Florence Allen, Elizabeth J. Hauser and Greta Coleman 1914 wiki

Florence Allen, Elizabeth J. Hauser and Greta Coleman 1914 wiki

Elizabeth J. Hauser: The Woman Who Wrote

Tom L. Johnson’s Autobiography

by Marian J. Morton

The pdf is here

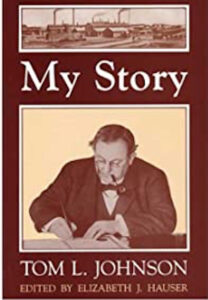

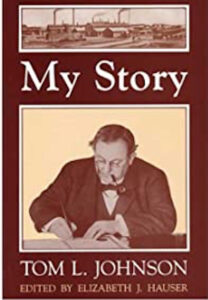

The book is called My Story. Its cover shows Tom L. Johnson, Cleveland’s most famous, most beloved mayor, writing something – presumably this book, his autobiography. But it’s a good bet that he didn’t write much of it. The woman who did – and who helped to create this enduring self-portrait of Johnson – was Elizabeth J. Hauser. If he is Cleveland’s most famous, most beloved mayor, she should get some of the credit. This is her story. Or part of it.

VOTES FOR WOMEN

Hauser became a suffragist at age 16 when she joined the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association (OWSA). She was born in 1873 in Girard, Ohio. Her parents, David and Mary Bixler Hauser, were German immigrants. [1] Her father was a butcher.

After high school, Hauser began her career as a journalist at local newspapers, including the Warren Tribune Chronicle. She also worked closely with OWSA president, Harriet Upton Taylor, in the association’s headquarters in Warren, Ohio. In 1895, Hauser became press secretary for both the OWSA and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[2] She considered herself a writer and journalist all her life.

When the NAWSA moved its headquarters to Warren in 1903, Hauser ran the office. She had already become a force in the Ohio suffrage movement. The Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1899 described her as “probably the youngest active worker in the cause for equal rights.”[3] The newspaper also carried her call to the seventeenth annual convention of the OWSA in Cleveland in 1902: she declared, “Ohio, a great progressive commonwealth, … still holds its intelligent women, politically, in the same class as minors, lunatics and criminals.” [4]

Hauser had certainly met Johnson before she arrived in Cleveland in fall 1910. He had been converted to the cause of woman suffrage by Marie Jenney Howe, at least according to her husband Frederick C. Howe, a close friend and political ally of Johnson. [5] Johnson and Hauser both spoke at the annual convention of the OWSA in Youngstown in October 1907: “Friends and enemies alike [were] invited to attend.”[6] In 1909, after the NAWSA and Hauser moved to New York City, Johnson visited its new headquarters.

While she was working in New York, Hauser met Joseph Fels, a wealthy soap-manufacturer (Fels Naptha), who, like Johnson, had become a single taxer. Fels established a foundation to further the single tax cause, and in August 1909, he hired Hauser to work for the foundation for $2,000 a year. [7] Fels, a close friend and supporter of Johnson, probably paid her to edit My Story.

Hauser’s primary assignment when she came to Cleveland was to organize Cleveland suffragists into the Cuyahoga County Woman’s Suffrage Party. She brought “new life and hope” to the Cleveland movement, [8] quickly opening an office and calling a meeting of interested women. She also found time to help out her friend Johnson, who needed a sympathetic editor for his autobiography.

EDITING MY STORY

When Johnson served as mayor of Cleveland, 1901-1909, he joined the ranks of nationally known mayors, including Hazen Pingree of Detroit and Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones and Brand Whitlock of Toledo, who represented Progressive reform at the local level. In this context, Johnson embarked on My Story to explain how an extraordinarily successful man like himself could have been defeated by the very Cleveland voters who had made him mayor in three earlier elections. His answer: I have been beaten by “Privilege.”

