5 Days That Shook City Council Plain Dealer November 15, 1981

An analysis of the failed attempt to wrest control of Cleveland City Council during November 1981

The first link is here

The second link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

5 Days That Shook City Council Plain Dealer November 15, 1981

An analysis of the failed attempt to wrest control of Cleveland City Council during November 1981

The first link is here

The second link is here

Michael R. White was Mayor of Cleveland from 1990-2002. He was interviewed for Teaching Cleveland Digital on July 24, 2013. Cameras by Jerry Mann and Meagan Lawton, Edited by Jerry Mann, Interviewed by Michael Baron. © 2013 Jerry Mann and Teaching Cleveland Digital.

Part one covers Mayor White’s formative years in the Cleveland neighborhood of Glenville, living in Cleveland during the election of Carl Stokes in 1967 and White’s election as the first African-American Student Union President at The Ohio State University in 1973.

Part two covers his work with Columbus Republican Mayor Tom Moody, his return to Cleveland, working with and learning from Council President George Forbes and his election to Cleveland City Council.

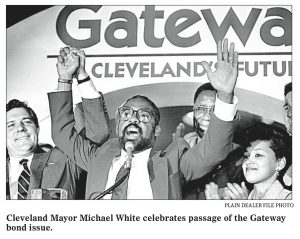

Part three covers the 1980’s in Cleveland when Mayor George Voinovich and Council President George Forbes were in power. White then speaks about being elected Mayor of Cleveland, and his first challenge as Mayor: the baseball team wants a new ballpark, so White spearheads the Gateway development.

From Wikipedia:

White, who grew up in Cleveland’s Glenville neighborhood, began his political career early on during his college years at Ohio State University, when he protested against the discriminatory policies of the Columbus public bus system and was subsequently arrested. White then ran the following year for Student Union President and won, becoming the college’s first black student body leader. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1973 and a Master of Public Administration degree in 1974.

After college, White returned to Cleveland. He served on Cleveland City Council as an administrative assistant from 1976 to 1977 and later served as city councilman from the Glenville area from 1978 to 1984. During his time in city council, White became a prominent protégé of councilman George L. Forbes. White then represented the area’s 21st District in the Ohio Senate, serving as a Democratic assistant minority whip.

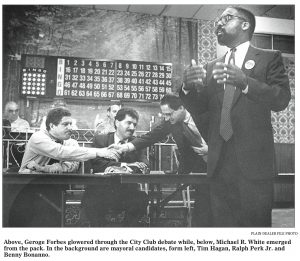

In 1989, White entered the heavily-contested race for mayor of Cleveland, along with several other notable candidates including Forbes, Ralph J. Perk Jr. (the son of former Cleveland mayor, Ralph J. Perk), Benny Bonanno (Clerk of the Cleveland Municipal Court), and Tim Hagan (Cuyahoga County commissioner). Out of all the candidates Forbes and White made it to the general election. It was the first time two Black candidates would emerge as the number one and two contenders in a primary election in Cleveland history.

In Cleveland, incumbent Mike White won re-election against council president George Forbes, who ran as the candidate of black power and the public sector unions. Angering the unions by eliminating some of the city’s exotic work rules, White presented himself as pro-business, pro-police and an effective manager above all, arguing that “jobs were the cure for the ‘addiction to the mailbox,'” referring to welfare checks. [1]

White ended up winning the race receiving 81 percent of the vote in predominantly white wards and 30 percent in the predominantly black wards.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_R._White

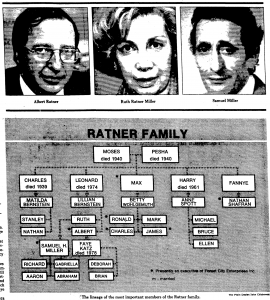

Ruth Ratner Miller obit from Plain Dealer 12/27/1996 newspaper

Ms. Rater Miller (1 Dec. 1925 – 26 November 1996)

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History listing

image from PD 6/8/1980

image from PD 6/8/1980

RUTH MILLER, A SERVANT OF THE CITY, DIES AT 70 `SHE NEVER ASKED FOR ANYTHING FOR HERSELF’ by Lou Mio

Ruth Ratner Miller broke the glass ceiling before anyone thought of the term to describe successful businesswomen.

She was president of Tower City Center, but business was only one aspect of the life of a woman who also dedicated herself to public service.

“She never asked for anything for herself,” said Gov. George V. Voinovich. “She was always asking, `How can I help? How can I help?’ She will be missed.’

Miller, 70, of Lyndhurst, died yesterday at Cleveland Clinic Hospital. She had cancer, a disease she had vowed to beat.

“She always assured me, `I’m going to recover from this and be all right,’ said Rabbi Armond Cohen of Park Synagogue, a lifelong friend. “I think she felt that way to the end.”

Miller, who had been fighting cancer for several years, was the eternal optimist, said Cohen. She had scheduled a party for Dec. 12.

“She was blessed with many gifts, but most remarkably, she shared most generously all the gifts that she had,” Cohen said. “She was a very great Jewish lady, a great citizen of the world and of her community.”

Her renovation of the Terminal Tower’s lower levels into a glamorous shopping center captured the city’s attention, but she also was instrumental in converting the former Halle Bros. Co. department store downtown into an attractive office building.

“She was a tremendous booster of Cleveland and understood the significance of relighting the Terminal Tower,” said Voinovich.

“That may sound insignificant, but Cleveland needed a symbol of its rebirth. On July 13, 1981, Ruth was responsible for relighting the Terminal Tower. It was a symbol the lights were back on in Cleveland and there was hope for a bright future.”

On a personal note, Voinovich added: “I’ll never forget how she responded when we lost Molly [their daughter, in an auto accident]. She was a prime mover in Janet and I receiving the Tree of Life Award from the Jewish National Fund, and was responsible for one of the largest recreation centers in Israel being named for Molly Agnes Voinovich. Ruth reached out to us at a time when we needed comfort.”

Miller, who never held elected office, was Cleveland’s community development director for Mayor Ralph J. Perk from 1976 to 1978 and director of Cleveland’s Health Department from 1974 to 1976.

