels (12/17/2017) Tim Kovach

The Cosgrove era comes to a close (12/11/2017) Crain’s Cleveland Business

How a Cleveland City Council Campaign Fund Rewards Allies and Stifles Dissent (12/6/2017) Cleveland Scene

In Today’s Ohio, ‘Home Rule’ Is Not About Cities Being Self-Governed; It’s Cover For State Officials Moving Economic Growth To The Exurbs by Tom Bier (12/5/2017) Belt

Ohio is watching a “transit death spiral” unfold (12/4/2017) Mark Lefkowitz Green City Blue Lake

Cleveland’s Outer Neighborhoods Could Be The Key To The Future (12/4/2017) Cleveland Magazine

Leonor’s Choice (11/20/2017) Cleveland Magazine

Video from the “2018 Ohio Political Crystal Ball” forum (11/17/2017)

The Man Dead Set On Building an Offshore Wind Farm on Lake Erie (11/17/2017) Smithsonian

A historic look at Cleveland’s settlement houses (11/16/2017) Cleveland.com

From Desegregation to School Choice: How the Civil Rights Era Influenced the Cleveland Schools of Today (11/15/2017) Ideastream

Innovations from Cleveland’s urban farms are taking root around the world (11/9/2017) FreshWater

43 photos honoring the 50th anniversary of Carl Stokes election as Mayor of Cleveland (11/9/2017) Cleveland.com

The 50 Year Policy Legacy of Mayor Carl B. Stokes-video (11/3/2017) City Club of Cleveland

Video from “Nuts and Bolts of Ohio Campaign Finance” forum 10/26/2017

Taking On the Man Four Women Vying for Seats on a Male-Dominated Cleveland City Council (10/25/2017) Cleveland Scene

Doing urban history in Cleveland-a personal reflection: Todd Michney (10/19/2017) The Metropole

Video from “Home Rule” forum at Lakewood Library (10/17/2017)

Redistricting ‘reform’ brought to you by Ohio GOP leaders scared of a ballot issue: editorial (10/11/2017) Cleveland.com

Why Ohio’s recent effort to update its constitution fell short: Steven H. Steinglass (10/8/2017) Cleveland.com

“People were saying nice things about Cleveland again”: reflecting on Carl Stokes and city image by J. Mark Souther (10/5/2017) Metropole

Housing Dynamics in Northeast Ohio: Setting the Stage for Resurgence by Thomas Bier (September 2017) Cleveland State

Why a Cleveland Church Group Challenged Big Stadium Money by Daniel J. McGraw (9/26/2017) Next City

Why the Midwest can’t afford new cuts to immigration (9/26/2017) Chicago Business

Video from “Ohio Board of Education” forum (9/25/2017)

Shock swept nation when My Lai massacre photos first published by The Plain Dealer (9/24/207) Plain Dealer

Video from “Ohio Drug Price Act-Issue 2” forum (9/19/2017)

How to Save a Dying Suburb (9/19/2017) CityLab

On the 40th anniversary of “Black Monday 9/19/1977-an oral history by Vince Guerrieri (9/19/2017) Belt

Community Discussion – Politics, Facts and Compromise: Will It Happen? (9/17/2017) Video from 1st Unitarian Church

Reconsidering Dennis Kucinich 40 years after his Cleveland mayoral run: Richard M. Perloff (9/17/2017) Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s rich industrial past inspired the arts: PD 175 (9/17/2017) Plain Dealer

Capturing the next economy: Pittsburgh’s rise as a global innovation city (9/13/2017) Brookings

Nonprofits dominate Pittsburgh’s economy, development and government (9/11/17) Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

How the Group Plan of 1903 molded Cleveland (9/7/2017) Plain Dealer

Cleveland’s obsession with gentrification is worryingly premature by Alex Baca (9/5/2017) Cleveland Magazine

National City Bank to Marble Room: A visual history of Cleveland’s storied bank building (9/5/2017) Cleveland.com

Video from the Cleveland Mayoral Candidate Forum (8/30/2017) Cleveland Public Library

Video from “The Election for Mayor: A discussion about the future of Cleveland” forum (8/29/2017)

