From the Plain Dealer December 25, 1994

ROCKEFELLER’S LEGACY JOHN D.’S RICHES HELPED BUILD CLEVELAND INDUSTRIALLY, EDUCATIONALLY, CHARITABLY AND RECREATIONALLY

Plain Dealer, The (Cleveland, OH) – Sunday, December 25, 1994

Author: JEFF HAGAN

Imagining a world that might have been, a world the same save one life, seems the stuff of fiction.

Movie director Frank Capra brought this story to the screen in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” starring Jimmy Stewart. In this movie, the moral of Capra’s musings is that even the little guys of this world have an impact. Their lives change the world in ways we may not fully imagine.

What if we imagine Cleveland without one life? What if that one life was one that made a broad mark on the city’s history?

What if we imagine Cleveland without John D. Rockefeller?

The legacy of Rockefeller in Cleveland is not easily defined. He was the richest man in America. He donated millions of dollars to causes and charity, yet how does one account for the refiners Rockefeller put out of business, or the pain and labor among those whose struggle created Rockefeller’s phenomenal wealth? Would those contributions have been necessary if his exploitation of the American economy – and its workers – had not been equally phenomenal?

Regardless of the answers to these questions, one thing is certain: For better or worse, Cleveland would not be Cleveland if Rockefeller had not lived here for three decades.

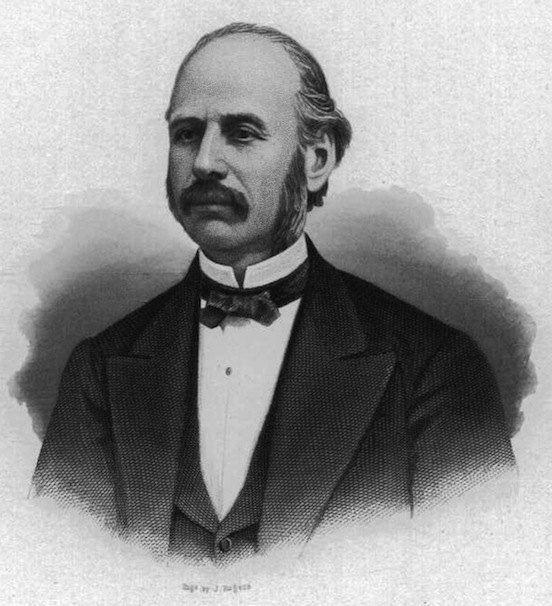

A native of New York state, Rockefeller came to Strongsville in 1853, boarded in Cleveland as a teen and graduated from Central High School.

After attending business classes, he went to work for the commission house of Tuttle & Hewitt on Merwin St. in the Flats in 1855. It was his first and last employer.

In 1859, Rockefeller entered a partnership with Maurice Clark, continuing in the wholesale business. The firm profited handsomely from its government contracts, particularly during the Civil War. With its good margins and good credit, and a new partner, Samuel Andrews, Rockefeller invested in the fledgling oil industry, eventually building a refinery where Kingsbury Run hits the Cuyahoga River and leaving the commission business altogether to devote himself to oil.

After working with various partners, Rockefeller incorporated the Standard Oil Co. in 1870 with a group of men who would make their names and fortunes with his company. Rockefeller was its largest stockholder.

John Grabowski, director of research at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, conducts a slide show about the history of Cleveland. It contains two revealing slides, shown in succession. The first is a photo of a couple of dozen men gathered at Cliff House, a Rocky River resort.

“This is a picture of the oil trade in Cleveland in the 1860s,” Grabowski says. The next slide is of John D. Rockefeller standing alone.

“This,” Grabowski says, “is a picture of the oil trade in Cleveland in the 1870s.”

That portrait depicts the entire U.S. oil industry by the 1890s. From early on in the oil business, Standard Oil tried to gain control over every aspect of the industry, attempting to sop up profits and force out competition.

Of one group of recalcitrant independent producers Rockefeller once said, “A good sweating will be healthy for them.”

To ship the refined oil more cheaply, Standard did everything from wresting low rates and rebates from the railroads to going into the barrel-making business. By 1872, Standard Oil controlled 21 of Cleveland’s 26 oil refineries; by 1882, Standard Oil controlled 90% of the nation’s refining capacity, and a few politicians as well.

Rockefeller earned the ire of independent oil producers, whose prices he ruthlessly undercut until they capitulated, either selling out to him, consolidating with Standard Oil or going out of business. In 1872, The Plain Dealer reported on Rockefeller’s early cartel, the South Improvement Co. That report turned public opinion against Standard Oil. This was followed by an 1881 muckraking piece in the Atlantic Monthly called “The Story of a Great Monopoly.”

