The pdf is here

The History of Term Limits in Ohio

By Michael F. Curtin

Ohio is one of 15 states to limit the number of terms its state lawmakers can serve. However, this is a relatively recent development. For most of its history, Ohio imposed no limit on the longevity of state legislators.

In the early 1990s, national conservative and libertarian organizations initiated ballot issues in more than 20 states to limit the terms of U.S. senators, U.S. representatives, state senators and state representatives.

The most prominent of these organizations is U.S. Term Limits of Fairfax, Va. (http://termlimits.org)

The high-water mark of this movement was 1992. On Nov. 3, 1992, voters in Ohio and 14 other states decided term-limit issues.

In Ohio, by overwhelming ratios, voters approved all three term-limit issues on the ballot:

- State Issue 2, approved by 66 percent of the voters, limited U.S. senators from Ohio to two successive terms of six years, and limited U.S. representatives from Ohio to four successive terms of two years.

- State Issue 3, approved by 68 percent of the voters, limited state senators to two successive terms of four years, and state representatives to four successive terms of two years.

- State Issue 4, approved by 69 percent of the voters, limited the lieutenant governor, secretary of state, treasurer of state, attorney general and auditor to two successive terms of four years.

At the time, most Republican and conservative organizations nationally and in Ohio supported the term-limit issues. Most Democratic and liberal organizations either opposed the issues or remained neutral, recognizing the overwhelming support the issues had in public-opinion polls leading up to the election.

However, the voter-approved limits on U.S. senators and U.S. representatives never took effect.

Term-limit opponents filed lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of states setting limits on the tenure of federal officeholders.

On May 22, 1995, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton, by a 5-to-4 decision, ruled that states cannot impose qualifications for prospective members of Congress that are stricter than the qualifications specified in the U.S. Constitution.

With that decision, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated congressional term limits in 23 states.

Left standing, however, were voter-approved term limits applicable to state executive officeholders and state lawmakers.

Ohio’s new term limits restricted all statewide officeholders and state legislators to no more than eight consecutive years in office.

Because the state constitutional amendments were approved in November 1992, to take effect in January 1993, and because laws cannot be made retroactive, that meant any Ohio statewide official or legislator in office as of January 1993 could not serve beyond Dec. 31, 2000.

Prior to adoption of these amendments, the only Ohio statewide office with a term limit was the office of governor.

On Nov. 2, 1954, Ohio voters (55 percent to 45 percent) approved a state constitutional amendment to establish four-year terms for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general and secretary of state, and to limit the governor to two successive terms.

The Ohio Supreme Court later interpreted the amendment to allow a former governor to run again for governor after being out of office for four years.

Similarly, the amendments approved in 1992 allow officeholders to run again for the same office, as long as they have been out of office for at least four years.

The debate over term limits is as old as the republic, although the popularity of term limits is largely a modern-day phenomenon.

In 1781, the Articles of Confederation limited delegates to the Continental Congress to three years of service in a six-year period. This thinking, which traces back to ancient Greece, is rooted in the philosophy that those who govern should be reminded that they soon will return to the ranks of the governed.

However, the framers of the U.S. Constitution considered and rejected term limits for members of Congress. This thinking is rooted in the philosophy that frequent elections give the people sufficient opportunity to oust officeholders.

The Founding Fathers also imposed no limit on presidential terms, although for many decades it was customary for presidents to serve for only two terms.

Following the fourth consecutive presidential victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944, Congress moved to establish a two-term limit for presidents.

On March 21, 1947, Congress passed an amendment, to submit to the states for ratification, declaring, “No person shall be elected to the office of President more than twice . . .” The ratification process was completed on Feb. 27, 1951.

The modern-day popularity of term limits correlates strongly with voter disgust over official misbehavior, scandals, legislative gridlock, and highly-negative, highly-partisan campaigning and governing.

Indeed, there is little sign that voters in Ohio are having second thoughts over the value of term limits. In April 2005,

the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics, at the University of Akron (www.uakron.edu/bliss) , concluded a two-year study titled “Assessing Legislative Term Limits in Ohio.”

The study concluded that approximatey two-thirds of Ohioans believe that term limits have fostered good government and improved the state.

“On balance, the (poll) respondents felt that term limits brought fresh ideas into the legislature, increased the number of ‘citizen legislators,’ and had not reduced the effectiveness of the legislature, increased the responsiveness of the legislature to the public, and did not reduce the wisdom and experience of the legislature.”

Interestingly, the study also found that those closest to state government – officeholders, lobbyists and those who study the workings of state government – are strongly critical of term limits.

About three-fourths of the close observers of state government would favor the repeal of term limits, the study found.

These close observers believe that term limits have weakened the legislative branch and increased the power of special interests, which are believed to have more expertise than relatively inexperienced legislators.

Critics of term limits believe that state government is a complex business with many complex issues, and that it takes years for lawmakers to develop the necessary expertise to effectively evaluate policy alternatives.

The close observers, according to the Bliss study, “report that (legislative) committee members are less knowledgeable about the issues, less willing to compromise, and less courteous to fellow committee members.”

There is no question that term limits guarantee an inexperienced legislature. When the 124th Ohio General Assembly convened in January 2001, nearly half of the previous legislature – with 211 years of combined experience – were gone.

Prior to 2001, Ohio was among the states with the most experienced legislatures. Today it ranks among the states with the least experienced legislatures and the highest turnover rate of lawmakers.

According to the Bliss study, “When the Ohio General Assembly convened in January 2003, none of the 99 representatives or 33 senators had held his or her seat for more than six years. In the 1990s, the average length of service was 21.6 years.”

With such a wide gap between the views of the general public and those of close observers of the Ohio legislature, some analysts have begun to explore the possibility of asking the electorate to extend term limits to 12 years, from the current eight, rather than asking voters to eliminate term limits altogether.

The Bliss study found that about one-third of Ohioans who support term limits say they would consider extending them to 12 years.

The forum in which that proposal is likely to get serious study is the recently-formed Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission. (www.ocmc.ohio.gov)

The 32-member commission, created in 2012 by the state legislature, is charged with analyzing proposed changes to the Ohio Constitution and making recommendations to the General Assembly.

The commission, composed of 12 state legislators and 20 persons appointed by those 12, can forward a recommendation for constitutional change to the General Assembly only if the the proposal obtains a two-thirds favorable vote.

Like any proposed amendment to the Ohio Constitution, a proposal cannot go on the statewide ballot unless it receives a three-fifths favorable vote in both the Ohio Senate and the Ohio House of Representatives.

Regardless of one’s personal opinion on term limits, it is clear that the issue will continue to receive considerable scrutiny in the near future, and the General Assembly will debate whether and when to ask voters to change the current eight-year limit.

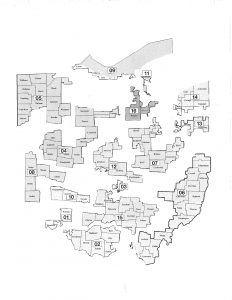

Columbus native Michael F. Curtin is currently a representative (first elected 2012) from the 17th Ohio House District (west and south sides of Columbus). He had a 38-year journalism career with the Columbus Dispatch, most devoted to coverage of local and state government and politics.

Mr. Curtin is author of The Ohio Politics Almanac, first and second editions (KSU Press).

Finally, he is a licensed umpire, Ohio High School Athletic Association (baseball and fastpitch softball)