Newton D. Baker from Foreign Affairs April 1938

if above link does not work, try this

Terrific essay written about Newton D. Baker after his death by Frederick P. Keppel for Foreign Affairs Magazine, April 1938. Strongly recommended.

Newton D. Baker

By Frederick P. Keppel FROM OUR APRIL 1938 ISSUE

NEWTON BAKER, though a seasoned public servant, was far from being what is called a national figure when he went to Washington as Secretary of War in March 1916; and on the Atlantic seaboard at least, the appointment definitely offended our folkways. Of course the new Secretary had to be a Democrat, but here was clearly the wrong kind of Democrat. He came from Cleveland, not a good sign in itself, where he had been the disciple and successor of Tom Johnson; he had found nothing better to tell the Washington reporters at his first interview than that he was fond of flowers; and he belonged to peace societies (so did his predecessor, Elihu Root, but that was different). Could Woodrow Wilson have done worse had he tried?

Few of us changed our minds about Baker within the first months of his service. Yet at the Armistice he stood without question in the front rank of our citizens; and in direct violation of the rule that in an ungrateful democracy service in a national emergency is to be quickly forgotten, the years remaining to him were ones of steadily growing reputation. His death on Christmas Day last drew forth unique expressions of admiration and affection from all sections, all parties, and all classes. And yet the man who had died was the same man who came to Washington in 1916, ripened by time and by great responsibilities it is true, but the same man. The change was in ourselves. My effort here is an attempt to trace the steps and to set forth the reasons for that change.

The story of his administration of the War Department has been told by Frederick Palmer in “Newton D. Baker: America at War,” and told with sympathy and understanding; we cannot reach our objective by briefly repeating that story, nor can we reach it by comparing Baker’s record with that of his predecessors in wartime, and for two reasons: first, the vastness of the undertaking in 1917-18 threw all previous experience out of scale; and second, our military organization had, since the Spanish War, been re-created “under Elihu Root’s counselling intelligence” — to use Baker’s own phrase. What I set out to do is much more personal in character, and the task has not proved to be an easy one. Natural gifts and long practice had indeed made Baker one of our outstanding public speakers, and a volume of wartime addresses collected by his friends in 1918, “Frontiers of Freedom,” [i]provides fruitful reading, as do the addresses which later found their way into print, including his greatest effort — the eloquent and deeply moving plea for the recognition of the League of Nations made at the Democratic Convention of 1924. It is true, also, that no adequate collection of American state papers could fail to include a few of his departmental writings (in general, these are to be found in Palmer’s book) and that there are other important writings of his — to which reference will be made later on. The entire printed record, however, tells us but little about the man himself, for the good reason that when he spoke in public or wrote for publication the very last thing in his thoughts was Newton Baker. With his genius for friendship, he was, as Raymond Fosdick has pointed out, one of the few remaining exponents of an almost lost art, that of letter writing, and it would have been much more to our present purpose if his voluminous and many-sided correspondence had been available.

It has really been by something like a process of elimination that I have been brought to seek the nature and degree of Baker’s influence and the steady growth of his renown, not in the printed record, but rather by gathering together the impressions he made upon all sorts and conditions of men in direct personal contact. Inevitably my thoughts went back to the early days of the war, when I saw him daily and nightly, and what has come to me after these twenty years is no steady stream of recollection, but rather a cavalcade of separate incidents, of figures singly or in groups crossing the stage of memory — each individual as he left the scene carrying away some impression of the man.

Let me try to reconstruct a typical day in his office in the late spring or summer of 1917. At 8.30 A.M. Herbert Putnam might arrive, and in five minutes the Secretary would understand both the wisdom and the practicability of libraries in the training camps of our citizen army, and of having the books later accompany the soldiers to France. Next, a Plattsburg enthusiast who had come to scold might find himself, much to his astonishment, remaining to listen and learn; or some fellow liberal would have to be disabused of the idea that the war was a heaven-sent experimental laboratory for some pet social theory. Fosdick would drop in to go over some point about camp facilities, or Tardieu about the available ports of debarkation in France, or General Bridges about temporary provision for our soldiers in England. Big business and transportation and labor would have their representatives, and members of Congress were always in the anteroom, insistent on prerogative in direct proportion, it seemed to us, to the unimportance or impropriety of their purpose. At noon Baker would come out to give at least a handshake and a smile, often an understanding word, to the scores of private visitors for whom it was physically impossible to arrange private appointments. Then home to luncheon with his wife and children, his one act of self-indulgence. Afterward, there might be a quiet hour with Dr. Welch of Johns Hopkins on what modern medical care might contribute to the health of the soldiers. On such occasions he was not to be interrupted, however loudly the heathen might rage in the anteroom. Meanwhile, throughout the day and in the evening the Chief of Staff and the Bureau Chiefs were of course demanding and receiving a full share of his time. In between he somehow managed to conduct an immense correspondence, the formal signing of the departmental mail sometimes taking the better part of an hour, and many of the letters and memoranda he must needs prepare himself being none too easy to compose. The sound of the Provost Marshal General’s crutches in the hall told us it was 10 P.M. We could almost set our watches by him, for Crowder (whose wounds, by the way, had been received not in battle but in falling from a Pullman berth) had promptly learned the value of a daily discussion on the problems of a nation-wide draft with this son of a Confederate soldier, who had been raised in a small town, whose student days had been passed in Baltimore and Lexington, and who for fourteen years had been a public officer in Cleveland.

As the long days succeeded one another there were occasional calls from President Wilson, who never announced his coming and never stayed long; and almost daily meetings with Secretary Daniels and other Cabinet officers. One day we would have a phalanx of college presidents, who saw their students melting away and who wanted their institutions taken over — or at least financed — as training camps. On another, a delegation from a city not necessary to name might come to challenge the authority of the War Department to mend their morals for them just because a divisional camp was to be established nearby. In this case the Secretary conceded that the point of law was well taken, and suggested the wholly unwelcome alternative of changing the location of the camp. On still another day our T.V.A. of today was, I remember, born in a discussion regarding the sources of power for a nitrogen fixation plant great enough to ensure an unlimited supply of explosives. Once the Secretary scandalized us by explaining in German the intricacies of the draft law to a delegation of Hutterian Brethren, an offshoot of the Mennonites. Another time former Secretary of State Elihu Root came to discuss the Mission to Russia. Officers ordered to France had to be slipped in secretly to say goodbye. I can recall taking the future Chief of Staff, General March, out on a balcony and in through a window of the Secretary’s private office. Then there were official receptions for generals and statesmen from overseas, conducted with the active and, to us juniors, not always welcome, advice and counsel of the State Department. The frequent meetings of the Council of National Defense also were held in Baker’s office and made cruel demands on his time, though they doubtless served their purpose. And, of course, there were many calls to take him outside of his office — Cabinet meetings, Congressional committees, visits to nearby training camps.

And this kind of thing went on all day and every day from eight-thirty in the morning until eleven at night (only two or three hours less on Sunday), but nothing that happened could ever ruffle the tranquillity of the Secretary. How the favorite disciple of the excitable Tom Johnson could maintain throughout the alarums and excursions of wartime Washington this calm imperturbability was beyond our comprehension.

During this period Baker made one hasty trip overseas. Though naturally different, his days there were just as strenuous as those in Washington. Our officers behind the lines were proud of the docks and warehouses and hospitals they were building, and those at the front wanted to show him the morale and appearance of their men. Their determination that the Secretary should see all with his own eyes meant long and arduous trips, between which must be found time for serious discussions. That these discussions were fruitful, we have the public evidence of General Harbord and Charles G. Dawes, Pershing’s right-hand citizen soldier; Sir Arthur Salter has told me that it was directly due to Baker’s quiet but effective presentation of the situation that the British Government diverted so large a proportion of their ships from highly profitable trade routes to transport our soldiers and supplies.

Slowly at first, and then with increasing rapidity, the picture at Washington changed. Into the service of the War Department itself, men of affairs, accustomed to making decisions rather than passing the buck, were being absorbed. Outside it, the direction of the various war boards and war administrations fell into competent hands. Other Federal departments, notably the Treasury, were strengthened by the acquisition of men of first-rate ability. As a result, the direct pressure of non-military matters upon the Secretary of War was correspondingly lightened, and he could concentrate his attention on the problems which came to him not via the public reception room but through the door connecting his office with that of the Chief of Staff.