“I have a new idea for saving neighborhoods,” she once said. “You start with people, not with buildings.”

When Miller was appointed community development director, Perk said: “She is more sensitive to people’s needs than any of the other candidates. That is one of the major requirements of being community development director.”

To carry out her goals, she worked 12 to 14 hours a day – spending much of the time out in the neighborhoods – and came to her office Sunday afternoons to catch up on correspondence.

Fridays, the Jewish sabbath eve, were always spent with her family, which had long been active in Park Synagogue.

Mayor Michael R. White said of her contributions to the city: “She was a passionate leader for assuring the health and well-being of Cleveland’s less fortunate and upgrading the quality of life for all of Cleveland’s citizens.”

At the national level, Miller was on the executive committee of the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and was a member of the Holocaust Memorial Council, appointed by President Ronald Reagan and reappointed by President George Bush.

“She had the longest tenure [at the museum], through two parties,” said Albert Ratner, her younger brother and co-chairman of the board of Forest City Enterprises Inc., where her uncle, the late Max Ratner, was board chairman. “She was the individual who was able to bring together the survivors and people in the community who had not been victims.

“Ruth was a tremendous advocate for women, not only in this country, but in Israel,” Ratner said. “She was a mentor and model, and she organized women to take their rightful place in the community.”

The Ratner family has long been active in supporting Israel. Family members have been prominent in raising money for Israel, as well as money for the Holocaust Museum.

Miller was born Dec. 1, 1925, to Leonard and Lillian Ratner, who founded the highly successful Forest City Enterprises Inc. The national real estate giant built and owns shopping centers, office towers, apartment buildings and hotels across the United States, including downtown Cleveland’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel.

She earned a bachelor’s degree in elementary education at Western Reserve University and a doctorate in guidance and counseling after the school had become Case Western Reserve University.

When she was 20, she married Samuel H. Miller, whom she had met at her family’s summer cottage in Wickliffe. Because she was a minor, she needed her parents’ written permission.

The couple had four children. Her marriage to Miller, who later became co-chairman of the board and treasurer of Forest City, ended in divorce in 1982.

Miller’s second marriage in 1985 was to Rabbi Phillip Horowitz, father of three children and rabbi of the former Temple B’rith Emeth. She retained the name Miller.

In 1980, she was the Republican candidate for the seat of retiring 22nd District Rep. Charles A. Vanik, but lost in the primary to Joseph Nahra by 1,500 votes.

She was elected chairwoman of the Greater Cleveland Convention and Visitors Bureau in December 1985.

She was a news analyst for WBBG-AM radio for two years, from 1978-1980, and was director of Rapid Recovery, a program aimed at cleaning up Regional Transit Authority right-of-ways, in 1979.

She co-chaired the campaign to elect Republican Thomas J. Moyer chief justice of the Ohio Supreme Court in 1986, when he defeated incumbent Frank D. Celebrezze.

Former Democratic Gov. Richard F. Celeste appointed her a trustee of Cleveland State University in 1987. She was an occasional lecturer in CSU’s College of Urban Studies.

As a trustee, she was chairwoman of the board’s minority affairs committee when CSU President John A. Flower fired Raymond A. Winbush as vice president of minority affairs and human relations.

In 1986, Celeste had appointed Miller to the Ohio High Speed Rail Authority, a group assembled to recommend ways to develop a passenger network linking the state’s major cities. Miller served as fund-raising chairwoman for the Greater Cleveland chapter of Aiding Leukemia Stricken American Children.

In 1985, she was appointed a member of the U.S. delegation to the World Conference to Review and Appraise the Achievements of the United Nations Decade for Women in Nairobi, Kenya. Maureen Reagan, daughter of then-President Reagan, headed the 34-member delegation.

Although Miller received many honors, she said she was especially proud of having been elected by her alma mater to the Cleveland Heights High School Hall of Fame in 1990.

Miller is survived by her husband, Rabbi Horowitz; sons, Aaron of Washington, D.C., Richard of Boston and Abraham of Cleveland; daughter, Gabrielle of Wellesley, Mass.; a brother; eight grandchildren; and five stepgrandchildren.

11 George Voinovich, former Cleveland mayor, Ohio governor and U.S. senator, dies Cleveland.com 6.12.16

Her charming openness and irreverence similarly pose at least a subliminal challenge to conspiracy theorists: Why would such a place as formidable as you imagine the PD to be

ever invite someone so full of the dickens as Mary Anne Sharkey to the table of senior management?It was an excellent question at the time, and all the more appropriate today. But the answer remains as elusive as Sharkey’s complicated internal role at the paper. After raising hell in Ohio politics for more than two decades — putting misogynist pols on the record to disastrous (for them) effect, helping install an improbable former street kid in Cleveland City Hall, and even helping snuff out an Ohio governor’s Oval Office ambition — Sharkey now finds herself in something of a state of internal limbo at “Ohio’s largest.” According to sources at the PD and among political communications people, she’s been stripped of her role as politics editor in all but name (a deve opment she’s not eager to discuss, but she doesn’t dispute). She’s an editor to whom no one answers. But she’s vowed to win the internal test of wills.

She’s prominent in nationa jiournalism circles: Village Voiceand Washington Post columnist Nat Henthoff singled her out for praise recently, and she serves on the board of the International Women’s Media Foundation, which is populated with nationally known media heavyweights. Because of her institutional memory and her wide name recognition throughout the state, “A Sharkey column mailed to 50 people around the state is a very, very powerful thing,” says Cleveland political consultant Bill Burges. “I mean, that is a Scud missile, or at least a

Patriot missile.” All of this surely provides her some internal leverage.

A MILD WORKAHOLIC whose schedule calls for frequent after-hours events and public appearances (including an occasional panel show on WVIZ-TV Channel 25), Sharkey does all her writing in her cramped office just off the newsroom. She shares a secretary with Metro editor Ted Diadiun and often has the television tuned to CNN. Colleagues with a weakness for practical jokes find her an easy mark: They have been known to hide her Rolodex and even her office sofa, waiting to see how long their absence will go unnoticed. She has a fiery temper that quickly blows over, and an impulsiveness that manifests itself in manic fits of shopping: She once bought a used Cadillac on a whim.

