Transportation In Greater Cleveland (PDF)

by James A. Toman

Technology Creates a Modern Transportation Era For thousands of years, humankind depended on muscle power, animal or human, to move people and goods from one land location to another. that would finally change in the 18th century with the invention of the steam engine. It revolutionized the way in which work was accomplished, and it ushered in the “modern age.” The first successful use of steam power for transportation was the work of John Fitch. In 1787 his steamboat traveled along the Delaware River in Philadelphia. It was Robert Fulton, in 1807, however, whose steamboat Clermont successfully plied the Hudson river between New York City and Albany, that ultimately marked the arrival of the age of the steamboat. While the challenge of using steam to propel shipping along the waterways had been met, it wasn’t until 1825 that its application to land travel arrived. This took the form of a steam locomotive, invented by George Stephenson in England. It was four years later, in 1829, that his Rocket locomotive traveled between Liverpool and Manchester averaging 30 miles per hour. The Rocket proved that steam railroads were the wave of the future. The first steam train serving Cleveland came in 1850. It connected the city to Chicago and New York City.

For thousands of years, humankind depended on muscle power, animal or human, to move people and goods from one land location to another. that would finally change in the 18th century with the invention of the steam engine. It revolutionized the way in which work was accomplished, and it ushered in the “modern age.” The first successful use of steam power for transportation was the work of John Fitch. In 1787 his steamboat traveled along the Delaware River in Philadelphia. It was Robert Fulton, in 1807, however, whose steamboat Clermont successfully plied the Hudson river between New York City and Albany, that ultimately marked the arrival of the age of the steamboat. While the challenge of using steam to propel shipping along the waterways had been met, it wasn’t until 1825 that its application to land travel arrived. This took the form of a steam locomotive, invented by George Stephenson in England. It was four years later, in 1829, that his Rocket locomotive traveled between Liverpool and Manchester averaging 30 miles per hour. The Rocket proved that steam railroads were the wave of the future. The first steam train serving Cleveland came in 1850. It connected the city to Chicago and New York City.

The use of steam locomotives for city transportation, however, was really not feasible. The noise, smoke, and soot that accompanied them made them unsuitable for an urban environment. As a result, the city version of the stagecoach, the horse-drawn omnibus, continued a while longer in cities like Cleveland as the main means of transit.

The use of steam locomotives for city transportation, however, was really not feasible. The noise, smoke, and soot that accompanied them made them unsuitable for an urban environment. As a result, the city version of the stagecoach, the horse-drawn omnibus, continued a while longer in cities like Cleveland as the main means of transit.

The omnibus was faced with its own set of problems. The omnibus mainly had to travel along unpaved streets, which after rain or snow, often became impassable for the clumsy vehicles. thus, the idea of putting the omnibus on rails built in the streets offered real advantages. These street railways, as they were known, were pulled by teams of h

In 1860 the population of Cleveland reached 43,417, an increase of over 250% from the previous census in 1850. The increase in numbers also meant that people were spread over a larger area of the city, making transportation increasingly important. This trend made the investment in street railways ever more attractive. Entrepreneurs interested in laying rails in city streets needed to apply to the city of Cleveland for a franchise. By 1875 nine separate companies were operating street railways in the city. Street railway leaders, however, were not content to continue operating with horse- drawn cars, and so the search continued for a suitable replacement power source.

In 1879 Cleveland inventor Charles Brush had installed electric lighting along Public Square. Its reliability as a lighting source suggested that it might also be the answer to powering the street railways. Two other Clevelanders, Edward Bentley and Charles Knight, gave the idea its first successful trial. On July 26, 1884, a mile of electrified line on Central Avenue was tested. Cleveland became the first city in the nation to have an electricity- powered streetcar line. the Bentley-Knight system, utilizing a trough buried between the rails, encountered problems, especially when rainwater would flood the power conduit. It was discontinued after a month of operation.

Another system was then under development in Richmond, Virginia, the work of Frank J. Sprague. His system brought electric power to the streetcar via an overhead wire. A trolley pole on the car’s roof took in the power and transferred it to the car’s electric motors. It was the Sprague system that proved most effective and was adopted in most cities across the country. Cleveland opened its first Sprague installation on Euclid Avenue, from East 118th Street to East 55th Street, in December 1888. Electrification from East 55th Street to Public Square was completed in July 1889.

