Series from Plain Dealer about Steel Industry in Cleveland October, 2016

The Rise of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Belt)

The Rise of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Belt) 2015

Housing Crisis in Northeast Ohio – Where are We in 2015? Video from Forum October 7, 2015

Housing Crisis in Northeast Ohio – Where are We in 2015?

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 7-8:30 p.m.

CWRU Siegal Facility in Beachwood, OH

Panelists:

• Thomas Bier, Senior Fellow, Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University

• James Rokakis, Former Cuyahoga County Treasurer, Cleveland Councilman, Director Thriving Communities Institute

Moderator: Brent Larkin, The Plain Dealer

Northeast Ohio was one of the hardest hit housing markets in the U.S. in recent years. The market has begun to recover, but housing values and real estate taxes remain two of the most important economic issues facing local residents today. This forum will discuss current home prices, new construction, demolitions and foreclosures.

Cosponsored by City Club of Cleveland, Cleveland Jewish News Foundation, CWRU Siegal Lifelong Learning, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland

Here are two news stories from the forum

“Come to Cleveland? Maybe Not” Belt Sept, 2015

Come to Cleveland? Maybe Not” Belt Sept, 2015 by Daniel McGraw

‘Lady Artha’ Woods served on Cleveland council, managed boxers and more Plain Dealer 5.10.2010

Artha Woods, who died Monday, once burst into Mayor Dennis Kucinich’s office, got him to cancel a meeting and took him to see hookers hawking their wares in her ward.

She also traced some of the customers’ car registration tags and called their homes.

Woods longtime councilwoman and council clerk, died at McGregor at Overlook after a long illness. Different public records put her age at 94, 90, 88 and younger.

She broke the color line at Ohio Bell, managed boxers, ran a racially pioneering modeling school, mentored Jayne Kennedy and other stars and led local and national civic groups.

The slim, tall woman was known as “Lady Artha.”

“She was a great woman,” said her companion, Stanley Tolliver, former Cleveland school board member.

“She was a convergence of formality, professionalism and street smarts,” said long-time Councilman Jay Westbrook.

“She was always trying to advance black women,” said Councilman Ken Johnson.

Woods often denounced sexism and racism. In 1985, blasting police neglect of her East Side ward, she said, “This is getting to be a prime area, and I’m beginning to wonder if they don’t want black people living in the area.”

Yet she reached out to all races, especially after beating Councilman John Lawson for a new Ward 6, combining her old Fairfax ward with his University Circle one. She was named an honorary Italian at Holy Rosary Church and blessed by Pope Paul VI in Rome for her work with Catholic leaders.

She was born Artha Mae Bugg in Atlanta and had four younger siblings. The family moved to Cleveland before she started kindergarten. She became valedictorian of Central High School and won a district award as a top Latin student. She was raised as a Seventh-Day Adventist, without shows or dances. She later joined Antioch Baptist Church near her long-time home on E. 89th St.

Woods attended Western Reserve School of Education and took courses elsewhere in shorthand, modeling, sewing and more.

After public protests for diversity, Ohio Bell hired her and 18 other blacks in 1941. All the black women operated elevators at headquarters on Huron Rd. Black women had to sit at a separate table from white women in the cafeteria. She started boycotting the room.

She rose during 40 years at Ohio Bell and retired as public relations manager. Along the way, she led civic projects for the company, including “Reaction Line,” a program with Parent-Teacher Associations for city schools. Woods also managed two boxers and sewed rhinestone robes for them. She owned Cedar Ave. Millinery Shop and sold hats to Dorothy Fuldheim, Billie Holliday and Zelma George.

She had trouble finding black models. With partner Jon McCullough from Ohio Bell, she founded Artha-Jon Academy of Modeling and Charm at her E. 89th St. home, one of the nation’s first such schools for black women.

She ran the school for 30 years and passed it on to a granddaughter. She formed a foundation to teach the underprivileged for free. She also created a pioneering charm course for clients of the Cleveland Society for the Blind

She edited “International Image” for the Modeling Association of America International and became the group’s first black president in 1978. She and McCullough were inducted to the Models Hall of Fame.

Woods founded the Fairfax Area Community Congress, donated its building and created its Starlight Cotillion for female graduates of nearby public high schools.

“These young women deserve a moment in the spotlight,” she told The Plain Dealer in 1990.

Woods was also president of the Champs scholarship organization, the Booth-Talbert Clinic and Day Care Center Auxiliary and the Business and Professional Women’s Club. She belonged to the Cuyahoga County Democratic Executive Committee. She was second vice chairperson of the Metropolitan Health Planning Corp. and second vice president of the Urban League. She was a convenor of the National Black Caucus of Girl Scouts of America.

In 1977, she ran in Ward 18 against incumbent Councilman James Boyd, convicted of bribery inJuly. A few days before the election, he was jailed and removed from office. She was appointed to the seat, then won a full term at the polls.

