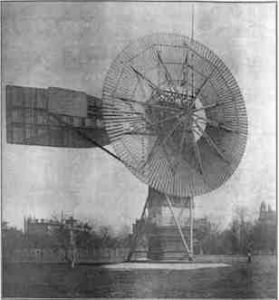

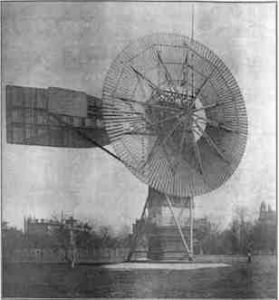

Charles Brush home on Euclid Avenue and His Windmill (Library of Congress)

The pdf is here

A Time of Transition and Challenge: Cleveland in the Gilded Age

Prologue: Innocents Abroad

by Dr. John Gabowski

The five months between June and November 1867 were one of the high points in the lives of Emily and Solon Severance of Cleveland. They, along with six other Clevelanders were part of a group of seventy-five who traveled to the Holy Land aboard the ship Quaker City. One of their fellow passengers was Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name as Mark Twain. Clemens would become a close friend of the Severances and immortalize their trip in his book Innocents Abroad published 1n 1869.[i]

While that volume chronicled an adventure that became part of the Severance’s lives, a subsequent work by Clemens would give the name to the period in which they matured and prospered. The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, written jointly by Clemens and Charles Warner in 1873 was a biting satire of a nation whose focus had, in the years just after the Civil War, turned to the accumulation and display of wealth to a degree where it was a detriment to individual and national character. More importantly, the book title became the name of a distinct period of United States history and area of historical studies, which focuses on the years from 1870 to the turn of the twentieth century. It was a period in which enormous industrial and urban growth challenged the verities of American democracy. The rise of great individual fortunes raised concerns about the divisions of class in a supposed classless society, but at the same time served as an example of opportunity. One of the most popular books or the era, Acres of Diamonds by Baptist minister Russell Conwell in 1890 encouraged visions of individual opportunity. Conversely, the invention of new systems of industrial management and control, including monopolies and trusts during the Gilded Age, acted as barriers to individual initiatives and stymied opportunity. Yet, they hinted at more rational and inexpensive ways of producing goods. Perhaps most of all, the visual manifestations of wealth epitomized by grand houses, estates, and examples of conspicuous consumption were hugely publicized and envied. But many saw them merely as gilding on a society that was becoming increasingly divided by income and class as well as by an evolving ethos that seemed to lack a humane moral core.

Certainly, the Severances, whose lives did not come to epitomize the excesses of the period, saw the Gilded Age’s effects in their hometown. The Cleveland into which Solon (1834) was born was small (a population of 1075 in 1830 and 6,071 in 1840), rather homogeneous, and primarily mercantile. His wife, Emily, had been born in Kinsman, Ohio, and had come to Cleveland in the 1850s. When they disembarked from the Quaker City they returned to a city with over 70,000 inhabitants, most of whom were recent arrivals and nearly half of whom were of foreign birth.[ii] More importantly, they returned to a city made prosperous by the recent Civil War and rapidly gaining more wealth through a variety of new and expanding industrial enterprises. As they lived out their lives during the coming decades they observed a city transformed but also challenged by the creation of great fortunes and the temptations of easy wealth; the inadequacies of existing political systems; and the polarization of capital and labor. Having seen the Holy Land, they were now to witness a city undergoing its “urban adolescence.”

The Fortunes of War

Often lost in the popular understanding of the Civil War is the role that conflict had in making some in the victorious North immensely wealthy. Like other major conflicts that followed, government spending for the implements and accoutrements of battle spurred industrial innovation and production — and the interest paid on the government bonds issued to fund that spending proved an added bonus to investors — at least to those on the victorious side. It was the Civil War that propelled Cleveland into its industrial age and its version of the Gilded Age.[iii]

This is not to say that the city’s industrial period began in 1861. Rather the fact that it was developing an industrial infrastructure in the years before the War served to allow it to turn those assets to the needs of conflict. Several examples are particularly salient.

By the beginning of the War Cleveland was already a railroad hub, with tracks reaching west to Chicago, southwest to Cincinnati, southeast to Pittsburgh and east to New York. Clevelanders, such as Amasa Stone and John H. Devereux, who had built and invested in the roads emanating from the city, prospered, as did local bond and stock holders for the lines, with wartime demands for traffic. During the War Devereux, holding the rank of General, served as the superintendent for US Military Railroads in Virginia.

This activity had consequences for local industry allied with the rail industry. The Cleveland Rolling Mills, established by John and David Jones in 1857, initially prospered by re-rolling worn iron rails for the growing railroad network in Ohio, a need which only increased during the war at which time Scottish immigrant, Henry Chisholm, who had joined the Jones in 1857, became the manager of the mills. After the War he was one of the area’s wealthiest men.

The central role of rail transport during the War was complemented by the telegraph and here too Cleveland benefited because Jeptha Homer Wade, one of the founders of Western Union, had taken up residence in the city in the 1850s. The wires of Western Union were key to coordinating troop movements by rail, bringing news of the conflict to the public and allowing President Lincoln a real-time connection to events taking place on battlefields.