There’s Something the Matter With Ohio Too (8/29/2017) Bloomberg

The case for raising the minimum wage in Ohio by Michael Curtin (8/26/2017) Columbus Alive

Tape from Cleveland Mayoral forum (8/25/2017) City Club of Cleveland and others

West Shoreway $100M re-do brings benefits, but falls short of original vision: Steven Litt (8/23/2017) Plain Dealer

How Redlining Segregated Chicago, and America (8/22/2017) Chicago Magazine

Harnessing the wind: Ohio ranks among top 10 for distributed wind energy (8/19/17) Lima.com

Eight is enough. The 2018 Ohio governor’s race (8/15/2017) Columbus Monthly

Kids of King Kennedy are trapped by a brick ceiling: Mark Naymik (8/13/2017) Cleveland.com

Burning river reborn: How Cleveland saved the Cuyahoga – and itself (8/8/2017) Christian Science Monitor

105th and Euclid: The Winston Willis Story (8/3/2017) Medium

What the History of One Cleveland Neighborhood Can Teach Us About Race and Housing Inequality (8/2/2017) Cleveland Scene

What the Cuyahoga River means to Cleveland (8/1/2017) Cleveland Magazine

Kyle Dreyfuss-Wells is Reining in the Rain (8/1/2017) Cleveland Magazine

Moses Cleaveland trees: How many centuries-old trees are left today? (7/26/2017) Cleveland.com

Meet William Stinchcomb, the visionary behind creating the Cleveland Metroparks-Video (7/20/2017) Cleveland.com

The unforgettable Judge Jean Murrell Capers: editorial (7/20/2017) Cleveland.com

How the Cleveland Clinic grows healthier while its neighbors stay sick (7/17/2017) Politico

Report urges overhaul of troubled (PA) State System universities (7/13/2017) Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Carl Stokes-Promises Now Sadly Faded (July 10, 2017) Roldo Bartimole

Pittsburgh’s Latino community is small, diverse, growing — and anxious. (7/10/2017) Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Record Rendezvous: Cleveland cradle of rock ‘n’ roll sits empty, awaits new life (7/9/2017) Cleveland.com

John Spenzer, Cleveland’s first forensic scientist, loomed large 100 years ago (7/9/2017) Cleveland.com

There’s work to do to streamline Ohio Constitution (7/9/2017) Columbus Dispatch

How these wealthy Cleveland-area families acquired their fortunes (7/6/2017) Cleveland.com

The Time Cleveland Released 1.5 Million Balloons to Disastrous Effects (7/3/2017) Cleveland Scene

In Cleveland, climate change isn’t about rising seas. It’s about jobs and health (6/29/2017) PRI

Many small colleges face big enrollment drops. Here’s one survival strategy in Ohio (6/29/2017) Washington Post

2018 Ohio gubernatorial scramble revs up after next week’s budget signing: Thomas Suddes (6/24/2017) Cleveland.com

How to Combat Food Insecurity in Ohio-Video (6/23/2107) City Club

Results from Irish Town Bend forum and link to proposal (6/22/2017) Plain Dealer

One Ohio Town’s Immigration Clash, Down in the Actual Muck (6/18/2017) New York Times

Dan Egan, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter and author of The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, delivers the annual State of the Great Lakes address. (6/9/2017) City Club of Cleveland

Cleveland’s maritime muscle: Vintage photos of the city’s docks and port (6/6/2017) Cleveland.com

Beyond “white flight”: what the history of one Cleveland neighborhood can teach us about race and housing inequality By Todd M. Michney (5/31/2017) Belt Magazine

Cleveland girl’s spelling victory created racial controversy, national headlines in 1908 (5/30/2017) Cleveland.com

Nor Any Drop to Drink?: Why the Great Lakes Face a Murky Future (5/23/2017) New York Times

How food is bringing the rust belt out of its decades-long recession (5/17/2017) Thrillist

Why is Cleveland different than Cincinnati? It all comes down to history (5/17/2017) Cleveland.com

