| 1 | Frances Bolton from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland |

| 2 | Frances Payne Bolton Biography |

| 3 | The Life of Frances Payne Bolton |

www.teachingcleveland.org

1 Ernest Bohn from Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

2 Public Housing in Cleveland: A History of Firsts

3 Time and Again from Cleveland Magazine July 2009

4 Robert A. Taft and Public Housing

5 Bohn’s Palisades from “The Cuyahoga” by William Donohue Ellis

6 History of Public Housing in Cleveland from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

1 Federal Arts Project from Cleveland Historical

2 Work Projects Administration (WPA) from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

3 Federal Art In Cleveland 1933-43

4 The Cleveland Public Library and the WPA: A Study in Creative Partnership

5 The Works Progress Administration leaves a legacy in Northeast Ohio WKSU Mark Urycki 9/15/2011

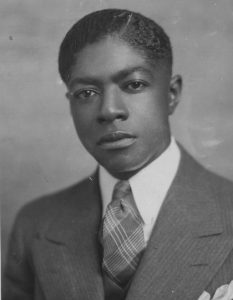

John O Holly 1935 (Cleve Public Library)

1 Cleveland’s Original Black Leader: John O. Holly By Mansfield Frazier

2 Carl Stokes on John O. Holly from “Promises of Power”

3 Future Outlook League from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

4 John O. Holly from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

5 Merchants of Tomorrow: The Other Side of the “Don’t Spend Your Money Where You Can’t Work” Movement

Plain Dealer article written by Bob Rich and published on July 16, 1996

Cleveland’s own G-Man, Eliot Ness, came to town in the summer of 1934 as head of the Treasury Department’s Alcohol Tax Unit. He had achieved celebrity as the chief of a special Justice Department task force that had literally battered down the doors of Al Capone’s breweries and warehouses in Chicago during Prohibition, but it would be many years later, long after Ness was dead, before a book and TV would make him into a near-mythical lawman.

Ness had always given credit for jailing Capone to the undercover work of the IRS, but he was symbolic of the new breed of enforcement officer: college-educated, smart, and incorruptible – “untouchable” as he became known for spurning constant bribe offers from Capone.

Cleveland had a new mayor, Harold Burton, who, when he couldn’t get the Republican Party’s endorsement, ran as an independent Republican and won. Burton appointed the 32-year-old Ness as his safety director in charge of a thoroughly demoralized force of 2,400 policemen and firemen.

Times had changed since Cleveland’s men in blue were the recognized model for the country under Mayor Tom Johnson; now, with the worst depression in history in full bloom, there were hundreds of homeless people, panhandlers, prostitutes and robbers; gambling was wide open, labor extortion common, the police rackets at full blast. Cops looked and acted the way they felt – slovenly and unkempt; sometimes they were informants and even enforcers for mob figures.

In December 1935, author Steven Nickel quoted Ness as telling the Cleveland Advertising Club, “In any city where corrpution continues, it follows that some officers are playing ball with the underworld. If town officials are committed to a program of `protection,’ police work becomes exceedingly difficult, and the officer on the beat, being discouraged from his duty, decides it is best to see as little crime as possible.’

Ness went on to explain that while he personally wasn’t against gambling, profits from illegal gambling opened the door to drug dealing, prostitution and union racketeering.

Quite a mouthful for a young man whom many locals considered not tough enough to be a top cop, with his college-boy good looks, university education and low-key manner. They began to believe him when he transferred 122 policemen, including a captain and 27 lieutenants, and replaced the head of the detective bureau.

Ness captured Cleveland’s affection when he made a flamboyant and courageous raid on the Harvard Club in Newburg Heights, a notorious gambling club operating openly with police protection, one month after his appointment as safety director. He had been called in by the county prosecutor even though the club was out of the city limits, and moved against it as a private citizen, accompanied by police and his newspaper reporter friends.

Now, with the city solidly behind him, Ness put together a team of volunteer detectives and police – Cleveland’s own group of “Untouchables” – and went after corruption in the police force. He used wiretaps, informers, subpoenaed bank accounts; the same tools of the trade he had used against Al Capone in Chicago. Grand jury indictments, trials and convictions followed.

Later, juries would send labor extortionists to jail, leading to anti-union charges against Ness. The AFL investigated and decided that Ness was only against labor racketeering.

He instituted a professional training program for police and reformed the traffic division leading to Cleveland being rated the safest city in the United States by the National Safety Council.

Many evenings, on his own time, he met with youth gang leaders and social workers. He fought to get city funding of playgrounds and basketball courts for Cleveland’s youth: “Keep them off the streets and keep them busy. It’s much better to spend a lot of time and money … keeping them straight than it is to spend even more time and money catching them in the wrong and then trying to set them straight.”

As a result of his programs, there was an 80 percent drop in juvenile delinquency.

Then, a much greater evil than corruption or organized crime struck: a serial killer – the man the media would call the Cleveland Butcher – who left pieces of corpses scattered about.

Wonderful first chapter of “Invisible Giants: the empires of Cleveland’s Van Sweringen brothers” By Herbert H. Harwood. This is on Google books and has limited access. But the first chapter alone is a terrific overview of the Vans, their family and first ventures in real estate.