If any Clevelander was to become a symbol for the wealth of the Gilded Age, it was John D. Rockefeller and here too, the Civil War was critical. Rockefeller and his commission house partner, Maurice Clark saw their profits for the sale of grain, meat, and produce rise from $4,000 in 1860 to $17,000 at the end of 1861, a time when the government was their primary customer.[iv]

It is impossible to ascertain how the profits made by these individuals and others were used during and after the war. One possibility is investment in government bonds issued to finance the conflict. Bonds paying 6% interest and maturing in 20 years could be purchased for as little as $50.00 (still a considerable sum, given that a private in the Union Army earned but $13 per month[v]). But the bonds had attractions for those who could afford them. They could be purchased with the greenback paper currency issued during the conflict but the interest was payable in gold. Jay Cooke, a financier born in Sandusky, conceived and carried out the sales — $500,000,000 worth of bonds were sold. If all went to maturity, investors would have realized $30,000,000 sometime in the 1880s. How much of this came to finance Cleveland’s Gilded Age cannot clearly be determined.[vi]

Profit and good investments were not the only good fortune that came to Cleveland and northeastern Ohio because of the Civil War. They were complemented by enduring political relations that would link Cleveland intimately to national politics and policy for the next four decades. The city’s strong backing of Lincoln, and the state’s role as one of the major contributors to the conflict did not go unnoticed during or after the War. But there were more intimate links that would be beneficial during and afterwards . While Jay Cooke of Sandusky sold bonds to fund the Union cause, Salmon Chase of Cincinnati served as Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury. After the war four Ohioans who had served in the Union Army, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and William McKinley, occupied the Presidency. For sixteen years in the Gilded Age, Cleveland and Ohio had a friend in the White House . Yet, there was a cost to this. Ten thousand men (two thirds of the eligible population) from Cuyahoga County served : 1,700 died in the war and another 2,000 left service wounded or disabled. Victory and sacrifice were powerful talismans in Gilded Age Cleveland.[vii]

Urban Adolescence

Perhaps the best available study of Cleveland during the Gilded Age is James Beaumont Whipple’s “Cleveland in Conflict: A Study in Urban Adolescence, 1876-1900” which was completed at Western Reserve University in 1951.[viii] Very much a linear and non-interpretive study of the city, the dissertation’s equating of Cleveland’s Gilded Age with adolescence is truly apt. The city grew rapidly during the period, but was largely absent of any true control or full understanding of the changes it was experiencing.

Numbers provide a sense of scale for the change. In 1870 Cleveland’s population stood at 92,829. A decade later it was 160,146. By 1890 it had risen to 261,353 and by century’s end it stood at 381,786 making it the seventh largest city in the nation.[ix]

Those increases came about largely by in-migration both from Europe and the surrounding countryside, but also because of the physical expansion of the city. Annexation of neighboring communities and townships such as Newburgh, Glennville, Linndale and East Cleveland, in part or whole, increased the size of the city from 7.325 square miles in 1860 to 34.34 square miles at the beginning of the new century.[x] Essentially, in terms of both population and physical size Cleveland had expanded by a four plus factor in the last four decades of the nineteenth century.

The expansion was driven by the city’s industrial economic potential which hinged on its centrality to markets in the east and the expansion of settlement in the west of the United States; its rail and water transport systems; and its access to abundant natural resources such as coal, iron ore, crude oil, timber, clay, and limestone. It was a perfect place to be for those imbued the get-ahead, get rich attitude of the Gilded Age as well as for tens of thousands of job seekers in what was rapidly becoming a highly mobile global labor proletariat.

Its industrial base expanded far beyond the iron manufacturers of Civil War and pre-war era. By the 1870s, oil refining was the major industrial endeavor in the city while iron and steel came second. Those two core industries spun off ancillary enterprises — chemicals and then paint and varnishes derived followed from oil refining. Iron and steel catalyzed both a shipbuilding industry to produce vessels to carry iron ore and other commodities, as well as the production of devices such as the Brown-Hoist and Hulletts to unload ships carrying bulk commodities. Products manufactured from iron and steel included everything from fasteners to sewing machines as well as jail cells, park benches, carriage hardware, and a wide variety of forged, molded, and machined products. An expanding precision-based machine tool industry created the devices that created products from steel. The city also became a site for what are now termed “disruptive technologies” which challenged existing ways of providing power and producing goods. The most disruptive was, perhaps, electricity which was to provide a source of power that along with internal combustion, would end the age of steam. The companies that emerged from this era included Standard Oil, Sherwin-Williams, Glidden, Grasselli Chemical, Otis Steel, Warner and Swasey, American Shipbuilding, Wellman-Seaver Morgan, White Sewing Machine (and later White Motors), Van Dorn Iron, and Brush Electric, and iron ore “houses” such as Oglebay-Norton, Pickands Mather, and Cleveland Cliffs. Together they and other local industries would increase the value of manufactured goods in Cleveland from $27,049,012 in 1870 to $139,849,806 in 1900 while wage-based employment in the city rose from 10,063 to 58,810.[xi]