On council, Woods helped the Cleveland Clinic and Cleveland Playhouse expand and pressed for minority contractors. To fight graffiti, she proposed registering buyers of spray paint. She also fought for improvements at the public Woodhill Homes.

“Very little is being done for you,” she once told Woodhill tenants. “Instead, they’re doing it to you.”

In 1981, she won the merged Ward 6. Nine years later, she stopped serving on council and started serving it as clerk. Westbrook, then a new council president, said, “She was an invaluable part of the team that moved us forward.” She oversaw renovations of council offices, put the city’s dormant consumer affairs department under council’s wing, and got the office’s first fax machine.

Among many hobbies, Woods liked to sew, swim, landscape, watch sports and raise German shepherds. She built a heated swimming pool and brick doghouse at her home. She won a landscaping commendation from Governor John Gilligan. Among many other honors, Artha Woods Street and Artha Woods Park are named for her.

Woods outlived her two children, one of them killed by gunfire at age 24.

She once said, “There was always rebellion in me, but I rebelled in a productive way, even in the face of blatant segregation.”

Artha Mae Woods

Survivors: two granddaugh ters, Gaile Ozanne of Pepper Pike and Deborah Enty of Cleveland; and six great-grandchildren.

Arrangements: E.F. Boyd & Son

Funeral: pending

Artha Woods:First Black Woman City Council Clerk Passes Away WEWS 5.13.2010

Artha Woods:First Black Woman City Council Clerk Passes Away

Newsnet5.com

Posted May 13th 2010

Artha Woods was the kind of woman who, when she entered a room, drew the positive attention of almost everyone who saw her. Those in government leadership positions in Cleveland City Hall speak of her using the terms “elegant” and “class.”

She was often affectionately called “Lady Artha” because of her bearing. Artha Woods was a longtime Cleveland City Councilwman. In 1977, she was appointed to the seat held by Councilman James Boyd, who, convicted of bribery, had to give up the seat. She then won a full term to the Ward 18 council seat. Years later, she was selected as the clerk of city council.

Artha Woods died Monday of natural causes. In recent years, she was a resident of a Cleveland nursing home.

Councilman Jay Westbrook remembers Woods as a woman who was “elegant,” but one also who was dedicated to the people.

“Artha was always quick sot stand up for her community; stand up for what she knew was right,” said Westbrook. “She was defintely her own person.”

During her years as clerk of council, Woods kept up with the many pieces of legislation passed by the councilmembers. She worked closely with then-council president Westbrook.

“She would let me know what she thought even if I did not agree with her,” said Westbrook as he spoke of the woman who worked by his side.

Councilman Jeff Johnson remembered Woods as one of two women on the council who helped guide him through his freshman year.

“One was the late Fannie Lewis and the other was Artha Woods,” said Johnson. He said Woods showed him the ropes of how legislation was passed in city council.

“She was tough,” he said with a smile on his face.

“She was the velvet glove over the iron fist; that’s how Artha was,” said Johnson. “But get her riled up and when she was fighting for a cause, that came out, too.”

She had many talents, which showed themselves even in the earliest years of her life. In 1941, after public protests for Ohio Bell to integrate its office, Woods and 18 other blacks were the first blacks hired by the telephone company. All the black women operated elevators at Ohio Bell’s headquarters on Huron Road in downtown Cleveland.

When she learned black women had to sit at a separate table from white women in the cafeteria, Woods began to boycott the room.

She persevered at the company during her 40 years with Ohio bell. She retired from the company as a public relations manager. She was also involved with a modeling school for young women. She even managed two boxers.

At Cleveland City Council’s committee room, Woods’ portrait hangs on the wall with those of two other council clerks. She has long been held in high esteem because of her ability to bring a relative quiet to political arguments on the council floor.

That was always quite a job because of the large numbers of councilmembers. When Woods joined the council, she was one of 33. Later, the council was pared down to a lesser number.

When Woods retired from the clerk of council job in the late 1990s. ther were tributes in her honor at city hall. When she died Monday, many at City Hall took notice.

“She made advancements for women, for African-Americans, for community residents and for City Hall,” said Westbrook. “She was a real voice for people.”

Johnson called her a “giant.”

The impression she left was the same one she brought — dedication to the people and dignity for herself. Her longtime friend, community activist and former Cleveland School Board member Stanley Tolliver, called woods “a remarkable woman.”

Her funeral will be held Friday at 11 a.m. at Liberty Hill Baptist Church, 8206 Euclid Ave., in Cleveland. It will follow a 10 a.m. wake for the woman many in City Hall called “Lady Artha.”

Records put her age at 99, 90, or 88. Tolliver said she was 90. Whatever was her age, Woods left a strong and positive impression at Cleveland City Hall and throughout the Northeast Ohio community.