Even as electricity brought about the triumph of the streetcar in public transportation, in Germany Karl Benz began building the first automobiles, powered by internal combustion engines. the automobile would soon challenge the dominance of the streetcar, and within 50 years it would become the dominant force in urban planning.

Creating a Transportation System

While electrification represented significant technological progress for public transit, it also meant that additional capital would be needed to build electrical power plants, substations, and the overhead distribution network. Recognizing the advantages of economies in scale, the street railway operators saw an answer in mergers between the separate companies.

By 1893, the various independent lines came under the control of just two companies, the Cleveland Electric Railway Company and the Cleveland City Railway Company. In 1903 Cleveland city railway company merged into the Cleveland Electric Railway Company. The consolidation, however, did not bring peace to the local public transit scene.

By 1900 Cleveland’s population had jumped to 381,768. It was the seventh largest city in the nation. automobile ownership that year was estimated at 150. this meant that public transit was of vital importance to almost every Clevelander, and naturally there were different concepts about how public transit should be operated and managed.

The Cleveland Electric Railway Company was a private company. It viewed its investment in public transit as a sound way to generate dividends for its stockholder. Ridership in 1903 passed the 100,000,000 mark, and with fares set at a nickel, the company was showing a solid profit.

The railway company’s vision about public transit, however, contrasted sharply with that of Cleveland Mayor Tom Loftin Johnson, who led the city from 1901 to 1909. Johnson, a Progressive in public policy thinking, believed that public transit was a service which should operated by the city at the lowest possible cost to passengers.

At the time Ohio law did not authorize cities to own public transit operations, so in the interim, Johnson and his allies created the Municipal Traction Company. Organized as a holding company, its aim was to lease Cleveland electric railway’s lines and operate them in trust until such time as city ownership became possible. True to his Progressive ideals, Johnson advocated a three-cent fare instead of the five-cents which was then being charged.

Naturally, his point of view alarmed Horace Andrews and John Stanley, the leaders of the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, who were not interested in ceding control of their properties or finding their profits squeezed. But Johnson’s allies had the upper hand. The city could choose not to renew the franchises under which various lines were then being operated. Facing that threat, Cleveland Electric Railway Company reluctantly agreed to lease its lines to a newly created Municipal Traction Company.

The battle, however, was not over. With reduced income, the municipal traction company was unable to meet its workers’ wage demands. to save money routes were revised, much to the riders’ displeasure. a strike followed, but when that had been settled, disgruntled employees conveniently chose not to collect fares from the passengers. Ultimately municipal traction company could not pay its debts, and in 1908 the local streetcar lines went into receivership.

The case was held in the federal district courtroom of Judge Robert W. Tayler. He determined that the street railways belonged to the private company, renamed as Cleveland Railway Company. He also held that the railways operated over streets belonging to the public. His solution was to set up a 25-year franchise for the Cleveland Railway Company, but to make it subject to oversight by a Cleveland Traction commissioner. The commissioner was authorized to determine routes and schedules for the company, but the company was to be entitled to an annual 6% return from its operations. the new organizational scheme thus recognized the interests of both private and public factions. It went into effect on March 2, 1910.

The privately-owned Cleveland Railway Company operated the city transportation system until 1942, when the city of Cleveland established the Cleveland Transit System and purchased the railway’s assets.

Building a union railroad station—another battle

Just as the streetcar industry was critical for transportation within the city, the steam railroad played that same role for transit and commerce between cities. Cleveland was in need of a new passenger railroad depot.

While the traction issue had been settled by a court, the site for a new Cleveland railroad station was to be decided by the voters. It was a contest between a lakefront site at the northern end of the mall and one on Public Square, the former favored by the city’s establishment and the latter by two entrepreneurs on the rise – Oris Paxton and Mantis James Van Sweringen.

In 1903, behind the leadership of mayor Tom Johnson, a Group Plan Commission unveiled a plan which would clear 101 downtown acres. Its centerpiece was a 500-foot wide central mall, stretching from Rockwell Avenue north to the bluff overlooking the lake front railroad tracks. New government buildings would be built along the mall perimeter, giving Cleveland an impressive new civic center, befitting the city’s ever increasing status. Most of the buildings proposed in the Group Plan were built. Plans for a new railroad station, however, languished.