Seeing Wealth

The most visible symbol of achievement outside of the growing factory districts and the increasing pollution of the city’s air and water was Euclid Avenue where many of the city’s wealthy lived. Initially, known as the Buffalo Road, the street became a desired place of residence in the 1850s when wealthy merchants such as Williamsons, Binghams, Perrys, and others built substantial but not terribly ostentatious homes, along the avenue in the open lands east of Public Square. During the Gilded Age the number and size of homes along Euclid increased geometrically. Within four decades Euclid was lined with homes from what is now Playhouse Square to University Circle with the beginning of the street east of the Square given over by 1900 to the commerce that came in the wake of growth and expansion. The homes, particularly those sited on the north of the street, were outsized showplaces of wealth and power with lots that stretched north from Euclid to what is now Perkins Avenue in the section of the avenue between what is now E. 30th Street and East 55th. It was, to use the title of Jan Cigliano’s seminal history of the street, a “Showplace of America,” indeed one which was listed as a must-see attraction in Baedeker’s guide to the United States.[xii]

The enduring popular local mythology of the street tends to see it as the home of Cleveland’s establishment. But that view neglects the fact that a number of the residents were relative newcomers to the city as well as to wealth, and that it was their progeny who would become “establishment.” The street was, more correctly, a combination of older families whose prosperity dated from the 1830s, early industrialists and railroad entrepreneurs from the 1850s, and post-Civil War industrialists and businessmen. It was neither predominantly nouveau-riche or “old shoe,” but nevertheless its halcyon period was of the Gilded Age. Families like the Mathers , Paynes, Worthingtons, and Severances had histories in the city dating to before the Civil War and would eventually build homes on the Avenue, but others such as railroad builders Henry Devereux and Amasa Stone, whose daughter Flora would marry into the Mather family, were first-generation Clevelanders. This was also the case with Jeptha Wade, Henry Chisholm, and Sylvester Everett as well as John D. Rockefeller, whose house on the street did not fit the now mythical image of the man who owned it.

Rockefeller’s home stood at the southwest corner of Euclid and what is now E. 40th street — it was on the less desirable south side and while substantial it paled in comparison to the two Wade homes that stood across Euclid directly to the north and particularly in comparison to the huge home constructed by banker Sylvester Everett, diagonally across from the Rockefeller House. Nevertheless, Rockefeller’s Gilded Age career made marks on other parts of the street because those who partnered with him in establishing Standard Oil became immensely wealthy.

The creation and rise of Standard Oil is a textbook example of business and wealth in the Gilded Age, one which has its roots in Cleveland. In 1863 Rockefeller, along with many other Clevelanders, became interested in petroleum as a commodity — one which could be refined into kerosene and paraffin for lighting. Cleveland’s direct rail connection with the Pennsylvania oil fields made it an ideal center for dealing in the new commodity. Rockefeller’s consolidation of the industry — viewed both as rapacious and farsighted; his creation of a perfect example of a vertically-integrated company; and his creation of the modern trust have come to epitomize Gilded Age business practice. Those who joined with Rockefeller, including Clevelanders Harry Payne, Steven Harkness (who moved to the city), and Louis Severance became immensely wealthy because of that association. Another early partner, Samuel Andrews, an English immigrant who was Rockefeller’s “chemist,” also became wealthy and could have, had he remained a partner in the firm, become even wealthier. It was his Standard Oil fortune that financed perhaps the most spectacular home on Euclid.[xiii]

Andrews cashed out of Standard Oil in 1874 and began the construction of his home on Euclid (at the northeast corner of what is now E. 30th) in 1882. Completed three years later the house was immense; so much so that in a short period of time it proved to be unmanageable. Andrews lived there for only several years. His son Horace would later use the house periodically, but it stood largely vacant until demolished in 1923. It was and remains somewhat of a metaphor for the excesses of the Gilded Age.

Underneath the Gilding

Ironically, the years that bookend the construction period — 1882-1885 — of the Andrews House also mark two of the most noted local labor actions in Cleveland during the Gilded Age. And those strikes, in their turn, also relate to the immense fiscal instability of the era, for the period 1882-1885 marked one of the frequent economic recessions in the United States, one in which business contracted nearly 33%. While these contractions diminished or destroyed great fortunes their greatest impact was on the wage laborers in the industries of the age. In bad times wages were cut and workers released — released into a system that had no real social safety net outside of church and neighborhood-based charity and, in the hardest times, a modicum of “poor relief” from municipal governments.

In May 1881 Henry Chisholm the head of the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company died. A hands-on, shop-floor manager, he was beloved by his workers. Together they gathered funds to build his memorial in Lake View Cemetery. The following year the country entered into recession as railroad building waned. With the demand for iron and steel down, William Chisholm, Henry’s son and the then head of the Rolling Mill refused workers’ demands for a closed shop for members of the Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers and a voice in setting wage scales. A strike ensued, one marked by violence as immigrant Polish and Czech strikebreakers were brought into the mill. The strike failed, but three years later those who had been strikebreakers went on strike because of another wage cut. It was violent, with strikers marching downtown from the mill neighborhood near Broadway and Harvard. Some carried the flags of socialism and anarchy. The “mob” forcibly closed other factories allied with the ownership of the Rolling Mills in order to cut off the owners’ sources of income. The violence of the strike made the national news and was depicted pictorially in Leslie’s Weekly.[xiv]

It was not the first, nor the last major labor action in Cleveland during the Gilded Age, a period both locally and nationally where the rights of workers in an evolving wage-labor economy were set against the perceived rights and substantial powers of owners, businesses, and monopolies. It was a time of not only dissention, but of fear.