Still, the company’s monopolistic practices continued until the federal government finally stepped in and, finding the company had violated antitrust laws, broke up the company in 1911.

By then, John D. Rockefeller was already in semi-retirement, a state he reached at age 36. Rockefeller had moved his headquarters to New York in 1884, having outgrown the financial capacity of Cleveland, though he continued to summer at the family’s Forest Hill estate east of Cleveland until his wife died in 1915, after which he seldom visited. (Rockefeller last visited Cleveland in 1917.) He died in 1937 at age 97. He and his wife, Laura, are buried in Lake View Cemetery, where his 71-foot obelisk monument is among the most popular attractions for visitors.

Rockefeller, a devout Baptist who remained pious even while his company was its most ruthless (perhaps adding to the public distaste for the man), never felt he had done anything immoral, and he even liked to say his riches came from heaven.The fact that the latter half of his life was devoted to giving away large portions of the money he made in the first half have led some to conclude he did have an eye toward better public relations.

However, Rockefeller had created a strong pattern of giving long before his patterns of getting made him so very rich. He kept detailed ledgers in which he recorded his net worth and donations (along with just about every other expenditure he ever made). The ledgers reveal contributions made to a variety of organizations even when his paycheck was a pittance. Still, at least one minister called a Rockefeller contribution to his organization “tainted money” because of the capitalist’s sullied reputation. The check was nonetheless cashed by other officers of the church.

If Rockefeller merely wanted good publicity, or even to be remembered well, he could have shown, as other philanthropists of his day did, a propensity to attach his name to the buildings, parks and institutions he helped make possible. Names connected with Rockefeller are still visible on a handful of landmarks in Cleveland and the other cities his generosity reached, but not nearly as many as there could be, and not as many as his contemporaries, like Andrew Carnegie, left behind.

“This goes against the grain of a lot of 19th-century philanthropy,” says Darwin Stapleton, a former Case Western Reserve University professor who is now director of the Rockefeller Archive Center in North Tarrytown, N.Y.

Rockefeller’s presence in Cleveland is still felt strongly today, if not always recognized. But it doesn’t take Frank Capra, who imagined the life of a town with one important person removed in his movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” to understand Rockefeller’s legacy in Cleveland. It just takes a little looking around town.

The Rockefeller Buildings

More than one Clevelander has remarked that if John D. Rockefeller hadn’t moved to New York, the world-famous Rockefeller Center would be located here in Cleveland. Maybe. But Rockefeller’s vast financial empire required the big banks of the big city, and when he built, he built according to scale. That’s why Cleveland’s Rockefeller Building, on Superior Ave. at W. 6th, stands 17 stories high.

But it wasn’t always the Rockefeller Building. For a time, it was the Kirby Building.

It was built by Rockefeller between 1903 and 1905 for a million dollars. Reluctantly, and after a lawsuit forced him to, he sold it to Josiah Kirby, a shady businessman who ran insurance and mortgage businesses in the building. Kirby changed the name of the building to his own and put the name in lights atop the structure, which is said to have angered Rockefeller. The name even stuck after Kirby sold the building, so Rockefeller had his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., buy the building for nearly $3 million and rename it the Rockefeller Building. When he sold it later, part of the deal was that the name was to stay attached to the building forever.

The Heights Rockefeller Building stands on the corner of Mayfield and Lee Rds. in Cleveland Heights, on the edge of the old Forest Hill estate. The charming brick structure was at one time the entry building to John Jr.’s real-estate development at Forest Hill. Junior had planned to develop his family’s former estate by building 600 homes for the burgeoning class of white-collar workers, but the economy collapsed and only 81 were built. These French Norman-style homes – simply called “Rockefellers” – can still be seen in the Forest Hill area, contrasting to the modern and less stately homes that surround them.

“These were houses built for the ages,” says Grabowski.

While there is wild speculation that Rockefeller stayed away from the early antecedents of Case Western Reserve University (Case School of Applied Science and Western Reserve University) because of a rivalry with the schools’ main patrons, the Mathers, Rockefeller did eventually grant large contributions to the Cleveland institution. His name can be found atop the school’s physics lab, one of the two buildings he financed on the campus to the tune of $200,000. (The other was demolished.) He also earlier gave $2,500 to help buy joint property for the two schools. All told, Western Reserve University received nearly $1.6 million from Rockefeller, his General Education Board and the Rockefeller Foundation by the time he died in 1937.

The BP Building, owned by British Petroleum which bought Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio), is a few steps away from the early Standard offices when John D. Rockefeller first incorporated on Euclid Ave. Rising 45 stories, it was completed in 1985. If Rockefeller had not been in Cleveland, certainly the BP Building would not.