At the time Cleveland had several railroad stations, each serving different railroad companies, but the main Union Depot, at the foot of West Ninth street, was the busiest. It served both the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads. It had been built in 1865, and it was in deplorable shape and filthy from decades of pollution from the steam locomotives that served it. The first site to greet most visitors to the city, it was a civic embarrassment.

Ultimately, the decision about the location of a new station was left to the voters. On January 6, 1919, they went to the polls and by a 3:2 margin selected Public Square as the site for the development. In doing so the voters set into motion the Cleveland Union Terminal Project, which over the next 15 years would significantly alter the city’s skyline and create for Cleveland its most famous landmark. Simultaneously, however, their decision left the long-time civic vision to complete the Mall Plan unfinished. Over the 100-plus years since the Group Plan was first presented, Clevelanders have been vocal in demanding that the basic mall layout not be compromised. That issue has bedeviled plans over the years, and it remains a challenge to the present time.

Voters, politicians, and a subway

The first plan for a downtown subway was the result of the dramatic increase in passengers on the surface lines of the Cleveland railway company. Between 1910 and 1920, annual passenger totals climbed from just over 225,000,000 to nearly 451,000,000. Downtown Cleveland had become the place to shop, not just for inhabitants of the city, but for the entire Northeastern Ohio region. Streetcar traffic and the increasing number of automobiles, which numbered over 40,000 by 1920, were choking the downtown street network.

The Detroit-Superior Bridge (now the Veterans Memorial Bridge) opened in November 1917. It had been designed with two decks, the top one for pedestrians, bicycles, and automobiles, and the lower deck for streetcars. The separate right of way for the streetcars was intended to speed their way across the Cuyahoga River, and suggested to city planners additional transportation advantages that could come from a subway.

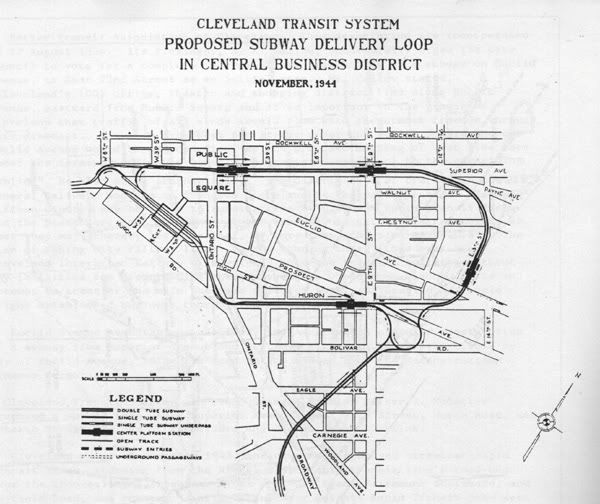

The plan called for modern streetcars operating over the outer portions of existing routes, then joining traffic-segregated rapid transit rights of way, before dropping into a downtown subway loop. It was a plan similar to those then operating in Boston and Philadelphia (and which continue to the present time in those cities). The down- town subway loop would have been built beneath Huron Road, East 13th Street, Superior Avenue, and West Third Street to Cleveland Union Terminal. It would have connected the uptown shopping district (Halle’s and Sterling’s, Bonwit Teller) with the stores clustered near Public Square (Bailey’s, Higbee’s, and May’s).

In 1945 the city of Cleveland hired a Chicago consultant, Deleuw, Cather and Company, to review the modernization plans. Its report held that the city only needed a single rapid transit line, rather than several, but it supported the idea of a downtown subway. Plans for the rapid transit line went forward, and today’s red line, the portion from Windermere to West 117th street (later extended to West 143rd street and later to Cleveland Hopkins International Airport) was the result. It opened in 1955. The subway portion of the plan, for which a $35 million bond issue had been approved by voters in November 1953, was in the planning stages.

Highway improvements were also getting increased attention. In 1940 county voters approved a bond issue to finance the next stages in highway improvements. Automobile registration in the county had skyrocketed to 350,000, a more than eight-fold increase in just 20 years. Motorists faced daily gridlock on the existing street network. Limited access freeways were seen as the answer, and work began on the Willow Freeway (today’s I–77).