Those fears came fully to the fore nationally during the great railroad strike of 1877. Its origins stemmed from deflation and wage cuts which followed the Panic of 1873 which was initiated by the collapse of Jay Cooke and Company. The Ohioan Cooke had been the genius of the Civil War bond promotion, but the panic proved his undoing. His banking house (perhaps the most noted in the nation) overspent its capital in promoting the development of the Northern Pacific Railroad. That, in turn triggered a fiscal crisis that lasted the better part of a decade and created an era of wage contraction. A series of wage cuts by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and then other lines sparked violent strikes which spread across the nation. Nationally, over one hundred people were killed in confrontations between police militias and workers. In Pittsburgh, shootings of workers led to the burning of the yards, depot and other properties of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The strike lasted forty-five days.

Cleveland, although a rail center, managed to escape the violence of the strike. Nevertheless, the national news added to local angst and fear which had initially been sparked by a coopers strike at Rockefeller’s Standard Oil works in April of the same year. Led, in part, by a Czech immigrant socialists Leopold Palda and Frank Skarda, the strikers, many of whom were immigrants themselves, also called for a general strike in the city, inviting all workers making less than a dollar a day to join them. The general strike didn’t take place, but that demand, and the railroad strike that followed created a fear of class warfare in the city and increased suspicions about the growing immigrant population. Memories of the Paris Commune of 1870 were not uncommon in American cities such a Cleveland during the labor unrest during the nation’s Centennial decade.[xv]

Those fears led to reflexive actions. In October 1877 a group of prominent Clevelanders organized an independent military unit, Troop A, to serve as a bulwark against possible labor violence. The following year leading citizens created the Cleveland Gatling Gun Battery. The Battery built an armory, complete with loopholes, on Carnegie Avenue as a last bastion defense against labor violence. Both organizations would evolve into social organizations for their members, and Troop A eventually became part of what would be the National Guard. With a more egalitarian membership it served in both World Wars. Both, however, did see “action” in several strikes including the Rolling Mill strike of 1885 and the streetcar strike in 1899.[xvi]

The angst of the era also found its way into a novel which would become a best seller in 1884. Published anonymously in 1883, The Breadwinners was a melodramatic but message-laden saga set in the mythical town of Buffland in which the wealthy residents of equally mythical Algonquin Avenue successfully fight off socialist labor unrest. Buffland was the pseudonym for Cleveland and Algonquin was a stand-in for Euclid Avenue. The author turned out to be John Hay, former secretary to Abraham Lincoln, son-in-law to Amasa Stone, and a resident, at the time, of Euclid Avenue. His views on the rights of labor were colored both by his own elitism and fears. They were not only clearly expressed in the novel, but in his personal communications as well.[xvii]

Contention between capital and labor continued through most of the Gilded Age in Cleveland, but the city managed to avoid events that paralleled in scale Chicago’s Haymarket Riot of 1886 and the Homestead Strike of 1892. Strikes continued on a smaller scale. In 1896 workers at the Brown Hoist Company took to the streets when their request for a nine-hour day (they worked a ten and a half holiday shift on Saturdays) and the reinstatement of several dismissed workers was met by a lockout by the management. [xviii] Three years later the city’s streetcar network came to a virtual halt during a labor action focused on better wages and working conditions. It turned violent and the state militia, as well as Troop A were called out to restore order.

One of the other issues in the streetcar strike was the recognition of their union. That was not achieved, but overall, the Gilded Age saw the growth of unions, mostly representing the crafts and trades, in the city. The Knights of Labor formed fifty assemblies in the city which encompassed both skilled and unskilled workers. The American Federation of Labor created the Cleveland Central Labor Union to compete with the Knights and established 26 locals between 1887 and 1891. In 1891, Max Hayes who came to epitomize the cause of labor in the city began, along with Henry Long, publishing The Cleveland Citizen. Moderately socialist in outlook and largely focused on skilled trades, the Citizen would go on to become the nation’s oldest labor newspaper. By century’s end the city had 100 labor unions as well as branches of the Socialist Labor Party which argued for a rearrangement of the entire economic system, a prospect which was seen as alien and a threat to private property. [xix] While Socialism never achieved a strong foothold in Cleveland it was a constant political undercurrent during the Gilded Age and into the early twentieth century. National party candidates such as Eugene Debs and local candidates like Charles Ruthenberg polled well — well enough to be perceived as a threat to American ideals and government, particularly at the municipal level in industrial cities like Cleveland.

