Garrett Morgan’s long road to inventing the modern-day traffic light

by Alanna Marshall

The link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

Garrett Morgan’s long road to inventing the modern-day traffic light

by Alanna Marshall

The link is here

Cleveland Public Library (top) George Myers/WRHS (bottom)

Cleveland Public Library (top) George Myers/WRHS (bottom)

The Best Barber in America

By John E. Vacha

When Elbert Hubbard called Cleveland’s George Myers the best barber in America, people listened.

Hubbard’s was a name to be reckoned with in the adolescent years of the Twentieth Century. His Roycroft Shops in New York were filling American parlors with the solid oak and copper bric-a-brac of the arts and crafts movement. His periodicals, The Philistine and The Fra, brought him national recognition as the “Sage of East Aurora.” One of his essays alone, “A Message to Garcia,” ran through forty million copies.

You could say he was the Oprah of his day.

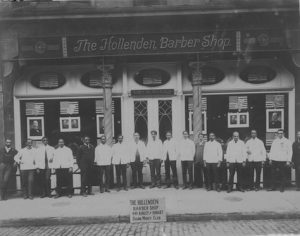

Myers himself was certainly aware of the value of a testimonial from Elbert Hubbard. Across the marble wall above the mirrors in his Hollenden Hotel establishment, he had imprinted in dignified Old English letters over Hubbard’s signature, “The Best Barber Shop in America!”

Though he played on a smaller stage, George A. Myers managed to compile a resume as varied and impressive as Hubbard’s. He was recognized as a national leader and innovator in his profession and became one of the most respected members of Cleveland’s black bourgeoisie. As the confidant and trusted lieutenant of Mark A. Hanna, he became a force in Ohio Republican politics. Behind the scenes, he campaigned effectively to maintain the rights and dignity of his race. In later years he maintained a voluminous correspondence with James Ford Rhodes, providing the historian with his inside knowledge of the political maneuvers of the McKinley era.

It wasn’t a bad record for a barber, even for one who had bucked his father’s wishes for a son with a medical degree. George was the son of Isaac Myers, an influential member of Baltimore’s antebellum free Negro community. Like Frederick Douglass, the senior Myers had learned the trade of caulker in the Baltimore shipyards. When white caulkers and carpenters struck against working with blacks, Isaac took a leading role on the formation of a cooperatively owned black shipyard. He became president of the colored caulkers’ union, and that led to the presidency of the colored wing of the National Labor Union.

Born in Baltimore in 1859, George Myers was ten years old when his mother died in the midst of his father’s organizing activities. Isaac took George along on a trip to organize black workers in the South and then sent him to live with a clergyman in Rhode Island. George returned to Baltimore following his father’s remarriage and finished high school there but found himself excluded from the city college because of his race.

That’s when George decided to call a end to his higher education, despite his father’s desire that he enroll in Cornell Medical School. After a brief stab as a painter’s apprentice in Washington, he returned to Baltimore to master the barber’s trade.

Young Myers came to Cleveland in 1879 and found a job in the barber shop of the city’s leading hotel, the Weddell House. He had come to the right place at the right time. Cleveland was in the midst of its post-Civil War growth, and its barbering trade was dominated by African Americans. Myers soon became foreman of the shop, and among the influential patrons he serviced was the rising Republican politico, Mark Hanna.

His upscale clientele served Myers well when a new hotel, the Hollenden, challenged the supremacy of the Weddell House. The Hollenden’s owner was Liberty E. Holden, publisher of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, who advanced Myers four-fifths of the capital required to operate the barber shop in his hostelry. The remaining $400 was provided by a select group which included Hanna’s brother Leonard, his brother-in-law Rhodes, ironmaster William Chisholm, and future Cleveland mayor Tom L. Johnson. “Suffice to say that I paid every one of you gentlemen,” Myers later recalled to Rhodes with pardonable pride. Once again, Myers had made a good career move.

Located in the booming downtown area east of Public Square, the Hollenden quickly became the gathering place for the city’s elite as well as its distinguished visitors. One of its premiere attractions undoubtedly was the longest bar in town. Another was its dining room, which was appropriated by the politicians and reputedly became the incubator of the plebian ambrosia christened “Hanna Hash.”

When not eating or drinking, politicians naturally gravitated to the hotel’s barber shop, which, like politics, remained a strictly male domain in the 1880s. Myers served them so well that in time a total of eight U.S. Presidents, from Hayes to Harding, took their turns in his chair, along with such miscellaneous luminaries as Joseph Jefferson, Mark Twain, Lloyd George, and Marshall Ferdinand Foch. As for the regulars, according to the eminent neurosurgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing, it became “a mark of distinction to have one’ s insignia on a private shaving mug in George A. Myers’s personal rack.”

In such a milieu, it was almost inevitable that Myers himself would get involved in “the game,” as he called politics. Mark Hanna had hitched his wagon to a rising star in Ohio politics named William McKinley and invited Myers on board for the ride. As a Cuyahoga County delegate to the Ohio State Republican Convention, Myers helped nominate McKinley for governor in 1891. He supported the Ohioan for President as a delegate to the Republican National Convention the following year. McKinley fell short that time, but Myers cast the deciding vote to place a McKinley man on the Republican National Committee, giving the Hanna forces a strategic foothold for the next campaign.

As the crucial campaign of 1896 approached, Hanna decided that Myers was ready for greater responsibilities. A vital part of Hanna’s strategy to secure the nomination for McKinley involved capturing Republican delegations from the Southern states. Since most white Southerners at the time were Democrats, blacks enjoyed by default a disproportionate influence in the Southern Republican organization.

That’s where Myers came in, as the Cleveland barber undertook to organize black delegates for McKinley not only in Ohio but in Louisiana and Mississippi as well. The convention took place in the segregated city of St. Louis, where Hanna further entrusted Myers with the delicate task of overseeing accommodations and providing for the entertainment of the colored delegates.

McKinley, of course, won not only the nomination but went on to take the election. Hanna then had Myers installed as his personal representative on the Republican State Executive Committee, where Myers worked to integrate the Negro voters of Ohio into the Hanna machine. One of Myers’ guiding principles was the discouragement of segregated political rallies in order “to demonstrate that in party union there is strength.”

Myers had developed a deep personal attachment to Hanna, whom he affectionately dubbed “Uncle Mark.” “His word is his bond and he measures white and black men alike, — by results,” wrote Myers of his political patron. “He is loyal to his friends, a natural born fighter and has the courage of his convictions.

It isn’t surprising, then, that Myers was willing to go to extraordinary measures to help secure Hanna’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1897. State legislatures then held the power of appointment to that office, so when Uncle Mark was still a vote short of election, Myers approached William H. Clifford, a black representative from Cuyahoga County, and bluntly paid for his vote in cold, hard cash. “It was politics as played in those days,” Myers later explained to Rhodes. “When I paid Clifford to vote for M.A. I did not think it a dishonest act. I was simply playing the game.”

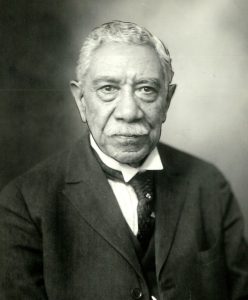

Though McKinley had offered to reward him for his support with a political appointment, Myers was reluctant to neglect his thriving business for an active role in “the game.” The barber showed no reluctance to cash in his political capital for the benefit of fellow African Americans, however. He arranged the appointment of John P. Green, the originator of Labor Day in Ohio, as chief clerk in the Post Office Stamp Division in Washington. This earned Myers the enmity of Harry C. Smith, publisher of the black weekly Cleveland Gazette, who saw the barber’s influence as a threat to his own leadership among the city’ s Negro voters. As the Cleveland Plain Dealer called it in 1900, “George A. Myers is without doubt the most widely known colored man in Cleveland and probably the leading politician of his race in Ohio.”