During the last five months of his life, in failing health, he dictated most of the book’s contents to Hauser. She transcribed the material and organized into coherent chapters the words of a man skilled at public debate but not at writing narrative. [9] For this, he generously gave her credit in the book, and she is acknowledged also on the book’s cover. But she did far more. As she listened, wrote down, organized, and edited his words, she realized that Johnson was not telling the story of himself, or at least, not the story that Clevelanders and his fellow Progressive reformers wanted to read. Her job was to tell that story.

Johnson describes in the first chapter of My Story his youth in Kentucky – his father “a slave owner and cotton planter” [10] and reluctant supporter of the Confederacy, was left penniless by the Civil War. Johnson at age eleven went to work selling newspapers on the train, where he learned that creating a monopoly – in this case of newspapers – was the easiest way to get rich. His parents continued to move around as his father tried to figure out how to earn a living. During this time, Johnson received his “one and only full year of schooling.”[11] From there, he rose rapidly from inventing a streetcar farebox to owning streetcar lines in several cities in his early thirties and then to a mansion on Euclid Avenue. This rags to riches story is the stuff of much American autobiography. Johnson probably included it only because Hauser urged him to: “It was with extreme difficulty that he was induced to include the few delightful personal anecdotes which lend such charm to the early chapters,” she confesses. [12] And indeed, Johnson’s own introduction to the book describes not himself, but “Privilege” – “Big Business, corrupt bosses, subservient courts, pliant legislatures and an Interest-controlled press,” [13] with which he did battle and which not only defeated him but turned the book into a political treatise, instead of a story about its author.

My Story does paint lively portraits of some of Johnson’s personal heroes and political collleagues. First among them, of course, was Henry George, whose book, Social Problems, converted Johnson to the single tax that would become his primary weapon in his fight against Privilege. His conversion from businessman to reformer – although not immediate – became a turning point in his life. Johnson also admired George’s courage – his “willingness to ‘raise hell’ for the sake of a cause or to give one’s life for it.” [14] Another hero: Harrison Cooley, pastor of the Disciples of Christ congregation of which Johnson was a member, who reformed the city’s public facilities for the indigent, ill, and aged, which were named Cooley Farm in his honor. And a brilliant young lawyer, Newton D. Baker, who became Johnson’s city solicitor and later mayor and still later Secretary of War under President Woodrow Wilson. And also Peter Witt, who came to heckle Johnson and stayed to join his ranks. He became Johnson’s city clerk in 1903 and remained in Cleveland politics for decades. Witt sometimes ran interference for Johnson. At one Cleveland City Council meetings, Witt – brushing aside the reasoned arguments of lawyer Baker – went after the directors of the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company for insulting Johnson and members of council: “Witt not only denounced the policy and methods of the railway company, charging that in the past it had bribed councilmen, corrupted legislators, used dishonest judges …. But one by one he called the men present by name and shaking his finger at them declared the responsibility of each for the particular things of which he held that man to be guilty.” [15]

Johnson describes a few of his own dramatic moments. In 1897, when he was the political manager for George’s campaign for mayor of New York, he was hissed at a public meeting in Brooklyn. He challenged “the group of hissers …. “’Well, what is it? What don’t you like…. ‘Well come on, give us some more of it. I like it, it makes me feel good’ … But I got no response,” and the men slunk away.[16] It became Johnson’s habit to publicly challenge his opponents to a debate; few men took him up on it. As mayor, he urged a councilman to pretend to take a two thousand dollar bribe so that the briber might be revealed at the next council meeting. As the councilman publicly threw the bribe on the table, the briber was arrested as he ran for the door. [17]

