ArcelorMittal’s History of Steel Making in Cleveland

Category: Industrial Revolution 1865-1900

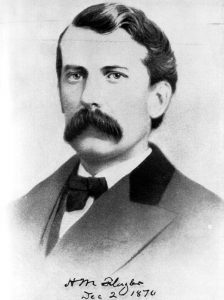

Rockefeller’s Right Hand Man: Henry Flagler

Photo: Florida Memory

Photo: Florida Memory

Rockefeller’s Right Hand Man: Henry Flagler

By Michael D. Roberts

History can be fickle. Take the story of the two men who walked Euclid Avenue in the days when its magnificent mansions made it one of the grand boulevards of the world. They were often seen together in deep conversation about their work.

One man, the taller of the two, would go on to become part of American folklore, while the one of brisk step would become an historical afterthought, obscured by the myopia of chroniclers who overlooked his importance in creating the world’s largest business venture.

The taller man was John D. Rockefeller, destined to become the richest man in the world, and the more vigorous at his side was Henry M. Flagler who played no small role in the accumulation of that wealth. They were neighbors walking to their offices where they were business partners, sharing a large partner’s desk.

They lived in a period of Cleveland history that spanned the years between the Civil War and the turn of the 20th Century. It was a period marked by achievement and wealth, one that would never be duplicated here.

The era was the catalyst for the industrialization of America, and made Cleveland the international focus for electricity, steel, oil, paint, communications, chemicals and machine tools. For the most part, history has been generous to the makers of this remarkable time. They were the predecessors of the Fortune 500.

Their names read like a manifest of industry itself: Rockefeller of Standard Oil, Wade of Western Union, Glidden, Sherwin and Williams of paint, Chisholm and Otis of steel, Brush of the electric light, White of sewing machines and trucks, Warner and Swasey of optics and machine tools, and Grasselli of chemicals.

But one notable figure of the era has not been celebrated by local historians to the extent he deserves. Largely because of his retiring demeanor and preference for the more obscure side of business along with anonymity as a hallmark of his charitable efforts, Henry M. Flagler has not been accorded a significant place in the mosaic of Cleveland history. In many city histories he has gone unmentioned.

Even the titan of the times, John D. Rockefeller, once remarked that he wished he had Flagler’s brains. Rockefeller knew better than most this man’s capabilities and some say Flagler had as much to do with making Standard Oil the most powerful company in the world as did Rockefeller himself.

By most accounts, Flagler was a dapper, good humored man whose manner radiated an ease that could be disarming, for in many ways he was a rogue, a man made for the times. Behind this charm was a cunning and toughness that was managed by an extraordinary mind. He kept an amusing, but prophetic sign on his desk that read:

Do unto others as they would do unto you—and do it first.

Flagler was nearly ten years older than Rockefeller having been born in Hopewell, New York, in February of 1830, the son of a traveling Presbyterian minister. At 14, with little formal education, but sharp of wit and a quick study, Flagler set out to make his way in the world, leaving a small town in New York to seek similar surroundings in Northwestern Ohio in a place called Republic near Sandusky.

He was able to get a job clerking for $5 a month plus room and board. It soon became evident that Flagler had a keen eye for the intangibles needed to be successful in the world of commerce. Within the year, his pay was increased to $12 monthly, but more importantly storekeeping was nurturing the flair he was developing for business.

Later, he liked to tell friends how he learned how to apply the concept of value to business deals, by selling brandy from the same barrel to customers based on what they would pay for it and not a standard price.

In 1853, Flagler married the niece of Stephen V. Harkness a prominent citizen of Bellevue who owned several businesses including a distillery. Liquor was a valued commodity and easily made in stills using the abundant grain found in rural areas. While beer was selling for 13 cents a quart, whiskey sold for half as much and it was in the liquor business that Flagler made his first fortune a few years before the Civil War.

With his strong religious upbringing, Flagler abstained from alcohol, but saw no sin in selling as much as he could to others. He had no moral aversion to profit.