“The President From Canton” by Grant Segall

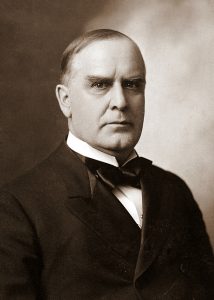

William McKinley

THE PRESIDENT FROM CANTON

by Grant Segall

Greeting the nation from his front porch in Canton, nursing his frail wife, sporting scarlet carnations from a foe, soft-peddling his views, the dapper little William McKinley seemed like the quintessential Victorian. The impression deepened when assassin Leon Czolgosz from Cleveland froze him in time and Teddy Roosevelt rough-rode into the Progressive era.

But McKinley launched what became known as the American Century. He helped make a former colony a colonizer and the world’s biggest manufacturer. He planned the Panama Canal and the Open Door policy toward China. He promoted labor rights, mediation and arbitration. He created the White House’s war room, press briefings and press receptions.

He also started a century-long rise in presidential power. Future President Woodrow Wilson wrote in 1900, “The president of the United States is now, as of course, at the front of affairs, as no president, except Lincoln, has been since the first quarter of the 19th century.”

McKinley broadened a Republican base that mostly dominated until 1932. While he quaintly campaigned from his porch, innovative backers paid the way of an estimated 750,000 visitors from around the country. They also used early polls and movies.

Historian Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University once told The Plain Dealer, “McKinley was the first modern president.”

Biographer Kevin Phillips wrote, “The Progressive era is said to begin with Teddy Roosevelt, when in fact McKinley put in place the political organization, the antimachine spirit, the critical party realignment, the cadre of skilled GOP statesmen…, the firm commitment to popular and economic democracy and the leadership needed.”

Supporters called him the Idol of Ohio. Critics called him Wobbly Willie. Republican boss Tom Platt of New York thought the Ohioan “much too amiable and much too impressionable.” Joseph Cannon, future House speaker, said McKinley kept his ear so close to the ground, grasshoppers jumped inside.

McKinley was hard to gauge. He wrote little, spoke calmly and wore mild expressions. But colleagues saw a master behind the mask. Fellow Congressman Robert LaFollette, future Wisconsin governor and senator, said, “Back of his courteous and affable manner was a firmness that never yielded conviction, and while scarcely seeming to force issues, he usually achieved exactly what he sought.” Elihu Root, McKinley’s war secretary, later Nobelist and senator, said the president would “bring about an agreement exactly along the lines of his own original ideas while [Cabinet] members thought the ideas were theirs.”

Most modern historians agree. Quentin R. Skrabec wrote, “It might be argued that McKinley’s behind the scenes approach was more effective than Roosevelt’s headlines.”

McKinley avoided serious scandals. He refused speaking fees and corporate jobs while in Congress. He shunned endorsements that required patronage.

Some editorial cartoonists drew him as a puppet of Cleveland ally Marcus Alonzo Hanna, dubbed “Marcus Aurelius” or “Dollar Mark.” In 1893, when the economy tumbled, Hanna and fellow tycoons paid off a $130,000 debt that McKinley had incurred backing a friend’s business. Critics sneered, but most of the public sympathized.

While chief executive, McKinley said, “I have never been in doubt since I was old enough to think intelligently that I would someday be made president.”

McKinley was the sixth elected Republican president in a row born a Buckeye. He was born Jan. 29, 1843, the seventh of eight children in a Scotch-Irish, Whig, abolitionist family. He was raised in the northeastern Ohio towns of Niles, Poland and Canton. His father, William Sr., managed and co-owned an iron foundry. Historians say McKinley grew up to promote the local kind of capitalism: small, independent, businesses with good products, good wages and good returns.

He went to a Methodist academy and was baptized. He entered Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., but soon came home ill and grew depressed. He clerked for the postal service and taught school.

When the Civil War broke out, McKinley enlisted. At Antietam, he insisted on delivering food and coffee through cannon fire. He rose to brevet major and served closely with future leaders like Rutherford B. Hayes. He would become the last of several Civil War veterans in the White House, where he’d go by “Major,” not “Mr. President.”

In peacetime, McKinley spent a year at Albany Law School and started a practice in Canton. Soon he became a Mason, local YMCA president and Stark County Republican county chairman. He was elected county prosecutor in 1869 and narrowly defeated in 1871.

He fell in love with a rare female bank cashier: the slim, blue-eyed, curly-haired Ida Saxton, whose leading family owned the bank and the Repository, a Republican-minded newspaper. The couple married in 1871, when she was 23 and he nearly 28, old for newlyweds back then. They rented two modest houses in turn from her family before finally buying one in 1900. The other is now called the Saxton-McKinley House, part of the National First Ladies Historic Site.

