From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

ARCHITECTURE. Cleveland’s innovations in certain areas of architectural planning have displayed a progressiveness and vision matched by few other cities. The 1903 Group Plan, which produced widespread national admiration at the time, is only one example. In the 1920s, the plan of the CLEVELAND UNION TERMINAL complex anticipated many of the features of Rockefeller Center. Greater Cleveland also developed the first comprehensive modern building code (1904), the first industrial research park (NELA PARK, 1911), and the most spectacular realization of the garden city suburb idea inSHAKER HEIGHTS Moreover, Cleveland is not without its individual architectural landmarks that have no peer anywhere, the most notable being theARCADE of 1890.

Architectural design in Cleveland during most of its history was typical of that in any growing midwestern commercial and industrial city. The building needs for various uses–domestic, commercial, religious, social, industrial, and so on–were common. The same is true of the styles used to clothe these uses; styles followed the general chronological development of those in the rest of the nation. The design of buildings was determined less by any discernible architectural philosophy than by the function or symbolism of the building, the wishes of the builder, the type of site or amount of money available, and the dictates of fashion. Because of the demand, the city attracted numerous fine architects, who generally produced buildings at a very high level of quality, though Cleveland is not known as the home of prophetic architects of national reputation.

At the time of Cleveland’s beginnings in the early 19th century, there was no profession of architecture in the modern sense. The designer of buildings was sometimes a gentleman-scholar but more often a master builder in the late-18th-century tradition. The first master builder practicing in Cleveland who called himself “architect” was JONATHAN GOLDSMITH† (1783-1847) of Painesville, who built at least 10 houses on Euclid Ave. in the 1820s and 1830s. The most notable were the Federal-style Judge Samuel Cowles mansion (1834) and the Greek Revival Truman Handy mansion (1837). The modern profession of architecture began in the 1840s, and the individual private practice, performing most of the services of the modern architect, was established in Cleveland before the Civil War. Goldsmith’s son-in-law CHAS. W. HEARD† (1806-76) was the most important architect from 1845 until his death. From 1849-59 he worked in partnership with SIMEON C. PORTER† (1807-71) from Hudson, OH. Heard and Porter designed predominantly in the Romanesque Revival style (Old Stone Church, 1855). They introduced the use of cast-iron columns in Cleveland in the mid-1850s. Heard designed the Case Block (distinct fromCASE HALL), rented and known as city hall, Cleveland’s greatest Second Empire building, in 1875.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Cleveland’s most magnificent architectural ensemble was found on EUCLID AVE., lined with the fashionable mansions of wealthy executives in shipping, iron and steel, oil, electricity, and railroads. The fine residential stretch between E. 12th and E. 40th streets was known as “Millionaires Row”; Clevelanders and many visitors called it “the most beautiful street in the world.” Mansions remaining from the Greek Revival period, together with Gothic Revival and Tuscan villas from the 1850s and 1860s, stood side by side with great Romanesque Revival stone residences and eclectic houses in the Victorian Gothic, Renaissance, Queen Anne, and Neoclassic styles. The residences were designed both by Cleveland architects such as LEVI T. SCOFIELD†, CHAS. F. SCHWEINFURTH†, and GEO. H. SMITH† and by out-of-town architects, including Peabody & Stearns, Richard M. Hunt, and Stanford White. Euclid Ave. remained fashionable until after the turn of the century, but virtually all of “Millionaires Row” was destroyed in the years around World War II.

At the same time, Cleveland participated in the revolution in commercial architecture that evolved simultaneously in Chicago, New York, and other large commercial cities, and which was characterized by 1) a concern for fireproof construction, 2) the provision of lighter and more open structure, and 3) the evolution of iron and steel skeletal construction. The foremost exponents of this development in Cleveland were FRANK E. CUDELL† (1844-1916) andJOHN N. RICHARDSON† (1837-1902), who produced a remarkable series of progressively lighter and more open structures between 1882-89–the Geo. Worthington Bldg., the Root & McBride-Bradley Bldg., and the PERRY-PAYNE BUILDING The first in Cleveland to utilize iron columns throughout all 8 stories, the latter contained an interior light court that attracted visitors from a considerable distance. The Chicago School of commercial building was actually represented by 3 buildings of Burnham & Root–the Society for Savings (1890), whose masonry load-bearing walls enclose an iron skeleton, and whose lobby is an unusually fine example of decorative art in the

Wm. Morris tradition; the WESTERN RESERVE BUILDING (1891), a building of similar structure built on an unusual triangular site; and theCUYAHOGA BUILDING (1893; demolished 1982), the first building in Cleveland with a complete steel frame.