Until the end of 1917, however, no clear distinction could be drawn in Baker’s daily work between his military and his civilian activities. He had, in fact, to stand between and, so far as possible, to reconcile two very different human attitudes. The military way of thinking and acting is based on long tradition; instinctively, it avoids lights and shades and doubts; while there might be private jealousies, the Army thought and acted essentially as a unit. The American people, on the other hand, were far from united in 1917. Many were definitely hostile to the whole enterprise, many more were at that time indifferent; certain elements were already outdoing Ludendorff himself in war spirit; very few had any conception of what war really meant. In the task of building up an Army the civilian attitude put much more emphasis than the military upon applications of new scientific knowledge, upon matters of comfort and health, physical and mental, and social and recreational services of all sorts. It recognized, as the Army did not at first, the repercussions upon civil life, that the War Department, for example, was becoming the country’s largest employer of civilian labor. It was the Secretary’s task to bring about a fusion of these two strains, and the degree of his success may be measured by the fact that the United States was able to build up a great Army, whose courage and endurance were beyond question, whose health record, despite the influenza epidemic, was extraordinary, and whose behavior was the best in the world’s history. Two years after the call which brought four million men to the colors, there were actually fewer soldiers in military prisons than there had been when that call was issued. It was, as well, an Army which it proved possible to reabsorb into civil life without undue confusion and difficulty.

Curiously enough, Baker the pacifist won the confidence of the Army officers before he enjoyed that of the public at large. Or perhaps this is not so strange after all. Few men in the Army or the Navy are militarists in the sense that our super-patriots deserve the title. It is no wonder that he and Tasker Bliss, scholar and philosopher as well as soldier, should achieve a prompt meeting of minds; but his success, though not so immediate, was equally complete with the more conventional type of professional soldier. Even before the outbreak of war the Bureau Chiefs with civilian responsibilities, men like McIntyre of the Insular Bureau and Black of the Engineers, had found him a Secretary after their own hearts, who had the brains and industry to understand the matter in hand, who in consultation with them would reach a decision, and having reached it would stay put. Of Crowder’s conversion I have already spoken, and we know that all these men passed the word along to their fellow officers in the combat branches who had not come into contact with the Secretary.

As to the civilian attitude, on the other hand, we had only to read the daily and weekly press (when we had the chance) to know that outside the Department there was widespread misunderstanding of the Secretary, and more than one center of implacable hostility. It was hard for us to judge whether the countless civilian visitors were exerting an influence in his favor, for, in general, after their visits they promptly left our sight. One very important type of civilian, however, remained under our observation. Baker was incredibly patient but quite firm with the members of Congress who wanted favors for constituents, and little by little it became recognized that though the Secretary’s quiet No might be disappointing, no one else would receive a different answer to the same question. In his relations with the two Committees on Military Affairs the picture is somewhat different. Here the Secretary, in his desire to defend his military associates from charges which he knew to be unfair, showed himself rather too skillful as a counsel for the defense to permit the establishment of an early entente cordiale. With the more thoughtful members, however, and notably with Senator Wadsworth and Representative Kahn, Republican leaders of Democratic committees though they were, a basis of mutual respect and confidence was established and maintained throughout the war.

The culminating event of this first period of Baker’s war administration was his account of his stewardship to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs on January 28, 1918 (twenty years ago, to the day, as this is being written). This was the occasion to which the anti-Bakerites had been looking forward in order to “get” the Secretary and force his resignation. Baker, be it said, recognized the good faith and patriotic motives of the great majority of his critics (there were exceptions to be sure, but these didn’t count in his mind). He himself was far from satisfied with the progress that had been made in certain essential services and, if it were made evident that a change in direction would be in the public interest, he was just as ready to step aside as when he had offered to resign his place in the Cabinet upon Wilson’s reelection. But his testimony revealed such an amazing grasp of the problem as a whole — and in all its parts — so clear a picture of pending difficulties and of the steps being taken to surmount them, that the more thoughtful of his critics saw at once that in going farther for a Secretary of War the country might well do much worse; and though criticism was to continue, this day marked the turning point in the civilian attitude.

At the time, as I have said, we knew only dimly and in part what kind of picture all these people who saw the Secretary of War were taking away with them — soldiers, legislators, scientists, professional and business folk of all sorts — how they described him to their wives that night. But in retrospect, and in the light of Baker’s later reputation, which must of necessity have been built up in large part on just this basis, I can, I think, present a pretty fair composite sketch.

His visitors arrived expecting to see a functionary, with all that this implies. They found a man short in stature, fragile in build, who never raised his voice in protest or command, never clenched his fist, never lost his temper. They found a man as completely selfless as it is possible for a human being to be, who instantly and instinctively assumed the other man’s sincerity of purpose. Needless to say, this led to occasional disappointments and disillusions, but these were rare and they never embittered his reception of the next visitor. A common meeting ground for discussion was promptly established, and a well-furnished mind, clarity of understanding, and an amazing power of exposition were placed at their service, and at their service as of right and not by favor. But there was, I am sure, something more than these recognizable and more or less measurable qualities to be reckoned with — something intangible, something rich and rare in the man’s personality which made his friendship a major event in one’s experience. When in the spring of 1917 Theodore Roosevelt referred publicly to Baker as “exquisitely unfitted to be Secretary of War,” he builded better than he knew in the selection of his adverb, if not of the word which followed it; “exquisite” is the mot juste to characterize that delicate combination of personal qualities which had so much to do with Baker’s power.

If I had to choose the one quality in his make-up which exercised the most potent influence upon soldier and civilian alike, it would be his courage, an undramatic but imaginative courage, broad enough to cover both a gallant recklessness and a philosophic fortitude. His effective support of the Selective Draft demanded that sort of courage, particularly from so recent a convert to its necessity. To set the pattern of American participation upon so vast and costly a scale took both imagination and courage. And certainly, to break all American tradition by giving the General in the field a free hand and protecting him from criticism meant both courage and fortitude. It was Pershing who kept Leonard Wood on this side of the Atlantic; it was Baker who silently received the resulting storm of protest.

The day-by-day administration of his office gave him many other opportunities to show his mettle. In the general confusion, Congress had adjourned in March 1917 without enacting necessary Army Appropriation Bills; yet for weeks the Secretary by “wholesale, high-handed and magnificent violation of law” (to quote Ralph Hayes) placed contracts for scores of millions of dollars without a vestige of legal authority. Later on, in the selection of officers to fill key positions in the United States, he bided his time, perhaps he overbided it; but when in his judgment the day had come to act, he acted with cool courage. To pass over the entire Quartermaster Corps with its special training, and to choose as Chief of Procurement a retired Engineer officer took courage, even though the man selected was the builder of the Panama Canal, George Goethals. Today it is no secret that in selecting Peyton March as Chief of Staff at a crucial moment the Secretary followed his personal judgment rather than that of his military advisers. March was recognized as a man of the first ability, but to say that he was not popular with his fellow officers is to put it conservatively, and it took something more than courage to make the appointment, for the Secretary quite accurately foresaw that thenceforth many things would be done not as he himself would do them, but in a very different fashion, and that his would be the task of binding the wounds to be inflicted right and left by a relentless Chief of Staff. There can be no question, however, that this selection, and the free hand he thereafter gave to March to reach his objectives in his own way, did much to hasten the termination of the war.

Let me give one final example of Baker’s fortitude. After the Armistice the President asked him to be a member of the Peace Commission, an invitation he would have rejoiced to accept, not only because he had something to contribute, but because he sensed, I feel sure, that his presence might have another value, for the President was always at his best with Baker. His clear mind realized, however, that his own war job was only half done, that two million men had to be looked after until they could be shipped back from France, and that these and two million others must be reabsorbed into civil life; there was no shade of hesitation or regret when once more he quietly said No.