Among the other appointments for which Myers smoothed the way were those of Blanche K. Bruce as register of the U.S. Treasury and Charles A. Cottrell of Toledo as collector of internal revenue at Honolulu. Only when he saw his livelihood threatened through political action did Myers act in his own interest. In 1902 he asked Hanna “to do me the favor to use every influence at your command” to defeat a proposed state law which sought to place Ohio’s barbering business under the control of a state board. Myers feared that this licensing board, like the barber’s schools, would come under the domination of labor unions which excluded blacks. Hanna promised to “take it up with my friends at Columbus and see if something cannot be done.”

Evidently something could be done, and the bill was defeated.

After Hanna’s death in 1904, Myers dropped his active involvement in politics. “I served Mr. Hanna because I loved him,” Myers told Rhodes, “and even though I put my head in the door of the Ohio Penitentiary to make him U.S. Senator, I would do the same thing again, could the opportunity present itself.” With both Hanna and McKinley gone, however, Myers wasn’t about to stick his neck out for anyone else. Instead, Myers tended to business with impressive results.

By 1920 he had more than thirty employees in his shop, including seventeen barbers, three women’s hairdressers (barriers were falling by then), six manicurists, and two pedicurists. Myers claimed that his was the first barber shop in Cleveland to provide the services of manicurists.

In fact, Myers was on the cutting edge (we wanted to avoid the cliche, but couldn’t resist the pun ) of numerous innovations in the trade. He was one of the first barbers to adopt porcelain fixtures and install individual marble wash basins at each chair. He also pioneered in the use of sterilizers and humidors.

The Koken Barbers’ Supply Company of St. Louis incorporated Myers’ suggestions in the development of the modern barber chair and solicited pictures of Myers and his shop for its house newsletter.

From the standpoint of his busy patrons, perhaps the most appreciated innovation of Myers was the telephone service he provided at each chair. “While having his hair cut a patron may talk to his home or transact business,” marvelled a contemporary trade journal.

“A desk phone is plugged in like a stand lamp and removed when not in use.”

One practice that earned Myers some sharp barbs from Harry Smith was the latter’s allegation that blacks were refused service in the Hollenden barber shop. On the basis of contemporary custom, it was probably true. Another black editor writing on discrimination in Cleveland at the turn of the century described how blacks were told by white barbers to “Go to one of your own people,” only to be told by some of their own, “Now men, we would like to work on you but you know we can’t do it. It would kill our business.” In Myers’ exclusive shop, blacks likely were welcome only behind the barber chairs. To Myers, it probably was simply a case of how that game happened to be played. When Booker T. Washington was organizing the National Negro Business League in 1900, he urged Myers to appear on the program at Boston.

“It is very important that the business of barbering be represented, and there is no one in the country who can do it as well as yourself,” wrote Washington. “We cannot afford to not have you present.”

Nevertheless, Myers demurred. Identifying oneself as “a colored business man,” he once wrote, was tantamount to “an admission of inferiority.” A dozen years later, Washington recommended Myers to head a Republican drive to organize the Negro vote in the presidential election.

Though flattered, Myers turned this offer down too, on account of the press of business. His application to his profession rewarded him well enough.

Myers revealed to Rhodes that he had paid an income tax of $1,617 in 1920, on gross receipts of $67,325. That put him in the upper brackets of Cleveland’s black middle class, where he assumed a position of social as well as business leadership.

Out of a city of close to 400,000 at the turn of the century, Cleveland’s African Americans formed a rudimentary minority of around ten thousand. Though not yet completely ghettoized, they tended to form their own churches, social organizations, and neighborhoods. Myers belonged to the city’s oldest black congregation, St. John’s A.M.E., and was a founding member of the segregated Cuyahoga Lodge of Elks. As a member of the Euchre Club, he belonged to the lighter-skinned social elite of the black community. With other black barbers and service workers, he also formed a Caterers’ Club that became famed for the prestige of its annual banquets.

Yet Myers wasn’t entirely circumscribed by the color line. He was a member of the civic-minded City Club and the Early Settlers Association. According to Cleveland safety director Edwin D. Barry, Myers “had more white friends than any colored man in Cleveland.”

The very proper Victorian parlor of the Myers home on Giddings Avenue was once pictured in the Sunday magazine of the Plain Dealer. Following a divorce from his first wife Sarah, Myers had wed Maude Stewart in 1896. A son from the first marriage and a daughter from the second both became teachers in Cleveland’s public schools.

Despite his father’s activities as a labor organizer, George Myers had become as conservative as any Republican businessman. His own shop was a nonunion one, though his employees seemed content with the arrangement. He was genuinely upset over a May Day riot in the streets of Cleveland, consoling himself with the reflection that “Negroes are neither Socialist, Anarchist nor Bolshevist.”

Although keeping a well-stocked wine cellar for himself, Myers was in favor of Prohibition.

“I favored prohibition for the other fellow — some of my employees–and this is the secret of the Prohibition victory,” he admitted frankly to Rhodes.

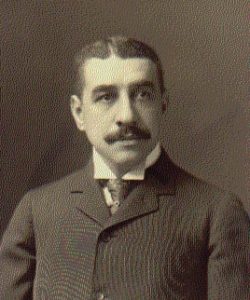

In personal appearance, Myers was always a good advertisement for his tonsorial skills. Trim throughout his life, he displayed a low, full hairline in youth, to which a well-shaped mustache added dignity. A fall down the elevator shaft in a customer’s home once broke his leg and foot, giving him a limp for years and enabling him to forecast the weather afterwards.

Following World War I, Myers purchased a new home in the predominantly Jewish Glenville neighborhood, appropriating the entire third floor for his sanctum sanctorium. Half of it became a billiard room, the other half his library. There he was said to have assembled one of the country’s most comprehensive collections of books by and about African Americans.

It was books that formed the common bond between Myers and James Ford Rhodes. After Rhodes retired from business to write history, Myers would walk over to his Euclid Avenue mansion to give Rhodes his daily shave and trim. On the way, he would often pick up a bundle of books for Rhodes from the library of the Case School of Applied Sciences, then still located downtown. “Me and my partner Jim are writing a history,” he once explained to a curious friend.

“Jim is doing the light work and I am doing the heavy.”

In time Rhodes moved to Massachusetts, where he continued issuing his magisterial “History of the United States From the Compromise of 1850.” As he approached the McKinley volume, Rhodes discovered that Myers might again be of help to him–this time with some of the light work. The historian was primarily interested in the barber’s knowledge of the inside workings of the Hanna McKinley political machine. When the volume was completed, he acknowledged his indebtedness in print “to George A. Myers of Cleveland for useful suggestions.”

Myers and Rhodes covered a wide range of topics in their letters, however, from old Cleveland acquaintances to World War I. When Herbert Croly published his reverential biography of Mark Hanna, Myers complained to Rhodes that he scarcely recognized the subject. “We knew Mr. Hanna to be a rough brusque character with an indomitable will of his own that respected the rights of no one who stood in the way of his successful accomplishment of the object he had set out to accomplish,” he wrote.

World War I proved to be a watershed in the racial thinking of George Myers. After fighting for freedom on the Western Front, Myers predicted to Rhodes that “the Negro will not submit to the atrocities and indignities of the past and present in silence.” Yet Myers was worried about another phenomenon of the war, the Great Migration of Southern blacks to Northern industrial cities. Cleveland’s small, comfortable black minority had suddenly tripled in size, he informed Rhodes. “Many of the Negroes are of the lowest and most shiftless class,” he wrote.

“Where Cleveland was once free from race prejudice, it is now anything but that….”

Prior to the war, Myers had tended to subordinate group solidarity in favor of individual enterprise. He was slow to join the N.A.A.C.P. and the Urban League. Although he supported Booker T. Washington’s efforts at vocational uplift at Tuskegee and was acknowledged by his secretary as “Mr. Washington’s most intimate, personal friend living in Cleveland,” Myers was consistently critical of any support by Washington of separate but equal welfare agencies. He regretted Washington’s endorsement of “in reality a Jim Crow” Y.M.C.A. branch in Cleveland and similarly objected to the formation of the Phillis Wheatley Home for single African American girls.

“Segregation here of any kind to me is a step backward and will ultimately be a blow to our Mixed Public Schools,” wrote Myers to Washington.