The development of skeletal structure and the interior light court reached a climax in Cleveland with the construction of the ARCADE. Opened in 1890, the Arcade is an architectural landmark that has remained without peer for more than 100 years. Combining features of the light court and a commercial shopping street, the “bazaar” of stores and offices was built by a company whose officers included STEPHEN V. HARKNESS† of Standard Oil andCHAS. F. BRUSH†. The architects were JOHN EISENMANN† and Geo. H. Smith. The 300′ long iron-and-glass arcade of 5 stories is surrounded by railed balconies and connects two 9-story office buildings designed in the Romanesque style. Because of the differences in grade, there are main floors on both the Euclid Ave. and Superior Ave. levels. The skeletal structure of the Arcade consists of iron columns and oak, wrought iron, and steel beams. The roof trusses were of a new type; since no local builder would bid on the construction, the work was done by the Detroit Bridge Co. The central well of the Arcade, with its dramatic open space and natural light, is the most impressive interior in the city, and its renown is international.

Other architects active in the last quarter of the century were ANDREW MITERMILER†, planner of breweries, business blocks, and social halls; JOSEPH IRELAND†, architect to AMASA STONE† and DANIEL P. EELLS†; Levi Scofield, designer of Cleveland’s most important monument, the SOLDIERS’ AND SAILORS’ MONUMENT (1894); and COBURN & BARNUM, whose major works were institutional and business buildings. By 1890 36 architects were listed in the city directory, and in the same year the Cleveland chapter of the AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS, CLEVELAND CHAPTER was formed. To design important Cleveland buildings in the 1890s, however, many clients sought architects of national reputation, among them Burnham & Root, Richard M. Hunt, Henry Ives Cobb, Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, Geo. B. Post, Peabody & Stearns, and Geo. W. Keller. After the turn of the century, these included Stanford White and Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson.

When the profound change from Victorian revivalism to classicism took place in the 1890s, Cleveland architects responded with characteristic adaptability. Such architects as Geo. H. Smith, LEHMAN AND SCHMITT, GEO. F. HAMMOND†, and KNOX & ELLIOT began careers in the Richardsonian Romanesque and other revival styles and later were able to design tall office buildings and Beaux-Arts classical monuments with equal facility. One architect of this generation, CHAS. F. SCHWEINFURTH† (1856-1919), was the first Cleveland architect to rank with those of national stature. Trained in New York, he came to Cleveland to design mansions, institutional buildings, and churches for the wealthy, especially in association with Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Mather. His early work was in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, but his masterpiece is generally agreed to be the Gothic TRINITY CATHEDRAL(1901-07).

The dominance of the classic revival was epitomized by the Group Plan of 1903, whose significance was immediately recognized across the country. The plan evolved as a result of the conception that newly planned federal, county, and city buildings could be placed in a monumental grouping. The Group Plan Commission consisted of Daniel H. Burnham, John M. Carrere, and Arnold W. Brunner. Uniformity of architectural character and building height was recommended, and the Beaux-Arts classical style was followed. The MALL, which is the center of the plan, was finally completed in 1936, and the major buildings include the Federal Courthouse (1910), CUYAHOGA COUNTY COURTHOUSE (1912), CLEVELAND CITY HALL (1916), PUBLIC AUDITORIUM (1922), CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY (1925), and Board of Education Bldg. (1930). As an example of city planning inspired by the City Beautiful movement and specifically by the precedent of the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Cleveland’s Group Plan brought the city a national reputation for progressive municipal

vision.

A few Cleveland architects studied at the Beaux-Arts in Paris and brought its teachings with them, the most notable being J. MILTON DYER† (1870-1957), architect of the city hall. By the 20th century, the first generation of architects trained in an American architectural school was beginning to practice. In 1921 a group of architects established the Cleveland School of Architecture, with ABRAM GARFIELD† as the first president. The school was affiliated with Western Reserve Univ. in 1929. It later became a department of WRU (1952) and continued to operate until it was discontinued in 1972. Many architects were attracted to Cleveland by the opportunities to build in the growing and wealthy industrial city. The development of well-to-do suburban enclaves inLAKEWOOD, BRATENAHL, and the Heights between 1895-1939 fostered a climate in which eclectic residential architects flourished. Among the finest were Meade & Hamilton, Abram Garfield, PHILLIP SMALL†, CHAS. SCHNEIDER†, FREDERIC W. STRIEBINGER†, CLARENCE MACK†, J. W. C. CORBUSIER†, ANTONIO DI NARDO†, and Munroe Copper.