It would be no kindness to Baker’s memory to maintain that there was no ground for criticism of his administration, and it would indeed ill become a member of his personal staff to do so, for in the earlier days we ourselves were critical enough. We loved him for his faults, but we were sure that the faults themselves were grievous: outrageous overwork; too much tobacco; hours spent in suffering fools, if not gladly, at least with reprehensible patience; over-consideration of the feelings of the unimportant; and, worst of all, a habit of watching and waiting and listening when the situation in our own judgment demanded a prompt and brilliant decision. It was only later on that we could see that his sense of timing was much better than either his friends or foes could realize. It was only in retrospect, too, that we could give him credit for the double gift, so rare in an executive, of leaving some things alone and of seeing that other things didn’t happen.

After the war there came four occasions for looking backward; each in its own way throws light on Baker’s reputation. The change in national administration in 1921 brought in its train the inevitable official inquiries which sought to find evidence of wrongdoing and particularly of corruption in the conduct of a war which had cost more than $1,000,000 an hour to conduct. The net result of the 37 charges considered by the War Transactions Section of the Department of Justice was two convictions and two pleas of guilty, all in relatively minor cases. As Mark Sullivan put it, “All the charges and all the slanders against Baker’s management of the war collapsed or evaporated or were disinfected by time and truth.” The next two occasions were more or less accidental, but none the less significant. The first was the appearance in the American supplement of the “Encyclopædia Britannica” in 1922, of a seemingly malicious article on Baker. He himself refused to get excited about the matter. In fact, he wrote to a friend: “I am not so concerned as I should be, I fear, about the verdict of history . . . it seems to me unworthy to worry about myself, when so many thousands participated in the World War unselfishly and heroically who will find no place at all in the records which we make up and call history.” His friends, however, rallied to his defense, and the result was a flood of published letters from men who knew at first hand of the Secretary and his work. A meeting of the American Legion in Cleveland in 1930 revealed his popularity with enlisted men as well as officers.

Finally in the preëlection year of 1931 there was the customary scanning of the horizon for presidential timber. Newton Baker was obviously in the line of vision, and there was much discussion of his qualifications. In these discussions it became clear that to some degree the sides had shifted: certain of his former liberal and radical supporters found the middle-aged lawyer with a large corporation practice wanting in qualities they had admired in Tom Johnson’s City Solicitor, and said so in the condescending style which reformers permit themselves. On the other hand, journals and writers that had been openly anti-Baker in 1917 came out strongly in his favor. Baker himself took no part in the proceedings. He hadn’t the slightest intention of going gunning for the nomination. Whether he would have accepted it had it been offered, I do not know. As a good party man, he might have done so, but on the other hand he had already had intimation that his heart had been seriously affected by the strain put upon it fifteen years earlier, and this might well have settled the question in his mind.

In writing for this quarterly, certainly, the question of Baker’s interest in foreign affairs must not be overlooked. In his university days he had been a student of history, and thereafter, no one knows how, he had kept up his reading. War itself is perforce an international enterprise, and to keep our forces in France together and under our own flag took constant and difficult diplomatic negotiations with our Allies. It is the general testimony that the leaders from other lands whom he met in Washington and elsewhere both understood and admired him, and I have a theory that one of the reasons, a reason of which he himself was quite unconscious, was that like Dwight Morrow of his own generation, like Irving and Hawthorne in the last century, Baker has his place in the line headed by Franklin and Jefferson, the line of those who stand as living demonstrations that one can be as authentically and refreshingly American as Uncle Sam himself, while at the same time conforming to the standards of quiet good manners and sharing la culture générale of the Old World.

But it must be added that in his relation to foreign affairs, as in other matters, Baker declines to be subdivided, even in retrospect. His internationalism is only one reflection, though an important one, of an underlying and indivisible faith in our common human nature and faith in the power of ideas. He was no more interested — and no less — in the problem of a coerced minority in the Danubian region than of the corresponding troubles of a Negro group in an American city. He would work with equal ardor toward a joint understanding between China and Japan, or to bring Protestants, Catholics and Jews together here at home.

To understand the years remaining to Newton Baker after he left Washington in 1921 one essential factor must be kept in mind. It would be easy to picture him as a professor in any one of half a dozen fields of scholarship, or as a diplomat, or editor, or executive; but his choice of the law as his life-work, made as a very young man, was as authentic a “call” as any man has ever had to the ministry. He had scarcely started on its practice, however, when he was drawn into the public service, in which he was to remain with hardly a break for a score of years. His return to Cleveland was above all a return to his first love. There was no lack of reciprocal affection on the part of the law, and as a result all his other activities were conditioned upon having to fight for the time he could devote to them.

That his mind was constantly at work upon questions of peace and war there is abundant evidence. Take for example the following passage from his Memorial Address at Woodrow Wilson’s tomb in 1932:

The conference at Paris demonstrated that the sense of victory does not create a favorable atmosphere for the construction of just and enduring peace. The portions of the Treaty of Versailles that were dictated by the spirit of victory are largely the parts of that treaty which still obstruct peace. Nations, like men, have emotions, are sensitive to hurts to their pride, and in moments of passion submerge their better selves.

The only sort of peace which can endure must come from a recognition of virtues as springs of national action as well as guides for individual behavior. The future peace of the world cannot be secured by processes which attain diplomatic successes and inflict diplomatic defeats, which inflame nations with a sense of aggrandizement or humiliate them with a sense of wounded pride.

And somehow he found time to do not a little serious writing. In “War and the Modern World,”[ii] the memorial lecture for 1935, he paid the boys of Milton Academy the compliment of giving them his best. “Why We Went to War,” first published in this review,[iii] was really a tour de force, of which he himself was naively proud. The outward and visible sign of this self-challenge to do a thoroughly scholarly job despite an overwhelming pressure of other tasks was a second desk moved into his office, and piled high with volumes and reports. How and when he found the time to digest the material and write the treatise remains a mystery.

I shall not enumerate his services on national commissions or on private boards, educational, philanthropic and professional, except the Wickersham Commission of 1929, and those on Unemployment Relief in 1930, and on the Army Air Corps in 1934. They drew heavily upon energies which by this time it was all too evident he should have been conserving.

No man in his senses would add all these things to the engrossing demands of an active law practice; but then I am not maintaining the thesis that he had any sense — about himself. He didn’t, and there was nothing to do about it. Those of us who, following a British precedent, had organized a Society for the Preservation of Newton Baker, got no coöperation whatever from the subject of our solicitude, and we decided before long that the pain of refusal might really be worse for him than the additional strain of acceptance. From time to time during the last few years he did give up some voluntary service, and made a great virtue of it, but he never failed to replace this by at least two others.

Before the reader lays down this article, I should like him to know that it is not what I myself had meant it to be — namely, an appraisal of a public service, sympathetic naturally, but dispassionate. It has turned rather into a tribute of personal affection. All I can say in extenuation is that the very same thing would have happened had the editor of FOREIGN AFFAIRS selected for the task any other of Baker’s associates.

[i] New York: Doran, 1918.

[ii] Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935.

[iii] FOREIGN AFFAIRS, v. 15, n. 1. Later published as a book by the Council on Foreign Relations.

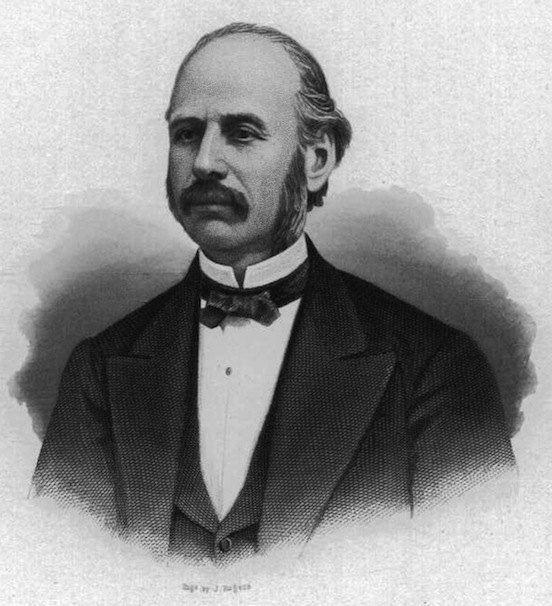

The Heart of Amasa Stone by John Vacha

THE HEART OF AMASA STONE

By John Vacha

On the afternoon of May 11, 1883, the usual decorum of Cleveland’s “Millionaires’ Row” was barely disturbed by a single muffled gunshot. It came from the rococo mansion of industrialist Amasa Stone. Entering an upstairs bathroom, a servant discovered the master of the house lying partly dressed in the bathtub, a .32 revolver by his side and a bullet in his heart. There were some unforgiving souls who thought it should have been done half a dozen years earlier.