“That’s perhaps the ultimate legacy, right here on Public Square,” says Grabowski.

Rockefeller’s legacy is felt elsewhere around the square. An early member and supporter of the Western Reserve Historical Society who was made a lifetime honorary vice president, Rockefeller supplied the organization with one-quarter of the $40,000 purchase price for the Society for Savings Building – the largest of the gifts given. The building still sits across the northeast quadrant of the square. Rockefeller also is reported to have chipped in $50 for the $4,500 statue of Moses Cleaveland.

Another building that Rockefeller is in part responsible for is the Arcade, in which he was a major investor. The head of the company that built the Arcade in 1890 was Stephen V. Harkness, a Standard Oil partner of Rockefeller’s.

The Rockefeller Parks

The most widely known of the park land donated by Rockefeller is, of course, Rockefeller Park, the meandering green blur one passes while ignoring the 25 mph signs on Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. The city of Cleveland bought this section of land along Doan Brook to link Wade Park with the lakefront Gordon Park, and, at the celebration of the city’s centennial, it was announced Rockefeller was reimbursing the city the $300,000 it paid for the land. Rockefeller then gave $100,000 for a bridge to carry Superior Ave. over the Doan Brook valley, on the condition that more money be raised locally. One source, a book by Grace Goulder called “John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years,” says the Rockefeller family also donated an additional 278-acre stretch near the Shaker Lakes to the city.

John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated nearly a third of the family’s Forest Hill estate, which the family no longer used as a summer home, to create Forest Hill Park. It is set on rolling, wooded hills in East Cleveland and Cleveland Heights.

All told, it is estimated in the family archive center that the Rockefellers gave gifts worth more than $865,000 in land or cash to buy and maintain parks.

Rockefeller also donated land for private use.

The Rockefeller Charities

At the Rockefeller Archive Center, 56 million pages of documents deal with the family’s personal philanthropy. By the time Rockefeller died, he had given away $530 million, and by the time his son died, he had given $561 million away, through personal donations or to charities set up by the family. Some of these contributions came at important times to an institution, allowing it to buy a building or create an endowment at a key juncture. Though Rockefeller’s gifts touched 88 countries, many of his early contributions were of great benefit to Cleveland institutions and individuals.

Beginning in the 1890s, Rockefeller had a staff sort through the requests and evaluate their worthiness, which sometimes turned off the spigot to a group.

“He was looking for places that had a good structure in place for management,” says Kenneth Rose, assistant to the director of the Rockefeller Archive Center, who studied the exhaustive manner in which Rockefeller investigated a charity’s effectiveness.

According to Darwin Stapleton, the center’s director, Rockefeller pioneered two kinds of philanthropy that took root in Cleveland and spread around the country: the general purpose foundation and the community foundation. After Rockefeller created the General Education Board in 1902 and the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913, he continued to be generous with his old hometown. “Cleveland is overrepresented in the giving of these two organizations up until about the ’50s,” says Stapleton.

Rockefeller gave important early support to the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People, which today exists as the Eliza Bryant Center on Wade Park Ave. He also helped to fund the Children’s Aid Society and served on its board of trustees. The organization eventually concentrated its efforts on a Detroit Ave. school and farm, which had been donated by Eliza Jennings. The society today provides services to emotionally disturbed children and their families at the same Detroit Ave. site. While Rockefeller was extremely generous to the YMCA and YWCA, donating large portions of construction costs for new buildings, these organizations would likely have gone on, owing to the broad base of support they enjoyed in the city.

Rockefellergave matching funds to purchase a home on Prospect Ave. to create the Baptist Home of Northeast Ohio for aging and lonely Baptists, which was started by members of his Euclid Ave. Baptist Church. This eventually grew into the Judson Retirement Community, still operating today with Judson Manor and Judson Park, two East Side residential facilities.

Alta House, named for Rockefeller’s daughter, began as a day nursery serving the Mayfield Rd. and Murray Hill neighborhoods, and is one of the city’s oldest settlement houses. Rockefeller built and expanded buildings, including a pool and gymnasium, and donated substantial sums to support operations, until 1922, when the family was relieved of its role by the Cleveland Community Fund, a forerunner of United Way. Alta House now operates youth programs and senior citizens services out of the former gymnasium building.

Shiloh Baptist Church and Antioch Baptist Church, two important African-American congregations in the city, both received significant gifts from Rockefeller, including matching funds for new buildings. Although the structures he funded have since been torn down, his timely contributions may have helped, along with the congregations and African-American leaders, to keep these churches together. Similarly, Rockefeller made a challenge grant to the Western Reserve School of Medicine at which Stapleton calls a hinge point, taking it from a regional to a national medical school.