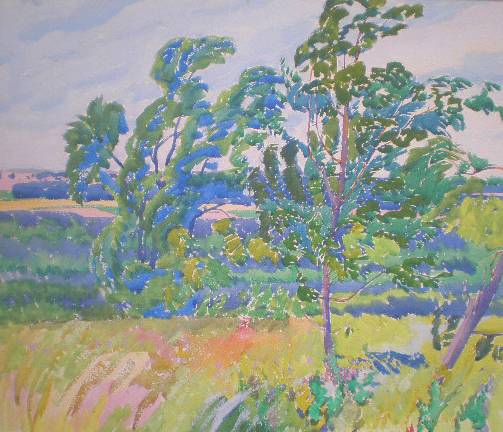

The development of SHAKER HEIGHTS (1906-30) was probably the most spectacular embodiment of the suburban “garden city” idea in America. The subdivision was laid out so that curving roadways, determined as much by the topography of the land as by the desire for informality, replaced the grid layout of city streets. The apparently aimless meandering of the roads was actually calculated to provide access to the main arteries, as well as to create the best advantages for beautiful and livable home sites. Certain locations were reserved for the commercial areas, and lots were donated for schools and churches.

The homes of Shaker Hts. could be built for a wide range of prices, and there were neighborhoods of diverse character, from mansions to more humble homes. The architecture of the houses of the 1920s held few surprises; eclecticism was the accepted manner. The architects turned to styles that had developed satisfying and comfortable forms of domestic architecture, including American Colonial and English Manor (either Adam or Georgian), French, Italian, Elizabethan, Spanish, or Cotswold. But the similar plans and common scale, differentiated mainly in detail, resulted in familiar streets where the different styles stand side by side without jarring in the least.

The consistency of the domestic vision in the planned suburb was remarkable. Churches were designed to relate to the domestic architecture, the two favorite styles being American Colonial and English Gothic. Schools, stores, libraries, hospitals, fire stations, and even the gasoline stations were designed in the Georgian and Tudor idioms. In 1927-29 the planned suburban shopping center at Shaker Square was built in the Georgian Colonial style. The plan of the square has been compared to a New England village green, but it owes a great deal to the concepts of mid-18th-century Neoclassic town planning in Europe; it has been suggested that the octagonal form of the square and its buildings was patterned after the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen. SHAKER SQUARE illustrates the continuing dependence on European models, combined with the expected references to American Georgian domestic building. It is also unusual in its integration of the rapid-transit line, which made the development of suburban Shaker Hts. possible.

The first 3 decades of the 20th century also saw a greatly increased demand for much larger and more formal private, institutional, and public buildings. Two architectural firms dominated the field–HUBBELL & BENES, architects of the WEST SIDE MARKET, the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, and the Ohio Bell Telephone Bldg., and WALKER AND WEEKS, architects of the FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF CLEVELAND, Public Auditorium, the Cleveland Public Library, and SEVERANCE HALL. However, two of the largest such projects of the period, the HUNTINGTON BUILDING and the Union Terminal Group, were entrusted to the Chicago firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White.

The Terminal Group (1922-31), an architectural complex that became the symbol of Cleveland, consisted originally of 7 buildings occupying 17 acres. The group was notable for the development of commercial air rights over the station; all of the passenger facilities were below the street level. The arched portico on the PUBLIC SQUARE led to the Terminal Tower lobby and to ramps going to the station concourse level. The Hotel Cleveland (1918) was incorporated into the group and balanced by Higbee’s department store (1931). The Terminal Group may be compared with Rockefeller Center, which it predated by several years, in size, multipurpose use, and the incorporation of connecting underground concourses and an indoor parking garage. The 52-story Beaux-Arts-style tower, second-tallest in the world in 1928, is crowned by a classical spire, probably based on the New York Municipal Bldg. of 1913. Sometimes criticized as conservative in style, the Terminal Tower forms a focal point for the Public Square and the radiating avenues of Cleveland’s street plan, expressing the enterprise of the VAN SWERINGEN† brothers who built it. The Builders’ Exchange (Guildhall), Medical Arts (Republic), and Midland buildings, also planned by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, were designed in the modernistic style of 1929-30; their Art Deco lobbies were destroyed in 1981. The last building in the original group, the U.S. Post Office, was completed in 1934.