One of his contemporaries was reputed to have predicted that while Stone may have been the richest man in the city, he would have its smallest funeral. He left an estate estimated at $6 million. His family, unwilling perhaps to risk fulfilling the second half of that prophecy, restricted his burial service at Lake View Cemetary to relatives only.

Except for one tragic miscalculation, Stone by most measures left behind a lifetime of enviable achievement. He had built and run some of Ohio’s principal railroads. His business ventures in railroads, banking, and manufacturing gained him one of the great fortunes in an age of great fortunes. Cleveland had gained its preeminent institution of higher learning largely at his behest, and his two daughters enjoyed well-connected marriages.

As did so many early Clevelanders, Stone came to the Western Reserve from New England. He brought skills highly in demand for a growing city, having experience in engineering and construction. In fact, there was already a job waiting for him in the Forest City.

Amasa Stone, Jr., was born in 1818, the ninth of ten children of Massachusetts farmers. Those siblings provided him with two rungs on what a nineteenth- century Currier & Ives print depicted as “The Ladder of Fortune.” He left farm work behind when seventeen to begin an apprenticeship in construction with his older brother, Daniel. Within two years he was able to buyout his apprenticeship and set about building homes and churches on his own.

By 1840 Stone joined his brother-in-law, William Howe, inventor of a unique bridge truss designed to support heavy loads over short spans. They employed it to construct the first railroad bridge over the Connecticut River. Stone soon purchased the patent rights to the Howe truss for all New England and corrected a suspected weakness in its design. His reconstruction of a hurricane-destroyed bridge across the Connecticut River in only forty days cemented his reputation as New England’s foremost railroad contractor.

Within another year, Stone was setting his sights westward beyond New England. He formed a partnership with Frederick Harbach and Stillman Witt to

build the northern half of the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad. It had been an ill- starred venture originally chartered in 1836 but almost immediately stunted in the cradle by the Panic of 1837. In order to keep their charter from being revoked, its directors at one point had resorted to the expedient of employing only a single worker with a shovel and wheelbarrow on the right-of-way.

Harbach, Stone, and Witt undertook to complete the troubled CC&C Railroad, taking part of their compensation in the form of stock. Because of the risk, they were able to demand a higher than normal fee, betting in effect on the road’s success and the resultant growth of Cleveland. The Cleveland to Columbus leg was opened on February 17, 1851. It proved an instant success and provided the basis of its makers’ fortunes.

“An industrial empire was in the making south of the Great Lakes; Cleveland was one of its centers; and Amasa Stone was one of the empire builders,” noted one historian. Stone was offered the position of superintendent of the CC&C at a salary of $4,000. He and his two partners then proceeded to build the Cleveland, Painesville, and Ashtabula Railroad, a job completed in 1852. Stone was a director on the boards of both roads and became president of the CP&A in 1857.

Stone had brought his family to Cleveland in the spring of 1851. With his wife, the former Julia Gleason, it included a son, Adelbert, and daughter Clara. Another daughter, Flora, was born shortly afterward. They became members of the prestigious First Presbyterian (Old Stone) Church on Public Square. In 1858 Stone manifested his position among the city’s elite by building an imposing new mansion on Euclid Avenue–one of the earliest residences on what would become nationally celebrated as “Millionaires’ Row.”

With all his construction experience, Stone naturally took a hand in the building of his own home. Underneath all the inevitable gingerbread of the Victorian era– bays and balustrades, corbels and belvederes–it rested on the Outer stolid, practical values of a self-taught engineer. Outer walls nearly two feet in width were insulated by an eight-inch hollow space between their inner and outer surfaces. A reputed 700,000 bricks went into the rearing of the structure. Running water, gas fixtures, and central heating were among its modern amenities. Stone’s library, dedicated more to business than to books, featured a fireproof recess for his desk, papers, and safe.

To all outward appearances, the Stone mansion conformed to the Italianate Villa style dominant along early Millionaires’ Row. A grand central hallway divided the formal from the family rooms, all finished with paneled ceilings, rosewood or oak doors, and fireplace mantels of Vermont marble. All was unveiled to the city’s fashionable set, and “old settlers” as well, at a housewarming hosted by the Stones early in 1859.

Stone meanwhile was broadening his business ventures in railroads and other fields. He built the Michigan Southern road, which was later linked with the CP&A as the Lakeshore Railroad. Together with several other business leaders he built the short but vital Cleveland and Newburgh line to service Cleveland’s burgeoning industrial valley. One of those nascent industries was the Cleveland Rolling Mill, in which Amasa was an investor and his brother Andros president. Amasa Stone also invested in the Western Union Telegraph Company being organized by Clevelander Jeptha Wade. He was a director of several banks and president of the Second National Bank, giving him an influential voice in the growth of the region’s industries.

By the time of the Civil War, Stone was clearly one of his city’s movers and shakers. Abolitionist in sentiment, he had supported the nomination of Abraham Lincoln by the Republicans in 1860. When Lincoln stopped in Cleveland on his way to Washington the following year, eight-year-old Flora Stone greeted the President- elect with a bouquet of flowers. With the coming of war, Lincoln turned to her father for assistance with problems of military supply and transportation.

On the home front in Cleveland, Stone joined a committee to distribute relief funds for the families of local Union volunteers. When recruiting fell off later in the war, he recommended that another committee be formed to raise $60,000 for bounties to encourage volunteers and thus spare Cuyahoga County from subjection to the military draft. He was an active supporter of Union candidate John Brough for governor in 1863, ensuring Ohio’s continued support for the war.

About the only thing Stone begrudged the Union cause was the service of his only son. Described as personable and unassuming, Adelbert Stone was an ardent Republican in sentiment with a strong desire to enlist in the Union Army. His father was grooming him for better things than cannon fodder, however, and decreed that “Dell” should go to Yale instead to study engineering. Weeks after the last guns of the Civil War were silenced, a telegram from Yale informed Stone of the death of his son. While on a geological field trip, he had drowned in the Connecticut River, scene of his father’s early exploits.

Of heavyset build, with a straight, well-formed nose and full mustache and beard trimmed to medium length, Stone projected an appearance that brooked no opposition. His eyes were deeply set under heavy brows and a receding hairline. “Stone was never constitutionally fit to accept domination for he considered dominion to be his own prerogative,” wrote his biographer. As president of the Lakeshore Railroad, he had insisted on using an iron Howe truss manufactured by the Cleveland Rolling Mill, to replace the bridge at Ashtabula. When advised by an engineer that the beams were inadequate for the length of the span, he got a new engineer and did it his way.

Stone’s leadership was evident in Cleveland’s civic as well as business affairs. He presided at the banquet to celebrate the opening of a new Union Depot on the lakefront, which he had helped design and build. He and Wade led in the incorporation of the Northern Ohio Fair Association to promote agriculture, industry, and, incidentally, trotting races. He joined other investors in the founding of the Union Steel Screw Company, which pioneered in the manufacture of wood screws from Bessemer steel. One of his principal charitable projects was the establishment of the Home for Aged Protestant Gentlewomen.

With the marriage in 1874 of his older daughter Clara, Stone acquired a son-in- law to compensate in part for the loss of his natural son. John Hay had already distinguished himself as a writer, diplomat, and secretary to Abraham Lincoln. Stone built a mansion for Clara and her husband next door to his own on Millionaires’ Row, telling neighbors with heavy-handed jocularity that he was “building a barn for his Hay.” Later Hay would employ the gift to host a celebrated reception for Ohio-born writer William Dean Howells, inviting his father-in-law to mix with such luminaries as President Rutherford Hayes and General James Garfield. Stone’s younger daughter Flora did as well as her sister, marrying the rising Cleveland industrialist Samuel Mather. Stone seemed to have scant social life outside of family and business, however. For the most part it consisted of quiet dinners and evenings with such neighbors and business associates as John and Antoinette Devereux.