Harkness was related through Henry’s step-brother, Dan Harkness, who was older. They had grown up together. Flagler’s affiliation with the Harkness family would have a fortuitous effect upon his future.

It was in the late 1850s that Flagler met John D. Rockefeller who was working for a Cleveland grain broker and traveled the hinterlands in search of business. By the start of the Civil War in 1861, Rockefeller was brokering most of the Harkness grain.

As the grim realities of war approached, Flagler did two things. He bought his way out of military service, paying $300 for a substitute to take his place in the ranks. The other thing he did was to abandon the liquor business for yet another venture, salt.

The enormous army being assembled needed to be fed and salt was a much needed preservative. And there were abundant salt springs just north in Saginaw, Michigan. In 1862, Flagler and another family member started a salt company.

At first, the Flagler salt venture was successful as the demand for it by the war drove prices up followed by the creation of many competing companies. But as the war came to an end, the demand for salt collapsed, resulting in the demise of many businesses including Flagler’s.

With the reduced demand for salt there began an effort on the part of the industry to control the price and flow of the product. Flagler witnessed the formation of a cartel intended to squeeze out competition. In fact, in later years he would become an expert in this “squeeze” and used the word to describe the elimination of competitors.

His experience in the salt business, particularly his failure to anticipate the drop in prices and the formation of anti-competitive coalition, cost him the fortune he made in liquor and proved to be an indelible lesson. He was $50,000 in debt and needed a job.

Failure never prevented him from pursuing what he enjoyed most: making money. After the demise of his salt business, he moved to Cleveland where he joined a merchant commission house, prospered, paid off his debt and bought the business.

The move to Cleveland would prove to offer an even greater fortune, one that destined Flagler to become an integral, if not principal figure, in creating the greatest industrial company the world had known. What sparked this adventure was Flagler’s reunion with his acquaintance from his merchant days in Bellevue, John D. Rockefeller.

With the discovery of oil in Pennsylvania in 1859, there began a frenzy among speculators as to how to best generate wealth from the geysering, black liquid that would change the world. It was only natural that Rockefeller’s attention would be drawn to those oil fields and the fortune that beckoned.

The main use of oil at the time was for lighting. Refined into kerosene, oil changed the way people lived, making the days longer and brighter. The demand for such an illuminator was worldwide.

Finding the oil was one thing, but extracting it from the ground, shipping it and refining it into a product that was safe and inexpensive, presented quite another set of problems. These were the problems that Rockefeller dealt with daily when he and Flagler joined in business in 1867.

Their bond had been cemented by a large investment in the fledgling company on the part of Flagler’s uncle, Stephen V. Harkness. In a short time, the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews and Flagler owned two refineries and a sales office in New York.

Samuel Andrews was a refining expert, having developed several different processes to give oil a distinctive quality at an economical cost. Rockefeller was a man of frugality and detail. He had intricate knowledge as to how many staves were in a barrel or the number of drops of solder that it took to seal a can.

Rockefeller also had an eye for talent, too, and in Flagler he found an alter ego, a man of verve and spirit that fit the reckless, if not lawless, days that characterized the Gilded Age and the robber barons that made it. Simply said, Flagler was the smartest man that Rockefeller had ever met.

This was providential, for the task before them was mercurial, presenting one financial hazard after another with no effective way to control the rapid rise and fall in prices caused by increasing competition and over production of crude oil. Within a few years the price of a barrel could fluctuate from 10 cents to $13.25. It seemed that anyone with a few dollars could open a refinery, even if it was nothing but a shed where a few barrels a day could be distilled.

In the meantime, Flagler was put in charge of the firm’s transportation issues, a key responsibility since the cost of shipping oil could make a large difference in the profit margin. Years later this would be the crux of the government’s case against the company’s efforts to become a monopoly.

Flagler’s basic job was to negotiate the rates with railroads, canal boats and pipelines. He was doing this as Rockefeller was consolidating the thirty-some refineries in Cleveland by adding them through buyouts or force.