Myers preferred to fight racism by private initiative behind the scenes, as when he wrote the editor of the Plain Dealer to protest the paper’s use of the terms “darkies” and “negress.” The practice was halted, though Myers had to repeat his admonition after the war to the paper’s next editor. With less success, Myers also conducted a letter campaign against the screening in Ohio of the Klan-glorifying movie, “The Birth of a Nation.”

But the tensions raised by the Great Migration ultimately caused Myers to adopt a more contentious approach. The clincher probably occurred in 1923, when the Hollenden management informed Myers that his black employees would be replaced with whites effective with his retirement. European immigrants had been challenging the black supremacy in the barbering business since 1908, when James Benson had lost his lease in The Arcade.

In order to save his staff’s jobs, Myers postponed his retirement despite a heart condition brought out by an attack of influenza. A stronger tone entered into his exchanges with the white establishment.

When racial outbreaks loomed over the use of a swimming pool in Woodland Hills Park by Negroes, Myers prevailed on the safety department to station two black policemen there.

He was outspoken in his responses to a 1926 Cleveland Chamber of Commerce survey on immigration and emigration. He placed the blame for the squalid housing conditions in Cleveland’s “black belt” squarely on the Cleveland real estate interests for refusing to rent or sell desirable habitation to colored. Myers also scored the business community in general for its failure to provide economic opportunities for the Negro youth coming out of the schools. “There is not a bank in Cleveland that employs any of our group as a clerk, teller or bookkeeper,” he wrote, “scarcely an office that use any as clerks or stenographers and no stores, though our business runs up in the millions; that employ any as sales-women, salesmen or clerks.”

To Judge George S. Adams, Myers observed that “while I do not condone crime, (all criminals look alike to me), the negro, morally and otherwise, is what the white man has made him, through the denial of justice, imposition and an equal chance.” While the Negro community of Cleveland was working to assimilate the newly arrived immigrants from the South, he told Congressman Chester C. Bolton, “We who formerly lived here before the influx cannot carry the burden alone, nor should we. The industrial interest of the north forced this problem upon us….”

In the late 1920s Myers joined his old rival, Harry Smith of the Gazette, in a public campaign against the establishment of a Negro hospital in Cleveland. In a letter to the Plain Dealer he refuted, on the basis of his own personal experience, charges that blacks were turned away from or refused private rooms at City Hospital. Cleveland was on its way to becoming “one of the greatest medical centers of the world,” Myers asserted, and his people wanted to enjoy, “in common with all others, the benefit of the greatest medical skill and attention that the world has ever known.”

It wasn’t only equal care that Myers was concerned with, but equal opportunity for African Americans in the medical profession. He and Smith also fought for several years to gain admission of colored interns and nurses at City Hospital. City Manager William Hopkins might accuse Myers of having “gone over to Harry Smith bag and baggage,” but City Council finally rewarded their efforts with passage of a resolution granting the desired hospital privileges.

The following morning, January 17, 1930, as his daughter Dorothy drove Myers to his streetcar stop, he told her he was feeling better than he had in a long time. That was good, for at breakfast he had told the family that he faced the most difficult task of his life that day. Unable to continue working any longer, the seventy- year-old barber had finally sold out to the Hollenden. Now he had to inform his employees that they were effectively out of jobs.

He worked all morning, telling the staff just before noon that there would be an important meeting upon his return from lunch. Myers then walked a couple of blocks to the New York Central office in the Union Trust Building to purchase a ticket for a rest cure in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Reaching for his change, he suddenly reeled, grabbed at the counter, and crumpled to the floor.

Even before they could carry him to the building’s dispensary, Myers was dead of heart failure. Once before, after risking his career and reputation to make Mark Hanna a Senator, George A. Myers had withdrawn from “the game” of politics. Now, faced with what would undoubtedly have been the most painful confrontation of his career, he was released by death.

Eulogies poured in from both sides of the color line.

“His death removes a potent factor that those of the race in Cleveland can ill afford to lose at this time,” wrote his old adversary and recent ally, Harry Smith.

City Manager Hopkins estimated his correspondence with eminent men as “good enough and unusual enough to justify its preservation.” That also turned out to be the judgment of history.

ADDITIONAL READING

Russell H. Davis, Black Americans in Cleveland: From George Peake to Carl B. Stokes, 1796-1969 (Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, 1972).

John A. Garraty (ed.), The Barber and the Historian: The Correspondence of George A. Myers and James Ford Rhodes, 1910-1923 (Columbus: The Ohio Historical Society, 1956).

Felix James, “The Civic and Political Activities of George A. Myers, “The Journal of Negro History”, Vol. LVIII, No. 2 (April, 1973), pp. 166-178.

Kenneth L. Kuzmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976).

The George A. Myers Papers (Columbus: Ohio Historical Society Archives)

This article first ran in Timeline Magazine, Jan/Feb 2000.

John Patterson Green, father of Labor Day in Ohio, and his enduring legacy -Cleveland.com Sept 1, 2014

Here is link to Rep. Green’s autobiography, “Fact Stranger Than Fiction”

Black Lynching in the Promised Land: Mob Violence in Ohio 1876-1916 by Marilyn K. Howard

The link is here

If that does not work, try this

The purpose of this study is threefold. First, I wanted to tell the story of a long forgotten part of Ohio’s history–the lynching of black men by white mobs. Second, I wanted to ascertain if the theory developed by historian Roberta Senechal de la Roche was correct: that the components of a lynching could be broken down and labeled, and that by doing so, it could be predicted whether a lynching was going to occur. The latter part of the aforementioned statement is important, for lynching is a premeditated crime. If the components of a particular lynching are known, perhaps that lynching can be averted. Third, I wanted to verify if the passage of the anti-lynching law of 1896–the so-called “Smith law,” named after Harry C. Smith, a black newspaper owner and Republican state legislator from Cleveland, Ohio–was the reason that lynchings of black men tapered off and ceased altogether after 1916. Finally, I wanted to see if there was a definitive reason for which black men were lynched, be it sexual, economic, or racial.

Accordingly, I examined twelve lynchings and thirteen incidents in which lynchings were averted. I also looked at a legal execution–the victim had nearly been lynched before his execution by the state could be carried out–and an incident in which a lynching was reported but found to be the hanging of an iron statue made in the likeness of a black man.

de la Roche’s theory turned out to be correct. In each of the twenty-three incidents, at least two of her four variables were present. Second, it was impossible to ascertain with any certainty if the Smith law was responsible for the decline and eventual demise of the lynchings of black men in Ohio. In fact, three men were lynched after the Smith law was passed. Third, there is no definitive reason for why black men were lynched in Ohio, although accusations of sexual assault played a powerful role. Four of the men who were lynched had been accused of or charged with murder, five had been charged with sexual assault, one had been charged with assault, one had been charged with a murder and an assault, and one with robbery. Of the ten men who escaped being lynched, five had been accused of sexual assault, three had been accused of assault, and the last man was a white county sheriff who was nearly lynched for protecting a black man accused of sexual assault.

There was a common thread running through all but one of the incidents: The men who were lynched or escaped being lynched were all black, and except in one case, the mobs were white. Clearly mob in Ohio contained a strong racial element, although it could not be verified with any great certainty if it was the sole motive in any of the incidents.

THE BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENT AND COMMUNITY PLANNING IN URBAN PARKS IN CLEVELAND, OHIO, 1945-1977

BY STEPHANIE L. SEAWELL

Univ of IL 2014

The link is here

If that link does not work, try this

Lecture delivered in 1983 by Kenneth Kusmer from Temple University. Part of the Cleveland Heritage Program

John O. Holly 1935 Cleveland Public Library

Cleveland’s Original Black Leader: John O. Holly

By Mansfield Frazier

In 1903, the year John O. Holly was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, we were a nation of 80.6 million people; a first class postage stamp cost two cents; Henry Ford organized the Ford Motor Company; the Wright Brothers made their historic first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina; and Teddy Roosevelt was president.