Outside that close circle of family and friends, Stone cut a far from popular image in Gilded Age Cleveland. “Almost everybody feared Stone’s arbitrary ways, his harsh temper, and his biting tongue,” wrote the historian on Case Western Reserve University, who provided a possibly apocryphal but nonetheless revealing illustration. No love was lost between the sponsors of the originally separate institutions, Stone and Leonard Case, Jr. A single tract of land was to be divided between Case School of Applied Science and Stone’s legatee, Western Reserve College. Case preferred the western half, but knowing his antagonist, let out that he wanted the eastern section. The ploy worked: Stone insisted on the eastern half for Western Reserve, and Case thus acquired his real if unspoken preference.

One local businessman who managed to resist the habitual command of Stone was young John D. Rockefeller. Stone had been an early investor in Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company and a director of the Lakeshore Railroad when it granted Rockefeller secret rebates, which led to Standard’s dominance in the fledgling oil industry. As a member of Standard’s board, however, Stone assumed elder statesman airs which Rockefeller, twenty years his junior, found irksome. When Stone asked for an extension after letting an option to buy additional stock expire, Rockefeller refused to grant the favor. Thus affronted, Stone sold off his previous holdings; Standard survived and prospered nonetheless.

On top of that private rebuff, Stone suffered an even greater public humiliation. During a raging blizzard on the night of December 29, 1876, a westbound Lakeshore train approached the bridge over the Ashtabula Creek gorge — the same one Stone had built against the advice of his engineer. Only the lead locomotive made it to the other side. As the span collapsed, the second locomotive and eleven cars with 164 passengers and crewmen plunged seventy feet into what one newspaper headlined as “The Valley of Death!” Those not killed in the fall were exposed to fires started by the stoves in the passenger cars. Only eight escaped injury, and the death toll reached eighty-nine.

There were numerous post-mortems on the disaster. An Ashtabula County coroner’s jury, while paying lip service to his good intentions, placed primary responsibility directly on Stone. Also held responsible, for failure to adequately inspect the bridge, the Lakeshore Railroad was assessed for damages of more than half a million dollars. Another investigation was undertaken by a joint committee of the Ohio General Assembly. In consideration of Stone’s health, they questioned him in his personal library. Against at least one eyewitness account, Stone maintained that the bridge’s failure was due to the train’s derailment. The committee was less easy on the road’s chief engineer, Charles Collins, who had deferred to Stone on the bridge’s construction but admitted under intense questioning that he had never closely inspected the structure afterwards. Only hours after the hearing, the distraught Collins took a revolver and committed suicide. (It was the right thing to do, concluded many, but the wrong man had done it.) Stone, an object of general vilification, sought refuge in a trip to Europe.

Some believed that Stone had never recovered from the death of his son; most certainly, he never recovered from the opprobrium of the Ashtabula Bridge disaster. In addition to those afflictions, he was also plagued by business worries. Nationwide strikes broke out while he was in Europe, including employees of his Lakeshore Railroad. He couldn’t have been reassured by news from his son-in- law John Hay in Cleveland that “Since last week the country has been at the mercy of the mob. The town is full of thieves and tramps waiting and hoping for a riot, but not daring to begin it themselves.”

Following his return, Stone embarked on the principal benefaction of his civic career. In 1880 he offered half a million dollars to Western Reserve College in nearby Hudson, Ohio, on condition that the college relocate to Cleveland. He also called upon other Clevelanders to provide grounds for the campus. As a memorial to his son, he specified that the school should alter its name to Adelbert College of Western Reserve University, although the university historian, C.H. Cramer, speculated that the underlying real reason for the gift was “the necessity for some kind of propitiation” for the Ashtabula Bridge tragedy. Together with the simultaneous establishment of the Case School of Applied Science, Stone’s gift provided the foundation for what ultimately became known as University Circle.

Undoubtedly, the memorialization of his son was the last bit of satisfaction Stone was able to squeeze out of life. He had resigned from the board of the Lakeshore Railroad following its absorption by the Vanderbilt railroad interests, unable, as his biographer put it, to “withstand the transfer of major command decisions from Cleveland to the Vanderbilt offices in New York City.” Strikes had broken out at the Cleveland Rolling Mill in 1882, and several midwestern steel companies in which he was involved had failed. His health broke down completely under these stresses and whatever internal demons tormented him.

“I have not been to my office for some time,” Stone wrote to Hay, who was in Europe himself at the time. “Nervous frustration seemed to be my first misfortune and sleeplessness has followed.” Two weeks later, following yet another night of insomnia, he took his revolver into the bathroom and finally was able to find rest.

Stone’s widow and daughters devoted a considerable part of their inheritance towards redeeming the magnate’s reputation. Two years after his suicide, they donated John LaFarge’s Amasa Stone window to the restored sanctuary of Old Stone Church, following the fire of 1884. In 1910, the year the Stone mansion on Millionaires’ Row was torn down to make way for a Euclid Avenue department store, they provided for the erection of Amasa Stone Chapel on the campus of Western Reserve College, adjacent to the college’s Adelbert Main Building. From Stone’s old Union Depot, they salvaged a carving of Stone’s head and incorporated its stern image into the façade of the Gothic structure. They set it above the eastern portal, facing away from the old Case campus.

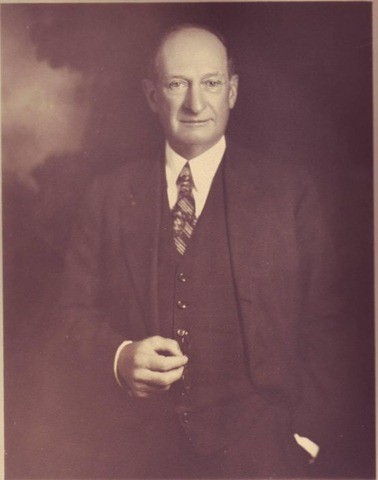

Maurice Maschke – The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland by Brent Larkin

Maurice Maschke – The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland

by Brent Larkin

More than 75 years after his death, memories of Maurice Maschke linger still in the minds of the precious few who remember a political boss whose power influenced almost every aspect of life in Cleveland.

“I was a young boy who grew up in his neighborhood,” Forest City Corp. executive Sam Miller recalled of the legendary Republican leader. “I remember well he was the person everyone went to if they wanted something done.”

Hall of Fame journalist Doris O’Donnell’s mother was a Democratic ward leader for party boss Ray T. Miller – Maschke’s longtime political rival.

“On Sundays, we had these large family dinners at our home in Old Brooklyn and invariably there would be talk about city politics, about Miller and Maschke,” said O’Donnell. “They were both very competitive – and very smart.”

Longtime Ohio Republican Party chair Bob Bennett cut his teeth in Cleveland politics during the 1960s. Back then, Bennett said the Republican old timers regularly spoke of Maschke in reverential terms.

“He set the standard for political bosses, for how to obtain power and use it effectively,” said Bennett. “He made things happen. And, most importantly, he knew how to choose the right candidates and win elections. After all, that’s what politics is all about.”

It is indeed.

And no one in Cleveland ever did it better than Maurice Maschke.

****************************

Born in Cleveland in 1868, Maschke grew up in the predominately Jewish neighborhood of lower Woodland Ave., a few miles southeast of downtown.

The son of a relatively successful grocer, Maschke was a bright young boy – so bright he was schooled at the prestigious Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and Harvard University near Boston.

Graduating from Harvard in 1890, Maschke returned to Cleveland where he studied to be a lawyer. While reading law, he landed a job as a clerk in the county courthouse, a place teeming with aspiring politicians.

It was around this time that Maschke befriended Robert McKisson, a rising star in city politics. Maschke signed on as a precinct worker in the McKisson political organization. In 1894, McKisson was elected to City Council. A year later, he was elected mayor.

That election increased Maschke’s stature within the Republican Party. And it enabled him to secure an important job in the county recorders office.

Maschke, it seemed, was on his way.

But McKisson soon clashed with Marcus Hanna, the Cleveland industrialist who in 1900 would engineer William McKinnley’s election as president. Hanna was, at the time, the nation’s most powerful political insider and McKisson’s falling out with Hanna contributed to his defeat in the mayoral election of 1899.