The couple’s two girls died young. The grieving mother developed seizures and became an invalid for the rest of her life. William took to reading the Bible and playing cars with her for a couple hours per day.

In 1876, miners were arrested for rioting in nearby Massillon. McKinley defended them for free. Just one was convicted. The lawyer’s success turned a foe, mine owner Hanna, into a supporter.

That year, at age 34, McKinley won election to Congress. Over the next 14 years, Democrats tried to gerrymander him out of office whenever they could. He lost in 1882 but retook the seat in 1884. One opponent always gave him a carnation to wear for their debates. McKinley wore the seemingly lucky flower for life.

The congressman championed tariffs to boost domestic goods and wages. He backed the Interstate Commerce Act and the Sherman Antitrust Act. On one of the era’s hottest issues, he supported “sound money” standards of gold and sometimes silver too.

In 1888, he was wooed for the presidential nomination but kept a pledge to support Ohio Senator John Sherman. In 1890, he narrowly lost a bid for speaker of the House but began to chair the powerful Ways and Means Committee.

That year, he passed the McKinley Tariff, raising rates on most imports to a record 48 percent, but conceding some breaks for special interests. The Democrats gerrymandered his seat again, and phony peddlers offered goods at daunting prices blamed on tariffs. He lost by 300 votes, but won the governorship in 1891 and again in 1893.

He persuaded the Statehouse to tax railroads, telegraphs, telephone lines and foreign corporations. He won a labor arbitration board and fines for bosses who fired unionists. He promoted workplace safety, led a relief drive for starving miners and successfully mediated a railroad strike. He also sent the National Guard to quell a violent strike.

McKinley reportedly waved to Ida every morning from the spot outside the Statehouse where his statue now stands, then waved again every afternoon from a window. She tried to attend official events but often had fits during them. He calmly covered her face with a handkerchief or carried her from the room.

In 1892, he refused presidential consideration again but finished third at the convention anyway. In 1894, he stumped in 300 cities for Republicans. The next year, he declined renomination as governor and took quiet aim at the White House.

By tradition, he stayed home during the 1896 convention. He won on the first ballot, with 661 1⁄2 votes to 84 1⁄2 for his nearest rival. The vice-presidential nominee was Garret Hobart, head of the New Jersey state senate.

As Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland prepared to step down, William Jennings Bryan swept the Democratic and Populist nominations with his “cross of gold” demand for free and unlimited currency. Then he stumped over 18,000 miles and seemed to surge.

McKinley kept to his porch meanwhile. “I might just as well put a trapeze on my front lawn… as go out speaking against Bryan,” he reportedly said. “I have to think when I speak.”

But his homey campaign was hardly homespun. Like James Garfield in Mentor 16 years earlier, he gave well-scripted greetings that newspapers spread afar. He campaigned for a “full dinner pail.” He said, “It is a good deal better to open up the mills of the United States to the labor of America than to open up the mints of the United States to the silver of the world.”

Hanna billed him as an “advance agent of prosperity.” The tycoon deployed some 1,400 speakers and 200 million pamphlets in a nation of just 14 million voters. He raised a war chest estimated anywhere from $3.5 million to $10 million, which would be worth about $269 million in 2014 dollars. The bounty included $250,000 from John D. Rockefeller, Hanna’s schoolmate at Cleveland’s Central High School.

Bryan’s polemics—rural, nativist, fundamentalist and classist—eventually turned many previously Democratic workers in the swelling cities toward moderate, inclusive McKinley. The Republican got 271 electoral votes to 176 and 51.0% of the popular votes—the first presidential majority in 24 years.

Taking office on March 4, McKinley called a special session of Congress and won the highest tariffs yet. Soon the economy began to surge. In 1898, for the first time, the U.S. would export more manufactured goods than it imported.

Meanwhile, McKinley stripped civil service protections from about 4,000 jobs. His first cabinet picks were weak, and six of the eight fell out during the first term. But his choice of an aging John Sherman for secretary of state opened up a Senate seat for Hanna.

The president appointed some black officials and pushed recruitment and promotion of black troops, but did little else to stop the nation’s rising discrimination. He visited the Tuskegee Institute and Confederate memorials. He denounced lynching but did little to stop it.

McKinley telegraphed, telephoned and traveled widely. He became the first president to visit California. Death stopped his plans to be the first abroad, but he’d already crossed borders in other ways. He helped pass the Hague Convention on warfare and create the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration. He helped crush China’s Boxer Rebellion and launch the Open Door policy to help U.S. exports there. He sent Marines to Nicaragua to defend Americans’ property.

In 1898, journalists and “imperialists”—a positive word at first—urged McKinley to free Cuba from a brutal Spain. McKinley balked. “I have been through one war; I have seen the dead piled up; and I do not want to see another.”