In 1944 a comprehensive plan for future freeway development was published. it called for “Outerbelt” freeways, serving the perimeter of Cuyahoga County, as well as radial freeways with downtown as their axis.

Substantial progress of translating this system of limited-access roads, however, did not occur until after 1956 when Congress passed of the Federal-aid Highway act to establish the interstate system. The first portion of a revised highway plan, generally designed along the lines of the 1944 version, was the Innerbelt Freeway. Its first segment opened to traffic in 1959.

The plan for the downtown subway became the focus of heated debate. While its advocates cited the need for a rapid transit system with more than one downtown station, the plan was vigorously opposed by Cuyahoga County engineer Albert Porter. He contended that population was shifting to the suburbs, public transit ridership was falling (by 1959, from its peak in 1946, 250 million riders since its peak in 1946), and that downtown was losing its pre-eminence as a destination. Ultimately, his arguments prevailed, and in December 1959, the county commissioners decided not to issue the subway bonds.

At the same time, taking advantage of the federal support for building the interstate system of Highways, local planners moved forward. Beginning in 1956 with the downtown Innerbelt, the road-building project eventually resulted in 116 miles of super-highway within Cuyahoga County.

Beginning in 1960 Cleveland Transit System officials proposed a series of six new rapid transit lines that would radiate from downtown to all corners of the county. It was their belief such an investment was the only way to mitigate the pull of decentralization. None of these was ever built.

The automobile had become the highest priority in transportation planning, and it would remain in that position right up to the present time.

Regionalization begins to take hold

In 1950, the city of Cleveland reached its all-time peak in population, with 914,808 city dwellers. Cuyahoga County’s population also continued to grow, reaching 1,389,582; the city’s population accounted for 66% of the county total.

But then things began to change. At first the loss of city population was modest. Between 1950 and 1960, Cleveland lost just over 4% of its residents. By 1970 the out migration to the suburbs had accelerated, the city losing another 14% of its citizens, and for the first time more people were living in the suburbs than in the central city. Cuyahoga County’s population had climbed to 1,720,835.

During the 1970s the trend became even more severe. Cleveland lost another 177,057 residents during that decade, and for the first time the county also saw its numbers shrink. Besides the loss in numbers from Cleveland itself, the suburbs had also begun to lost numbers. Altogether, the county’s population fell by 222,435 to a total of 1,498,400.

Not only had the population begun to move ever farther from the mother city, but Cleveland’s strength as an industrial and manufacturing was also being eroded, as plants and jobs moved to the southern states and out of the country as well. These demographic changes translated into a dollar drain, and the city could no longer afford to operate elements of its infrastructure. The response was recognition that the burden of supporting urban life had to be spread more broadly.

One of the first steps towards regionalization came in 1968 with the establishment of the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA). The agency was charged with establishing priorities for future transportation and water quality projects.

Soon came a series of other transfers, responsibility being shifted from the city to county and/or regional bodies. In 1968 the commercial waterfront became the responsibility of the newly established Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority. In 1970 the Metroparks assumed control of the Cleveland Zoo. The Cleveland sewer system was turned over to the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District in 1972. In 1975, the Cleveland Transit System, deeply in debt and bleeding ridership, was turned over to the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority. And then in 1978 the state of Ohio established the Cleveland Lakefront State Park to manage the city’s lakefront park properties.

In the course of a decade the city of Cleveland was able to shed financial responsibility for all of these assets, and turn them over to a countywide authority for their future operation. It was a real start towards regionalization, but that effort seemed to stop at the county’s borders.

In transportation, for example, the new Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority was authorized to serve the broader Northeast Ohio region, but doing so would require adjacent counties seeking the service to support it financially. None of the neighboring counties chose to do so.

The 1980 census revealed a drastic drop in the city’s population, to 573,822. For the first time Cuyahoga County also showed a loss, with some 220,000 fewer residents than just one decade earlier. The steps taken towards regionalization during the 1970s were proving to be only a temporary solution. A broader support network was needed.