That defeat could have slowed Maschke’s political ascent, but by then the young East Sider no longer needed the support of a powerful political patron. He had figured how to advance on his own.

Maschke formed an alliance with Albert “Starlight” Boyd, the city’s black political boss, that served them both well. He also befriended Theodore Burton, an ambitious young congressman with a big Republican following.

In 1907, Burton unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Mayor Tom L. Johnson. But in early 1909, the legislature appointed Burton to the U.S. Senate. Maschke became Burton’s political eyes and ears back home.

Many now considered Maschke the city’s most powerful Republican operative. Later that year, he would prove them right.

After eight years in office, Tom L. Johnson had won the reputation as perhaps the nation’s greatest big city mayor. To this day, the progressive Democrat is revered for building an affordable, citywide transit system, providing low-cost electricity to residents through construction of a municipal light plant, and the opening of dozens of new parks.

But as the 1909 election approached, Maschke boldly predicted he had a candidate who could beat Johnson. Most regarded the claim as political puffery – especially when they heard Maschke’s candidate was Herman Baehr, the bland and inarticulate county recorder.

Nevertheless, Maschke was adamant. “Baehr will win,” he insisted. “Johnson has been mayor for eight years. That’s too long.”

True to form, Baehr proved to be a horrible campaigner. Johnson was so unimpressed by his opponent that, three days before the election, he left town.

He should have stayed. On Election Day, Baehr won decisively. Maschke, who became county recorder when Baehr vacated the job, was now the town’s preeminent political figure.

Next, Maschke would take his act to the biggest political stage of all.

At the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, President William Howard Taft was challenged by former President Theodore Roosevelt. As the convention opened, it appeared Taft had squandered his incumbent’s advantage – losing 9 of the 12 statewide primaries to Roosevelt, including his home state of Ohio.

But 100 years ago party bosses had a greater say in the presidential nominating process than rank and file voters. And in Chicago that year, perhaps no party boss had more clout than the Republican from Cleveland. When the roll was called, Maschke played a key role in Taft’s nomination.

That November, Taft lost the general election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, but not before he appointed Maschke to the coveted post as Northeast Ohio’s customs collector. It was Boss Maschke’s last public job.

****************************

By 1920, Maschke had formally taken charge of the entity he had, in actuality, controlled for a decade – the county Republican Party. He had also established a law firm, that would eventually make him a wealthy man.

In 1924, Cleveland switched to a city manager form of government – with the job being filled by William Hopkins, Maschke’s close friend. Hopkins was charismatic and visionary. He championed construction of a huge stadium on the lakefront and purchased land from Brook Park to build an airport.

But Cleveland’s population was changing. A steady influx of European immigrants added to the Democratic Party’s growing numbers. And Democratic Party chair Ray T. Miller, who doubled as county prosecutor, was shrewdly taking advantage of that growth.

Compounding Maschke’s political problems were corruption charges – and some convictions – of Republican party operatives. Maschke himself was charged for his alleged role in a scandal involving county government. But the case against him was weak, and Maschke was acquitted.

Nevertheless, criticism of the chairman was growing – even from some Republicans. Near the end of the 1920s, Maschke’s power at home was waning.

But on the national stage, Maschke summoned up one more grand performance. In 1928, he was a leading supporter and valuable political strategist to Herbert Hoover’s successful presidential campaign.

Once again, Maschke had a friend in the White House. At home, however, problems continued.

But by the late 1920s, Maschke and Hopkins had a huge falling out. Some speculated Maschke resented Hopkins’ popularity. Another theory held Maschke thought Hopkins didn’t do enough to support Maschke’s friends, the Van Sweringen brothers, during construction of the Terminal Tower.

Whatever the cause of the rift, Maschke, as usual, prevailed. In 1930 members of City Council, saying Hopkins had become power-hungry, fired him. Not long after, during an appearance at the City Club, Maschke said he had merely “put Hopkins back on the street where I found him.”

*********************

It is fair to wonder how Maschke, a Jew in a city where Jews represented only a fraction of the population, was able to dominate city politics for more than a two-decades-long period. The answer requires some educated speculation, but the answer is probably a combination of some or all of these factors:

Maschke’s religion was probably unknown to many, as it was hardly a common Jewish surname. What’s more, at the time, Republican rank and file were viewed as more progressive and open- minded than their working class Democratic counterparts.

And since Maschke never sought high office, his religion and ethnicity was never really a factor with the electorate. Had he run for congress or mayor, voters might have paid more attention to his background and beliefs.

Then, as now, results are what matter most to candidates and party operatives.

Maschke, however, was hardly the first political boss who was intelligent and understood how to win elections. What differentiated him from the others was his civility, honesty, perhaps even a sense of decency.

On that night of Maschke’s death, Roelif Loveland, considered one of the two or three greatest Cleveland journalists of all time, wrote of Maschke:

“To think of him – and we who knew him are not likely to forget him in a hurry – to think of him is to think of a man who was kind and gracious; who loved this city and his family and his party and truth and personal decency. To be sure, he gave the city about what its citizens wanted. If they wanted the town cleaned up, it was cleaned up. If they wanted it less rigid, it was less rigid.”

For all of Maschke’s endearing traits, what differentiated him from so many in public life was the well-rounded nature of his life. In the very first paragraph of an editorial following his death, the Plain Dealer noted his enormous political accomplishments, but also noted Maschke was a cultivated gentleman with many friends, lover of the classics, expert at bridge, devotee of golf – a polished, suave and delightful personality.

Maschke was hardly Cleveland’s last successful political boss. Nor is he the most renowned. That title probably belongs to Marcus Hanna.

But, for a time, Maurice Maschke probably accumulated and wielded more political power than any local leader before or since.

When he died of pneumonia on Nov. 19, 1936, the Plain Dealer’s coverage included 10 front page photographs and an obituary that started on Page One and ran for five pages inside.

In his tribute, Roelif Loveland recalled that during tense moments on election nights Maschke would seem to sometimes growl at his assistants.

“They pretended to be frightened” wrote Loveland. “But they weren’t.” Why?

“Because they loved him.”

To read more about Maurice Maschke, click here

Brent Larkin joined The Plain Dealer in 1981 and in 1991 became the director of the newspaper’s opinion pages. In October 2002 Larkin was inducted into The Cleveland Press Club’s Hall of Fame. Larkin retired from The Plain Dealer in May of 2009, but still writes a weekly column for the newspaper’s Sunday Forum section.

2015 State of the State Speech

2015 State of State Speech: Video (Ohio Channel)

2015 State of State Speech: Text (Associated Press)

Cleveland’s Chinese from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Cleveland’s Chinese from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

CHINESE. Cleveland’s Chinese population began to grow only after the 1860s. However, their numbers were small; in 1880 they were counted in the census with the Japanese, totaling 23. The 1890 census showed 38 Chinese, and by 1900 their number exceeded 100. The settlers were all Cantonese–from China’s southern province of Guangdong (Kwangtung), of which Canton, now Guangzhou, is the capital. The southerners among the Chinese were more ready to venture out of the country, and had migrated to all the countries in Southeast Asia and to Australia and New Zealand. The Chinese who settled in Cleveland did not come directly from China but moved here eastward from the West Coast. Their first settlement was on the street west of Ontario St., now W. 3rd St.; then they occupied a row of brick buildings on Ontario St. between PUBLIC SQUARE and St. Clair Ave. Wong Kee, who moved here from Chicago, opened the first Chinese restaurant at 1253 Ontario St., and later a second restaurant, the Golden Dragon, on the west side of Public Square. Most of the Chinese were proprietors of restaurants, waiters and cooks, or operators of laundries. Chinatown was a society of single men, as the 1882 Chinese Act barred them from bringing wives and children from China.