Then the Maine sank off Havana, and Navy officials blamed a probably innocent Spain. McKinley led what Secretary of State John Hay of Cleveland famously called “a splendid little war.” The president directed the troops in some detail. He won wartime taxes on high inheritances and more. He also persuaded Congress to annex Hawaii.

The war took just four months. Spain agreed to free Cuba and cede Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the U.S. The Senate narrowly accepted the territories, and U.S. troops spent four years quelling Filipino insurgents.

Unlike most predecessors, McKinley stumped for congressional candidates in mid-term. The Republicans kept control of both houses.

He sought treaties on dual standards for currency, but gold strikes were undercutting silver. In 1900, he signed the Gold Standard Actwith a gold pen.

At the 1900 Republican convention, the only question was who’d replace the late Hobart as vice president. Hanna lobbied hard against Roosevelt, but McKinley refused to interfere, and the New Yorker prevailed.

Bryan was renominated by the Democrats and stumped widely again, as did Roosevelt. McKinley returned to his porch, and Hanna raised more millions. The incumbent’s victory was bigger than before: 292 to 155 in electoral votes; 51.7 percent to 45.5 percent in popular votes.

During his second term, he planned a commerce and labor department. He also told an aide, “The trust question has got to be taken up in earnest, and soon.” He’d already called trusts “dangerous conspiracies… obnoxious to common law and the public welfare.” But his attorneys said they lacked power against the trusts, and he proposed no stronger laws.

On Sept. 5, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, he said treaties to lower tariffs would help the nation’s growing industries. “We should sell anywhere we can and buy wherever the buying will enlarge our sales.”

Despite rising assassinations overseas, he insisted on shaking hands with strangers at the exposition the next day. “No one would wish to hurt me,” he said. A young girl reportedly asked for his lucky carnation. He complied. Then Czolgosz approached to act for anarchy. McKinley offered a hand. A bullet flew deflected off his coat button. Another lodged in his stomach.

The crowd grabbed Czolgosz. “Don’t let them hurt him,” McKinley murmured from a chair. He turned to his secretary, George Cortelyou: “My wife, Cortelyou, be careful how you tell her – oh, be careful!”

McKinley languished for eight days at a nearby house. Doctors spoke optimistically but missed the bullet and a case of gangrene. On the 13th, he said, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Ida cried and begged to go with him “We are all going; we are all going,” he replied. “God’s will be done, not ours.” He died early the next day.

Roosevelt took the oath and said, “It shall be my aim to continue absolutely unbroken the policy of President McKinley.” Czolgosz was promptly tried and electrocuted.

McKinley grew even more popular in death. Mourners put his likeness on the $500 bill, his name on the continent’s highest mountain and his coffin in a new memorial in Canton. They also made Ohio’s state flower the scarlet carnation.

McKinley’s reputation has weathered well. Biographer Kevin Phillips called him “an upright and effective president of the solid second rank.” H. Wayne Morgan wrote, “He was not a ‘great’ president, but he fulfilled an exacting and critical role with success and ability displayed by no other contemporary.”

For further reading:

William McKinley by Kevin Phillips, 2003, Henry Holt & Co.

The Presidency of William McKinley by Lewis L. Gould, 1980, University Press of Kansas.

William McKinley and His America by H. Wayne Morgan, 2003, Kent State University Press.

William McKinley and Our America by Richard L. McElroy, 1996, Stark County Historical Society.

Places to visit:

McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, 800 McKinley Monument Dr. NW, Canton, OH 44708, 330-455-7043, www.mckinleymuseum.org.

National First Ladies’ Library, 331 Market Ave. S., Canton, OH 44702, 330-452-0876, www.firstladies.org.

About the Author

Grant Segall has spent 39 years on daily newspapers, including 30 at The Plain Dealer. He currently writes the My Cleveland column and covers the Berea school district for the PD and Sun News. He has shared in three national prizes and won several state and regional ones.

Segall has freelanced for Time, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil has been published by Oxford University Press and by houses in Korea and China. His short stories have been published in college journals, including Whiskey Island at Cleveland State, and in independent zines. He lives in Shaker Heights and has three sons.

Arnold Pinkney was one of Cleveland’s most effective political strategists: Brent Larkin

Arnold Pinkney was one of Cleveland’s most effective political strategists: Brent Larkin

Stay connected to cleveland.com

Arnold Pinkney was blessed with the rare ability to figure out where voters were headed, and get there first.

That gift made Pinkney one of the most effective political strategists and campaign managers in Cleveland history.

Over the course of a political life that spanned nearly half a century, Pinkney’s candidates won a whole lot more races than they lost.

But Pinkney, who died Monday at the age of 83, didn’t win them all. And two of those losses were tough to take.

Because they were his own.

Pinkney ran for mayor in 1971 and 1975, defeated both times by Ralph Perk. Of the two, 1971 was, by far, the most disappointing.