In early August, Sharkey arrives for an interview after attending a stormy press conference at Cleveland City Hall in which all of Mike White’s shortcomings finally broke into full public view. The woman who proved so instrumental to his election by engineering the PD’s endorsement must admit she’s concerned about White’s unsteady behavior: abrupt staff changes, almost comic micromanagement, and reports about general emotional instability following his effortless re-election last year.

“I’m starting to have my doubts,” she says about the mayor, which seems remarkably restrained after the months of mounting reports. Weeks later, after being pressed some more about her indulgent attitude toward White, Sharkey gets to the crux of her affection for the mayor: “I like overachievers,” she says, sitting in her brick, Lakewood home with one leg slung over her sofa arm. “And I think of myself as an overachiever. When I look at White, I just laugh. Other people think he’s arrogant, but he just amuses me. I see him as a ghetto kid … whose mother died at an early age.”

At a time in which many journalists — intimidated by their low public regard or perhaps by the doleful state of American libel law — have sought refuge in the euphemism, Sharkey continues to go for the political jugular. She can be delightfully caustic, at least if you’re not on the receiving end. She has referred to the prim members of the League of Women Voters as “the Democratic wives of Republican businessmen” and once likened a pair of arguing state representatives to a couple of skunks in a spraying match. “I never seemed to have learned the art of subtlety,” she once observed of herself in a column.

“[Sharkey] has the keenest news sense I’ve ever seen,” says former PD publisher Tom Vail. Even the people she criticizes, if not her more serious targets, voice genuine admiration. Ohio state Rep. and majority whip Jane Campbell says that Sharkey “has enough hope about the process to really make a difference.” U.S. Rep. Eric Fingerhut, who has also been batted around mildly but who on the whole has been well-treated in Sharkey’s columns, offers: “There’s no question that she’s sharp and caustic, but she doesn’t just go for the cheap shot; she puts it in context. Even though it always stings to be on the receiving end, I always get a sense that it’s coming from somebody with a little bigger picture, so it’s a little easier to take.”

Sharkey was raised in a reasonably prosperous Dayton family, the only daughter of a serially published Catholic writer who inhaled books until the day he died — writing at least two dozen himself (Norman Sharkey’s personal bestseller was a 1944 book about the papalselection process, “White Smoke Over the Vatican.”) Sharkey’s mother prayed to the Virgin Mary that she might deliver a girl after the first four attempts yielded all boys. She signaled her thanks by dressing Mary Anne in blue and white (the colors of the Virgin) until the age of 7.

The family was steeped in their father’s work: It became second nature for the older kids to issue opinions on the piles of manuscripts authors sent for his consideration while he was still on staff at a Catholic youth magazine. Most members of the family were even familiar with the symbols used in editing.

Though she’s had asthma all her life, Sharkey grew up a happy, energetic child who eagerly plunged into dance and piano lessons. Growing up second-youngest in a family with all brothers (one of her six brothers died recently; another, born with Down’s Syndrome, died before she was born), Mary Anne learned early how to get along amicably with the opposite sex. “I’ve never found men much of a mystery,” she says. It’s been a boon ever since to her formidable reporting skills, allowing her to coax information from male officials and propelling her into formerly all-male environments.

Her older brother Nick remembers that 3-year-old Mary Anne would walk around the house during Eisenhower’s first campaign saying, “I like Ike, I like Ike” (she even repeated it at her grandmother’s funeral). Her occasional child-modeling assignments through her Aunt Norma’s agency turned into more substantial teenage appearances in print and television ads for the Bob Evans restaurant chain.

Sharkey admits to having been “a very bad student” through her 16 years of Catholic schooling, terminating with an English degree from the University of Dayton. “I got out of college by the skin of my teeth,” she says. “That’s why I love newspapers, because you don’t need an attention span.”

Many years later, however, she learned that she suffered from dyslexia, a mild learning disability. “I sometimes reverse numbers, I mix metaphors, I could never learn foreign languages, and I absolutely don’t have any sense of direction. And I can’t do computers. Other than that, it hasn’t handicapped me.”

Yet it did leave her with a deep sense of having beaten the odds. “I was always in trouble for being an underachiever, and no one could understand why, including me.” Experts on the malady note that while dyslcxics do have trouble performing certain tasks, in other ways they often process information better, sorting through individual facts to identify patterns not readily apparent to others.

While still in college, she began her professional career as a copydesk clerk at Dayton’s old Journal Herald, an overachieving paper, largely Republican in editorial outlook though quite liberal in spirit, staffed by young journalists who were encouraged to report aggressively. Colleagues from her Dayton days uniformly remember Sharkey as a “live wire.”

“She had a phenomenal knack for getting politicians and policemen and judges to talk to her,” says Bill Flanagan, an editor who was perhaps her earliest mentor. Sharkey was so taken with the job that her brother Nick had to almost force her to complete school. At 24, she married Bill Worth, eight years her senior, twice previously married, and the paper’s city editor at the time. The pair tooled around town in a black Studebaker, which colleagues remember as being halfway between classic and junker. After four years, however, the couple divorced.

“Believe it or not, I was a tad naive in those days,” Sharkey says. “I was totally sheltered … I was the only one in my entire family to go through a divorce — cousins, aunts, uncles, brothers.”

Sharkey’s first taste of prominence grew out of an extraordinary event in the fall of 1974. She was covering the Dayton court system when two federal agents with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms got into a shootout in the Federal courthouse, killing one of the men. The following February, after having interviewed court sources and federal officials, Sharkey wrote a frontpage article describing how the suriving agent had refused his now-dead colleague’s offer to participate in an illegal chain-letter scheme and in selling confiscated guns, which led to their deadly encounter.

