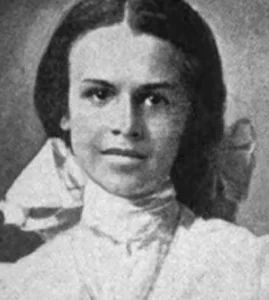

If you haven’t heard about the Black girl who won the first national spelling bee in the U.S. 115 years ago, you’re not alone: even many in her family didn’t know about Marie C. Bolden’s feat until after she died, decades later.

“It’s astounding to me” that she never talked about winning a gold medal in front of thousands of people, Bolden’s grandson, Mark Brown, told NPR.

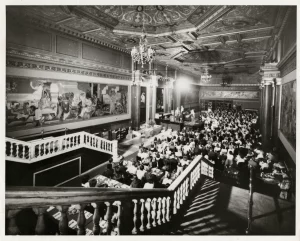

But back in 1908, Bolden’s victory made national news and upended racist stereotypes, less than 50 years after the Civil War. The 14-year-old did it by being perfect, spelling 500 words flawlessly to lead her hometown team, Cleveland, Ohio, to victory in the city’s then-new Hippodrome Theater.

“She never talked about this award, this amazing accomplishment,” Brown said. “But even Booker T. Washington mentioned [it] in his speeches.”

Bolden’s win was a national sensation

Boleden’s win was dramatic and unprecedented: Cleveland’s team was trailing in a field that included teams from New Orleans, Pittsburgh and Erie, Pa., near the end of the contest, according to contemporary accounts. But then Bolden vaulted her team to the top prize.

She never showed off the gold medal she won — in fact, her family isn’t sure what became of it — but in interviews after her win, Bolden told reporters she had studied hard for the competition, saying she wanted to help her city win, and that her mother and father wanted her to win.

“When I felt nervous at the Hippodrome, it steadied me to think of these things,” she was quoted telling The Plain Dealer. “I just kind of gritted my teeth and made up my mind that I wouldn’t miss a word.”

It was only after Bolden died that her family realized her place in history. Going through a box of her belongings, Brown says, they found a newspaper clipping from The Plain Dealer relating the story of the Black mail carrier’s daughter who out-spelled hundreds of white kids.

After her stunning victory, Bolden was hailed by “a storm of applause” and congratulations from hundreds of people, including members of the team from New Orleans, according to Indiana’s South Bend Tribune.

Bolden’s story has only emerged in recent years

Cleveland hosted the spelling contest in June 1908, using it as a marquee event to kick off the National Education Association’s conference. The contest is recognized as the first nationwide spelling bee by Guinness World Records — which also notes Bolden’s role.

The famous Scripps National Spelling Bee, which began in 1925, held its finals this week. Bolden’s accomplishment drew renewed attention in 2021, when Zaila Avant-garde became the first African American to win the Scripps contest.

Bolden’s story then drew the interest of Babbel, the language-learning software company, which contacted Brown after researching his grandmother’s win.

“Her parents and friends helped her memorize words, and she read a newspaper each day to perfect her spelling,” said Malcolm Massey, a language expert at Babbel. “It’s a blueprint for today’s would-be Spelling Bee champions.”