Trying to Govern Growth

Cleveland entered the Gilded Age with a city government structure dictated by the state and which perhaps would have functioned reasonably well in a small city. The General Municipal Corporation Act of 1852 essentially reduced the mayor to a figurehead with no real authority over a ward-based city council and more importantly, placed much decision making and spending power in the hands of the council and a series of administrative boards and commissions. The act also made previously appointive positions, such as the commissioner of waterworks and the police judge elective. Essentially, this created a system lacking in strong central direction and peppered with smaller power centers in the council and boards.

Cleveland’s leadership within this system echoed its New England ethos. The “best” citizens undertook civic duties as expected. Cleveland’s mayors during the period from 1870 to 1890 included Frederick W. Pelton (1870-1873), a banker; Charles Otis (1873-1874) head of Otis Steel; Nathan Perry Payne (1875-1876) coal merchant; William G. Rose (1877-1878, 1891-1892) a refiner and real estate investor who was independently wealthy by age 45; “Honest” John Farley (1883-1885, 1899-1901) a contractor, investor, and banker; Brenton D. Babcock (1887-1888) a coal merchant; and George Gardner (1885-1886, 1889-1890) commission house broker and banker. Many of these men had also served as council representatives or on some of the boards and commissions that truly wielded power in the Gilded Age city.[xx] One of the most noted figures to come out of Gilded Age Cleveland, Myron T. Herrick, began his political career as a city councilman (1885-1890) in Cleveland and would then go on to become governor of Ohio (1903-1905) and eventually ambassador to France (1912-1914, 1921-1929). Herrick’s political career was engendered largely by Marcus Hanna whose entry into politics was as an organizer at the ward level.

Despite the figurehead status of the mayor, two managed to navigate the city through its labor troubles. Rose played an important role in seeking accommodation between the owners and workers during the railroad strike of 1877 and Gardner ordered William Chisholm to restore wage cuts in order to end the 1885 Rolling Mill Strike, but only after threatening to use artillery against the strikers. But, others recognized the frustrations of the office. Otis and Payne refused second terms so they could return to manage their businesses and Babcock argued for moving to a Federal system in which the mayor would have true authority to work with council representatives in governing. That would occur in 1892 when, after four years of effort, the city’s leading citizens convinced Columbus to approve the change.

Even with the change the effort to deal with the urban infrastructure necessary to support the growth and gilt of Gilded Age Cleveland was an enormous task. Mayor Rensselaer Herrick gave some sense of that in 1881 when he commented that the Cuyahoga River was an “open sewer” running through the city[xxi]. On a bad day the residents of Euclid Avenue could easily sense the origins of their good fortune when lake winds blew the smoke from the Otis Steel mill on the lakeside at E. 33rd Street their way — the fact that many of the stone mansions turned black so quickly testified to the environmental degradation created during unregulated expansion during the era. Once known as the Forest City, Cleveland began to lose many of its trees to pollution during the era. The solution was to plant more resistant species such as sycamores. Over and over again, arguments against air pollution in the coal-powered city were seen as anti-growth. How could Cleveland compete with Pittsburgh if it hamstrung its industries with fines and regulations?

As the city grew in population and size the task of creating infrastructure became enormous. By 1880 Cleveland had over 1,200 roads, streets, lanes, alleys and “places,” many of which remained unpaved. Wood block streets had to be replaced with stone and stone eventually gave way to brick. But even by 1889, when the street network totaled 440 miles, less than two miles per year were being paved with brick. Similar needs related to expanding the water and sewer system, a project compounded by the need to continually construct water intakes further into the lake to find water unpolluted by industrial and human waste. [xxii]

Similarly, the increase in population dictated other changes. In 1866 the public schools enrolled 9,270 children. By 1900 the enrollment had risen to 58,105, but that number represented only 54.5 percent of the school age population.[xxiii] While the city had done reasonably well in erecting new school buildings it, like many other cities, found it difficult to foster education in an economy where the income of working children formed an important part of many family budgets. The need for family income often trumped an education beyond the elementary level.

As the city grew it became both an employer and more importantly the source of lucrative municipal contracts to create and maintain its expanding

infrastructure. In 1876 the city’s annual budget totaled slightly under $625,000. Nine years later it was over $3,000,000 and at the turn-of-the-

century, just below $7,000,000. By 1885 the municipal payroll was over $99,000 per month. Contractors found the city to be an excellent customer and made money by providing services ranging from the removal of nightsoil to street paving.[xxiv] The amount of money flowing through city hall was tempting. In 1886 treasurer Thomas Axworthy suddenly disappeared. He had fled to Canada after using public funds to make a series of private loans. The loss totaled over $500,000. His whereabouts were revealed in a letter he sent to the mayor some days after he vanished. He closed the letter as follows: “Good bye and God Bless Cleveland”.[xxv]