John L. Severance, the son of one-time Standard Oil treasurer Louis Severance, and once a Standard employee himself, pledged $1 million to build Severance Hall on the condition that twice that amount be raised for a permanent endowment. John D. Rockefeller Jr. kicked in $250,000 for the fund.

“The great gifts of our Hall [Severance] and the endowments that largely support the Cleveland Orchestra today were made possible by the Standard Oil fortunes … inherited by the Severances, the Blossoms and the Boltons,” said Adella Hughes, founder and manager of the Cleveland Orchestra in 1947. BP America, son of Standard Oil, has continued to support the orchestra, including funding national radio broadcasts and recordings for the world-class institution. Severance Hall, therefore, could be seen in part as yet another Rockefeller building in Cleveland.

Rockefeller’s influence in the world of philanthropy sometimes takes on a more abstract character. For instance, Frederick Goff, Rockefeller’s attorney until 1908, and the man who represented him during the antitrust litigation, may have been influenced by Rockefeller’s example when he created the Cleveland Foundation in 1914.

Rockefeller And Associates

Rockefeller’s practice of gobbling up competitors and controlling all ends of an industry’s operations presaged modern corporate forms of consolidation and standardization, a legacy felt in other industries here in Cleveland and elsewhere.

“Rockefeller in one sense monopolized the oil industry,” says John Grabowski. “In another sense, he rationalized it.” Most importantly, he did it here in Cleveland.

“It was not the natural center of the petroleum industry,” says Stapleton. “He, by the sheer power of his vision, directed the petroleum industry’s product primarily to Cleveland.”

The buildup of infrastructure and other businesses, everything from barrel-making to banking, was in part a result of such a large corporation maintaining a headquarters here, a point that could arguably apply to Standard Oil’s descendant, BP America. Among Rockefeller’s legacies then, says Stapleton, are “the drawing of capital to the city, the creation of jobs, the petroleum business, transportation, allied chemical business, manufacturers` products associated with petroleum,’ along with the budding telegraph industry.

Stapleton adds it is no accident that Western Union came to Cleveland, where Rockefeller needed such instantaneous contact with markets and refiners in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New Jersey and New York.

Rockefeller also pulled together teams of bright people who showed promise and made many of them very wealthy. These people have left their own formidable legacies to the city, forever wedded to that of Rockefeller.

Samuel Andrews, an early partner, helped build the Brooks Military School, out of which eventually grew Hathaway Brown, and was a trustee to Adelbert College. Stephen Harkness provided important financial support to the forerunner of Standard Oil and joined when the company incorporated. Besides joining Rockefeller in contributing to the Central Friendly Inn (now just called the Friendly Inn), Harkness helped to bring Western Reserve University into Cleveland from Hudson.

Another associate, Oliver H. Payne, made his money by consolidating his firm and joining Standard Oil. He, too, made large contributions to Western Reserve University, as well as St. Vincent Charity and Lakeside hospitals. John Huntington installed fireproof roofing for a Standard Oil building and was offered stock or cash for payment. He took the stock, became extremely wealthy, and left bequests including the John Huntington Benevolent Trust for charities and the funds to help found the Cleveland Museum of Art. His summer home in Bay Village was acquired by the Cleveland Metroparks and was named Huntington Reservation in his honor.

Among those influenced by Rockefeller was Cyrus Eaton, a young boy who worked summers at Forest Hill and whose early business ventures Rockefeller supported. It was at his summer job that Eaton became friends with Dr. William Harper, president of the Rockefeller-founded University of Chicago, and his son, Sam. The Harpers had traveled to Baptist missions in Russia, and kindled Eaton’s interest in the nation, eventually bringing him to a leadership role in promoting good U.S.-Soviet relations during the Cold War, while Eaton was a major industrialist with Republic Steel.

Eaton donated land to the forerunner of the Metroparks, was a founder and trustee of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, helped to create Fenn College from the YMCA night school and was a benefactor of Case School of Applied Science.

The presence of John D. Rockefeller can be felt in far-ranging areas, from his large role in making Cleveland a national center for industry to mentoring other budding industrialists, developing new forms of corporate organization and creating institutions that continue to serve cultural and material needs decades after they were founded.

He may never have intended to make his presence felt so long after his death, but his was one life that the city of Cleveland can never imagine itself without.

In the annals of Cleveland business, no man was smarter, more controversial and made more money than John D. Rockefeller, whose vision and management style set the stage for a corporate America that became the envy of the world. Along the way, he became the wealthiest man in that world.

In the annals of Cleveland business, no man was smarter, more controversial and made more money than John D. Rockefeller, whose vision and management style set the stage for a corporate America that became the envy of the world. Along the way, he became the wealthiest man in that world.