It took some time to develop a plan that would advance the regionalization effort. In 2004 the Greater Cleveland Partnership (formerly the Greater Cleveland Growth Association and itself a product of merger among area advocacy and development groups) launched a three-year plan to “mobilize private-sector leadership, expertise and resources to create jobs and leverage investment to improve the economic vitality of the region.” One component of the plan resulted in the major chambers of commerce in the region joining to form Team NEO, a business-development agent for 16 Northeast Ohio counties. Another was the formation of the Cleveland Plus marketing alliance to coordinate a general marketing strategy and program for the region. These programs helped not only to promote the region to the rest of the country, but they also served to raise the consciousness of the local population (about 4,000,000 in the 16-county area) of the importance of working together to advance the region. One manifestation of this local consciousness was the approval by Cuyahoga county voters in November 2009 of a new charter for more effective county government. The resulting vision from these efforts is essentially threefold: 1) sustainable economic development, 2) population stabilization, and 3) quality of life across the region.

These are the 21st-century challenges that now face Northeast Ohio, and a broad consensus has been achieved about them.

NOACA, the agency responsible for local transportation planning, in its Connections 2030: A Framework for the 2030 Transportation System, reflects this consensus. in particular, NOACA has identified revitalization of the region’s urban core as a primary focus. It has also produced a goal to “establish a more balanced transportation system which enhances modal choices by prioritizing goods movement, transit, pedestrian and bicycle travel instead of just single occupancy vehicle movement and highways.”

The first half of the 20th century emphasized improvements in the public transit system. the second half of the century was focused on the automobile. Public policy at the start of the 21st century endorses yet a third vision.

New Challenges for Transportation in Greater Cleveland

Many ideas have been advanced to achieve the goals to achieve the three fold goals for revitalizing Northeast Ohio. as with most ideas of this kind, there are both advocates and critics, not mention a plethora of obstacles that must be faced and surmounted to bring these plans to life. east of them tackle the challenge from a different perspective.

Highway planning

Three highway projects are on the planning frontline in 2010. Two represent a reconstruction of existing highways and the other a return to a long dormant idea.

The most costly of these projects involves the rebuilding of the Innerbelt Freeway, a task made necessary by the deterioration which the fifty-year-old downtown bypass route is experiencing. The project calls for a second bridge to be built across the Cuyahoga Valley. When that project is completed the existing bridge will be completely rebuilt. The project also involves the re-engineering of the lakefront “Dead Man’s” Curve, as well as reducing the number of on/off ramps between the curve and the bridge.

As is typically true of most Cleveland projects, this one has experienced considerable public criticism, centering around bridge design and the impact on downtown venues from fewer access points.

The second highway project involves rebuilding the West Shoreway (also designated as Ohio Route 2). The reconfiguration would cover the highway from Baltic Avenue on the west side to downtown. The plan envisions changing the limited-access, 50-mph freeway into a tree-lined boulevard with a 35-mph speed limit. It would add three entrance/exit points along the route, thus making Edgewater Park and adjacent properties more accessible to the west side neighborhoods that flank the highway. Such an improvement is seen as enhancing the prospects for the continued revitalization of the Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood. The project is seen as contributing to the goal of improved quality of life for city dwellers.

The third project carries the name Opportunity Corridor. It is a 2.75-mile boulevard running from the eastern terminus of interstate 490 at East 55th Street east to East 105th street at the edge of the city’s University Circle medical, educational, and cultural hub. NOACA has given the project a high priority.

The current plan represents a significant reconfiguration of the long-abandoned Clark Freeway which would also have traveled east from East 55th street, but its path would have carried it through Shaker Heights, significantly disrupting both residential and park settings. It was vetoed by the residents of that suburb.

The new routing would have minimal impact upon residential neighborhoods, running through mostly abandoned industrial sites and along the rapid transit right of way that traverses the area. The highway is seen as a significant economic development tool, opening up some 350 empty acres to new industrial construction and the attendant jobs that these would generate. The plan also addresses quality of life issues, making the University Circle attractions more directly accessible from the area’s existing interstate highway system.