Perhaps the most valuable municipal “investments” of the era were the franchises awarded to private companies for running street railways and providing new modern utilities such as gas or electricity to residents and businesses. In many Gilded Age cities, such as New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati, this process became a sort of “largess” (or to use the then contemporary term, “boodle”) distributed by a political machine, such as Tammany Hall in New York or Boss Cox in Cincinnati, in return for bribes, votes, or other favors. Cleveland lacked a true urban political machine of the Tammany type during this period. Ironically, it would develop a nascent one when it achieved a Federal structure of governance in 1892. The election of Robert E. McKisson as mayor with true authority and power in 1895 gave the city its first boss. By buying immigrant votes and rewarding” loyal” workers and councilmen, the “boy mayor” began to build an empire. He persisted despite the protests of good government organizations which represented evolving Progressive ideas of municipal management, but he came to grief when he challenged another type of boss, Mark Hanna, for a US Senatorial seat. Hanna won by a whisker and used his power as a national Republican kingmaker, along with pressure from the good governance groups, to ensure McKisson’s defeat in 1899.[xxvi]

Hanna knew the Gilded Age system better, perhaps, than any other local political leader and was able to manipulate it better than others because of his growing wealth. That wealth and personal acumen, along with Cleveland and Ohio’s close connections to Washington, allowed him to become one of the power brokers of the era. Although not a resident of Euclid Avenue (he was a west-sider, his home was in Clifton Park) Hanna had a profile similar to many of those who lived on the Avenue. He had been born in New Lisbon, Ohio, and came to Cleveland with his family in 1852 at the age of 15. After attending Central High school and a brief stint at Western Reserve College (then in Hudson) he worked at his parents’ wholesale grocery business. When he married he joined his in-law’s (the Rhodes) iron and coal business — commodities that built a number of local Gilded Age fortunes. He became head of the business in 1885 when his father-in-law died. The company, renamed M. A. Hanna and Company, which was run in conjunction with his brothers, provided him with the funds he needed to indulge in a prominent Gilded Age endeavor, political organizing.

Hanna’s political activities and his connections to the Republican monied elite in Cleveland and, later, in Ohio, and then nationally, helped him make Joseph Foraker governor in 1885; John Sherman a US Senator in 1892; and William McKinley President in 1896. After dispensing with Boy Mayor Robert McKisson’s challenge, he won appointment to the US Senate in 1897.[xxvii]

But there was another aspect of Hanna’s life that fit more neatly into the Gilded Age. Before he became the head of M. A. Hanna, he dabbled in street railways. While his political mechanizations of are integral and well recognized parts of Cleveland’s Gilded Age story his streetcar ventures are, perhaps, of more consequence in understanding the intersection between it and the city’s Progressive era. Hanna, like other entrepreneurs around the nation, understood that urban transportation in the expanding industrial metropolises of the US had a huge potential for profit. In the pre-automotive age the equation was simple — the end of the walking city dictated that people of almost all strata needed an easy way to get around town. Street railways, first horse-drawn and then electric, had a large clientele which needed to get from home to office or home to factory five and six days a week. To operate such a system one needed only to build it, but one could only build it after getting a franchise from the city government. That process, which was based on bids, could also involve bribes and other political power plays.

In 1879 Hanna, along with business partner Elias Simms, found himself bidding against a newcomer in the local franchise contests. Born to a wealthy family in Kentucky, Tom L. Johnson had run successful street railway franchises in Indianapolis and Detroit, Brooklyn, and St. Louis. Cleveland was his next target, but he lost the competition for a franchise (despite a low bid) to Simms-Hanna because of a technicality. No one really knows what role bribery may have played in the contest, but savvy local businessman courted local council men. Elias Simms once noted that all that local councilmen wanted was money and added that he constantly had to have his pocketbook at hand.[xxviii]

The Hanna-Johnson battle went on for three years in what has come to be called the Cleveland Railway Fight. Johnson eventually bested Hanna. The contest, however, brought him to Cleveland in 1879 where he later took up residence on Euclid Avenue. As a wealthy newcomer to the city and an entrepreneur of note, he was a perfect addition to the glitter of the Gilded Age, but though of the same class he and Hanna had no love for one another.

That animosity would spill over into their political views which were colored by their somewhat contrary personal visions of society. Johnson had a conversion experience. Inspired by the writings of Henry George, he went from an entrepreneurial plutocrat to a social reformer and anti-monopolist. He used his fortune to engineer a political career, first as a Democratic representative to Congress and later as a four-term mayor of Cleveland. He fully engaged himself in what he defined as “…the struggle of the people against Privilege.” [xxix] Gilded Age Johnson morphed into one of the most significant figures of the American Progressive era.

Hanna remained firmly locked into the mainstream of the Republican Party. He was part of the monied class in Cleveland who strongly opposed Johnson and who were particularly troubled by his advocacy of the municipal ownership of utilities, such as streetcars and the evolving electrical grid. It seemed to border on Socialism. When Myron T. Herrick, a close friend, whose career was closely linked to Hanna’s power ran against Johnson in the gubernatorial race of 1903, Hanna could easily cherish that triumph. The joy was short-lived. Hanna died early the next year and Herrick turned out to be a one-termer.