These were skirmishes in his long battle against Privilege, the theme of his story. “The city government belonged to the business interests generally …. The campaign funds came largely from business men who believed in a ‘business man’s government ,’ and who couldn’t or wouldn’t see that there was anything radically wrong with it.” [18] In 1907, Johnson ran for re-election against Senator Theodore Burton. Here is Johnson’s version: “Privilege was fighting with its back to the wall now and stopped at nothing in the way of abuse or persecution, not of me only but of the men associated with me. At their clubs, our boys were treated with … obvious insult…. Everywhere the campaign was the town talk. In banks and factories, in offices and stores, on the [street]cars, in the home, in the schools … Even little children in the public schools engaged in the controversy.” [19] If there is a villain in the story, it is Mark Hanna, Johnson’s long-time political and business rival. Hanna, the Republican kingmaker, denounced Johnson as a “the national leader of the Socialist party …. A vote for Johnson is a vote for chaos in this country …. Socialists like thieves steal up behind to stab.” Johnson describes Hanna as “the representative and defender of Privilege.” [20]

But Johnson writes more about his political philosophy than about political drama. Chapters are devoted to teaching “the Lessons [the 1889 flood at] Johnstown Taught” (the flood was caused by “Special Privilege”) ; “The Lessons of Monopoly” ( “law-made privilege” creates poverty, which in turn creates crime, corruption, and vice); “More Lessons of Monopoly” (the necessary corruption of private ownership of streetcars persuaded Johnson to get out of the streetcar business); “The Way Out” (Privilege blocks just taxation). Many more pages teach about his other political platform than describe his actions: the single tax, municipally owned utilities, and municipal home rule. These “lessons” overwhelm not only the narrative, but Johnson, the narrator and the supposed topic of the book.

Only in formal portraits and in some of the fine photos by Louis Van Oeyen does Johnson appear front and center: addressing a tent meeting; surveying the line for the three-cent fare streetcar; driving the first 3-cent fare streetcar; receiving victorious election returns; chatting with a young citizen; entering the voting booth; signing bonds (this is the portrait that appears on the front of the autobiography).

Johnson ends the book optimistically: “The defeats of the movement loom large …. But it is a forward movement and this is the word of cheer I would send to those taking part in it. It is in the nature of Truth never to fail.” [21] Days later, he died. And to his contemporaries, the defeats still loomed large.

Hauser then had to edit an autobiography that was not – in its original form – very much about its subject; she had to focus on Johnson, and not on the defeated Johnson but on the victorious one. It was an enormous challenge. She transcribed his materials as he lay dying, and she had to complete the book in the days shortly after his death so that it could be re-published as soon as possible in the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Her editing, and especially her Foreword and her concluding chapter, she explains, are intended to “capture the human quality in him.” Johnson was a reluctant autobiographer, focused on the present, not his own past; he bowed to public pressure to write about himself only “after he became so ill that the slightest physical or mental effort was a severe strain.” [22]

Hauser makes no pretense of journalistic objectivity. Johnson was a “Big, brave, dauntless, resourceful soul.” [23] So self-effacing that only at her urging, did he include the details of his early life. So modest that he understated “the overwhelming odds against which he fought and conquered” and the “persecutions and cruelties of the street railway company and the business interests allied with it” that included the Chamber of Commerce, the retailers, the lawyers, doctors, and ministers. [24] He had great moral courage, championing causes before they became popular: municipal home rule, just taxation, initiative, referendum, and recall. And “After he became convinced of the justice of woman suffrage, he made several speeches for it.” [25] (Johnson apparently did not mention woman suffrage in the dictated materials, and Hauser did not add it.) Hauser lists the accomplishment he had omitted: an efficient city government, a building code, a forestry department, street-paving, bath-houses, parks and recreation facilities, all achieved without graft or scandal. [26] She repeats Lincoln Steffens “estimate of Mr. Johnson as ‘best mayor’ and of Cleveland as ‘the best governed city in the United States.’” [27]

Johnson also did not mention his wife, daughter, and son. Nor did Hauser.