Even though they were a small colony, the Chinese established 2 merchant associations, the ON LEONG TONG and the Hip Sing Assn. Affiliates of national associations, these were societies of merchants engaged in mutual aid, self-discipline, matching funds and investment opportunities, and dispute reconciliation. The two associations were competitive, and at times their rivalry took violent forms. The associations were called tongs in Chinese, so their fights and killings were referred to as “TONG WARS.” In the late 1920s, as merchants needed the central sites around Public Square for major buildings, some of the Chinese moved east around E. 55th St. at Cedar Ave. and Euclid Ave. Eventually, in the early 1930s, the Chinese colony settled around Rockwell Ave. and E. 21st St. By then the Chinese population had grown to 800. In 1930 the On Leong Tong, the larger of the 2 associations, moved into new headquarters at 2150 Rockwell Ave. Since 1930, the block on the south side of Rockwell Ave. between E. 21st St. and E. 24th St. has been Cleveland’s Chinatown. Among Chinatowns of American cities, Cleveland’s is very small. By 1980 2,000-2,500 Chinese were living there. In the 1980s there were 3 Chinese restaurants and 2 Chinese grocery stores on this block. Next to one of the restaurants, the Shanghai, stands the On Leong Assn. Bldg. On the 3rd floor is the On Leong Temple, which is used for (Buddhist) worship a few hours a week, but more often serves as a meeting hall. The Sam Wah Yick Kee Co., the larger of the grocery stores, in its heyday delivered merchandise to 50 Chinese restaurants in Greater Cleveland and about 30 more downstate and around Pittsburgh.

From its beginning, the Chinese community maintained many Chinese values and traditions. They celebrated festivals on the Chinese calendar, most prominently the Chinese New Year in February. The Chinese were attached to their country of origin. Early in 1911 Dr. Sun Yat-sen stopped at Cleveland on one of his worldwide tours and spoke at Old Stone Church. Meetings were held at the Golden Dragon Restaurant on Public Square to rally support and to raise funds for his revolutionary movement to overthrow the rulers of the Qing (Ching) Dynasty. On 11 Feb. 1912, 4 months after the founding of the Republic of China, a celebration was held at Old Stone Church and a telegram of congratulations was sent in the name of the Chinese residents of Ohio to Dr. Sun, president of the Chinese Republic. Twenty-six years later, the Chinese were again active in fundraising to support the war effort and civilian relief in the Sino-Japanese War. They rallied behind the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Assn., the Cleveland Chinese Student Club, and later the Chinese Relief Assn. About 500 Chinese residents pledged $3,000 a month. From 1937-43 $180,000 was donated for food, clothing, and medicine. In July 1938 the Cleveland Chinese Student Club published a quarterly, the Voice of China. Its editorials and articles strongly criticized the U.S. policy of selling scrap iron and oil to Japan; pointed out the weakness of the Neutrality Act; and urged the public to boycott Japanese silk. Three Caucasian Clevelanders served along with 4 Chinese on the editorial board. Sentiments toward the Chinese among segments of Americans had been changing, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed in 1943.

The Chinese population increased by about 100 between 1930-60. The 1960 census reported 905. After 1960 there was an influx of Chinese from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Some of the young Chinese who came to the U.S. in the late 1940s and early 1950s for university studies chose to stay permanently and were now establishing families in all parts of Cleveland and the suburbs. Beginning in the late 1970s, a small number of engineers and scientists from the People’s Republic of China came to Cleveland for graduate study, and these increased to over 100 at CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY after 1980. In 1990 the census estimated that 985 Chinese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong immigrants resided in Cleveland proper. The new residents came from central and northern China and diluted the Cantonese concentration of the earlier settlers. Together with the offspring of the Chinatown residents, mostly college-educated, they advanced into the professions of engineering, medicine, and the sciences. The faculties of BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE, Western Reserve Univ., Case Institute of Technology, and other colleges in Cleveland had increasing numbers of Chinese in their ranks. In the 1950s the active mainstream of the Chinese population in Cleveland was the membership of the Chinese Students’ Assn. of Cleveland. As the students completed their studies and advanced in their professions, they changed their organization in the 1960s to the Chinese Student & Professional Assn. of Cleveland, and in 1977 adopted the name Chinese Assn. of Greater Cleveland.

One institution in Cleveland that worked with the Chinese from the time of their early settlement was the Christian church, specifically Old Stone Church. For 50 years, starting from 1892, the church conducted a Sunday school for the Chinese, teaching them English and the Gospel. The church viewed its work as a mission comparable to that carried out by the missionaries it sent to China. Instrumental in this work were 2 members of the church, Marian M. and Mary F. Trapp, sisters and public-school teachers who worked for 30 years among the Chinese residents living near the church. The sisters obtained a working knowledge of Chinese (Cantonese) and assisted the Chinese in business problems and other matters. In Dec. 1941, with the support of the Cleveland Church Fed., Old Stone Church, and First Methodist Church, a Chinese Christian Ctr. was established in EUCLID AVE. BAPTIST CHURCH. Language classes, worship services, and youth activities were transferred from Old Stone Church to the center. Dr. Wm. Fung came to Cleveland to serve as director, and his wife, Shao-ying Fung, assisted in teaching classes. In 1948 Dr. Fung was succeeded by Rev. In Pan Wan, a Baptist minister. The center’s activities were continued until 1953, when Rev. Wan left. Language classes were conducted periodically at Euclid Ave. Baptist Church in the late 1950s, and Bible studies were held in homes.

In the early 1960s the Protestants among the Chinese were meeting in homes for prayers and Bible study. In 1965 their representatives appealed to Rev. Lewis Raymond, pastor of Old Stone Church, and obtained the free use of the church’s facilities. Sunday worship services in Chinese and Bible classes began at Old Stone on 12 June 1966 and the Cleveland Chinese Christian Fellowship was born. The Fellowship became the Cleveland Chinese Christian Church in 1975, having called Rev. Peter Wong to be its pastor. The average number of worshippers on Sundays rose to 110 by the end of the decade. In 1983 the church moved to its own sanctuary building at 474 Trebisky Rd. in RICHMOND HEIGHTS With membership grown to 200, the church added an annex housing classrooms and a gym in 1994. Outside of the Chinese Christian Church, Chinese Protestants worshipped at various denominational churches in Greater Cleveland. The number of Roman Catholics among the Chinese is estimated to be about 20-25% of that of Protestants.

With the growth of the Chinese community in the 1960s, the movement to preserve Chinese cultural values became strong. In 1966 the Chinese Academy was formed on the east side to give Chinese children instructions in the Chinese language and history on Saturday mornings. After using the facilities of two churches in CLEVELAND HEIGHTS, the academy settled at Noble Rd. Presbyterian Church in 1973. In 1980 Chinese residents in the west and south sides started the Academy of Chinese Culture, and since 1981 it had made use of rooms in schools and churches in STRONGSVILLE during weekends to conduct classes for children. Peter C. Wang, founder of the Chinese-American Cultural Assn. in 1961, offered tuition-free classes in Chinese in public libraries to those interested throughout the 1960s. In 1975 Laurence Chang wrote and produced 2 1-hour TV programs on “Values and Institutions of Chinese Culture,” which were broadcast over WVIZ (Channel 25). Through these activities Clevelanders gained broader views of China and Chinese culture. A symbol of the Chinese presence in Cleveland is the marble garden with a bronze statue of Confucius in the center, a gift to Cleveland from the City of Taipei, Taiwan, which was dedicated as part of the CULTURAL GARDENS in Wade Park on 21 Sept. 1985. The China Music Project, started in 1980, continued to bring to Cleveland musicians from Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong and present them in concerts of traditional Chinese music.

K. Laurence Chang

Case Western Reserve Univ.

Fugita, Stephen, et al. Asian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland (1977).

Last Modified: 11 Jul 1997 01:30:56 PM

Cleveland’s Chinese from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Cleveland’s Chinese from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

CHINESE. Cleveland’s Chinese population began to grow only after the 1860s. However, their numbers were small; in 1880 they were counted in the census with the Japanese, totaling 23. The 1890 census showed 38 Chinese, and by 1900 their number exceeded 100. The settlers were all Cantonese–from China’s southern province of Guangdong (Kwangtung), of which Canton, now Guangzhou, is the capital. The southerners among the Chinese were more ready to venture out of the country, and had migrated to all the countries in Southeast Asia and to Australia and New Zealand. The Chinese who settled in Cleveland did not come directly from China but moved here eastward from the West Coast. Their first settlement was on the street west of Ontario St., now W. 3rd St.; then they occupied a row of brick buildings on Ontario St. between PUBLIC SQUARE and St. Clair Ave. Wong Kee, who moved here from Chicago, opened the first Chinese restaurant at 1253 Ontario St., and later a second restaurant, the Golden Dragon, on the west side of Public Square. Most of the Chinese were proprietors of restaurants, waiters and cooks, or operators of laundries. Chinatown was a society of single men, as the 1882 Chinese Act barred them from bringing wives and children from China.