In 1935, at age 32, Holly would become the driving force in establishing the Future Outlook League, which grew to become one of the most powerful organizations in Cleveland demanding — and achieving — better economic treatment for blacks. It was a long and rocky road he had to travel to win victories in the end, but the hallmark of his journey was his tenacious perseverance and determination. When something got in his way he found a way around, over, or though it. He had a tremendous sense of vision, and better yet, the ability to transmit what he could envision to others. If there is such a thing as a natural born leader, John O. Holly fit that description to a “T.”

But nothing came easy for Holly, especially early in his life. When his family moved to Rhoda, Virginia, at age 15 he quit school to work in the coal mines doing hard, dangerous and dirty work. It’s doubtful that the memory of those dark and dank coalmines ever left him, and perhaps inspired him in later years.

World War I was just concluding in Europe and black soldiers, as they had in all of our nation’s previous armed conflicts going back to the Revolutionary War, had served bravely … only to be treated as second-class citizens upon their return to the United States. The lack of prejudice black American soldiers experienced in Europe would later set the stage for the call for better treatment at home, and Holly would become one of the men who would call the loudest and longest.

Holly’s family would move soon again, this time to Roanoke, Virginia where he returned to school and graduated from Roanoke Harrison High School. After the family moved to Detroit, he began working in his father’s trucking business while attending the Cass Technical Commercial School. Holly’s father, in addition to running his own business, was involved in organizing autoworkers, which must have made a great impression on him as a young man and no doubt was instrumental in determining the path Holly’s life would take in later years.

In 1926, Holly met and fell in love with Leola Lee. He married her and moved to Cleveland, the city in which she was raised. They had two sons, Arthur and Marvin. Holly initially found work in Cleveland as a porter at Halle Brothers Co., the most elegant department store in Cleveland. After being laid off from that job, he found employment as a clerk at the Federal Sanitation Company, a chemical manufacturing company, and then later as a chauffeur.

When Holly drove his employer to Chicago for the 1933 World’s Fair, where, according to the definitive book on Holly and his era, Alabama North, written by Kimberly L. Phillips, “he witnessed blacks with jobs and managerial positions that had been won through boycotts against while-owned stores.” Phillips further writes, “Holly must have heard the excited buzz that fourteen inexperienced black employees hired at the South Center Department Store had multiplied to become 60 percent of the 185 employees.”

Upon returning to Cleveland Holly excitedly recruited M. Milton Lewis, a college-educated black who could only find work selling insurance, and Harvey Johnson, who had a law degree from Western Reserve Law School, but was excluded from employment at white law firms. He held a meeting at his home to form the Future Outlook League (FOL) in 1935, with Holly serving as president, Lewis as vice-president, and Johnson as legal counsel.

From the very beginning, Holly’s insistence on direct, in-your-face action in the streets repelled the black middle class while drawing in the working class and those in need of employment. He was castigated as an “outsider” and a “foreigner” by the successful blacks that were more accustomed to negotiations and patience in their dealings with whites.

Despite his short stature, dark skin, and his pronounced southern accent (which many in the black middle class ridiculed, and former Cleveland Mayor Carl B. Stokes unfortunately referenced in somewhat uncharitable terms in his book Promises of Power) he was embraced by the black unemployed that found his presence and urgency appealing. But there was precedence.

A few years after arriving in New York City, Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican by birth, had launched the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). By mid-1919, the organization had grown to over two million members with the simple message that blacks should own their own businesses. The reason for the explosive membership of his organization was simple: The NAACP, which had been formed in 1909, was comprised of whites and lighter-skinned blacks. Rumors persisted that if a black wasn’t as light-skinned as a brown paper bag they couldn’t gain entrance into the organization. This left out the vast majority of blacks, who eagerly joined Garvey’s organization. When Holly’s organization, which was built from the grassroots up came along, the thousands of blacks that felt excluded by the elitist NAACP had found a home.

Nonetheless, there still was widespread disinterest in the FOL in Cleveland by the established black power structure until William O. Walker, who had recently purchased the Call & Post, endorsed Holly’s efforts. It would prove to be a powerful endorsement that worked both ways. Eventually white businesses began to advertise in Walker’s publication, which Holly adroitly used to lambast older and more cautious leaders as “moss back reactionaries.”

* * *

The earliest “Don’t Buy” boycott appeared in Chicago in the late twenties. Black men who had served in uniform for their country were embittered and emboldened. They reasoned that if they had been good enough to fight and die, why weren’t they good enough to be hired, especially in their own neighborhoods? The first target was a small chain of grocery stores in Chicago’s black ghetto that refused to employ persons of color. Referred to as “Spend Your Money Where You Can Work,” this first campaign sparked a larger boycott against the Woolworth stores (which, at the time was one of the country’s largest national chains).

The Woolworth’s that refused to hire blacks was located in the middle of Chicago’s “Black Belt.” An aggressive black newspaper, the Chicago Whip, published fiery editorials endorsing the campaign. News of Chicago’s successful boycott sparked similar campaigns across the country, particularly in New York between 1932 and 1941.

The black press, which largely had been — and to some degree still is — ignored by the white mainstream media throughout much of our nation’s history would play a pivotal role in spreading the word about the boycotts and other battles confronting the black community nationwide. Newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, The Chicago Defender, the Baltimore Afro-American, the Amsterdam News and Cleveland’s Call & Post constantly agitated on the issue of jobs for blacks in their own communities. Robert Lee Vann, the Courier’s dynamic editor supposedly even brought the issue up at the White House in the spring of 1941.

As Call & Post publisher Walker occasionally recounted, about a dozen black newspaper publishers were summoned to the White House by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as America was about to enter World War II. Many of the papers had been publishing editorials questioning why blacks should join the military for service in yet another foreign war, after being treated so shabbily upon returning home from World War I.

President Roosevelt allegedly made both threats and promises at the meeting. He told the publishers that as long as the U.S. was not in a state of war, they could write and publish whatever they wanted. But he cautioned them that once a state of war existed, to editorialize against it constituted sedition, a crime for which he would have them arrested and imprisoned.

But Roosevelt knew they had a valid point and made them a promise. Don’t argue against the war effort and he would integrate the military after the conclusion of the conflict. They agreed, and while Roosevelt wasn’t alive to keep his word, his successor, President Harry Truman, did make good on the promise.

Walker said that before the meeting was over, Vann brought up the issue to the president about blacks not being able to get jobs in their own communities. Roosevelt said that while it wasn’t a federal issue, he would see what he could do to help the situation. It was Walker’s belief that Roosevelt was only interested in getting them out of the Oval Office as quickly as possible, and he never lifted a finger to help on the jobs issue.

With or without the president’s help, the issue was gaining momentum around the country. Following Chicago’s example, blacks in Brooklyn and Harlem instituted “Don’t Buy” campaigns against various local white stores. Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., one of the most powerful black men in the U.S., was extremely aggressive on the issue and helped to place blacks in Harlem in hundreds of white-collar jobs.

This was during the height of the Depression and many folks, including whites, were out of work. Unionism was on the rise, and so was Communism. The FOL made strategic alliances with any groups that could help them advance their cause, and they did something the old-line black organizations had been reluctant to do: They put women in leadership roles, which was unprecedented.

Women like Marge Robinson and Isabelle Shaw were members of the “Investigation Committee,” which, again according to Phillips, “examined store practices and met with owners.” Most of the owners were reluctant to change their hiring practices. Holley resorted to picketing, which eventually yielded results.

According to Phillips, “Over the second half of the 1930s thousands of employed and unemployed African Americans, many of them migrants, were schooled in independent radical activism under the aegis of the league’s boycotts and meetings.” But jobs were not all that Holly was after. He wrote to a friend: “These men and women who are being placed in various stores will take the places of the white man and be the merchants of tomorrow with the experience acquired under the white man’s instruction.” He clearly wanted business ownership, similar to Garvey.

Saturday was the busiest shopping day of the week and when blacks showed up at the Woodland Market at 55th Street and Woodland with their signs that read “Fools Trade Where They Can’t Work” enough shoppers turned away to cause storeowners to begin rethinking their hiring policies. In some cases, blacks were hired within days, in others it would take weeks or more of picketing.