Autobiographers don’t get to write about their own deaths, but Hauser finishes My Story for him. Hauser’s concluding chapter, “Blessed the Land That Knoweth Its Prophets Before They Die,” likens Johnson to the towering Biblical figures who spoke truth but were too often ignored. Hauser describes Johnson’s last painful months, his last public speeches to cheering audiences, his brave death on April 10, 1911, the weeping crowds who watched his passing hearse. She quotes the Cleveland Leader: “’The heart of the city stopped for two hours while the simple cortege passed through the lines of silent, grief-stricken men and women.’”[28]

Hauser had written Johnson’s eulogy. She started out to humanize him; instead she had turned him into a saint.

Newspaper headlines informed readers about Johnson’s last days: “ JOHNSON’S DEATH MATTER OF HOURS”; “TIRED OUT, JOHNSON AWAITS HIS DEATH.”[29] Barely two months after his death, the Cleveland Plain Dealer announced that it would serialize the book: “Tom L. Johnson’s own story – written by himself.” [30] Well, not exactly.

But My Story – and Hauser’s version of this heroic reformer pitted against the powerful status quo – became “the single most important surviving primary source concerning Tom L. Johnson’s role in the American reform movement and Cleveland’s reaction to his mayoral administration.”[31] She had begun his canonization. Historians, sculptors, painters, journalists, and students would follow her lead. [32]

KEEPING THE FAITH

As the book was being prepared for publication, Hauser threw herself back into her suffrage work. In June 1911, she organized a rally at Cedar Point, where she shared the speakers’ platform with her old boss, Harriet Taylor Upton, and Johnson’s colleague, Newton D. Baker. She enlisted the support of some of Cleveland’s “fashionable” women from its “first families. [33] In the 1911 Cleveland mayoral race – run without Johnson for the first time in a decade -, Hauser publicly challenged the six candidates to answer this question: “’Are you in favor of the political enfranchisement of the women of Cleveland and of Ohio?’” All but one answered in the affirmative.[34]

Anti-suffragists, however, remained opposed. In an effort to win them over, the suffragists interviewed by the Cleveland Plain Dealer in April 1912 assured its readers that women would not lose their femininity if they voted: “Why Bless Your Hearts, We’ll Be Just the Same,” read the headline. “Even the leader of the movement in Cleveland, Elizabeth Hauser, to whom has been accorded the credit of securing for the suffrage cause the official public recognition it has received, is of the womanly feminine type.” [35]

The suffragists’ immediate goal was to reform the Ohio constitution by putting on the ballot in 1912 an amendment that would have enfranchised women by changing the words that described a voter from a “white male” to “every citizen.” When enough signatures had been collected, Hauser traveled to Columbus to present the petitions to the state legislature. She opened a headquarters for the Ohio suffrage movement there and registered as its lobbyist. On the eve of the election, Hauser invoked the suffragist heroine Sojourner Truth’s dramatic testimony in Akron in 1851: “If the first woman God ever made [Eve] was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again. And now dey is asking to do it, de men better let them.’” [36] Truth’s speech won great applause. But the suffrage amendment lost by 87,000 votes. In August, Hauser had predicted the suffragists’ response to possible defeat: “The forces of evil may prevail to the extent of defeating amendment 23 …, but the righteousness of the measure is not thereby defeated. Its operation is only deferred.”[37]

So Ohio suffragists tried again in 1914, this time using the referendum to amend the Ohio constitution. Hauser continued as a field organizer for the OWSA, acting as its press agent and lobbyist, and then its chairman. She spoke often and forcefully. She told her audience in Salem, Ohio, “All just government is by the consent of the governed, and you cannot deny to woman the right to vote without repudiating the Declaration of Independence.” Targeting the anti-suffragists, she argued, “There is no reason why a few sheltered, protected women, who realize nothing of the sufferings and wrongs and abuses of others of their sex, should be used as an excuse for defeating the cherished purpose of those who are awake, who would make of this a better land in which to live.”[38] A month later she went after the “liquor forces” who opposed votes for women: “The liquor interests of Ohio are out to defeat woman suffrage…. [W]e believe the time has come when we must drive our most bitter enemy from seclusion and force a fight in the open.”[39]

Another defeat in 1914 inspired suffragists to pursue a narrower goal: a state bill that would allow women to vote only in presidential elections. On its behalf, Hauser invoked Johnson: “if Tom Johnson were here, he’d be with us in this fight.” [40]This bill passed the legislature but was repealed by a referendum although the suffragists’ leading lawyer Florence Allen challenged its legality.