Separately, Sharkey’s Freedom of Information request had produced a court transcript in which the surviving agent described the events in chilling detail, full of rough language not ordinarily seen in any family newspaper, much less those in conservative, Southern Ohio towns. It included the key words: “Gibson, God damn it, you are fucking with my family. You are fucking with my future. I am not going to let you do it. I’ll kill you first.”

Unknown to Journal Herald editor Charles Alexander, the paper’s promotions department had arranged to distribute free copies of the paper that day to Dayton schoolchildren. In the ensuing uproar, Alexander was fired by the Cox chain, and his managing editor quit in protest. “That’s the story that people around here “I remember [Sharkey] for,” says former colleague Mickey Davis. “She proved her mettle.”

If the story inflicted collateral damage upon her superiors, Sharkey’s own career received quite a boost. The unique controversy became fodder for national journalism trade journals, and by 1977 she had been made an investigative reporter. A year later, with an opening in the paper’s one-person Columbus bureau, she moved to the capital, where her energy and charm quickly won her admission to the mostly male “Capital Square Gang,” a collection of politicians, journalists and lobbyists who would often gather at the Galleria, a bar a across from the Statehouse.

“TheJournal Herald clearly got a lot of stories because she would go to where these people did business,” says one PDreporter. “And to a [House Speaker] Vern Riffe, cutting part of the deal at the Galleria was just as important as finishing the deal at the Statehouse.”

In 1980, she remarried, to Joe Dirck, who today is a PDcolumnist himself At the time, he was a fellow Daytonian who’d played rock ‘n’ roll in area nightclubs. Sharkey and Dirck shared an obsession for politics and, one colleague jokes, questionable fashion sense. Old photos from the Dayton newspaper archives show Sharkey dressed in blouses with enormous period-piece

lapels, her hair worn in cascading bluffs framing her face. One office intern from that time remembers the effect her appearance left from their initial meeting. “Here I was this scared

college student, and she was wearing purple gaucho pants and a puffy cap. I thought I was about to be employed by Petula Clark.” Dirck still had in his possession a pair of skin-tight, leopard spot pants from his days as a rocker.

Characteristically, they met during the heat of a reporting battle: It was the mid-’70s. Dirck was reporting for a small daily in Springfield. He and another reporter were investigating a bookkeeper for a federal, anti-poverty agency who had a gambling problem. When the case landed in a federal grand jury, Dirck thought he’d go down to wait outside the closed session to see who came and went. “This assistant U.S. attorney — who I don’t know — they called him Crimefighter, [he was a] spit and polish, kind of hard-nosed type — started giving me a hard time, told me I couldn’t stand in the hallway,” Dirck recalls. “I said, ‘Well, this is a public building.’ He said, ‘Well, you can’t stand here, you have to go down in the lobby.'”

So Dirck went downstairs to a pay phone and called Sharkey, whom he knew only by reputation. “She was kind of a legend in Dayton at the time I said, ‘hey, this guy told me I couldn’t stand in the hallway.’ And she said, ‘WHAT? I’ll be right over.'”

Sharkey showed up after having scooped up a handful of other print reporters and a couple of television crews. “The Crimefighter came out, and he knew he couldn’t buffalo them,” says Dirck. “So he just went back in the room.”

During the early years of their marriage, Sharkey was continuing to produce powerful reporting. But as the Reagan era dawned, it was her role as feminist pathbreaker that was gaining the most attention. In 1981, she was sitting in the Secretary of State’s office after an election when an official of the Ohio Democratic Party, Pat Leahy, began to brag about beating Issue 2 and its proponent, Joan Lawrence (then head of the state League of Women Voters and now a state representative from Galena) and “her fat, ugly tits.” When Sharkey reported the comment (“I didn’t get the word tits in, but I think readers could tell what I meant,” she says), Leahy was fired, and Sharkey became something of an instant feminist poster girl.

“That was sort of a watershed for me,” Sharkey says. “I sort of once in a while feel like there is something to this diversity. There were six guys sitting around laughing. And it didn’t occur to any of them to report it.”

“She’s the one who said, ‘Now wait a minute: there’s this loudmouth with the Democratic Party, and nobody’s doing anything about it. I’m going to do something about it,'” recalls Gerry Austin, who cut his political teeth in George McGovern’s 1972 Ohio campaign and later ran campaigns for Dick Celeste, George Forbes and Jesse Jackson.

Curiously, she became a lightning rod for feminists even when she didn’t intend to. During the ’82 gubernatorial election, Sharkey arrived for an interview with Republican Clarence J. “Bud” Brown and was greeted with the suggestion that she “step into my parlor and take off your clothes.” Having grown up with plenty of verbal abuse from her brothers, she says, she never took it seriously and wrote it off as a grossly awkward attempt at humor by a normally buttoned-down man. She later mentioned it in passing to press colleagues, and a Cincinnati Enquirer reporter used it as a small item. “And Lord, it started from there,” recalls Dirck.

The New York Times picked up on it, which led a biting press release from the National Organization for Women, which prompted feminist picketing of Brown. The libertarian candidate seized on the remark, demanding an apology on behalf of women, and the Celeste campaign privately enjoyed the problems it was causing its rival. Brown later asked if he should apologize to Sharkey’s husband.

At the center of it all was Sharkey, the congenitally amiable Catholic girl with impeccable manners tempered by a bawdy sense of humor — highlighted by her endearing “horsey laugh,” as one friend puts it — who once again was thrust into the role of “feminist hero.” “Everyone assumes I’m going to come from this liberal-Democrat, feminist point of view,” she says today. In truth, she contends, she’s a feminist “when I need to be.”

In 1983, partly as a result of the attention from the controversy but also due to her warm conviviality with friend and foe alike, she was elected president of the Ohio Legislative Correspondents’ Association, the first woman so named in the group’s nearly 100 years of existence.

That same year, she was hired by the PD to join the paper’s Columbus bureau. Her days of real prominence were at hand. By one account, it was a 1981 series where she wrote about racial tensions at the Lucasville prison that got her noticed in Cleveland and later hired at the Plain Dealer.