Other store owners, like white southerner Frank Barnes (who owned a store on East 73rd and Kinsman Avenue), remained recalcitrant and went to court to obtain an injunction that stopped the picketing. But Holly and his followers went door-to-door with leaflets and eventually drove Barnes Grocery Store out of business.

Holly and the other leaders of the FOL sometimes faced tear gas, and at other times were arrested. Yet they persevered and eventually persuaded storeowners to hire blacks in decent numbers. When blacks got hired they joined the FOL and became exceptionally loyal to the organization. The membership roles began to grow to the point where the established black leadership could no longer ignore Holly and the FOL. It was turning into a potent force, one to be reckoned with. And then Holly turned the attention of the organization towards downtown,

I clearly recall a 1947 protest at The May Co. a department store that was located in downtown Cleveland, which still refused to hire black sales clerks. Picket lines formed in front of the store — black folks carrying signs that read, “Don’t Shop Where You Can’t Work.” My mother was carrying one of the signs as I stood across Euclid Avenue with my father.

He was one of the dozen or so black men — bar owners, numbers runners, professional boxers — standing silently across the street from the protest (a few with pistols in their pockets) observing. Others also brought their children along to watch history unfold. I was four years old at the time.

The white police officers glowered at the knot of black men, and the black men glowered right back. I recall Holly and another man crossing the street to briefly huddle with the black men and then walking over and speaking with the police officers before going back to talk to the demonstrators. The term “shuttle diplomacy” had yet to be invented, but Holly had already mastered it. In short order, May Co. officials agreed to hire three black sales clerks. It wasn’t long after pickets appeared that Ohio Bell followed suit and hired Artha Woods (who went on to serve on the Cleveland City Council, and later as clerk of that body) as its first black female telephone operator in Cleveland.

The next month, I was among the first group of black kids to ride the merry-go-round at the previously segregated Euclid Beach Park. In 1946, City Councilman Charles V. Carr had introduced an ordinance to make it illegal for amusement park operators to discriminate. And, by the summer of ’47 (after some protests had turned violent) that battle was also won and the park was integrated.

Just as Birmingham, Ala., is known as the birthplace of the black civil rights movement, Cleveland can rightly claim to be the birthplace of the black economic and political rights movement in this country in large part due to the efforts of Holly, Carr and their associates.

When “downtown” success finally came, the FOL didn’t rest on its accomplishments. They forged ahead and expanded their efforts to include factories and other businesses where blacks had been historically underrepresented, and strengthened alliances with unions.

Holly was an acknowledged master at organizing. Active in the Democratic Party he took on Herman Finkle for the City Council seat in Ward 12 in 1937, which at the time encompassed much of the Central neighborhood. Although he lost, his zeal and skills caught the attention of Democrats statewide. He founded the statewide Federation of County Democrats of Ohio, Inc.

Carl Stokes, the first black mayor of a major American city, (in addition to the unkind remarks mentioned earlier), paid great homage to Holly in his autobiography. He wrote, “… when I was twenty-one, I had the privilege of learning about the realities of politics from John O. Holly.”

Stokes went on to say that Holly was among the most remarkable men he’d ever known, and that as a child growing up in the projects on 40th Street near Quincy Avenue, like so many others in the community, he came to revere the man as a hero.

“We didn’t call it black pride back then,” writes Stokes, “but if there was ever black consciousness and pride in Cleveland, it came though John O. Holly. He came along at a time when Negroes lacked any leadership from within. And to be black-complexioned even minimized your mobility within the ghetto.” But nothing stopped Holly.

Unlike many other so-called black leaders of that era — and to some extent even today — Holly took men like Carl Stokes under his wing and schooled them in the art of politics, thus preparing a new generation of leaders. Stokes readily admitted that without this tutelage he probably would never have become the nation’s first black mayor.

Holly died in December of 1974 at age 71 at Richmond General Hospital, leaving behind his second wife Marguerite; He was interred in Highland Park Cemetery. Cleveland’s main post office at 30th and Orange Avenue is named for John O. Holly, Cleveland’s original black leader.

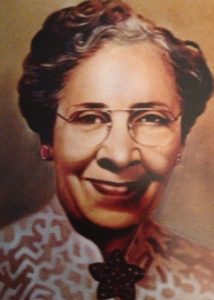

Jane Edna Hunter, Lethia C. Fleming,

Hazel Mountain Walker, L. Pearl Mitchell

Four “Influential Race Women” and their Community

By Marian Morton

In 1939, these “influential race women” were applauded for “their service to the Negro race and its progress”1: Jane Edna Hunter, Lethia C. Fleming, Hazel Mountain Walker, and L. Pearl Mitchell. These ambitious, accomplished women – a social worker, a Republican activist, an educator and actress, and an officer in a local and national civil rights organization – pursued racial progress through institutions and organizations, some black and some racially integrated; through local and national politics, in schools and on stages, through accommodation and confrontation.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Cleveland’s small black population of 5,988 lived in almost all neighborhoods of the city although many blacks lived on the East side. Most remained closer to the bottom than to the top of the economic ladder, but some made small fortunes, and others earned middle-class incomes. By 1930, however, the city’s black population had soared to 71,899,2 swelled by newcomers from the South, fleeing disenfranchisement, rural poverty, and racial segregation enforced by law and by violence. The sheer numbers of this first great migration eroded Cleveland’s “tradition of racial fairness.”3 Clearly defined black neighborhoods developed – most notably the Central area – as blacks were forced, or chose, to live close to one another. Informal exclusion from public and private facilities followed. Compared to other ethnic groups, the economic opportunities of African Americans diminished. Considered unsuited to industry because of their rural background, they were also often excluded from the skilled trades by unions.4

Hunter, Fleming, Walker, and Mitchell watched this enormous influx with dismay and concern. Middle-class by virtue of their education and financial security, these women felt an obligation to help those less fortunate than themselves. The task was enormous: to remedy the history of involuntary servitude in the South and racial prejudice nation-wide, worsened by the trauma of uprooting, the newness of urban life, and growing racial discrimination. Each woman approached this task differently.

“No race of people will do more for you than you are willing to do for yourselves,“5 announced Jane Edna Hunter at a dinner in her honor at the Phillis Wheatley Association (PWA) she had founded two decades earlier. Hunter’s philosophy of black self-help – with significant financial aid from whites – was borrowed from Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute and the country’s most prominent spokesman for African Americans in the late nineteenth century. Hunter’s autobiography, A Nickel and a Dime, published in 1940, was modeled closely on Washington’s Up from Slavery; both books told the story of the author’s rise from poverty to success with the help of generous white people. Hunter emphasized her own difficulties as an African American woman, recounting her efforts to fend off unwanted advances from men when she worked as a chambermaid and describing the

1

sexual perils she faced when she arrived in the big city of Cleveland. The PWA was intended to address those problems, providing safe, respectable shelter and job training for young African American women.

Hunter, born in 1882 in South Carolina, arrived in Cleveland in 1905, looking for work as a nurse; she had trained at Hampton Institute, a vocational school modeled after Tuskegee. Six years later, she established the Working Girls Association, a boarding home for young, single black women, similar to the whites-only YWCA. The home was renamed the Phillis Wheatley Association after an African American poet, and in 1927, the association moved into an imposing building, designed by the architectural firm of Hubbel and Benes (also the designers for the Cleveland Museum of Art) on Cedar Road in the heart of the Central neighborhood. Hunter cultivated powerful white allies and patrons including Henry A. Sherwin, founder of the Sherwin Williams Company; Elizabeth Scofield, a trustee of both the PWA and YWCA; and soon-to-be congressman, Republican Frances P. Bolton.

Although the PWA flourished, providing classes, clubs and social activities as well as room and board for dozens of young women, Hunter had her critics in the black community. They charged that the PWA endorsed the principle of racial segregation, was controlled by the wealthy whites on its board of trustees, and specialized in training young black women as domestic servants for white families. To those critics, Hunter responded pragmatically: where else would she get the money to maintain an institution that did so much good for her clients? And what other jobs were available to them? Most of Hunter’s black critics eventually came around.