Despite the gulf that separated them, Hanna and Johnson shared one important desire — that was to find a way out of the chaos and contention of the Gilded Age. Albeit conservative, Hanna was seeking some accommodation between labor and capital in the latter part of his career. Absent that accommodation, the American system would remain open to the challenges of “foreign” systems of government and societal organization. Johnson, an astute businessman, also realized that the “system” was not working and that societal divisions were dangerous and damaging to society. His solution was to create a more complete and informed democracy and to expand and professionalize the responsibilities and management of government. His long-standing battle for municipal ownership of utilities may have echoed the demands of Leopold Palda, Charles Ruthenberg, and other area socialists, but it represented a vision of efficiency — efficiency that would lower prices and improve the ability of everyone to get to their job easily and heat and light their homes within the limits of a their budgets. In their own ways Hanna and Johnson sought ways to find a way to move out of adolescence into a maturity that would allow the new industrial, urban, polyglot America to survive in concert with the founding ideals of the nation. During the next two decades the more Progressive ideals of Johnson would prevail both locally and nationally and would make Cleveland an example of good governance and progressive thought, an accolade that would receive more national attention that those once lavished on the splendors of Euclid Avenue.

Epilogue

At the end of the nineteenth century, Solon and Emily Severance were residents of Euclid Avenue. Their home, near what is now E. 88st Street was close to the one which their nephew, John L. Severance built in 1891. Solon’s brother, who had made his fortune with Standard Oil, initially planned to build alongside Solon and Emily, but changed his mind[xxx]. But by this time the Avenue was in decline. The expansion of the downtown business district was making the western end of the street less tenable for residence and more valuable (and taxable) for commercial development. In other places air pollution and the encroachment of less exclusive neighborhoods on the borders of the Avenue lessened its appeal. Many of the families who had made their fortunes during the Gilded Age, and their next generations moved to newer exclusive developments — Wade Park, Cleveland Heights, and Shaker Heights — during the early decades of the twentieth century. Others retreated to what had been lakeside summer homes in Bratenahl or country estates in and around the Chagrin River Valley. By the 1920s Euclid Avenue had lost its luster or, if you will, its gilding. The demise of the grand street after a heyday that lasted only an average human lifetime is perhaps the most potent symbol of the chimerical nature of Gilded Age America and Cleveland — it was transient and ephemeral.

But, it was also real. The social and economic dislocations created during the era were painful and often resulted in violence and unknown numbers of very personal tragedies. The era’s challenge to conceptions of the United States as a Jeffersonian agrarian Eden was upsetting. It opened wider an existing rift between city and countryside, one which still remains apparent in maps of contemporary red and blue America. It also created an industrial aristocracy antithetical to early conceptions of the United States as a classless democracy.

Yet, for Cleveland it functioned as an adolescence that evolved into one of the most enviable Progressive maturities in the United States. The seeds of Progressivism in Cleveland can be found in many aspects of its Gilded Age experience. There was no abrupt transition from one era to another. The local Progressive era had begun over a decade before the close of the century. The continued service of “good” men in the office (albeit absent of much power) of mayor was significant. That involvement served as a model for good government organizations such as the Municipal Association of 1895 which counted many leading citizens among its members.[xxxi] Equally significant was the ability of local leadership to transfer aspects of rational corporate and business management to politics and the handling of social problems. Tom Johnson ran his administration as a business. The creation of the Charity Organization Society in 1881, which became Associated Charities in 1900, was the first stage in a movement toward a rational, secular approach to poverty and need in the city.[xxxii] In a similar manner the business-friendly Chamber of Commerce championed building codes and other reforms that brought some order to a community that had often expanded in a helter-skelter fashion.

Whether the motivations for change in the waning years of the Gilded Age represented altruism or enlightened self-interest or, indeed, a form of co-option, will always remain debatable. What cannot be debated is that many who saw the strife and inequality of that era, or who smelled and breathed the pollution within the city were either appalled, or frightened, or both. Lincoln Steffen’s statement that Tom Johnson was the best mayor of the best governed city in the United States is often quoted as testimony to Cleveland’s importance in the Progressive Era. The fact that he made that statement only some twenty years after city treasurer Thomas Axworthy fled to Canada after misusing city funds is not only a testimony to Johnson, but to a city that understood it had problems to solve. Enlightened self-interest and good intent have to be recognized as unified factors that propelled Cleveland’s transition to a community noted for good government, rationally organized charities, and cultural sophistication during the first two decades of the 1900s. It was a change that was both evolutionary and revolutionary.

While written accounts of the past tend to seem abstract and distant, there is a place in Cleveland where one can view the tangible synthesis of the Gilded and Progressive eras. It happens to be located on Euclid Avenue. It is University Circle. Those who are determined to relive the splendor of Gilded Age Euclid Avenue can do so by visiting the museums, educational, and cultural institutions whose foundations rest on the fortunes that came from Gilded Age Cleveland and which house collections of art, costume and decorative arts that once were graced Euclid Avenue mansions. Annually, curators purchase new materials for display and scholarship by using funds from acquisition endowments created by families, such as the Wades and Hannas, who built their fortunes in Gilded Age Cleveland. But, visitors need also to recognize that that the institutions and collections also represent a progressive mentality, one which saw them as benefitting the common good of the community. A good number of the institutions were built in the circle after 1900, in the city’s post adolescence.