Richard F Celeste, the 64th governor of Ohio, and Mary Anne Sharkey, then-Plain Dealer reporter and later Columbus bureau chief, began on friendly enough terms. Like many reporters who covered Celeste in his early years, Sharkey was filled with high expectations formed by the candidate’s own soaring campaign rhetoric as well as the fact that he was following eight years of antics by boorish Jim Rhodes. After that, much of the capital press pool was easy prey for the jarring contrast provided by the earnest Yalie governor with ethnic roots and an Oxford pedigree. The stage seemed set for a four-year run of Camelot By the Scioto. What developed followed quite another script.

Eventually the Celeste administration came under a steady and perhaps well-deserved working-over by the PD bureau. Sharkey’s tips, reporter Gary Webb’s bulldog tenacity and the PD’s willingness to print the results were turning up a Niagara of administration sleaze that cried out for coverage, especially considering the rest of the state’s papers were so timid about taking on a sitting governor. “Once people know you’ll go with that stuff, it becomes self-generating. It began coming in over the transom,” one reporter explains.

Sharkey readily concedes that the PD’s Columbus bureau under her direction didn’t cover the legislature very critically. She could hardly argue otherwise. It would be up to the Akron Beacon Journal to devote resources later in the decade to document Riffe’s questionable fundraising methods in its so-called “pay~for-play” series.

In the spring of 1987, after Democratic front-runner Gary Hart was forced to drop out of the presidential race because of his extramarital affairs, Sharkey turned her attention to the rumors about Celeste’s similar activities. She pulled the personnel files of two aides he was said to be sleeping with. Two other Columbus reporters were working on the story, but Sharkey had personal knowledge of Celeste’s peccadilloes with a woman she knew.

“We just thought it was incredible that Celeste would run for president when he had the same womanizing problem as Hart,” says Jim Underwood, at the time a Columbus-based reporter for the Horvitz newspapers, who later joined the PD.

In early June ’87, Underwood entered a Celeste press conference and sat between Sharkey and the Dayton Daily News‘ Tim Miller, who was also digging around the edges of the story. ” I just kind of grinned and said, ‘One of us is gonna have to ask the question.’ And we all knew what I was talking about,” says Underwood. Miller pulled out a dollar and challenged Underwood. Sharkey added a quarter. And Underwood got up, still clinging to the $1.25, and asked the question that would soon reverberate around the country. “Governor, is

there anything in your personal life that would preclude you from being president, as it has Gary Hart?” When Celeste surprised everyone, including his aides, by choosing outright denial

over dodge, Sharkey had a hook for her story. Media people would later say that Underwood held Celeste’s jaw while Sharkey slugged it.

In a copyrighted, front-page article on June 3 written by Mary Anne Sharkey and Brent Larkin, the PD reported that Celeste had been “romantically linked to at least three women” in the last decade, and called into question his credentials to be president. Says Larkin: “We knew it wouldn’t be ignored by the national media, coming on the heels of the Gary Hart incident.”

He was right. The Celeste story quickly became national news. And even though much of the coverage was harshly critical of the PD, the damage had nevertheless been done: Celeste never quite recovered his prior stature as a regional politician at the threshold of national prominence. (Celeste’s office didn’t return calls for comment.) And the legal saber-rattling of Stan Chesley — a well-connected Cincinnati personal-injury attorney and major Celeste donor who, former Celeste aides confirm, was aggressively encouraging the governor to file a libel suit — eventually sputtered out. Sharkey’s reputation received yet another high-octane boost.

Months after the Celeste story, the Plain Dealer promoted Sharkey to the deputy editorial page director, and Sharkey moved to Cleveland. Dirck, who had spent some time working at a Columbus television station after the Columbus Citizens Journal closed, eventually followed his wife 120 miles north to write a much-coveted column, sparking more than a little internal bitterness over the perceived two-for-one deal. Sharkey’s new position seemed an unlikely fit for many who knew her, given her interests and her well-known impatience with both the nonpolitical aspects of government and with sitting behind a desk. “I thought it was strange,” says her Dayton editor Bill Flanagan. “Well, I thought she was getting older and wanted something different. But it didn’t fit the Mary Anne that I knew.”

Nevertheless, she thrived. The page, significantly enlivened under her predecessor, continued to be relatively bold and unpredictable, at least for the traditionally cautious Plain Dealer. It took several brave stabs at the polarizing issue of abortion, an issue on which Sharkey shares Mario Cuomo’s position: She is personally opposed to it, though she refuses to impose her personal beliefs on the rest of society. It also denied Lee Fisher the paper’s endorsement in his initial run for Ohio Attorney General because of his embrace of the death penalty. Internally, Sharkey employed her people skills to defuse potential ideological conflict.

But her tenure on the editorial page will be best remembered for the paper’s endorsement of Mike White during the 1989 mayoral race. Sharkey persuaded publisher Tom Vail to ignore the near-unanimous pleas of Cleveland’s establishment on behalf of George Forbes, and instead anoint a smoothly articulate black state representative and former Cleveland city councilman from Glenville, whom Sharkey had observed with some admiration while in Columbus. “Vail, in his last days, tended to defer to Mary Ann’s good judgment,” recalls one editorial board member at the time. “She was the mover in it, and Vail largely blessed it.”

The insurgent White campaign, running third at the time behind both Forbes and Benny Bonnano, learned of the endorsement the day before it ran, and immediately understood its importance. “The Plain Dealer likes to take credit for shaping the course of the city,” says White’s ’89 campaign manager Eric Fingerhut, “and that’s a case where they did.”

But at the PD, where the saying goes “The closer you are to the top, the closer you are to the edge,” no one is ever surprised by frequent management shakeups. And Sharkey’s internal stock ebbed after Vail retired. Her legendary shouting matches, during the ’89 mayoral race, with editor (and Forbes partisan) Thom Greer didn’t help. Of her high-decibel confrontations with Greer, she says: “I knew I would be hurt by that, and I was.”

The shift from Vail’s moderate, Rockefeller-style, noblesse oblige brand of Republicanism to Machaskee’s harsher, in-your-face, Pat Buchanan style demanded a less-unpredictable editorial voice for the paper. So Sharkey was replaced on the editofial page by Brent Larkin, a lawyer and a former Cleveland Press political writer with a deeper knowledge of Cleveland and a far more pleasing posture toward management.