Fracking and the Impact of the Utica Shale on Ohio (5/16/2107) video

Dreaming up Western Reserve — the 51st state? (5/15/2017) a series from Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s legendary Leo’s Casino made music history, transcended race (5/14/2017) Cleveland.com

From Outhwaite to Advocate – Public Housing & the Stokes Legacy (video) May 2017 Ideastream

Historical chat w/Fred Samsel on his early #CuyahogaRiver clean-up efforts (5/11/2017) FreshWater

Video from East Side Development forum May 9, 2017 moderated by Terry Schwarz

From a Maine tribe, a message for the Cleveland Indians: Enough is enough (5/9/2017) Boston Globe

From 1930s redlining to now: Terry Schwarz panel to discuss why East Side development lags (5/6/2017) Cleveland.com

One City in Pennsylvania is Poised to Crush the 21st Century (4/29/2017) BizPhilly

Cleveland’s sports history filled with highs, lows, villains and heroes: PD 175th (vintage photos) (4/29/2017) Plain Dealer

The Future of Offshore Wind in Northeast Ohio Panel-Video 4.28.2017 (City Club of Cleveland)

The Battle for the Right to Vote in Ohio-Video (April 2017) Western Reserve PBS

In Cleveland, co-op model finds hope in employers rooted in the city (4/27/2017) Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Our costly addiction to healthcare jobs (4/22/2017) New York Times

Video from “Foster Care in Northeast Ohio forum (April 18, 2017)

NFL revenue gap could drive more relocation (April 18, 2017) USA Today

CLE classic: Viktor Schreckengost combined form, function and beauty (April 2017) Freshwater

When Larry Doby broke the American League color barrier in Cleveland: Nicolaus Mills (4/12/2017) Cleveland.com

Built on Steel, Pittsburgh Now Thrives on Culture (4/12/2017) New York Times

The Preston model: UK takes lessons in recovery from rust-belt Cleveland (4/11/2017) The Guardian

Cleveland Clinic co-founder George Crile helped meet medical challenge of World War I – part three of series (4/4/2017) Plain Dealer

Thousands of Ohio soldiers fought and died ‘over there’ in World War I -part two of series (4/3/2017) Plain Dealer

100 years ago, U.S. entry into bloody World War I changed everything (4/2/2017) Plain Dealer

Building the bridges of Cuyahoga County (vintage photos) (3/30/2017)

Take a tour of Cuyahoga County’s 109 historical markers (3/24/2017) Cleveland.com

The Impact of Ohio Budget Cuts on NE Ohio Communities, including Preview, Summary and Video 3/21/2017

A brief history of fights, feuds and a coup at Cleveland City Hall (3/16/2017) Cleveland.com

The History of Irish Town Bend-Video (3/15/2017) Cleveland.com

Cleveland was the First City of Light. A call for a “Festival of Lights” in Cleveland by Chris Ronayne (3/15/2017) Cleveland Magazine

The Great Lakes are sicker than we think (3/9/2017) Belt

Reissuing a special 1961 magazine celebrating Cleveland’s first 165 years (3/7/2017) Cleveland.com

Transit alone cannot solve the systemic problems behind job inaccessibility (3/7/2017) a two part essay by Tim Kovach Part 2 is here

Report Shows Voter Fraud is Rare in Ohio: editorial (3/5/2017) Columbus Dispatch

Cleveland’s dividing lines over race issues come to light under Trump (3/3/2017) The Guardian

Women’s History Month: Cleveland suffragettes, protests and parades since 1869 (3/2/2017) Cleveland.com

Today, March 1, is the anniversary of Ohio Statehood (Video) History.com

Catching up with Jane Campbell (2/10/2017) Cleveland Magazine

WATCH: Lake Shore Power Plant smoke stack comes crashing down (2/24/2017) Fox8

Edwins Restaurant in Cleveland Offers Ex-Offenders a New Start (2/22/2017) Paste

Why Ohio Is The Best State In America To Launch A Start-Up (2/20.2017) Forbes

The most historic place in each of Ohio’s 88 counties (2/17/2017) Cleveland.com

John D. Rockefeller Was the Richest Person To Ever Live. Period (January 2017) Smithsonian