As the firm’s capacity to produce refined oil increased, the need for cheaper freight rates became imperative to fend off competitors. The crude oil was shipped from Pennsylvania to Cleveland where it was refined. The finished product was then shipped to New York where it was sold for export.

Flagler was deft and precise in his dealings with the railroads. He guaranteed to ship a substantial amount of oil on a given line in a timely manner in return for a secret rebate. The results of an early negotiation with one line showed that the regular freight fee was $2.40 a barrel and Flagler had engineered a preferential rate of $1.65. He became expert at playing the railroads off against each other, particularly during their frequent rate wars. Secrecy was essential because other oil firms were being charged more to ship on the same line.

By 1870, the firm’s business had burgeoned enormously. Investors and other oil companies were eager to join the ranks of the prospering enterprise. Recognizing the need for more capital, but fearing the loss of control, the partners were faced with a dilemma.

Years later Rockefeller would attribute the solution to the dilemma to Flagler’s brilliance. On January 10, 1870, a company called Standard Oil was created in a brief 200-word incorporation document written by Flagler, who had no legal training, but whose idea created one of the greatest commercial ventures of all time.

At the time of the incorporation Rockefeller owned 2,667 shares. Flagler had 1,333 shares, but he voted the Harkness shares giving him equal status in the leadership of the company. There was never a serious dispute between the men over the company.

Once the new company was in existence it was voracious in its acquisitions of refineries, first dominating the Cleveland market and then reaching out into other regions. By the spring of 1872, Standard Oil was refining 10,000 barrels of oil daily, employing 1,600 workers with a weekly payroll of $20,000. Cleveland was well on its way to becoming the oil capitol of America.

Flagler liked to use the term “sweat” in association with the acquisition of competitors. That meant that there was little room for negotiation. They either had to sell to Standard or simply go out of business. The offer for these “sweated” businesses was consistent. The deal was cash or Standard Oil stock. Ironically, nearly all who took stock prospered far beyond their expectations. Many of those who had taken cash became bitter as they witnessed the rise of Standard Oil.

The immense volume of oil spawned ever more favorable freight rates and became the tool which Rockefeller and Flagler used to acquire more and more competitors. The precise date of Standard Oil’s rise to the domination of the nation’s oil industry was October 17, 1877 when it purchased Empire Transportation Company and the Columbia Conduit Company thus becoming the primary provider of oil traffic to Europe. These companies owned a combination of rail cars, shipping and pipelines. Not only did Standard Oil control the nation’s refining industry, it now was poised to control the transportation of oil.

By 1877, Cleveland could no longer contain the vast reach of Standard Oil’s international business and the company began to shift its headquarters to New York. In the fall of that year, Flagler moved to New York, thus bringing to an end his years in Cleveland.

These had been good years in Cleveland which he had enjoyed socially and as a leading member of the First Presbyterian Church. His wife, Mary, who had been ailing most of her life, was the focus of his personal concerns. At night he would return to his mansion on Euclid Avenue in the evening and read to her. One account said that he only missed two such evenings in 17 years.

As Standard Oil extended its grip on the industry, it began to be challenged by legal issues. The company was authorized to do business only in the state of Ohio. To operate a refining business in another state, on the face of it, was illegal. To skirt the law, Flagler devised a series of trusteeships to operate these businesses acquisitions.

He also conceived several plans that would consolidate the oil industry to give the company an advantage. While the initial plans failed, they drew the attention of competitors and the authorities. In April of 1879, Rockefeller, Flagler and others were indicted in Pennsylvania in connection with an attempt to create a monopoly.

While nothing came of this legal action, it was the beginning of a string of investigations and media inquiries that would extend into the next century and force anti-trust action to break the company into 33 entities.

The legal manipulations and subsequent investigations were chronicled by Ida Louise Tarbell, the foremost muckraker of her day, and author of the famous book The History of the Standard Oil Company.