Sharkey was given what most of the world would consider an equally prominent assignment. She was made assistant Metro editor just as the paper began its expensive and oft-chronicled move to the suburbs with the opening of several exurban news bureaus. While she was now responsible for directing nearly 100 reporters, at least one colleague calls that position a form of “internal exile,” with only modest direct impact on the news product but lots of time spent overseeing budgets and making sure that slots were covered when copy editors called in sick — hardly her strength.

At about this same time, Sharkey was dealing with a series of personal setbacks that were disrupting her emotional equilibrium. As she and Dirck (who has a college-age daughter by a previous marriage) moved into their 40s, their efforts to adopt a child met with frustration. Once, an adoption was scotched at the last moment when the pregnant woman’s boyfriend called their attorney from the delivery room. They were set to adopt a second time, this time a biracial child, but that, too, fell apart at the last minute. By 1991 Dirck had a mild stroke, which put things off again, and by the time he recovered, the couple, then nearing their mid-40s, were informed they would have to abandon their adoption plans.

“What can I say?” Sharkey says, her eyes misting. “After awhile, you just say to yourself, ‘It’s not meant to be.’ Her brother Nick calls it “the tragedy of her life. She’s told me a million times that you can have a million [newspaper] clippings over in the corner, but giving life to a child…”

Sharkey eventually asked to be replaced in the Metro editor’s position, which seemed too much to handle with all the other noise going on in her life. “Metro editor was the most miserable job I ever had in my life. It had everything to do with management and nothing to do with news.” She learned that she was born to report and write, not oversee others. Hall immediately carved out her current “politics editor” role, which defies standard organizational-chart description. Meanwhile, her personal losses have continued. After losing one brother before she was born and then her mother to brain cancer in 1976, Sharkey’s father and another brother died last year. “Those losses have been finding their way into her writing,” her husband says. Earlier this year, for instance, she wrote an emotional column about her brother’s death, briefly confessing to her own spiritual shortcomings as she described the loving community that enveloped her brother with care in the final days of his life.

Despite all the tensions, Sharkey has been given considerable breathing space and wide latitude to roam at the PD. And her “feminist” accomplishments have continued. Sharkey’s most immediate project has been encouraging more management openings for women. She and an informal assortment of female editors and managers have been gathering over occasional lunches and dinners to discuss the issue. “Immediately people became threatened by it, like we were holding a civil rights rally,” she says. And women are increasingly being added to the paper’s management ranks (one female editor of 17 years, Marge Piscola, has recently been promoted to the new position of news editor, where she’s now centrally responsible for planning Page One; and nearly everyone in a position to judge thinks PD editor David Hall has a genuine commitment to addressing documented complaints about gender inequities.)

Sharkey herself sits in editorial planning meetings when her ambitious reporting schedule allows, and she still has a place on the paper’s executive council. She also has the ear of PDeditor David Hall, according to Hall himself.

“She has unique skills and insights that were especially important for me, coming into Ohio from outside the state to edit the state’s largest newspaper,” Hall says.

Cleveland.com profile of Cleveland attorney Fred Nance October 12, 2008Fred Nance has crossed boundaries both real and symbolic

“See those boys on bicycles?”

Fred Nance, one of the region’s most powerful and influential citizens, eased his tan Escalade to a stop. He pointed at the trio of black boys pedaling furiously through an intersection near the Cleveland-Shaker Heights border.

Nance grinned and waved at the passing parade. They looked like city kids, not yet teenagers, racing home after a suburban adventure.

He didn’t know them, but he recognized them.

“There was me when I was their age,” Nance said. “That’s exactly what we used to do.”

His eyes followed as the boys disappeared into the streetscape, taking with them any chance to learn their past or witness their future.

“I used to ride my bicycle from East 135th Street and Kinsman, where we lived, to Shaker Heights,” he said. “I knew there was a different world than the one I saw every day in my neighborhood. I caught a glimpse of it, through the trees and across the lawns as I pedaled along South Park Boulevard, just like them.

“And I’d say to myself,” he continued in a low voice from a long-gone time, ” ‘Someday, I’m going to be a part of that world, too.’ “

Let the record show: Fred Nance has arrived.

Regional managing partner at Cleveland-based Squire Sanders & Dempsey, one of the globe’s whitest-shoed law firms, Nance, 55, is a confidante to mayors and the go-to guy for nearly every civic project that’s come Cleveland’s way during the past two decades. He is one of this region’s most recognized and influential citizens.

That’s the public side. In private, Nance is one half of a civic-minded couple. His wife, the former Jacqueline Jones, heads the LeBron James Family Foundation, an Akron-based group that helps children and families in Northeast Ohio. Both husband and wife are high-profile attorneys.

Fred’s working-class childhood shaped his life. Jakki, as everyone calls her, grew up in comparative affluence. As a married couple, they complement each other. She’s the playful, outgoing and social counterpart to his more serious, studied and practical personality. Both are committed to improving the region.

Venturing beyond racial borders

Nance was set on his path during the long, violent summer of 1966.

In a social experiment that preceded Cleveland’s failed school-desegregation efforts, Jesuit priests recruited 12-year-old Nance to attend St. Ignatius High School on the near West Side.

“Even though I was far and away the best student at my inner-city grade school, I wasn’t deemed to be quite up to their standards,” Nance said. “So after I applied and was accepted to St. Ignatius, I had to take remedial classes that summer to get into the school in the fall.”

This was years before busing became the long-running court case that Nance would argue against on behalf of the Cleveland School District in federal courts. No, at this moment, Nance found himself waiting at the intersection of East 55th Street and Woodland Avenue for a bus to take him across the Cuyahoga River and the city’s racial borders of east and west, black and white.

For six days during that summer, rioters burned and looted in the Hough neighborhood after racially charged clashes between a white business owner and black customers. Young Fred watched in awe as National Guardsmen with fixed bayonets rode past in military halftracks on their way to engage the rioters.