Opioid overdose crisis plagues Cleveland (2/9/2017) CBS

Northeast Ohio agencies prepare for booming ‘silver tsunami’ (2/9/17) Freshwater

The legend of Moore (2/7/2017) St. Ignatius Enews

Akron Has a New Plan to Boost Its Shrinking Population (2/7/2017) NextCity

Ohio energy sources 1) Coal Mining 2) Natural Gas (February 2017) Westlake/Bay Village Observer

Ohio County was a poster child of voter fraud (2/3/2017) by Michael F. Curtin

“Proposed Merger of Cleveland and East Cleveland” forum video (1/31/17)

Ohio Was A Bellwether After All (1/25/2017) FiveThirtyEight

Transportation’s Role in the Economic Restructuring of Cleveland (1/2017) Cleveland State University

What should be done about East Cleveland? (1/19/17) Cleveland.com

When Martin Luther King Jr. Brought His Fight to Cleveland (1/16/2017) Ideastream

Where Educated Millennials Are Moving (1/13/17) Forbes

The Symbol of the City – The Cleveland Flag (1/9/17) Tom Horsman

175 years of telling Cleveland’s story-special anniversary issue (1/8/17) Plain Dealer

Decision on fate of pedestrian bridge needs grounding in stronger lakefront vision (1/5/2017) Cleveland.com

Lead in Cleveland: Confronting a Silent Killer (1/5/2017) Freshwater

A Year That Can Never Be Taken From Cleveland (1/1/2017) New York Times

Meet William Stinchcomb, visionary behind creating the Cleveland Metroparks, video from Cleveland.com 7.20.2017

The Cleveland Metroparks will be celebrating its 100-year anniversary this weekend, so we thought it appropriate to share the history of one of the parks driving forces — William Stinchcomb.

Gov. John Kasich keeps swinging his ax at Ohio’s state income tax.

When he launched his 2010 campaign, Kasich revealed a dream of abolishing the tax. He won’t accomplish that, but his fourth and final budget proposal represents his fourth consecutive whack at it.

“We’ll march over time to destroy that income tax that has sucked vitality out of this state,” Kasich declared at his 2010 campaign kickoff.

The nexus between Ohio’s income tax and its economic fortunes is questionable. Forty-three states have income taxes. As of 2014, Ohio’s per-capita income-tax burden ranked 34th, says the conservative Tax Foundation.

In the modern era, conservatives argue the tax punishes initiative and slows economic growth. Progressives defend graduated income taxes as essential for reducing the average Joe’s overall tax burden.

This ideological fault line didn’t always exist. In the early 1900s, as the Progressive Era gained steam, federal and state leaders — Democrats and Republicans — simultaneously took interest in the idea of taxing incomes.

In September 1906, Republican Gov. Andrew L. Harris appointed a five-man tax commission “to investigate the tax laws of this state and to make recommendations for their improvement.”

In June 1909, President William Howard Taft, a Republican, proposed a constitutional amendment giving Congress the power to levy income taxes; the amendment was ratified in 1913.

The work of Ohio’s tax commission prompted delegates to the state’s 1912 constitutional convention to consider a state income tax. The question was put to Ohio voters that September. By a 52-48 vote, Ohioans authorized the General Assembly to consider income taxes, with uniform or graduated rates.

The General Assembly was not quick to use this authority. As the 20th century unfolded, the state looked elsewhere for revenues. In response to needs created by the Great Depression, in 1934 Ohio enacted a statewide sales tax of 3 percent. In 1967, it was raised to 4 percent.

However, pressures for an income-tax increased throughout the 1960s. In 1962, Tax Commissioner Stanley J. Bowers predicted Ohio would need an income tax within five years, primarily to relieve excessive burdens placed on real estate and personal property.

In 1968, a tax-study committee led by state Rep. Albert H. Sealy, R-Dayton, held 24 hearings across the state. Business interests, led by the Ohio Farm Bureau, the Ohio Contractors Association and the Ohio Hardware Association, voiced support for an income tax to offset the hated personal-property tax, which bore no relation to profitability.