Flagler’s ties with Standard Oil slowly gave way, although he remained active when it became clear that the only way for the company to keep its dominance over the oil business was to gain favored cooperation of the pipeline companies that were being built in the east.

Negotiating for the control of pipelines was Flagler’s last daily involvement with Standard Oil. He would remain linked to the company as a consultant and stockholder, but his attention and fortune was being ever more drawn to Florida where he had first visited prior to Mary’s death in May of 1881. He married twice more, having had three children by his first wife.

Flagler had always been remote and elusive with the media and his timely exit from the operations of Standard Oil allowed him to be a peripheral figure in the anti-trust scandal that would be shouldered by Rockefeller in the coming decades.

In time, the Flagler name would be more associated with the development of Florida and the construction of its railroads. He invested $50 million in the state. His days in Cleveland, from 1867 to 1877 were overshadowed by the audacity of his efforts in Florida, particularly the construction of a railroad from Daytona over the ocean to Key West.

No one was more responsible for the development of that state than was Henry Flagler. Sensing the potential of tourism, Flagler first built the 54-room Hotel Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine.

He built a bridge over the St. Johns River, opening Southern Florida to rail traffic, and purchased a hotel near Daytona. He then expanded his burgeoning rail system to Palm Beach which became the winter Mecca for American society.

He built his house, the Whitehall in Palm Beach which is now the Flagler Museum. His rambling Breakers Hotel continues as the city’s dominant hostelry.

Unwilling to bask in the sunshine of achievement, Flagler extended the Florida East Coast Railway to Biscayne Bay by 1896. Here he paused to create a city, carving out streets, installing water and electricity, and even funding the town’s first newspaper.

Famed and revered, Flagler remained a modest man and when the townspeople urged that the city be named after its benefactor, he turned it down, insisting that the better name would be that from Indian lore— Miami.

Envisioning trade with Latin American and access to the Panama Canal, he pressed on with his railway to Key West, taking seven-years of hop scotching from key to key on bridges that were engineering marvels. In 1935, a fierce storm destroyed the 107-mile railroad. As a commercial venture, it never succeeded.

In 1902, Rockefeller, now somewhat distant from his old friend and business partner, wrote Flagler the following:

You and I have been associated in business upwards of thirty-five years, and while there have been times when we have not agreed on questions of policy, I do not know that one unkind word has ever passed or unkind thought existed between us. I feel my pecuniary success is due to my association with you, if I have contributed anything to yours I am thankful.

Flagler died on May 20, 1913 in Florida at the age of 83.

The memory of Rockefeller and Flagler walking to work on Euclid Avenue and plotting their world-wide dominance of the oil industry amid the clatter of hoofs and the cry of coachmen is an image that deserves preservation as a unique moment in Cleveland history. Flagler was a personage never to be underestimated, especially by the hindsight of history.

Flagler Before Florida

1946 article on Henry Flagler’s work in Cleveland alongside John D. Rockefeller

President James A. Garfield: Civil rights activist ahead of his time (with video)

From the News-Herald, August 13, 2012

James A Garfield Essay from the Miller Center University of Virginia

For the briefest time, President Garfield was an inspiration (Washington Post 2/17/13)

Editorial from the Washington Post

For the briefest time, President Garfield was an inspiration

MOST OF OUR presidents languish in a cloud of national historical vagueness, especially those who held the office in its first century. For one thing, there were so many of them, which is what happens when republics don’t grant power for more than four years at a time. And, except for Abraham Lincoln, so few of them make really good movie material.Lincoln, of course, is in theaters everywhere in this 150th anniversary year of Emancipation, but the decades that came after that glorious episode in our history don’t seem to offer much hope for an honest sequel or another admirable president to portray.

There is one, though, who’s worth a thought on this holiday, Presidents’ Day, which is usually devoted to Washington, Lincoln and blockbuster sales events. You may have passed by the memorial to him at the foot of Capitol Hill — it’s an elaborate thing that has one large standing statue of the president and three smaller ones representing earlier stages of his eventful life.