“I watched guys come out of stores and smash the windshields of cars with sledgehammers and throw bricks through store windows,” Nance recalled. “I’m just a 12-year-old kid, standing on the corner and thinking: ‘There’s got to be a better way.’ I wanted to empower myself so that this wasn’t what I or the people I loved have to resort to.”

Right then, Nance made a promise to himself.

“I figured out, standing on that corner, that the advantages in life must go to the people who understand the rules of the game and who are in a position to manipulate them,” he said. “I decided then I wasn’t going to be a powerless victim, and I figured that being a lawyer was the way to go.”

He entered St. Ignatius that fall at the bottom of his academic class. Four years later, he graduated with an A average and rejected full scholarships to Princeton and Yale for one to Harvard.

“A lot of what followed for me happened as the result of the transition from one world to another that took place at St. Ignatius,” Nance said. “It wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t especially easy socially.”

After graduating from Harvard and the University of Michigan Law School, Nance returned to Cleveland in 1978, joining Squire Sanders & Dempsey as one of the few black associates at the firm. In 1987, he became a partner.

His life and career took a dramatic turn in 1991 when Cleveland Mayor Michael R. White needed a lawyer to represent him in a grand jury investigation. White wanted Charlie Clarke, then the dean of Squire Sanders trial attorneys.

White settled on Nance only after Clarke canceled appointments with the mayor and sent the young and promising black lawyer in his place. As Nance recalled, Clarke’s motive was to give him an opportunity that would promote his career. It worked to perfection.

“At first Mike wasn’t all that impressed with me,” Nance said. “But in time it clicked. He started asking me to work on different legal matters for him.”

Two years after that rocky start, White called Nance to ask him to negotiate a lease for him.

“I told him the only experience I had with that was signing a lease on an apartment when I was in law school,” Nance said, laughing at the memory. “He said just take care of this for me.”

The lease turned out to be the contract between the city and Art Modell, who wanted to move the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore. When the legal wrangling ended, the team had moved, but the city kept the Browns’ names and colors and the promise of a new team in 1999.

That legal work thrust Nance into the big time, and he bloomed as the go-to lawyer in Cleveland.

In the early 1990s, he was working on the busing case when he met Jakki. His first marriage had ended after 10 years. Jakki, too, was divorced and working for another law firm.

Their courtship is the stuff of family lore. Thrust together on the legal project, the two lawyers huddled over one-on-one lunches. Following each meeting, she billed him for her time. She was completely unaware that Nance scheduled the get-togethers to get to know her better.

Eventually, Nance came clean.

“Jakki,” he told her, “I keep asking you to lunch because I like you. And, would you please stop sending me these bills afterwards?”

Determination born of adversityJakki had a more privileged childhood than Nance, but a more stressful and dangerous one as well.

Her father is Dr. Jefferson Jones, a nationally recognized oral surgeon, who wanted nothing but the best for his two adopted children: Jeff and Jakki. The family lived in affluent white communities where they weren’t always welcome.

Jakki Nance, 42, remembers racial attacks and social ostracism that dogged her and her family as they integrated predominantly white neighborhoods and schools.

Vandals struck their home repeatedly when they moved into Pepper Pike. Someone broke the tops off three driveway light poles. The house was egged. Eventually, the night marauders fired shots into the house.

Jakki said it scared her, but not her father, who armed himself and refused to leave.

“He had been in the Army and was determined to protect his family,” she said. “As a child, I felt protected by my father even though I hated we had to go through all that.”

Her father wanted her to become a doctor, but she pursued dance before deciding to become a lawyer.

Her years at Orange High School were filled with confrontations with white teachers who doubted her intelligence and black and white classmates who shunned her. Only after leaving Ohio in 1984 to attend Spelman College, the predominantly black women’s school in Atlanta, did she find a sense of self and acceptance.

“At Spelman I was happy,” she said during a recent interview as she picked at a green salad on the patio of a suburban East Side restaurant. “It was the first time in my life I was judged on my work instead of who I was.”

Jones, now retired, said his daughter’s childhood experiences made her determined to succeed.

“She had the attitude that nothing would stop her from what she wanted, that she would show everybody what she was made of,” he said.

She returned to Cleveland after college and entered law school at Case Western Reserve University. By the early 1980s, she was working in a family friend’s law office and seeking ways to make a mark in the city.

She and Nance were married by White in 1999.

Jakki Nance has been instrumental in turning around the disorganized LeBron James Family Foundation. Under her direction, the foundation has formed closer ties with local businesses and created profitable projects like an annual bike ride for charity.

The couple agree that their lives far exceed anything they ever imagined as youngsters.

“I’m one of the luckiest people I know,” Fred Nance said. “But I believe you make your own luck. I always wanted to be successful, but I didn’t know what success would be or look like.”

When the National Football League needed a new commissioner a year ago, Nance’s name was on the short list.

John Wooten, chairman of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, a Washington, D.C.-based group that advocates for greater diversity in professional football, said the organization recommended Nance for the job because of his role in bringing a new team to Cleveland after Art Modell moved the Browns to Baltimore.

“Fred Nance was a guy who’s a great lawyer and we felt helped us save Cleveland and save the Browns for Cleveland,” said Wooten, who played on the Browns’ 1964 championship team.

While the couple toyed with the idea and enjoyed the attention, neither Fred nor Jakki was eager to leave their comfortable lives in Cleveland.

Currently, Nance is neck deep in negotiations to secure a Medical Mart/convention center as the curative to an ailing downtown.

Why is Nance the go-to guy on so many civic projects?

Tom Stanton, chairman of Squire Sanders & Dempsey, thinks it’s something simple, elemental and rare. “People trust him,” he said.

“It’s a chemical thing,” Stanton said, over coffee and dessert at a dinner party in Nance’s home for the firm’s summer associates. “I don’t know how to explain it, except to say he has this natural sense of empathy that compels people, and I mean everyone, blacks and whites, young and old, to be comfortable around him.”