In December 1971, after a half-century of buildup, Democratic Gov. John J. Gilligan and a Republican legislature adopted a state income tax, with rates ranging from 0.5 to 3.5 percent. The Republican game plan was to give Gilligan just enough votes to pass the tax, then clobber him with it in 1974.

When conservatives led by state Rep. Robert Netzley qualified a repeal for the November 1972 ballot, Ohio Republican Chairman John Andrews worked behind the scenes in opposition. The Ohio GOP platform that year remained silent on the issue. The repeal failed by more than 2 to 1. There were many reasons for Gilligan’s subsequent defeat, but the GOP tax strategy was pivotal.

The 1981-82 recession prompted Republican Gov. James Rhodes — a master of the “temporary tax” — to win approval of a 50 percent increase in the income tax. His successor, Democrat Richard Celeste, solidified it, adding another 40 percent over pre-1982 levels.

Those increases prompted another repeal effort, this time led by conservative state Sen. Thomas Van Meter. The repeal failed, 56-44.In 1984, for the first time, state income-tax collections surpassed sales-tax collections. By 2005, income-tax revenues accounted for nearly half of all state revenues, far outpacing the sales tax.Since then, the tide has run in the other direction. Under Govs. Bob Taft (1999-2007) and Kasich (2011-present), state income-tax rates have been slashed 30 percent. Sales-tax collections now far outpace income-tax revenues.

Kasich hopes to accelerate that trend, proposing a 17 percent reduction in income taxes, offset by increasing the sales tax to 6.25 percent, from 5.75 percent.

But even with Republican supermajorities in the House and Senate, Kasich might find a shortage of fellow ax wielders. Over time, the income tax comes in handy.

This piece originally ran in the Columbus Dispatch on Wednesday February 15, 2017

Columbus native Michael F. Curtin was formerly a Democratic Representative (2012-2016) from the 17th Ohio House District (west and south sides of Columbus). He had a 38-year journalism career with the Columbus Dispatch, most devoted to coverage of local and state government and politics. Mr. Curtin is author of The Ohio Politics Almanac, first and second editions (KSU Press). Finally, he is a licensed umpire, Ohio High School Athletic Association (baseball and fastpitch softball).

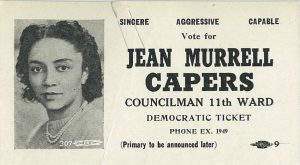

1948 photo (CSU)

Jean Murrell Capers by Marian Morton

Jean Murrell Capers (1913-2017) met head-on the challenges of being both female and black by maintaining her outspoken political independence. The daughter of teachers, she went to Western Reserve University on a scholarship, one of the university’s few black students at the time. She earned a degree in education and taught briefly before getting her law degree from Cleveland Law School. She passed the Ohio Bar in 1945 and was appointed assistant police prosecutor by Mayor Thomas A. Burke in 1946. “[A]nother first for Negro women,” the Cleveland Call and Post announced proudly. [16]The newspaper later applauded Capers as the one of several “lady lawyers [who] bring beauty [and] brains” to the local legal community. An accompanying photo shows a stylish Capers, smiling mischievously. [17]

Capers made her first foray into partisan politics in 1943, staging an unsuccessful write-in campaign for City Council. She also ran unsuccessfully for Council in 1945 and 1947. Like Cermak, she early gained the support of organized women’s groups, and in 1949, she got one of her few political endorsements from the Glenara Temple of Elks, of which she was a member. “[I]t is high time that Negro womanhood took its place in the sun of city politics,” said Republican leader and temple member, Lethia C. Fleming. [18] In 1949, on her fourth try, Capers became the first black woman to be elected to City Council and the first Democrat to be elected from what had historically been a Republican ward.

Her four subsequent elections to Council reflected her ability to organize her ward and get out her supporters, doubtless impressed by her education, her political skills, and her glamorous appearance. Capers fought for a swimming pool for her ward’s children and offered a prize for the neighborhood’s cleanest yard.