In one of the most memorable mayoral races ever waged in Cleveland, events beyond Pinkney’s control conspired to cost him a victory.

Pinkney’s mentor was former Mayor Carl Stokes. He worked as a top City Hall aide to the nation’s first black, big-city mayor, and in 1969 managed Stokes’ winning re-election campaign.

Of all the members of the city’s growing black political class in the 1960s, Pinkney always thought Stokes stood head and shoulders above them all.

“Only one person had the charisma, the experience and the drive to win that job,” Pinkney recalled a few years ago. “Back then, it took a special talent for a black to be elected mayor. And only Carl had that talent.”

With the black church as its foundation, Stokes’ political base was built to last. And when he decided not to seek re-election in 1971, Pinkney hoped to use that base to become the city’s second black mayor.

Stokes quickly got on board. But first he had a score to settle.

Partisan primaries were held in those days. In the Republican primary, Ralph Perk easily dispatched a young state representative from Collinwood named George Voinovich.

Pinkney ran as an independent, leaving Council President Anthony Garofoli and businessman James Carney as the Democratic candidates.

Stokes disliked Garofoli, and in the waning days of the primary campaign he recorded a message endorsing Carney that was telephoned into the home of virtually every black voter in the city. Political robo-calling was in its infancy at the time, but that call enabled Carney to upset the favored Garofoli.

Stokes had flexed his sizable political muscle to punish a fellow Democrat, but he was playing a risky game. After convincing blacks to support Carney in the primary, he asked them to switch back to Pinkney in the general election five weeks later.

It backfired. About one in five black voters stuck with Carney, enough to swing the election to Perk, a Republican.

The 1971 campaign was my first as a reporter for the Cleveland Press. And I distinctly remember that, aside from Perk and a handful of his closest allies, no one thought he would win.

Afterwards, some who knew Stokes well thought he never wanted Pinkney to win, that he wanted at the time to be known as Cleveland’s first — and only — black mayor.

Pinkney never bought that. But he did come to believe Stokes’ strategy cost him the election.

“There’s no question Stokes’ endorsement of Carney siphoned votes from me 35 days later,” he recalled 20 years later. “I indicated to him (Stokes) that I didn’t think the strategy would work, but Carl prevailed.”

By 1975, Cleveland had switched to nonpartisan mayoral contests where the top two finishers in the primary would meet in a runoff election.

In the primary election, Pinkney finished first in a five-candidate field, nearly 4,000 votes ahead of Perk, who was seeking a third, two-year term.

Years later, Perk would admit he played possum in the primary. By taking a dive in Round 1 of the voting, Perk hoped to scare his supporters (i.e. white voters) and increase turnout on the West Side.

It worked. In the runoff election, he beat Pinkney by 17,000 votes.

Pinkney never again sought elected office, instead devoting his time to campaign consulting and selling insurance.

He played a key role in many statewide campaigns, notably Dick Celeste’s three runs (two of them successful) for governor. In 1984, he managed Jesse Jackson’s race for president.

When Gerald Austin, another veteran political consultant with deep Cleveland ties, was offered the job of managing Jackson’s presidential campaign in 1988, the first person he called was Pinkney.

“Arnold told me if Jackson and I could both control our egos, we’d learn a lot from each other,” recalled Austin. “So I took it. Arnold was special. He was a wonderful teacher, a real gentleman, a dear friend.”

For 40 years, Pinkney, Lou Stokes and George Forbes formed a political triumvirate that permeated every aspect of black political life in Greater Cleveland.

One Saturday morning in the late summer of 2011, Pinkney and House Speaker Bill Batchelder sat at a table in Forbes’ home and drew a new congressional district that protected the seat held by Rep. Marcia Fudge. Stokes signed off on the district via telephone.

Slowed a bit by illness, Pinkney nevertheless played an instrumental role in the 2012 school levy campaign that saw voters overwhelmingly agree to fund Mayor Frank Jackson’s school reform plan. And last fall he served as an adviser to Jackson’s re-election effort.

Former Plain Dealer editorial page editor Mary Anne Sharkey worked with Pinkney on those and other campaigns. From Pinkney, she learned the importance of a ground game in winning citywide elections, watching as he “dispatched troops with the precision of a general.”

Pinkney wasn’t averse to using social media and other 21st-century political tools, but his talents and tactics remained decidedly old school. Nevertheless, they worked.

“Arnold had a golden gut,” said Sharkey. “He did not need focus groups. He knew this town.”

About as well as anyone who ever lived.

Brent Larkin was The Plain Dealer’s editorial director from 1991 until his retirement in 2009.