Ohio women – and all American women – did get the vote on August 18, 1920 after Congress and three-fourths of the states had passed the Nineteenth Amendment.

Months before, the NAWSA, led by Carrie Chapman Catt, anticipating this victory and its challenges, formally established the League of Women Voters (LWV) in February 1920. In May, Hauser returned to Cleveland to help re-organize the Cleveland Woman Suffrage Party of Greater Cleveland into the new Cleveland LWV. Suffragist leader Belle Sherwin was elected president of the local group; Hauser became a regional director. Both would soon assume leadership positions in the national LWV. Sherwin was its president, 1924-1934. Hauser served on the national board and executive council through the 1930s. In 1931, Hauser, Sherwin, Upton, and Allen, Hauser’s long-time friends and allies, were named to the national LWV Roll of Honor for their role in winning the vote.

Although the league had a broad-ranging reform agenda including minimum wage and protective legislation for women and more stringent child labor laws, its primary goal was to educate newly enfranchised women to vote and run for office to ensure that the long suffrage battle had not fought in vain. The league also championed other political reforms that Johnson might have found congenial, such as the city manager form of government, initially supported, then opposed by Baker, and proportional representational voting, supported by Witt. [41]

The LWV was non-partisan, endorsing issues, not candidates. This was a pragmatic decision since members and officers belonged to different political parties. For example, Upton was a Republican; Allen, a Democrat.

Hauser joined the Progressive Party as did Witt and Howe. She returned to Cleveland in July 1924 for the party convention, which nominated Senator Robert LaFollette for President. Identified as the president of the Ohio LWV, she was photographed with other “Progressive Bosses,” including labor leaders, trade unionists, Socialist Morris Hillquit, and Harriet Stanton Blatch, suffragist and daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. [42] LaFollette had supported woman suffrage early in his political career. The party platform endorsed familiar reform issues such as the public ownership of railways and water sources and just taxation. Hauser and Witt served on the party’s Ohio Conference for Political Action. Her connections to women voters made her valuable to Lafollette; he added political breadth to the league.

Hauser served simultaneously the League of Women Voters and the Progressive Party, seeing both as logical expressions of her hope to reform American life. Just weeks before the 1924 party convention in Cleveland, she addressed a league meeting in Buffalo on “Political Housekeeping.” “It will be a great day for this country when the women voters, conscious of their might, undertake a political clean-up with the same vigor which characterizes their housecleaning…. Dare we suggest that it may even be necessary … to get a new house if the old one cannot be made healthfully habitable.[43]” Johnson and LaFollette would have agreed about the need for a new house.

MY STORY, OUR STORY, HER STORY

Thanks to Hauser, My Story became our story. As Hauser well knew, the book was what Johnson’s devoted contemporaries wanted to read. Her version of Johnson’s story also shaped all later conversations about Johnson and inspired historians, teachers, journalists, painters, poets, film-makers, and two fine statues, one in our Public Square. The story set the bar so high for later mayors that no one – except maybe Baker – has come even close to measuring up although Dennis Kucinich deliberately cast himself as Johnson’s heir. Cleveland history buffs still like to read My Story. We love Tom Johnson, the champion of Progressive reform, “the best mayor” of our “best governed city.” And we read Hauser’s words about our “big, brave, dauntless, resourceful” leader and sigh wistfully, contrasting Cleveland’s golden years under Johnson with its decline under all the lesser mayors who followed.