He was James A. Garfield, who may have been the best president we never had, or hardly had. Garfield was fatally wounded only months into his presidency by a deranged office seeker with a handgun, and the memorials to him — statuary, parks, streets, schools here in Washington and elsewhere — reflect not just the nation’s grief over his martyrdom but also a genuine admiration felt across a great part of the country and especially among its most downtrodden.

Garfield was a poor boy (last of the log cabin presidents) who lost his father early, worked his way through school, and went on to become a professor, Civil War general, businessman and congressman.

He was chosen for the 1880 Republican presidential nomination even though he didn’t seek it and tried to dissuade the delegates at the deadlocked convention from stampeding to him. (Talk about a story line that would test the credulity of modern American audiences.) And he took office reluctantly, sensing that he would never see his Ohio farm again.

Garfield was an upright man but human, and he made mistakes and enemies here and there. But he was a forceful and widely respected advocate for what he believed in, inspired trust among many and felt strongly on the great issue of his day — the future of newly emancipated Americans. He was also a powerful orator, and in his inaugural address he delivered an impassioned defense of civil rights, the likes of which was not to be made by another American president for nearly a century.

“The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787,” he said. “NO thoughtful man can fail to appreciate its beneficent effect upon our institutions and people. It has freed us from the perpetual danger of war and dissolution. It has added immensely to the moral and industrial forces of our people. It has liberated the master as well as the slave from a relation which wronged and enfeebled both. It has surrendered to their own guardianship the manhood of more than 5,000,000 people, and has opened to each one of them a career of freedom and usefulness. It has given new inspiration to the power of self-help in both races by making labor more honorable to the one and more necessary to the other. The influence of this force will grow greater and bear richer fruit with the coming years.”

There was more along those lines, and it bears reading. Moreover, Garfield appointed four black men, among them Frederick Douglass, to posts in his administration. We are left to wonder today what a president of conviction and conscience such as Garfield might have done to rouse the country and lead it against the vicious new institutions of repression and virtual reenslavement that were taking hold in the American South, with the silent acquiescence of the North.

We will never know, of course, what the limits of his leadership might have been, but it would seem, from the grief at his passing and the memorials that remain, that he was a president who left more of a mark on the people’s consciousness in a few months than some others have in four years and more.

History of Child Care in Northeast Ohio (thru 1998) from Encyclopedia of Cleveland History written by Dr. Marion Morton

CHILD CARE – The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

CHILD CARE. Since the mid-19th century, Cleveland has cared for children needing residential or day care or medical services. Although child care has been both a private and a public responsibility, the public sector has played an increasingly significant role since the 1930s. The first public institution to care for children was the City Infirmary, built in 1837 to house all dependents, including the ill, elderly, disabled, and insane. In 1858 the House of Correction, also called the House of Refuge, opened for vagrant or delinquent children under the age of 17, operating in conjunction with the city workhouse from 1871 until closing in 1891. From 1891-1901, delinquent children were kept in the Cuyahoga County Jail. Some public funding supported temporary shelter and training for dependent children in the City Industrial School (1856-71), founded by METHODISTS in 1853 as the “Ragged School.”

However, private charities, often with strong religious ties, sponsored most of the city’s 19th century child care. Protestants, Catholics (see CATHOLICS, ROMAN) and Jews (see JEWS & JUDAISM) established several institutions for children from the mid-19th to the 20th centuries (see ORPHANAGES). These institutions provided long-term residential care while child-placing agencies provided temporary shelter and placed children in foster or adoptive homes. The CHILDREN’S AID SOCIETY was organized in 1858 as an outgrowth of the City Industrial School. The Cleveland Humane Society (like others around the country, at first the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) began to serve children in 1876, charged with enforcing a new state law that prohibited cruelty to children. The society investigated cases of neglect, abuse, or abandonment and was empowered to remove children from their parents and place them in orphanages or foster homes if necessary. In most cases, however, the Humane Society simply admonished parents or forced them to supply adequate financial support. It also administered Lida Baldwin’s Infants Rest for foundlings (1884-1915). In 1887 the Lutheran Children’s Aid Society was established for children of LUTHERANS.