Hunter also had her enemies. Chief among them was African American entrepreneur, Albert D. Boyd, also known as “Starlight,” described by Hunter as the “procurer for wild, wealthy men; later master of the underworld; and finally, manipulator of the Negro vote for unprincipled politicians.”6 Hunter accused Starlight of being a pimp whose saloons and brothels kept the Central neighborhood – also known as “the Roaring Third”– a center of vice and crime. His accomplice, Hunter claimed, was “Timothy Flagman,” whom her readers recognized as Thomas W. Fleming, the first black elected to Cleveland City Council. Hunter mounted a futile campaign to defeat Fleming in 1919.

Out of necessity or conviction, Hunter cultivated good relationships with the white community. But like her role model Washington, she was not uncritical of the racial status quo. In her autobiography, Hunter pointed out the hypocrisy of whites “from society’s leading families” who encouraged vice in the Roaring Third by patronizing its clubs and dives but who barred blacks from their own “respectable white neighborhoods.”7 She also maintained that separate facilities, such as schools, must be equal: “I am … fully convinced that we cannot make real advancement in our pursuit of education … until Boards of Education provide equal educational facilities under the law.”8 Equal, if separate, would also be the position of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for another decade.

6 Jane Edna Hunter, A Nickel and A Dime: The Autobiography of Jane Edna Hunter, edited by Rhondda Robinson Thomas (Morgantown, W. Va., West Virginia University Press, 2011), 70.

7 Hunter, 112.

8 Hunter, 153.

2

Like Washington, Hunter achieved enormous popular acclaim – with honorary degrees from half a dozen colleges – but at some cost to herself. A candid admirer described her in 1939: “Friend and foe alike admit/ There’s only one Jane/ Peerless in her realm, to wit/ a gem so rare. They say/ ‘We’ll never see her like again.’”9

In the post-World War II era when dreams of racial integration revived, the racial separatism and accommodationism that Hunter had successfully used to promote her cause, and herself, had become outdated. In 1947, she was forced to retire at age 65 by the Cleveland Welfare Federation, which, as a funder of the PWA, had some control over its direction.

Hunter died in 1971. The Phillis Wheatley Association today provides inexpensive housing and programs for children and the elderly.

Despite Hunter’s open animosity to her husband Thomas W. Fleming, Lethia C. Fleming was a charter member of the PWA and in 1933 organized a dinner honoring Hunter. Perhaps Fleming realized that the PWA was a force for good in her own neighborhood; she lived around the corner on E. 40th St. Or perhaps her long career in politics allowed her to overlook personal slights or philosophical disagreements. Like her husband, she believed that politics were the avenue to success for black people.

Like Hunter, Fleming was a southerner, born in Virginia in 1876 and educated at Morristown College in Morristown, Tennessee. She came to Cleveland in 1912 after her marriage. In 1914, Fleming was one of the few black women to march down the streets of Cleveland in the parade of 10,000 male and female supporters of votes for women. Like most blacks of the first decades of the twentieth century who remembered that the party of Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves, she was a Republican. Republicans had also elected Clevelander John P. Green to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1881 and in 1892, to the Ohio Senate, its first black member. And Republicans had sent George A. Myers, a powerhouse in Cleveland’s black community, to its national convention in 1892, 1896, and 1900.

Fleming staunchly stood by her husband at his trial for bribery in 1929, testifying on his behalf, and after his indictment, she unsuccessfully asked Ohio Governor George White to pardon him. “A power among the women voters of the Third District and a Republican party leader of recognized ability,”10 she was briefly considered for his vacant seat in City Council. (Clevelanders did not elect an African American woman to City Council until 1949 when Jean Murrell Capers was chosen.)

The concentration of African Americans on Cleveland’s East side – in the ghettos created by the first great migration and racial discrimination – made possible the election of other black councilmen who gained patronage and political clout. Their early victories included the integration of the staff at Cleveland City Hospital.11 In 1934, the three African American councilmen persuaded their white colleagues to pass a resolution condemning the exclusion of blacks from the restaurant in the U.S. Capitol.12

Republican political boss Maurice Maschke, a patron of both Boyd and Fleming, assiduously cultivated the black vote, making public appearances at the PWA and other black

9 Lethia C. Fleming, MSS 3625, container 1, folder 1. 10 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 11, 1929: 6.

11 Kusmer, 273.

12 Cleveland Call and Post, December 8, 1934: 1.

3

institutions. When he died in 1936, the Cleveland Call and Post gave him credit for “getting the Negroes’ feet placed on the first step of the political ladder.”13

Fleming remained active in Republican women’s organizations and managed the local campaigns for Republican presidential candidates in 1928 and 1936. She stayed loyal to the Republican Party long after most blacks switched their political allegiance to the Democrats during the New Deal. In 1953, she was the only black on the nominating committee of the Republican National Committee.

Described as a “tall woman [of] striking appearance,”14 Fleming was a frequent speaker at civic events, popular with all audiences, white and black, male and female. She supported organizations specifically aimed at blacks: the PWA, the Home for Aged Colored People, and the Negro Welfare League, later the Urban League, which had ties to Washington. But she also belonged to the NAACP, one of whose founders was Washington’s rival, W.E.B. DuBois, which was dedicated first and foremost to racial integration.

Fleming worked for the Division of Child Welfare of Cuyahoga County for twenty years and retired in 1951. Ever the politician, she gave this testimony at her retirement: “I will never forget the loving cooperation in which the two races have worked together in this city.”15 Fleming died in 1963.

Hazel Mountain Walker was less diplomatic than Fleming. When asked in 1954 about the school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education, then pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, Walker responded: “Abolishing separate schools without abolishing slums and ghettos will not usher in the millennium. We have no Jim Crow schools in Cleveland, but still this school [George Washington Carver Elementary School, where she was principal], and other schools in the Central Area are nearly 90 percent colored because the residents of the area are more colored than white.”16 Walker made her contribution to her race as an educator, an actress, and an activist for racial integration.

Born in Ohio in 1883, Walker received a bachelor’s degree and in 1909 a master’s degree from Western Reserve University; she also graduated with honors from Cleveland School of Law in 1919 but never practiced law. She became the first black principal in the Cleveland public school system in 1936 and the first to rise directly from the classroom to the principal’s office.

She began her teaching career at Mayflower Elementary School in 1909, earning $45 a month 17 and retired in 1958 as principal of George Washington Carver Elementary School.

That was a challenging half-century for Cleveland public schools. In its crowded classrooms, black children from the American South sat next to the white children of Irish, German, Russian, Italian, and Jewish immigrants. Public school teachers and administrators had to teach all of them how to read, write, add, subtract, and live together. Living together remained Walker’s goal throughout her life.

Walker combined the roles of teacher and actress. She was an early member of the Gilpin Players, a theater group initiated in 1920 and sponsored by Karamu House. Founded in

4

1915 as the Playhouse Settlement, Karamu was the creation of Russell and Rowena Jelliffe, who believed that interracial theater would bring interracial understanding. Walker is credited with giving Karamu its name, which in Swahili means “place of joyful meeting.”

She performed at Karamu for more than two decades in plays that revolved around racial themes and plays that did not, in plays that featured Negro dialect and in classical drama. She got rave reviews from the Cleveland Plain Dealer for her performances in Nan Bagby Stephens’ “Roseanne,” a 1930 play by and about blacks, and as the cigarette-smoking Maria in “Porgy,” the play upon which the musical “Porgy and Bess” was based.18 In a 1935 production of “The Soon Bright Day,” Walker’s were the opening lines: “Mornin’ Jesus, and thank yuh Suh for this soon bright day.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer exclaimed that she was “better than she has ever been.” 19

In 1951, in a performance commemorating the 100th anniversary of a woman’s rights convention in Akron, Walker recreated the dramatic speech of the former slave Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I A Woman?”20 The question was directed to the hostile minister in the audience who maintained that women couldn’t have equal rights because they were weaker than men, to which Truth famously replied: “Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman?” Walker also performed in Ibsen’s “Ghosts” in 1951 and in 1954 starred in “Member of the Wedding” as Berenice, the cook, counselor, and confidante to the family’s children.