<class=”caption”>The Fred Nance File

For nearly 30 years, Fred Nance has been involved in a battery of legal matters at Squire Sanders & Dempsey that defined and shaped Greater Cleveland. Here’s a partial list of some of his highest-profile cases and negotiations:

• 1979 — Carnival kickbacks — As a first-year associate, Nance joined the trial team that successfully represented George Forbes against accusations that the then-Cleveland city council president had accepted payoffs from a local carnival operator.

• 1991 — Doan and Beehive school projects — A county grand jury investigated whether then-Mayor Michael White had, as a councilman eight years earlier, used his position as a city councilman to aid the development of real estate projects in which he was an investor. White wanted the top trial lawyer in the city to represent him. Instead, the law firm sent Nance. The grand jury never charged White, and the two men became friends. For Nance, it was the start of a relationship and an entree to a series of lucrative legal contracts with the city.

• 1995 — Cleveland Browns — Nance represented the city in a lease dispute with Browns owner Art Modell, who was in the process of moving the team to Baltimore. The Browns were forced to delay their move and to leave all team colors, names and trademarks in Cleveland.

• 1991-96 — Busing — Nance represented the Cleveland School District, on behalf of White and a group of black community leaders, seeking to release the schools from court-ordered busing. After years of legal wrangling, a federal court ruled in 1996 to allow the district to assign pupils “with its best judgment rather than complying with a court-ordered mathematical formula for racial balance.”

• 1997 — Concourse D — Nance negotiated a 30-year lease of the new concourse with Continental Airlines, a $100 million investment that ensures Cleveland Hopkins International Airport remains a Continental hub.

• 2001– Brook Park land swap — Though many other attorneys were involved in the decade-long litigation over the controversial decision to swap land and municipal boundaries between Cleveland and Brook Park, Nance claims credit for settling the matter. The deal allowed construction of an extended runway at Hopkins.

• 2003 — The throwback jerseys — Nance had no clue who LeBron James was, but agreed to help the high school basketball player at the request of a friend. James faced suspension from the state championships because he accepted two vintage basketball jerseys worth about $845 from a clothing store. Nance won in court, allowing James to lead his team to the state title in his senior year. Nance’s wife now heads James’ foundation.

• 2005-2006 — DFAS — Nance led the successful effort to retain 1,100 jobs at the Defense Finance Accounting Services Center in Cleveland.

• 2007-present — Medical Mart — Nance spearheads the ongoing talks to develop a new convention center and medical mart in downtown Cleveland.

Plain Dealer News Researcher JoEllen Corrigan contributed to this report

</class=”caption”>

Comfort zone without boundariesThis is no small feat and, in large measure, is the real secret to Nance’s success. In a hyper-segregated, class-stratified city, where East rarely meets West and wary tribes mingle at arm’s length, Nance is expert at crossing boundaries.

Or, to put it another way, Nance never lost the feeling of freedom, just like the carefree boys on bicycles, that comes with racing across the sharp and bright lines dividing one part of Cleveland from another.

To that end, he added, it’s important that he and other black professionals hold themselves up as examples.

“If you don’t see people who look like you, people who started out where you started out, it is not an irrational conclusion to draw that it is impossible to try and work within the system,” Nance said. “That’s why it’s very important to show African-Americans who have done things right and are enjoying the benefits.”

Nance makes crossing boundaries appear effortless and perfectly natural. To watch him work a room — whether at an all-black social gathering, a racially mixed civic meeting or formal presentation where he’s the only African-American — is like watching a skilled athlete going through practiced repetitions.

“My forte is dealing with difficult people in stressful circumstances to come out with a positive result,” he said.

None of this is easy. Years of preparation and practice — along with setbacks and miscues — precede the performances that make fans cheer and detractors jeer.

And he does have detractors. Though few of them are willing to say so out loud or in public.

“I’m so sick of hearing about him,” said one black Cleveland attorney, who admitted to being more than a little envious of the glowing media attention that sticks like cellophane to Nance. “He’s a good lawyer, but there are so few of us out here and he’s like the only one that everybody knows and talks about. That can get to be old and a bit too much to swallow.”

Nance has heard such talk.

“People don’t say that to my face, but they say it around mutual friends, and it gets back to me,” he said, adding there are others who say even worse. “Then, there’s a group that says I’m a tool of the establishment, just like every other fat cat profiteering off the backs of the people.”

After recounting these critical comments, Nance laughed and said there might be a bit of truth to them.

“It’s obviously ironic to me, given where I started,” he said, still chuckling. “Maybe, it’s deserved because I certainly have benefited from being a part of the system. But I honestly believe I’ve had the opportunity to do the public good that I’ve always dreamed of and I have a good life, too. It’s the best of both worlds.”

Nance recently joined a dozen professional black men on a stage at Audubon School, a public elementary school not far from his old neighborhood. One by one, the men — doctors, engineers, college professors and lawyers — described their occupations to the kids, who sat in wide-eyed wonder at the idea of people who look like them doing unimaginable things.

When his turn arrived, Nance spoke without a microphone, projecting his deep voice to the back of the auditorium.

“I was raised right around the corner from here, at 135th and Kinsman, and I’m a lawyer,” Nance said. “I represent a young man you all know named LeBron James . . . “

Nance paused for dramatic effect, as the kids perked up at the name of the famous basketball star.

“I’m here today because I need one of you to come and take my place one day.”

The auditorium exploded in cheers as the kids stood to applaud. And Nance, beaming just as he had when the boys on the bicycles crossed his path, crossed yet another boundary, pressing his own childhood dreams onto the next generation.

1 The Michael R White Interview (video)

2 Mayoral Administration of Michael R. White from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

3 Michael R. White From Wikipedia

4 Cleveland Reacts to Call For Unity (Philadelphia Inquirer 10/26/89)

5 Stepping Down – from Cleveland Magazine

6 “The private side of a public man: Michael White” 1990 Cleveland Magazine by James Neff

George Voinovich, former Cleveland mayor, Ohio governor and U.S. senator, dies Cleveland.com 6.12.16

A Photo History of Cleveland’s Playhouse Square; Rise, Decline and Rebirth 5.27.16 Cleveland.com