Religious institutions also provided preventive or protective services for children judged to be neglected, delinquent, or predelinquent. In 1869 the SISTERS OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD opened their convent for young women, and in 1892 the WOMAN’S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION, NON-PARTISAN, OF CLEVELAND, opened its Training Home for Friendless Girls. These institutions purported to reform and reclaim young women through religious training in a familial and domestic setting. Private organizations sponsored daycare facilities, beginning with the CLEVELAND DAY NURSERY AND FREE KINDERGARTEN ASSN., INC. (1882).

Four medical facilities especially for, children were established around the turn of the century: Rainbow Cottage (1887) for convalescent children, which became Rainbow Hospital for Crippled & Convalescent Children (1913); the Children’s Fresh Air Camp (1889), later HEALTH HILL HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN; Babies’ Dispensary & Hospital, a free milk dispensary (1904) which later added a clinic (1907); and the Holy Cross House for crippled and invalid children (1903), administered by the EPISCOPALIANS (Diocese of Ohio). In 1925 the Babies’ Dispensary became part of UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS CASE MEDICAL CENTER (UH), joined by Rainbow Hospital in 1971 to form Rainbow Babies & Childrens Hospital of UH.

In 1909 a White House Conference on Dependent Children signaled the interest of the Progressive Era in child welfare and helped establish 2 trends that would dominate child care through the century: the shift from institutional to noninstitutional care and the increase in public funding and management. The conference took the official position that “home life” (as opposed to institutional life) was best for children; in 1910 the Western Reserve Conference on the Care of Neglected & Dependent Children reiterated that preference. The establishment of CUYAHOGA COUNTY JUVENILE COURT in 1902 marked a new recognition of public responsibility. Created in reaction to deplorable conditions of the children’s facilities in the city jail, the court provided for dependent and neglected children. Delinquent children were placed on probation, in a public reformatory institution such as the Hudson Boys’ Farm (1903) or BLOSSOM HILL SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (1914), or in a private protective facility. The court also collected child support from negligent parents. In 1913 the State of Ohio passed a mothers’ pension law, providing funds for widowed or deserted mothers to continue to care for their children.

The growing preference for noninstitutional care gave child-placing agencies new importance. Because there were no county children’s homes, in 1909 Cuyahoga County provided funds to the Humane Society to place children in boarding homes. In 1913 the society also received city monies to establish systematic child-placement. In 1921 the Children’s Bureau was established to standardize the placement of Protestant and Catholic children in foster and adoptive homes. The Welfare Assn. of Jewish Children, (later the JEWISH CHILDREN’S BUREAU) handled the placement of Jewish children. Several nonresidential services also developed, such as the WOMEN’S PROTECTIVE ASSN. (1916), which became the Girls’ Bureau (1930), working closely with juvenile and municipal court probation officers, and the Jewish and Catholic Big Brother/Big Sister programs (est. 1919-24, see BIG BROTHER/BIG SISTER MOVEMENT).

Despite the noninstitutional preference, new facilities for adolescents were, established, partly in response to concerns about delinquency and CRIME. The Catholic Diocese opened St. Anthony’s Home for Boys (1906) and the CATHERINE HORSTMANN HOME for high school girls (1907). The work of the Convent of the Good Shepherd was divided between the Sacred Heart Training School, which admitted girls referred by juvenile court, and the Angel Guardian School, which sheltered dependent girls. The Humane Society opened Leonard Hall, formerly Holy Cross House, for high school boys.