Hauser’s own story, on the other hand, remains pretty much untold although she is less anonymous than the tens of thousands of her fellow suffragists. No statues, no paintings, no books celebrate her. But her name does appear on the bronze League of Women Voters National Roll of Honor. And she did become a professional writer, an applauded speaker, a seasoned organizer, an activist who hobnobbed with the important women and men of her day. Not bad for the daughter of a butcher, from a tiny Ohio town, who had only a high school education. She never became mayor of a major American city. But she helped to create one for us.

[1] https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1009638274

[2] https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1009638274

[3] Cleveland Plain Dealer (CPD), October 1, 1899: 24.

[4] CPD, September 7, 1902: 6.

[5] Frederic C. Howe, Confessions of a Reformer (Kent, OH, 1988), 137.

[6] CPD, October 6, 1907: 46.

Morning News, August 7, 1909: 6.

[8] Virginia Clark Abbott, The History of Woman Suffrage and the League of Women Voters in Cuyahoga County, 1911-1945 (Cleveland, 1949), 12, 15. This is the best source on the local movement in this period. See also http://teachingcleveland.org/how-cleveland-women-got-the-vote-by-marian-morton/

[9] Tom L. Johnson, My Story (My Story), edited by Elizabeth J. Hauser, second edition IKent, OHio, 1993), xxvii-xxix.

[10] My Story, 2.

[11] My Story, 7.

[12] My Story, xxviii.

[13] My Story, vi.

[14] My Story, 58.

[15] My Story, 258.

[16] My Story, 56.

[17] My Story, 214-215.

[18] My Story, 114.

[19] My Story, 270.

[20] My Story, 202-203.

[21] My Story, 294.

[22] My Story, xxviii.

[23] My Story, xxxviii.

[24] My Story, xxxviii.

[25] My Story, xxxii.

[26] My Story, xxxv.

[27] My Story, xxxvi.

[28] My Story, 313.

[29] CPD, April 8, 1911: 1; CPD, April 9: 1.

[30] CPD, June 15, 1911:12.

[31] John G. Grabowski, Forward to Second Edition, My Story, xxiii.

[32] Johnson has never lacked for hagiographers. Here are only a few.

“America’s Best Mayor,” (2012) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v39bCf509BQ;

Robert H Bremner, “Tom L. Johnson,” Ohio Historical Journal. Volume 59, January 1950, 1-13.

George Condon, Cleveland: The Best Kept Secret (Cleveland, 1981).

Edmund Vance Cooke, “A Man Is Passing” (1910).

Brent Larkin, Plain Dealer, August 4, 2019: E 1.

Carl Lorenz, Tom L. Johnson (New York, 1911).

Eugene E. Murdock, “Cleveland’s Johnson: Elected Mayor.” Ohio Historical Journal, Volume 62, October 1953, 323-333.

“Progressive Reform for the Common Man,” (2009)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XW8sJS6UPPw.

Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism in Ohio 1897-1917 (Columbus: 1964.

See also these: http://teachingcleveland.org/tom-l-johnson-aggegation/

Grabowski’s Foreword to the second edition of My Story makes a more cautious assessment xi-xxv.

[33] Abbot, 12-17.

[34] CPD, August 19, 1911: 3.

[35] CPD, April 7, 1912: 8.

[36] Topeka Plain Dealer, Sept. 6, 1912: 2.

[37] CPD, August 31, 1912: 9.

[38] Salem News, June 11, 1914: 8.

[39] Akron Beacon Journal, July 13, 1914: 2.

[40] CPD, December 10, 1016: 15.

[41] Abbott, 16, 18.

[42] Casper Star Tribune, July 5, 1924: 1.

[43] Zanesville Times Signal, July 13, 1924: 15.

Marian J. Morton is professor emeritus of history at John Carroll University and the author of many articles and books on Cleveland history, including three other Arcadia titles: Cleveland Heights, Cleveland’s Lake View Cemetery, and Cleveland Heights: The Making of an Urban Suburb. She has written many essays for Teaching Cleveland Digital and for that we will be eternally grateful.