Arnold Pinkney obituary from Plain Dealer

Arnold Pinkney obituary from Plain Dealer January 13, 2014

http://www.cleveland.com/open/index.ssf/2014/01/post_51.htmlPolitical strategist Arnold Pinkney, consultant to Jesse Jackson, Frank Jackson and others, dies

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Arnold Pinkney, who rose from the steel mills of Youngstown to become a nationally known political strategist and the manager of Jesse Jackson’s historic presidential campaign, died Monday — mere months after his most recent campaign.

He was 83.

Pinkney was best known locally as the shrewd kingmaker who put Louis Stokes in Congress and Frank Jackson in the Cleveland mayor’s office. In between, he was a trusted tactician for former Mayor Michael R. White and former Ohio Gov. Richard Celeste.

Friends said Pinkney had been ill for months. But his influence remained considerable in local politics. Last June he endorsed Armond Budish for Cuyahoga County executive, becoming one of the Beachwood-based state representative’s key early backers. He also remained close with Mayor Jackson through his successful bid last fall for a third term.

A statement from Hospice of the Western Reserve and forwarded by the Cleveland NAACP said Pinkney passed at 1:30 p.m. at the David Simpson Hospice House. His family thanked well-wishers but asked for privacy in the statement. Arrangements with the E.F. Boyd & Son Funeral Home are pending.

“The Cleveland community has lost a remarkable public servant who cared deeply about the future of our children and the well-being of all people,” said U.S. Rep. Marcia Fudge, a Democrat from Warrensville Heights and chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus. “Mr. Pinkney has been a friend and an astute political mentor to many, including me. My thoughts and prayers go out to his wife Betty, his daughter Traci and all other members of his family.”Said Budish, in an emailed statement: “Our hearts, thoughts and prayers go out to Arnold’s family today. Mr. Pinkney was a dedicated leader and public servant not just to the African American community, but also to all of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. His imprint on this region has been historic, and he will be sorely missed but not forgotten.”

Political consultant Mary Anne Sharkey, who worked with Pinkney on levy campaigns and on Frank Jackson’s campaigns, said Pinkney remained engaged on the mayor’s recent re-election campaign. She recalled working with Pinkney to prepare Jackson for a City Club of Cleveland debate with challenger Ken Lanci.

“Arnold paid attention to everything from soup to nuts,” said Sharkey, who was at Cleveland City Council’s Finance Committee meeting Monday afternoon as word of Pinkney’s death spread. Council members, she said, observed a moment of silence.

An insurance broker, Pinkney drew national attention as the campaign manager in civil-rights leader Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential bid. Jackson didn’t win, but he credited Pinkney with running a campaign that mobilized millions of previously disenfranchised poor and minority voters.

“I am very sad today,” Jackson told the Northeast Ohio Media Group in a telephone interview Monday. “With his passing, a huge part of history goes with him — that generation, led by Carl Stokes and Lou Stokes.

“A civic leader who could push or pull,” Jackson added. “He could manage in the background or lead from the forefront. He was forever blessed with a good mind and courage and could be trusted. His legacy of service will be with us a long time.”

Pinkney often said the highlight of his career occurred years earlier in the ballroom of the Beverly Hills Hilton in Los Angeles.

Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humphrey had made a strong showing, but narrowly lost the California primary in his quest for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. As the partisan crowd cheered, the former vice president’s wife, Muriel, motioned for Pinkney — then her husband’s deputy campaign manager — to join the candidate on stage.

“We’re going to win this race,” Humphrey told Pinkney on national television. “And if we win, you’re coming to Washington with me to help put this country back together.”

Everyone back in Ohio was watching, and Pinkney was convinced he was headed to the nation’s capital for a cabinet post or a high-level White House position.

“It was one of the proudest moments of my life,” Pinkney would recall years later.

Humphrey didn’t win, and Pinkney didn’t go to Washington. But his fascination with politics lasted until his death. It was an attraction that began at an early age.

An education in politics

His father, David, was vice chairman of the Mahoning County Republican Party and favored Wendell Willkie over Franklin D. Roosevelt. His mother, Catherine, served as a precinct committeewoman. Their politics cast the boy as an underdog in the overwhelmingly Democratic steel town.

“Me and one other kid, a white kid, were the only ones in our whole school to wear Willkie buttons,” he said with a chuckle.

Pinkney’s father died just three months before his son, the youngest of five children, graduated from high school. To help the family make ends meet, the 17-year-old Pinkney moonlighted in steel mills.

It was around that time that he discovered Humphrey, who was to become a surrogate father. Listening to the 1948 Democratic National Convention on the radio, the teenager heard the youthful mayor of Minneapolis deliver an impassioned plea for his party to embrace civil rights — a plea so strident it drove Southern segregationists from the Philadelphia convention hall.

The speech rang in Pinkney’s ears for years. Decades later in hotel rooms from Portland to Pittsburgh, Humphrey and Pinkney would share meals and talk politics until dawn. Pinkney rode in Muriel Humphrey’s limousine during the senator’s funeral.