The community responded to the needs of young children as well. The Cleveland Day Nursery & Free Kindergarten Assn. was founded in 1983. Since kindergartens had become a public responsibility in 1897 (see EDUCATION), nursery schools and daycare centers gradually replaced the association’s kindergartens. In 1922 the Sisters of the Holy Humility of Mary opened Rosemary Home for crippled children (later ROSE-MARY CENTER). Orphanages merged, moved to the SUBURBS, expanded, and broadened services to include “troubled” children.

The Depression accelerated the trends toward public responsibility and noninstitutional care. As private funds dwindled, the number of children admitted into the city’s child-care institutions dropped significantly: from 2,139 in 1928 to 1,346 in 1930. Public funding, particularly federal, became more important, and public agencies, particularly the county, assumed new responsibilities. In 1930, for example, the Cuyahoga County Child Welfare Board took over the placement of more than 1,000 children from the Humane Society and the Welfare Assn. for Jewish Children. The county also maintained a detention home, offering children temporary shelter. In 1935 the Social Security Act provided federal funds, to be supplemented with local dollars, for Aid to Families of Dependent Children (AFDC). Since the 1930s, both county and federal governments have expanded these roles. AFDC has borne chief responsibility for care of dependent children, usually within the family. From 1979-80, 90,300 Cleveland residents received AFDC funds. The Cuyahoga County Department of Human Services provided child placement in foster and adoptive homes and private facilities as well as daycare and protective services. The county also maintained the Metzenbaum Children’s Center, a temporary shelter and diagnostic facility; a juvenile detention home; and the Youth Development Center in Hudson, formed by the merger of Cleveland Boys School and Blossom Hill. The Ohio Department of Youth Services administered Cuyahoga Hills Boys School for juvenile offenders.

Since the 1940s, private child-care agencies have merged and diversified, most specializing in counseling in residential or nonresidential settings. When AFDC and other public-relief programs diminished the need for institutional care for dependent children, orphanages and, child-placing agencies shifted their focus to children with emotional or behavioral problems. Residential protective facilities included Marycrest School, formerly the Sacred Heart Training School, the CRITTENTON HOME (which served unwed mothers prior to 1971), BOYSTOWNS, and group homes run by the Augustine Society and the West Side Ecumenical Ministry. The Catherine Horstmann Home began to serve retarded young women.

Family service agencies provide a wide range of programs. In 1945 the Humane Society and the Children’s Bureau combined to form Children’s Services, which in 1966 absorbed a former orphanage, the Jones Home (see JONES HOME OF CHILDREN”S SERVICES, INC.). Children’s Services has offered foster care, unmarried-parent counseling, daycare, and, in the Jones Home, care for emotionally disturbed children. The Lutheran Children’s Aid Society has provided family counseling and foster-home placement. Catholic Social Services and the Jewish Children’s Bureau offered child placement and daycare while Catholic Social Services and the JEWISH FAMILY SERVICE ASSN.have counseled families and individuals.

The increase in daycare facilities reflects the growing numbers of mothers in the paid workforce since World War II. In 1949 only the Day Nursery Assn., the JEWISH DAY NURSERY, and the WEST SIDE COMMUNITY HOUSE sponsored daycare. In 1962 9 agencies provided daycare to about 1,000 children. By 1982, in addition to Catholic and Jewish organizations, the CENTER FOR FAMILIES AND CHILDREN, the GREATER CLEVELAND NEIGHBORHOOD CENTERS ASSN., the SALVATION ARMY, KARAMU HOUSE, and federal, state, and local funds supported a wide range of daycare options. The total 1982 capacity of these nonprofit centers was 6,140 children.

Public funds have enabled these private child-care institutions and agencies to expand and diversify: public agencies have often bought specialized professional services from them, like daycare, psychiatric and medical care, and counseling. The availability of public monies, however, depends upon the state of the economy and the spending policies of elected officials.

Marian Morton

John Carroll Univ.

Mark Hanna aggregation

Mark Hanna by Frederic C. Howe

Chapter about Marc Hanna in Confessions of a Reformer by Frederic C. Howe