Here too, one can debate motivation for such altruism, whether it Gilded or Progressive. Does it represent, for instance, the imposition of particular cultural tastes, on the broader community? But the fact that the Cleveland Museum of Art, for example, is not named after an individual, like the Frick or the Freer galleries is significant as is the fact that in its first decades it also embraced the cultures and arts of the city’s immigrant communities.[xxxiii] The product of multiple bequests, it is a “Cleveland” museum. Similarly, the city’s world-renowned orchestra is the Cleveland Orchestra, and the institutes of art and music are “Cleveland” as well. Of course, the Cleveland Orchestra plays in Severance Hall, but that ensemble’s long history of educational work says much about its purpose — it was to educate and benefit the entire community. Certainly, Samuel Clemens, who dearly loved children and who easily sensed the deceptions and vanities of his age, might be delighted to know that he, as Mark Twain, could — had he miraculously lived into the 1930s — join an auditorium filled with schoolchildren at a concert in a hall built by John L. Severance, the nephew of his traveling companions, Emily and Solon.

[1]Diana Tittle, The Severances: An American Odyssey, from Puritan Massachusetts to Ohio’s Western Reserve, and Beyond (Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 2010), 126-135. The Clevelanders accompanying Twain on the trip were Emily and Solon Severance, Timothy and Eliza Crocker, Solomon Sanford, Timothy S. Beckwith, and Mrs. Abel Fairbanks. William Ganson Rose, Cleveland: The Making of a City (Cleveland: World Publishing, 1950) also ( 344) lists William. A. Otis as a member of the group.

[2] Population statistics noted in this paragraph and elsewhere are from Van Tassel and Grabowski, The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, web-edition, http://ech.case.edu, specifically from the timeline 9http://ech.cwru.edu/timeline.html) and the immigration statistics chart (http://ech.cwru.edu/Resource/text/FBPCACC.html).

[3] “Civil War” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=CW1 Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See Albert A. Nofi, A Civil War Treasury (Cambridge: DaCapo Press, 1992), 381-383, for military pay scales during the War.

[6] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 442-443 provides an excellent overview of the financing of the war. The possible impact of bond investments on Cleveland’s Gilded Age history is something that was explored by Dr. Edward J. Pershey when he was researching an exhibit on Cleveland in the Civil War for the Western Reserve Historical Society.

[7] “Civil War,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

[8] James Beaumont Whipple. “Cleveland in Conflict: A Study in Urban Adolescence, 1876-1900”. (Ph.D. diss, Western Reserve University, 1951).

[9]“Timeline,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

[10] Rose. 296 and 617.

[11] Rose, p. 376 and p. 617.

[12] Jan Cigliano, Showplace of America: Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue, 1850-1910, (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1991). This volume provides a solid social and economic history of Euclid Avenue and the families who resided there and serves to counter much of the local mythology that has come to encumber the history of the street.

[13] Grace Goulder Izant, John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years, (Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1973) provides an excellent overview of Rockefeller’s life in the city, including the period up to 1884 when he was a fulltime resident and the subsequent period after he had established residency in New York City, but continued to return (until 1915) to Cleveland annually. Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., (New York: Random House, 1998) adds nuance to the Izant volume and, importantly, outlines his business strategies and innovations.

[14] “Cleveland Rolling Mill Strikes” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=CRMS, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. See also Henry B. Leonard, “Ethnic Cleavage and Industrial Conflict in Late Nineteenth Century America: The Cleveland Rolling Mill Strikes of 1882 and 1885,” Labor History 20:4 (Fall, 1979), 524-48.

[15] Whipple, 85-89. “Labor” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=L1Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

[16] “Labor,” Streetcar Strike of 1899” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=L1, Encyclopedia Whipple, 177-189.

[17] Whipple, 111-120. Full on-line text of The Breadwinners is available at Project Gutenberg.

[18] Whipple, 163-174

[19] “Labor” “Socialist Labor Party” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=SLP, “Ruthenberg, Charles,” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=RC4, Encyclopedia.

[20] Thomas F. Campbell and Edward M. Miggins (eds), The Birth of Modern Cleveland, 1865-1930 (Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society/Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1988), 298-299. Additional biographical information on mayors during this period was taken from their biographies in the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

[21] Carol Poh Miller and Robert Wheeler, Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1990, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 95. See Whipple, 259, for the full statement by the mayor.

[22] “Streets” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=S23 and “Water System” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=WS, Encyclopedia.

[23] “Cleveland Public Schools” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=CPS2, Encyclopedia for the 1866 figure; Campbell and Miggins, 356 for the 1900 attendance.

[24] Whipple, 337, 339, 343.

[25] Ibid., 346.

[26]Campbell and Miggins, 300-305.

[27] Marcus A. Hanna, http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=HMA, Encyclopedia.

[28] Tom L. Johnson, (Elizabeth Hauser, ed), My Story, (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1993), 17.

[29] Ibid., li

[30] Tittle, 236-237, Cigliano, 174-175

[31] Campbell and Miggins, 303-305. See also “Citizens’ League of Greater Cleveland” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=CLOGC, Encyclopedia.

[31] “Associated Charities” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=AC7 and “Philanthropy” http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id=P6, Encyclopedia.

[32] Campbell and Miggins, 214-216.