Written by Carol Poh Miller

Myth, Modernity, and Mass Housing: The Development of Public Housing in Depression-Era Cleveland by Jennifer Donnelly

(from SAA meeting site: https://saa2015cle.wordpress.com/2015/08/04/the-story-of-steel-and-iron-in-cleveland/)

Contributed by John J. Grabowski, Ph.D.

If you are familiar with professional football (and one assumes many SAA members are) you know (should know!) that one of the most famous rivalries in the sport is that between the Cleveland Browns and the Pittsburgh Steelers. It’s a bit like Ohio State and the other university up north (family connections prevent me from using its name!). But the comparison ends there, because unlike college football with its origins in the Ivy League, that of pro football is connected to the steel mills and factories of the industrial Midwest. The Cleveland-Pittsburgh rivalry has at its roots, a blue collar aura and a link to a longer economic rivalry between two great American steel cities. And, that brings us to the story of steel and iron in Cleveland.

Even in this second decade of the twenty-first century, Clevelanders cannot divorce themselves from steel despite the city’s move into a post-industrial economy. Look closely at the city while you are here. The iron ore carrier, William G. Mather is anchored in the lake just beyond the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Take a tour of the Flats, and you’ll see ore freighters winding their way up the Cuyahoga to the ArcelorMittal mill. Now largely automated, it is one of the most efficient steel mills in the nation. If you take the time to go to the observation deck of the Terminal Tower, you’ll see its buildings and smokestacks to the south.

This modernized plant is the descendant of an industry that formed the economic backbone of the city from the period just after the Civil War to the 1960s. While early Cleveland blacksmiths worked iron, it was not until 1857 that the industry really got rolling, so to speak. Two Welsh brothers, David and John Jones, started the Cleveland Rolling Mills southeast of the city in the area now known as Slavic Village. By the 1880s, the making of iron and steel (the rolling mills had the first Bessemer converter west of the Appalachians) had displaced oil and refining as the chief industrial activity in Cleveland. As the mills grew, the process also became de-skilled and thus opened up jobs to thousands of immigrant and migrant workers. It’s not serendipity that placed some of the city’s ethnic neighborhoods near the mills; it was the need of workers to walk to their jobs. And chain migration brought sons, families, and relatives from what are now Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Ukraine, and other central and eastern European nations to mill neighborhoods like Tremont, Warszawa (now part of Slavic Village), and Praha. By the early twentieth century, the Europeans were joined at the mills by African Americans who saw Cleveland and jobs at the mills as a passage out of Jim Crow and into some degree of prosperity. That expectation was, unfortunately, not truly fulfilled, despite the fact that some migrants already had their roots in the industry in Alabama.

The making of steel then provided the basis for factories that turned it into a number of products — nuts, bolts, automobiles, sewing machines, roller skates, and even jail cells! The transport of iron ore itself provided the city with a host of sub-industries. Shipbuilding was one, with American Ship Building as a prime example. (It’s hard for some Clevelanders to admit this given that George Steinbrenner’s fortune came from the company and helped him bankroll the hated New York Yankees.) Originally ships were unloaded by hand. Up a plank with a wheelbarrow, down into the hold, shovel it full, take it out, dump it, and do it again. That ended with the invention of the Brown Hoist system (invented and built in Cleveland) and then the Hulett, invented by a Clevelander. Both systems eventually found use all around the Great Lakes and their manufacture brought wealth and fame to the city, along with labor strife. A strike at the Brown Hoist factory was, along with strikes at the Rolling Mills, a signifier that laboring conditions and pay in the city during its Gilded Age heyday (and afterwards) were matters of serious concern and contention. All this reminds me of a Depression-era “poem” my father taught me:

“Yesterday I met a man I never met before. He asked me if I wanted a job shoveling iron ore. I asked him what the wages were, ‘A dollar and a half a ton.’ I told him he could shoot himself, I’d rather be a bum.”

I suspect that this little snippet is a reminder that I, like many Clevelanders, have some steel in my family history. And, indeed, as noted earlier, it’s hard to let that history be forgotten. While the mills may not be what they used to be (thank goodness perhaps, because the pollution they created was extensive), it is still possible to see the history of steel in the city. The Brown Hoist Factory still stands on Hamilton Avenue; the site of the Cleveland Rolling Mills (which later became part of United States Steels American Steel and Wire Plant) still bears traces of the factory; and some of the factories that built automobiles such as the Winton still stand. And, if you want to see the real thing at work, get someone to drive you down Independence Road in the Flats — you’ll be going through a major section of the ArcelorMittal mill. Or you can visit the neighborhoods built alongside the mills. Try Tremont – look at the architecture, count the churches, enjoy a meal at some of the best restaurants in Cleveland (and remember when you pay your bill, you’ve probably spent the equivalent of several weeks wages for someone who lived in that “hood” one hundred years ago). Of course, if you come back to the city after the convention you can buy a seat at a Browns-Steelers game. Try to remember that the roots of this contest are blue collar when you look at the tab!

But, if you are less adventurous, simply consult the online edition of the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Start with the article on iron and steel, and use the internal links to really get the full story of all the connections the industry has to the history of Cleveland.