The Port of Cleveland

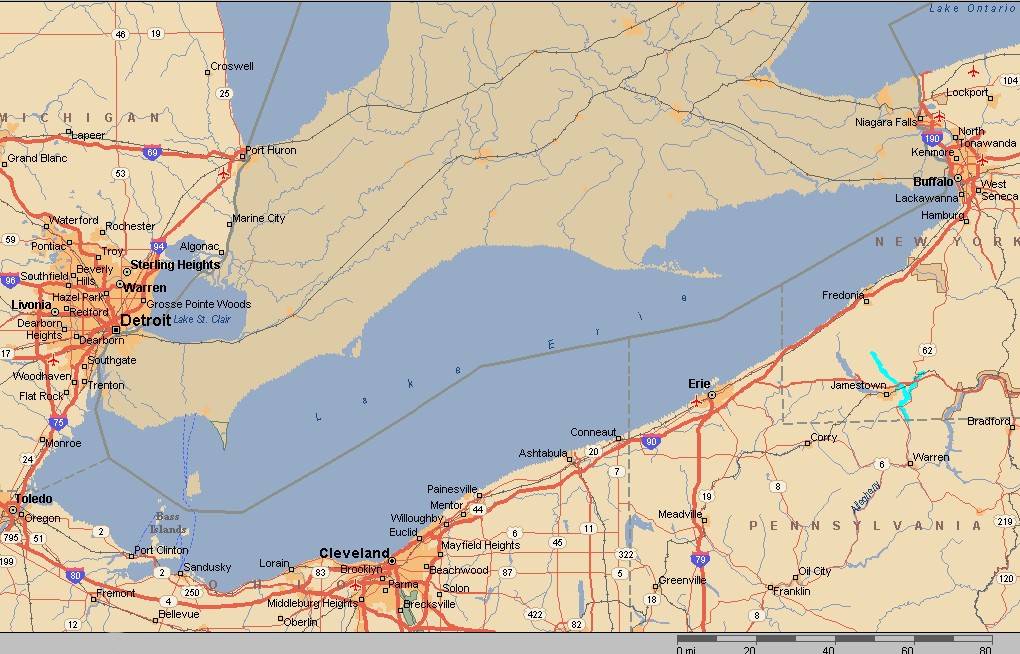

Cleveland’s very existence is due to its geographic location at the confluence of the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie. Cleveland was founded in an era when water transportation was the primary means for moving freight. The Port of Cleveland has continued to be an important part of the region’s commercial network.

As the regional priorities have changed, however, a growing consensus has emerged that the location of the port, on downtown lake front land, may not be the most promising future use of that area. A 2004 City of Cleveland planning document called for major redevelopment of the downtown waterfront for residential and recreational use.

A preliminary proposal to address this interest suggested relocating the port facilities farther east to a newly created dike area near East 55th Street. The cost of such a move, the time required for its implementation, and changes in personnel on the Port Authority board and its management team, however, spelled the end of active consideration for the idea

Instead, at least in the short term, port officials are looking more closely at underutilized port land west of the Cuyahoga River, and they are pursuing plans to increase the capacity of the port to handle container shipping via Montreal and the St. Lawrence Seaway. Such a development is seen as attractive to international shippers, considering the congested nature of ports on the eastern seaboard. Another aspect of this plan would envision facilities to handle truck traffic ferried across Lake Erie from Canada.

An urgent problem faced by the community is the need to build a new dike to handle dredging from the Cuyahoga River. The current dike at the east end of Burke Lakefront Airport will have reached capacity by 2014, and the port needs to determine a new site for the more than 300,000 cubic yards of sediment removed from the river and harbor each year.

Passenger Railroad Service

Passenger rail service for Clevelanders is limited. As of 2011, Amtrak trains connect Cleveland with Chicago, the Lake Shore Limited and the Capitol Limited. The eastern portion of the Capitol Limited route connects Cleveland to Washington, D.C., and the Lake Shore Limited connects with New York city and Boston.

In 2009, the federal government’s stimulus plan authorized a $400 million plan to connect Cleveland with Columbus and with Cincinnati, via Dayton. The so-called 3C route was warmly greeted by then Governor Ted Strickland, although critics cited limitations to its appeal for travelers. Because the plan would have had passenger trains sharing existing track with freight trains (although some of the route would have been improved by additional passing sidings), the passenger service’s top speed would be limited by existing safety regulations. Critics felt that while rail service would be more comfortable than intercity bus travel, its inferior schedule speed would be a deterrent to broad acceptance.

Newly elected Governor John Kasich rejected the 3C proposal in one of his first acts upon taking office in 2011.

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority has also studied the development of a commuter rail network. In its Transit 2025 document, it offers the possibility of developing rail connections between Cleveland and Painesville, Aurora, Akron, Lorain, Elyria. A rail link beyond Lorain to Sandusky via the existing Nickel Plate corridor has more recently been given a closer look, but any prospects for such a line carry a completion date at least ten years into the future.