But she also sparked plenty of controversy and made plenty of enemies. She joined forces with Council member Charles V. Carr in an unsuccessful effort to make the possession (as opposed to the sale) of policy slips legal despite police efforts to crack down on the numbers racket. [19] And despite the opposition from local pastors, she got a license for a local bingo parlor. She criticized Cleveland’s ambitious slum clearance program: “In every instance since urban renewal began, the city has created more problems than it has cured. This is reflected in increased crime and lower sanitation standards.”[20] (Its critics often referred to urban renewal as “Negro removal.”)

Her opponents alleged that she had ties to rackets figures and pointed to her poor attendance record at Council meetings. There were also allegations of voter fraud in her ward in 1952 and 1953. In 1956, she was the only black member of Council to oppose the fluoridation of city water, further estranging her from the Democratic majority. [21]

Even though it had earlier praised her, Capers’ most outspoken critic became the Cleveland Call and Post, the city’s African-American and Republican newspaper, which accused her of being a lazy Councilman and a “wholly irresponsible person.” [22] She was a “vicious, skilled campaigner,” the paper claimed, whose sex “protected her from retaliation in kind.”[23] Her sex did not protect her from savage attacks by the paper – for example, for her opposition to the appointment of Charles P. Lucas, a black, to the Cleveland Transit Board in 1958: “the odor of selfish irresponsibility and putrid demagoguery … marked the conduct of Mrs. Jean Murrell Capers,” the paper spluttered. [24] Everyone wanted her out of office except her constituents.

By 1959, however, although she was chairman of Council’s powerful planning committee, Capers had lost her Council seat to James H. Bell, the candidate endorsed by local Democrats. Bell “ has retired, at least temporarily, one of Cleveland’s most colorful and successful political demagogues …. [who] was possessed of a vibrant sort of feminine attractiveness, an excellent family background, and a razor sharp mind, ” wrote the Call and Post. [25] Capers unsuccessfully filed suit in Common Pleas Court to set aside Bell’s “fraudulent victory.” [26] Undiscouraged, she ran unsuccessfully in 1960 in the Democratic primary for state Senate in a large field that included Carl Stokes, and in 1963, she lost a primary race for her old Council seat.

In 1965, Capers and her League of Non-Partisan Voters organized the movement to draft Stokes to run as an independent mayoral candidate, a race which he lost. Only two years later, however, the league supported Republican Seth Taft when he ran against Stokes for mayor. Capers minced no words when she explained league’s about-face: “Mr. Taft has qualities superior to those of his opponent and has the broad personal knowledge necessary to administer the complex affairs of the city. Stokes knows nothing about anything and is far too superficial in our judgement to serve as mayor. Carl Stokes especially lacks the knowledge and understanding necessary to solve this city’s crisis in human relations.” [27] Capers subsequently acted as the lawyer for Lee-Seville homeowners who fought off Stokes’ plan to locate public housing in their neighborhood. In his embittered autobiography, Stokes called her “one of the brightest politicians ever to come out of Cleveland” but also accused her of being a hustler who supported him in 1965 only to get herself back into politics. [28]

In March 1971, Capers decided to run as an independent in the mayoral primary. She had joined the new National Organization for Women and hoped to win support from the emerging woman’s movement. In mid-summer, she discovered that she had missed the Board of Elections filing date for independents but persuaded a federal judge to overturn this early filing date. The date became a moot point since she did not get enough valid signatures on her petition and was disqualified from the mayoral race. Thanks to a divided Democratic Party, Republican Ralph Perk was elected mayor.

By 1976, Capers had become a Republican herself, and her former nemesis, the Call and Post, endorsed her candidacy for Juvenile Court Judge. She lost this race, but Republican Governor James A. Rhodes appointed her to a municipal judgeship in 1977, a position she held until her retirement in 1986. Reflecting on her long, difficult political career, Capers pointed to her double handicaps of race and gender, maintaining that her “detractors resented her not just because she was a black woman but because she was an educated black woman. ‘They still had the concept that the only place for a Negro woman was on her knees scrubbing the floors. If I had been a dumb Negro woman, I would have gotten along much better.’”[29]

In recognition of her long, difficult political career, Capers earned many professional honors. These include the Norman S. Minor Bar Association Trailblazer Award and induction into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame.

This essay is part of a longer piece written by Dr. Marian Morton, here