The Depression era saw profound effects in architecture. Apart from the general decline in building and the consequent attrition in the number of practicing architects, the most important was the arrival of modernism under the influence of the European International style, which was most apparent in the design of federal public works. The first 3 public housing projects authorized and begun by the Public Works Admin. were built in Cleveland in 1935-37. They were the Cedar-Central apartments planned by WALTER MCCORNACK†, Outhwaite homes by Maier, Walsh & Barrett, and LAKEVIEW TERRACE by Weinberg, Conrad & Teare. Lakeview Terrace is especially notable because of its adaptation to a difficult sloping site, and it appeared in international publications as a landmark in public housing. The simple design of the building units was clearly influenced by the European precedent of the International style. Other architects who adopted the new style with intelligence and vigor were J. Milton Dyer, HAROLD B. BURDICK†, CARL BACON ROWLEY†, J. Byers Hays, and Antonio di Nardo. The GREAT LAKES EXPOSITION in 1936 provided an opportunity for the display of the simple geometric forms of modernism, but the general acceptance of the style did not occur until after World War II.

The architecture of the postwar era is difficult to assess objectively from a recent perspective. New construction in Cleveland may have been more conservative in style and direction than at any other period in its history. Buildings continued to be built in traditional forms, as well as in the rectangular geometry of the assimilated International style. Many major projects were still awarded to nationally famous architects. Greater Cleveland saw structures designed by two of the old masters of modern architecture, Eric Mendelsohn and Walter Gropius. In the 1950s and 1960s, Cleveland firms such as Outcalt, Guenther & Associates filled the need for comprehensive planning on such projects as the Cleveland Hopkins Airport Terminal and master plans forCUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY While the individual practice continued, a new type of complex design organization that could plan everything from a single structure to a megalopolitan transit system was typified by Dalton-Dalton-Little-Newport. TheERIEVIEW urban-renewal plan of 1960 was one of the most ambitious undertaken under the Federal Urban Redevelopment program. The clearance of nearly 100 acres between E. 6th and E. 14th streets, Chester Ave. and the lakefront provided sites for the building of new public, commercial, and apartment structures. The centerpiece of the plan was Erieview Tower (1964), designed by Harrison & Abramovitz. A new commercial and financial center developed that extended from Erieview to Euclid and E. 9th; from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, no fewer than 12 new office buildings were erected in and around the area. Virtually all of the new buildings represented variations on the formula of the late modern glass and metal skyscraper. The architects included Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Chas. Luckman, Marcel Breuer, and local Cleveland design firms.

Though it lies just over the Summit County line, the music pavilion of the Blossom Music Center (1968) deserves mention as the product of a Cleveland architect, Peter van Dijk, for a Cleveland institution, the CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA. The Ohio Section of the AIA in 1992 voted the dramatic clam-shaped shelter a 25 Year Building Award as a structure of lasting importance.

The most significant achievements in Cleveland architecture have been in large-scale planning–the Group Plan, the Terminal complex, Shaker Hts.,PUBLIC HOUSING, and urban renewal. Chronologically, architectural design has often lagged behind national developments, and its general standard has been typical of that in cities of the same size. Individual buildings of every period rival buildings anywhere in quality–the Arcade, the Terminal Tower, the Society Bank, the Rockefeller Bldg., the motion picture palaces, and many churches. Several Cleveland architects, such as Chas. Schweinfurth and the firm of Walker & Weeks, achieved regional if not national reputations, and they will doubtless be more widely recognized when their work is fully documented. In conclusion, the architecture of Cleveland constitutes a representative index of the physical development and the taste of a large midwestern industrial and commercial city throughout its 19th- and 20th-century history.

Eric Johannesen (dec.)

Chapman, Edmund H. Cleveland: Village to Metropolis (1964).

Johannesen, Eric. Cleveland Architecture, 1876-1976 (1979).