Karamu highlighted the abilities of blacks in a city that had trouble believing in them, and Walker’s performances on Karamu’s stage underscored her own belief that blacks and whites could succeed together.

Walker also pursued interracial progress through politics. She remained active in Republican politics at least through the 1930s. So active in fact that the Cleveland Citizens League complained to the Cleveland School Board in 1932 about her “political activities” while she was teaching at Mayflower Elementary School. 21 The complaints apparently went unheard; Walker continued as precinct leader in the city’s 11th Ward and only three years later, got her path-breaking appointment as principal of Rutherford B. Hayes Elementary School. In 1943, she and L. Pearl Mitchell, “two of Cleveland’s most prominent Negro women,” were appointed to the Cleveland Womanpower Committee, designed to recruit women into war-time industries; “Both women are expected to bring into full focus the problem of integrating Negro women into the city’s many war plants, where, with few exceptions, they have not previously been welcomed.”22

Cleveland’s booming industries during World War II created jobs for a second great migration of blacks to the city. And in the post-war period, Cleveland’s spirit of racial openness revived. City Council, conscious of new black voters, set up a Community Relations Board in 1945 and in 1950 passed fair employment practices legislation.

5

Walker remained a public advocate for equal opportunity, frequently speaking at conferences and other civic events. She was honored by Karamu for her long years of service and by the Urban League Guild for her work in public education. By the time of her death in 1980, she had become a symbol of African American success in Cleveland, often cited as proof of black capabilities and/or the city’s racial liberalism.

Although she and Walker often worked together, L. Pearl Mitchell was the more vocal critic of Cleveland’s racial status quo, reflecting the growing strength of the city’s black community during the 1930s and 1940s. Known as “Miss NAACP,” she led the charge for racial integration of the city’s public institutions.

Mitchell was born in 1883. Her father, Samuel J. Mitchell, was president of historically black Wilberforce College in Wilberforce, Ohio. She had roots in Cleveland. Her grandfather escaped slavery and settled in Cleveland; her father grew up in Cleveland before attending Wilberforce himself.

Her first public appearances were with the Gilpin Players at Karamu. In 1930, she was vice-president of the group, and Walker was president; both were in the cast of “Porgy” in 1933. Mitchell’s most noteworthy role, however, was in Jo Sinclair’s “The Long Moment,” which opened in 1950 at the Cleveland Playhouse. The plot revolved around a young black musician who was trying to “pass” as white; Mitchell, light-skinned herself, played his mother. The show got good reviews, but more important, it was the first show at the Playhouse with an interracial cast.

Mitchell worked for two decades at the Juvenile Court until the mid-1940s. Her real vocation, however, was the NAACP. Founded in 1909 by blacks and whites, its goal was the racial integration of all aspects of American life. The Cleveland chapter was established in 1914. During the 1920s it successfully challenged the exclusionary policies of stores, theaters, and public facilities and residential segregation in the new suburbs.

Mitchell’s main target was the public school system. In 1932, Mitchell, then vice- president of the Cleveland NAACP, filed a report with the Cleveland school board maintaining that the school district deliberately created racial segregation: forcing black children to attend Central High School when it was not in their neighborhood, discouraging black girls from attending Jane Addams School and black boys from the Cleveland Trade School, and assigning black teachers to black-only schools.23 In 1939, Mitchell argued that the new Central High School should be built east of E. 55th so that its student body would be more “cosmopolitan” – not entirely black. Hunter publicly disagreed24 and won the argument when the school was built on E. 40th, not far from the PWA in the predominantly black Central neighborhood.

In 1935, Mitchell complained that two new public housing projects would foster racial segregation because one project was designated for blacks and one for whites.25 (In 1961, Mitchell pointed out that all public housing projects had become black “ghettos.”26) In 1946, the NAACP opposed the building of Forest City Hospital in the Glenville neighborhood, intended to be a place where black doctors could practice, on the grounds that it would reinforce the

23 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 8, 1932: 4.

6

racial segregation of existing hospitals. The hospital opened in 1957, its staff and patients became predominantly African American, and it closed in 1978.

Mitchell helped to end the racial segregation of children in the Ohio’s Sailors and Soldiers Orphan Home in Xenia, Ohio. As a member of its board of trustees, she took her case to the public and to state officials in 1958. Echoing the 1954 Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board, which mandated the desegregation of the country’s public school, Mitchell maintained: “It is difficult .. to understand what segregation and separation mean to human souls when you have never experienced it.”27

Mitchell’s other cause was Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, a social service organization founded in 1908 at Howard University. In 1964, Mitchell persuaded the sorority to donate $440,000 to the NAACP. 28 With federal money and initial guidance from Mitchell, the sorority in 1965 established the Women’s Job Corps Center in Cleveland, intending – as had Jane Edna Hunter 60 years earlier – to provide vocational training for women.

When Mitchell died in 1974, memories of her fierce confrontations with public officials had faded. The Cleveland Plain Dealer described her: “a soft-spoken but courageous, determined leader for social equality for minorities and the poor.”29

All four lived to see the civil rights movement gain strength through the 1950s and early 1960s under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; they probably heard him speak because he came to Cleveland often. All but Fleming saw the 1967 election of Carl Stokes, the first African American mayor of a big city. In 1976, federal Judge Frank J. Battisti, responding to a brief brought by the NAACP, validated Mitchell’s claim made more than 40 years earlier that the Cleveland School Board intentionally maintained racial segregation in the city’s public schools; he ordered the desegregation of the schools by busing students. Walker lamented that Cleveland’s residential segregation made busing necessary.30

For most of the twentieth century and for most of their lives, Jane Edna Hunter, Lethia C. Fleming, Hazel Mountain Walker, and L. Pearl Mitchell fought the deeply rooted racial inequities of Cleveland. They didn’t win all their battles. But these four “influential race women” did help to create new institutions and organizations and skillfully employed old ones; they enlisted the support of whites and blacks, and perhaps most important, they challenged public officials and private consciences.

7

Written by Kenneth L. Kusmer

AFRICAN AMERICANS. Cleveland’s African American community is almost as old as the city itself. GEORGE PEAKE, the first black settler, arrived in 1809 and by 1860 there were 799 blacks living in a growing community of over 43,000. As early as the 1850s, most of Cleveland’s African American population lived on the east side. But black and white families were usually interspersed; until the beginning of the 20th century, nothing resembling a black ghetto existed in the city. Throughout most of the 19th century, the social and economic status of African Americans in Cleveland was superior to that in other northern communities. By the late 1840s, the public schools were integrated and segregation in theaters, restaurants, and hotels was infrequent. Interracial violence seldom occurred. Black Clevelanders suffered less occupational discrimination than elsewhere. Although many were forced to work as unskilled laborers or domestic servants, almost one third were skilled workers, and a significant number accumulated substantial wealth. Alfred Greenbrier became widely known for raising horses and cattle, and MADISON TILLEY employed 100 men in his excavating business. JOHN BROWN, a barber, became the city’s wealthiest Negro through investment in real estate, valued at $40,000 at his death in 1869. Founded by New Englanders who favored reform, Cleveland was a center of abolitionism before the CIVIL WAR, and the city’s white leadership remained sympathetic to civil rights during the decade following the war. Black leaders were not complacent, however. Individuals such as Brown and JOHN MALVIN often assisted escaped slaves, and by the end of the Civil War a number of black Clevelanders had served in BLACK MILITARY UNITS in the Union Army. African American leaders fought for integration rather than the development of separate black institutions in the 19th century. The city’s first permanent African American newspaper, the CLEVELAND GAZETTE, did not appear until 1883. Even local black churches developed more slowly than elsewhere. ST. JOHN’S AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL (AME) CHURCH was founded in 1830, but it was not until 1864 that a second black church, MT. ZION CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH, came into existence.