Even though they were a small colony, the Chinese established 2 merchant associations, the ON LEONG TONG and the Hip Sing Assn. Affiliates of national associations, these were societies of merchants engaged in mutual aid, self-discipline, matching funds and investment opportunities, and dispute reconciliation. The two associations were competitive, and at times their rivalry took violent forms. The associations were called tongs in Chinese, so their fights and killings were referred to as “TONG WARS.” In the late 1920s, as merchants needed the central sites around Public Square for major buildings, some of the Chinese moved east around E. 55th St. at Cedar Ave. and Euclid Ave. Eventually, in the early 1930s, the Chinese colony settled around Rockwell Ave. and E. 21st St. By then the Chinese population had grown to 800. In 1930 the On Leong Tong, the larger of the 2 associations, moved into new headquarters at 2150 Rockwell Ave. Since 1930, the block on the south side of Rockwell Ave. between E. 21st St. and E. 24th St. has been Cleveland’s Chinatown. Among Chinatowns of American cities, Cleveland’s is very small. By 1980 2,000-2,500 Chinese were living there. In the 1980s there were 3 Chinese restaurants and 2 Chinese grocery stores on this block. Next to one of the restaurants, the Shanghai, stands the On Leong Assn. Bldg. On the 3rd floor is the On Leong Temple, which is used for (Buddhist) worship a few hours a week, but more often serves as a meeting hall. The Sam Wah Yick Kee Co., the larger of the grocery stores, in its heyday delivered merchandise to 50 Chinese restaurants in Greater Cleveland and about 30 more downstate and around Pittsburgh.

From its beginning, the Chinese community maintained many Chinese values and traditions. They celebrated festivals on the Chinese calendar, most prominently the Chinese New Year in February. The Chinese were attached to their country of origin. Early in 1911 Dr. Sun Yat-sen stopped at Cleveland on one of his worldwide tours and spoke at Old Stone Church. Meetings were held at the Golden Dragon Restaurant on Public Square to rally support and to raise funds for his revolutionary movement to overthrow the rulers of the Qing (Ching) Dynasty. On 11 Feb. 1912, 4 months after the founding of the Republic of China, a celebration was held at Old Stone Church and a telegram of congratulations was sent in the name of the Chinese residents of Ohio to Dr. Sun, president of the Chinese Republic. Twenty-six years later, the Chinese were again active in fundraising to support the war effort and civilian relief in the Sino-Japanese War. They rallied behind the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Assn., the Cleveland Chinese Student Club, and later the Chinese Relief Assn. About 500 Chinese residents pledged $3,000 a month. From 1937-43 $180,000 was donated for food, clothing, and medicine. In July 1938 the Cleveland Chinese Student Club published a quarterly, the Voice of China. Its editorials and articles strongly criticized the U.S. policy of selling scrap iron and oil to Japan; pointed out the weakness of the Neutrality Act; and urged the public to boycott Japanese silk. Three Caucasian Clevelanders served along with 4 Chinese on the editorial board. Sentiments toward the Chinese among segments of Americans had been changing, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed in 1943.

The Chinese population increased by about 100 between 1930-60. The 1960 census reported 905. After 1960 there was an influx of Chinese from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Some of the young Chinese who came to the U.S. in the late 1940s and early 1950s for university studies chose to stay permanently and were now establishing families in all parts of Cleveland and the suburbs. Beginning in the late 1970s, a small number of engineers and scientists from the People’s Republic of China came to Cleveland for graduate study, and these increased to over 100 at CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY after 1980. In 1990 the census estimated that 985 Chinese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong immigrants resided in Cleveland proper. The new residents came from central and northern China and diluted the Cantonese concentration of the earlier settlers. Together with the offspring of the Chinatown residents, mostly college-educated, they advanced into the professions of engineering, medicine, and the sciences. The faculties of BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE, Western Reserve Univ., Case Institute of Technology, and other colleges in Cleveland had increasing numbers of Chinese in their ranks. In the 1950s the active mainstream of the Chinese population in Cleveland was the membership of the Chinese Students’ Assn. of Cleveland. As the students completed their studies and advanced in their professions, they changed their organization in the 1960s to the Chinese Student & Professional Assn. of Cleveland, and in 1977 adopted the name Chinese Assn. of Greater Cleveland.

One institution in Cleveland that worked with the Chinese from the time of their early settlement was the Christian church, specifically Old Stone Church. For 50 years, starting from 1892, the church conducted a Sunday school for the Chinese, teaching them English and the Gospel. The church viewed its work as a mission comparable to that carried out by the missionaries it sent to China. Instrumental in this work were 2 members of the church, Marian M. and Mary F. Trapp, sisters and public-school teachers who worked for 30 years among the Chinese residents living near the church. The sisters obtained a working knowledge of Chinese (Cantonese) and assisted the Chinese in business problems and other matters. In Dec. 1941, with the support of the Cleveland Church Fed., Old Stone Church, and First Methodist Church, a Chinese Christian Ctr. was established in EUCLID AVE. BAPTIST CHURCH. Language classes, worship services, and youth activities were transferred from Old Stone Church to the center. Dr. Wm. Fung came to Cleveland to serve as director, and his wife, Shao-ying Fung, assisted in teaching classes. In 1948 Dr. Fung was succeeded by Rev. In Pan Wan, a Baptist minister. The center’s activities were continued until 1953, when Rev. Wan left. Language classes were conducted periodically at Euclid Ave. Baptist Church in the late 1950s, and Bible studies were held in homes.

In the early 1960s the Protestants among the Chinese were meeting in homes for prayers and Bible study. In 1965 their representatives appealed to Rev. Lewis Raymond, pastor of Old Stone Church, and obtained the free use of the church’s facilities. Sunday worship services in Chinese and Bible classes began at Old Stone on 12 June 1966 and the Cleveland Chinese Christian Fellowship was born. The Fellowship became the Cleveland Chinese Christian Church in 1975, having called Rev. Peter Wong to be its pastor. The average number of worshippers on Sundays rose to 110 by the end of the decade. In 1983 the church moved to its own sanctuary building at 474 Trebisky Rd. in RICHMOND HEIGHTS With membership grown to 200, the church added an annex housing classrooms and a gym in 1994. Outside of the Chinese Christian Church, Chinese Protestants worshipped at various denominational churches in Greater Cleveland. The number of Roman Catholics among the Chinese is estimated to be about 20-25% of that of Protestants.

With the growth of the Chinese community in the 1960s, the movement to preserve Chinese cultural values became strong. In 1966 the Chinese Academy was formed on the east side to give Chinese children instructions in the Chinese language and history on Saturday mornings. After using the facilities of two churches in CLEVELAND HEIGHTS, the academy settled at Noble Rd. Presbyterian Church in 1973. In 1980 Chinese residents in the west and south sides started the Academy of Chinese Culture, and since 1981 it had made use of rooms in schools and churches in STRONGSVILLE during weekends to conduct classes for children. Peter C. Wang, founder of the Chinese-American Cultural Assn. in 1961, offered tuition-free classes in Chinese in public libraries to those interested throughout the 1960s. In 1975 Laurence Chang wrote and produced 2 1-hour TV programs on “Values and Institutions of Chinese Culture,” which were broadcast over WVIZ (Channel 25). Through these activities Clevelanders gained broader views of China and Chinese culture. A symbol of the Chinese presence in Cleveland is the marble garden with a bronze statue of Confucius in the center, a gift to Cleveland from the City of Taipei, Taiwan, which was dedicated as part of the CULTURAL GARDENS in Wade Park on 21 Sept. 1985. The China Music Project, started in 1980, continued to bring to Cleveland musicians from Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong and present them in concerts of traditional Chinese music.

K. Laurence Chang

Case Western Reserve Univ.

Fugita, Stephen, et al. Asian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland (1977).

Last Modified: 11 Jul 1997 01:30:56 PM

Parma from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History