Young Pinkney was moved by Humphrey, but his first ambition was to play baseball. His exploits on the diamond at Albion College in Michigan eventually landed him in the school’s sports hall of fame. A talented shortstop with a strong bat, Pinkney played ball with Major Leaguers while stationed in Europe during an 18-month stint in the Army.

Pinkney held his own with the big-leaguers, but Indians scout Paul O’Dea warned the young man that he would be in his late 20s by the time he made it to the majors.

“He said, ‘Your race needs more lawyers than baseball players,'” Pinkney recalled.

Heeding O’Dea’s advice, Pinkney came to Cleveland in 1955 and enrolled in law school at Western Reserve University, but dropped out when he ran out of money. He met his wife, Betty, while at Albion. The couple later had a daughter, Traci.

The young family man went to work, becoming the first black agent hired by Prudential Insurance Co. He was soon drawn to causes, heading a membership drive for the NAACP and picketing a supermarket chain for not hiring blacks.

Partnering with the Stokes brothers

Pinkney met the Stokes brothers while doing bail bond work, and he soon became involved in local politics. After seeing Pinkney run successful local judicial campaigns, Louis Stokes tapped Pinkney to run his 1968 Congressional bid. The victory made Stokes Ohio’s first black congressman. Pinkney’s reputation grew after he helped Carl Stokes, the first black mayor of a major American city, survive a tough re-election fight.

“It’s like watching a symphony,” Louis Stokes said of Pinkney’s campaigns during a 2001 interview. “I’ve seen a lot of campaigns and Arnold is unquestionably the best I’ve ever seen.”

Pinkney did not spend his whole career behind the scenes. He served as Cleveland school board president from 1971 to 1978. The post thrust him into the public spotlight during the start of the district’s tumultuous desegregation case.

Pinkney’s visibility grew, but it wasn’t enough to propel him to higher office. He made unsuccessful runs for mayor in 1972 and 1975. After the latter loss, he moved to Shaker Heights to remove himself from consideration for future races.

The affable Pinkney was known for campaigning hard in white West Side wards where support for a black candidate ranged for disinterest to outright hostility. Pinkney would later tell of walking into a Kamms’ Corner tavern and hearing himself being loudly disparaged by a guy standing at the bar.

“The guy said, ‘He don’t have the nerve to come in here,'” Pinkney recalled years later. “I tapped him on the shoulder and shook his hand. He said he lived in Fairview Park, but if he lived in Cleveland, he would have voted for me.”

But Pinkney also discovered a considerable down side to public service. While serving on the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority in 1984, Pinkney was convicted of having an unlawful interest in a public contract. Pinkney argued he sold insurance to the board only after a board attorney told him such a deal was legal.

Five years later, a state parole board unanimously recommended a full pardon, and Celeste, who was then governor, pardoned his old friend.

The reigning guru of Cleveland politics

Pinkney spent much of the last two decades championing candidates and causes he believed in. His knack of knowing exactly how many votes a candidate or issue needed to prevail — and precisely where to find those votes — established him as the reigning guru of Cleveland politics.

“Most people take political science course and that kind of thing,” said former Cuyahoga County Deputy Elections Director Lynnie Powell, who first met Pinkney as a 16-year-old campaign volunteer. “Arnold never really did that. He knew in his gut how to run a campaign and how to reach people.”

White, who met Pinkney when he was 14, frequently tapped into that expertise during his three terms as mayor. In a six-year period, White asked Pinkney to run campaigns on five issues, all of them successful: the 1995 effort to extend the countywide tax on cigarettes and alcohol to help pay for construction of Cleveland Browns Stadium; the 1996 Cleveland schools levy campaign; a 1997 campaign to defeat a charter change that would have limited the city’s ability to grant tax abatements; and a 2001 school bond issue.

“I’d rather be on his side than against him,” said Richard DeColibus, the retired Cleveland Teachers Union president who pushed the unsuccessful tax-abatement issue.

Pinkney ran lawyer Raymond Pierce’s mayoral bid in 2001, losing to Jane Campbell and rival political strategist Gerald Austin. But he got revenge four years later when he helped Frank Jackson defeat the Campbell-Austin team.

Through it all, Pinkney remained an active partner in Pinkney Perry Insurance, a firm he and Charles B. Perry opened more than 45 year ago. He also served on the boards of Albion and of Central State University in Wilberforce.

“I have a gift for getting people involved,” Pinkney said in a 2001 interview. “And I like doing it.”

This obituary was written by former Plain Dealer reporter Scott Stephens, with contributions from Plain Dealer reporter Grant Segall.

Remembering Arnold Pinkney Ideastream 2014

Remembering Arnold Pinkney

2014 Ideastream program after the passing of Arnold Pinkney