Reprinted by permission

Original link is here

Editorial: Ohio Constitution deserves bipartisan review

Columbus Dispatch 3/23/2107

Thursday Posted Mar 23, 2017 at 12:01 AMUpdated at 6:27 AM

State lawmakers should grant a reprieve to the Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission. The 32-member body, diligent but underappreciated, is set to expire prematurely at the end of this year.

The unapologetic executioner is state Rep. Keith Faber, R-Celina, who — as Senate president last session — slipped a poison pill into the state budget to kill the commission.

Now that Faber again is a House freshman, House Speaker Cliff Rosenberger and Senate President Larry Obhof have an opportunity to redress Faber’s petulance, show prudence, and allow the commission to fulfill its original promise.

Under the leadership of former Speaker William G. Batchelder, the commission began in October 2011. It was given a decade to work, to expire July 1, 2021.

The Ohio Constitution deserves a periodic, methodical and bipartisan review, which is what has been occurring since the commission got rolling in 2014.

The late start was largely attributable to Faber’s reluctance to help get commissioners appointed and staff hired.

The constitution, 166 years old, is the nation’s sixth oldest. At nearly 57,000 words, it’s the 10th longest. With such age and length comes obsolete provisions and archaic constructions.

Because the state is not likely to hold another state constitutional convention in the foreseeable future (the last was in 1912), a bipartisan commission of respected individuals should be impaneled once every two decades to examine potential amendments for a public vote.

Since 2014, the commission has performed valuable service. It paved the way for two amendments approved by Ohio voters in November 2015, providing for apportionment reform and anti-monopoly safeguards.

Near the end of last year, the commission sent to the General Assembly proposals to eliminate several obsolete sections of the constitution. If sent to the ballot and approved by voters, they would eliminate:

‒ Courts of conciliation, created in 1851 to allow resolution of disputes outside the traditional legal process. They’ve never been used, and long ago were replaced by modern arbitration proceedings.

‒ The Supreme Court Commission, created in 1875 to relieve backlogs of cases. It has not been used since 1885.

‒ Sections authorizing specific debt and bonding authority for projects long ago accomplished with debts long ago paid off.

‒ Provisions on the Sinking Fund Commission, whose responsibilities long ago were taken over by the state treasurer.

Like the legislature itself, the commission works through standing committees, which hear testimony and compile research. The commission’s body of research, available on its website, is a model of objective, detailed analysis — a treasure for researchers and policymakers.

The commission has not yet dived into the constitution’s sections on the executive branch, the elective franchise, the militia, and a few other areas.

One of its committees is attempting to find compromise on an amendment that would make it easier for voters to enact initiated laws, but more difficult to enact initiated amendments.

This is highly sensitive territory, requiring bipartisan diplomacy and outreach to a broad spectrum of interest groups.

Since 1912, the Ohio Constitution has given voters the power to directly initiate constitutional amendments, bypassing the General Assembly. Ohio is one of only 16 states with that provision, and one of only 11 where enactment requires only a simple majority vote.

The committee has discussed requiring a 55 percent vote to amend the constitution. This deserves patient, extensive review. Pulling the plug on the commission sends the opposite message — one of callous indifference.

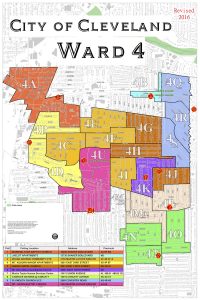

Cleveland Council Forums – August 2017

Cleveland Council Forums – August 2017