Between 1890-1915, the beginnings of mass migration from the South increased Cleveland’s black population substantially (seeIMMIGRATION AND MIGRATION). By World War I, about 10,000 blacks lived in the city. Most of these newcomers settled in the Central Ave. district between the CUYAHOGA RIVER and E. 40th St. At this time, the lower Central area also housed many poor immigrant Italians and Jews (see JEWS & JUDAISM). Nevertheless, the African American population became much, more concentrated. In other ways, too, conditions deteriorated for black Clevelanders. Although black students were not segregated in separate public schools or classrooms (seeCLEVELAND PUBLIC SCHOOLS), as they often were in other cities, exclusion of blacks from restaurants and theaters became commonplace, and by 1915 the city’s YOUNG WOMEN’S CHRISTIAN ASSN. (YWCA) prohibited African American membership.HOSPITALS & HEALTH PLANNING excluded black doctors and segregated black patients in separate wards. The most serious discrimination occurred in the economic arena. Between 1870-1915, Cleveland became a major manufacturing center, but few blacks were able to participate in INDUSTRY. Blacks were not hired to work in the steel mills and foundries that became the mainstay of the city’s economy. The prejudice of employers was often matched by that of trade unions (see LABOR), which usually excluded African Americans. As a result, by 1910 only about 10% of local black men worked in skilled trades, while the number of service employees doubled.

Increasing discrimination forced black Clevelanders upon their own resources. The growth of black churches was the clearest example (seeRELIGION). Three new churches were founded between 1865-90, a dozen more during the next 25 years. Baptists increased most rapidly, and by 1915 ANTIOCH BAPTIST CHURCH had emerged as the largest black church in the city. Black fraternal orders also multiplied, and in 1896 the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People was established (see ELIZA BRYANT VILLAGE). With assistance from white philanthropists (see PHILANTHROPY), JANE EDNA HUNTER established the PHILLIS WHEATLEY ASSOCIATION, a residential, job-training, and recreation center for black girls, in 1911. Blacks gained the right to vote in Ohio in 1870, and until the 1930s they usually voted Republican. The first black Clevelander to hold political office was JOHN PATTERSON GREEN, elected justice of the peace in 1873. He served in the state legislature in the 1880s and in 1891 became the first African American in the North to be elected to the state senate. After 1900 increasing racial prejudice made it difficult for blacks to win election to the state legislature, and a new group of black politicians began to build a political base in the Central Ave. area. In 1915 THOMAS W. FLEMING became the first African American to win election toCLEVELAND CITY COUNCIL.

The period from 1915-30 was one of both adversity and progress for black Clevelanders. Industrial demands and a decline in immigration from abroad during World War I created an opportunity for black labor, and hundreds of thousands of black migrants came north after 1916. By 1930 there were 72,000, African Americans in Cleveland. The Central Ave. ghetto consolidated and expanded eastward, as whites moved to outlying sections of the city and rural areas that would later become SUBURBS. Increasing discrimination and violence against blacks kept even middle-class African Americans within the Central-Woodland area. At the same time, discrimination in public accommodations increased. Restaurants overcharged blacks or refused them service; theaters excluded blacks or segregated them in the balcony; amusement parks such as EUCLID BEACH PARK were usually for whites only. Discrimination even began to affect the public schools. The growth of the ghetto had created some segregated schools, but a new policy of allowing white students to transfer out of predominantly black schools increased segregation. In the 1920s and 1930s, school administrators often altered the curriculums of ghetto schools from liberal arts to manual training. Nevertheless, migrants continued to pour into the city in the 1920s to obtain newly available industrial jobs. Most of these jobs were in unskilled factory labor, but some blacks also moved into semi-skilled and skilled positions. The rapid growth in the city’s black population also created new opportunities in BALDWIN RESERVOIR and the professions. Most black businesses, however, remained small: food stores, restaurants, and small retail stores predominated. Two successful black-owned funeral homes opened early in the century, the HOUSE OF WILLS (1904), founded as Gee & Wills by J. WALTER WILLS, SR., and E. F. Boyd Funeral Home (1906), founded by ELMER F. BOYD and Lewis Dean. Although the employment picture for blacks had improved, serious discrimination still existed in the 1920s, especially in clerical work and the unionized skilled trades.

Black leadership underwent a fundamental shift after World War I. Prior to the war, Cleveland’s most prominent blacks had been integrationists who not only fought discrimination but also objected to blacks’ creating their own secular institutions. After the war, a new elite, led by Fleming, Hunter, and businessman HERBERT CHAUNCEY, gained ascendancy. This group did not favor agitation for civil rights; they accepted the necessity of separate black institutions and favored the development of a “group economy” based on the existence of the ghetto. By the mid-1920s, however, a younger African American group was beginning to emerge. “New Negro” leaders such as lawyer HARRY E. DAVIS and physician CHARLES GARVIN tried to transcend the factionalism that had divided black leaders in the past. They believed in race pride and racial solidarity, but not at the expense of equal rights for black Clevelanders. The postwar era also brought changes to local institutions. The influx of migrants caused problems that black, churches were only partly able to deal with. The Negro Welfare Assn., founded in 1917 as an affiliate of the National Urban League (see URBAN LEAGUE OF GREATER CLEVELAND), helped newcomers find jobs and housing. The Phillis Wheatley Assn. expanded: a fundraising drive among white philanthropists made possible the construction of its 9-story building in 1928. The Cleveland branch of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP, est. 1912), led by “New Negroes,” expanded, with 1,600 members by 1922. The NAACP fought the rising tide of racism in the city by bringing suits against restaurants and theaters that excluded blacks, or intervening behind the scenes to get white businessmen to end discriminatory practices. The FUTURE OUTLOOK LEAGUE, founded by JOHN O. HOLLY in 1935, became the first local black organization to successfully utilize the boycott.

The Depression temporarily reversed much of this progress. Although both races were devastated by the economic collapse, African Americans suffered much higher rates of unemployment at an earlier stage; many black businesses went bankrupt. After 1933, New Deal relief programs helped reduce black unemployment substantially, but segregated public housing contributed to overcrowding, often demolishing more units than were built. Housing conditions in the Central area deteriorated during the 1930s, and African Americans continued to suffer discrimination in many public accommodations. The period from the late 1920s to the mid-1940s was one of political change for black Clevelanders. Although migration from the South slowed to a trickle during the 1930s, the black population had already increased to the point where it was able to augment its political influence. In 1927 3 blacks were elected to city council, and for the next 8 years they represented a balance of power on a council almost equally divided between Republicans and Democrats. As a result, they obtained the elections of HARRY E. DAVIS to the city’s Civil Service Commission and MARY BROWN MARTIN to the Cleveland Board of Education, the first African Americans to hold such positions. They also ended discrimination and segregation at City Hospital. At the local level in the 1930s, black Clevelanders continued to vote Republican; they did not support a Democrat for mayor until 1943. In national politics, however, New Deal relief policies convinced blacks to shift dramatically after 1932 from the Republican to the Democratic party. After World War II, Pres. Harry Truman’s strong civil-rights program solidified black support for the Democrats.

World War II was a turning point in other ways. The war revived industry and led to a new demand for black labor. This demand, and the more egalitarian labor-union practices of the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), created new job opportunities for black, Clevelanders and led to a revival of mass migration from the South. The steady flow of newcomers increased Cleveland’s black population from 85,000 in 1940 to 251,000 in 1960; by the early 1960s, blacks made up over 30% of the city’s population. One effect of this population growth was increased political representation. In 1947 Harry E. Davis was elected to the state senate, and 2 years later lawyer Jean M. Capers became the first black woman to be elected to city council. By the mid-1960s, the number of blacks serving on the council had increased to 10; in 1968 Louis Stokes was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives; and in 1977 Capers became a municipal judge for Cleveland. The postwar era was also marked by progress in civil rights. In 1945 the CLEVELAND COMMUNITY RELATIONS BOARD was established; it soon developed a national reputation for promoting improvement in race relations. The following year, the city enacted a municipal civil-rights law that revoked the license of any business convicted of discriminating against African Americans. The liberal atmosphere of the postwar period led to a gradual decline in discrimination against blacks in public accommodations during the late 1940s and 1950s. By the 1960s, both hospital wards and downtown hotels and restaurants served African Americans.