Airport Decisions

Cuyahoga County has three airports: Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, and the smaller Burke Lakefront Airport and Cuyahoga County Airport. The question has been rather continuously raised about whether both of the smaller airports are really needed. Burke Airport was built in 1947 on the site of a lakefront garbage burning site. Cuyahoga County Airport opened in 1950 in suburban Richmond Heights.

The two smaller airports serve to siphon smaller private and corporate aircraft from Hopkins, thus relieving congestion there. In light of the fact that neither smaller airport has achieved the promised benefit that was forecast for them, should operations be consolidated at one of them?

If Burke were to be closed, 450 acres of valuable lakefront land would be opened for commercial and residential redevelopment. Its central location, however, in comparison to Cuyahoga’s location 11 miles east of downtown, makes Burke a more appealing to the business traveler.

While planners suggest changes in the current status of the two smaller airports, officials continue efforts to improve the infrastructure and operational features of both facilities. A decision about the future does not appear imminent.

Pondering Past and Present Policy

Past Ponderables

1. The first of the six downtown department stores closed in late 1961. If the downtown circulator subway (rejected by the commissioners in 1959) had been built, would it have allowed downtown to remain a vibrant shopping district, or might it have slowed the decline, or was the eventual death of the Euclid avenue shopping zone inevitable?

2. Would the proposed development of a more extensive rapid transit system, connecting inner and outer ring suburbs to downtown, succeeded in offsetting the pull of outmigration from the city; might it have mitigated the appeal for the suburban office parks that sprang up in the suburbs?

3. Construction of the interstate highway system in the county made cross-county travel much easier for motorists. the highways, however, required a right of way that resulted in the demolition of hundreds of homes in Cleveland and which often severed neighborhoods. to what extent was the highway construction program the cause for accelerating the loss of city population and of increasing urban blight?

Present Ponderables

1. Have such organizations as NOACA, Team NEO, and Cleveland Plus correctly identified the priorities which are most critical to the revitalization of Cleveland and of Northeast Ohio? Are there other priorities that should be added to the list or which should replace the current emphases?

2. Are the projects being proposed as addressing the region’s most compelling needs well chosen to meet the established priorities? are these likely to achieve the goals toward which they are pointed?

3. What data can be summoned to either support or criticize plans for a) highway changes; or b) commuter or intercity railroad development, or c) port relocation, or d) airport consolidation?

So, too, the progenitors of Cleveland’s diverse button-box accordion and polka music, with Polish, Italian, Czech, German, and Croatian styles, but whose most important heir was

So, too, the progenitors of Cleveland’s diverse button-box accordion and polka music, with Polish, Italian, Czech, German, and Croatian styles, but whose most important heir was  Adding to the diversity were the early

Adding to the diversity were the early  Then in 1990, newly elected

Then in 1990, newly elected

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced

n’t agree more. Akers was at Cleveland City Hall almost a generation before Warren—now Mayor Frank Jackson’s regional economic development czar— arrived. He was Ralph Perk’s chief of staff in the 1970s. Eventually, he became mayor of Pepper Pike, a bedroom community that in 1924 was carved out what was once Orange Township. As a leader of the Cuyahoga County Mayors and Managers Association, Akers has spent more than a decade trying to convince other suburban officials that they need a new model of cooperation—one premised on two central ideas: one, that every community in Greater Cleveland will sink or swim together. And two, that Cleveland’s fate will dictate everyone else’s. That’s led Akers to embrace Hudson mayor

n’t agree more. Akers was at Cleveland City Hall almost a generation before Warren—now Mayor Frank Jackson’s regional economic development czar— arrived. He was Ralph Perk’s chief of staff in the 1970s. Eventually, he became mayor of Pepper Pike, a bedroom community that in 1924 was carved out what was once Orange Township. As a leader of the Cuyahoga County Mayors and Managers Association, Akers has spent more than a decade trying to convince other suburban officials that they need a new model of cooperation—one premised on two central ideas: one, that every community in Greater Cleveland will sink or swim together. And two, that Cleveland’s fate will dictate everyone else’s. That’s led Akers to embrace Hudson mayor

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.