Florence Allen 1921 KSU

Florence Allen 1921 KSU

FLORENCE E. ALLEN,

CLEVELAND’S MOST FAMOUS WOMAN

ALMOST NO CLEVELANDERS TODAY HAVE HEARD OF

By Marian J. Morton

The pdf is here

When the Plain Dealer’s Andrea Simakis discovered “the unstoppable Judge Florence Allen,” she marveled over Allen’s path-breaking career, her intellect, her perseverance, her “moxie.” And yet, Simakis mused, “… I had never heard of her… Neither had a lot of women I know.” [1] But for much of Allen’s lifetime (1884-1966), almost everyone in Cleveland – at least everyone who read the newspapers – had heard of her. She was Cleveland’s most famous woman,[2] not just because she was the “first lady of the law,”[3] not just because this local girl made very, very good, but because Allen herself made it happen. A performer by both nature and nurture, Allen loved being center stage. She gave hundreds of speeches -on soapboxes, street corners, luncheons, and lecture halls – on topics ranging from opera to woman suffrage to outlawing war; she faced down hecklers and anti-suffragists; she led and marched in parades. These set the stage for successful runs for municipal judge and the Ohio Supreme Court and less successful runs for the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate and a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court. Fiercely ambitious, she cultivated political allies from local precinct captains to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt; fiercely competitive, she relished the challenges of being the first woman in a male role. Her reward: fame, although fleeting.

FIRST ACTS: AMATEUR THEATER

One of Allen’s earliest memories was of her five-year-old self on a make-shift stage, dressed in costume, like her older sisters, in a performance that celebrated her father’s birthday. Allen recited the Greek alphabet, which he had taught her. [4]

The family was living in Utah, where her father, Clarence Emil Allen, had gone to recover from tuberculosis. He was a graduate of Western Reserve College in Hudson, then became head of Western Reserve Academy, and then taught classics at the college until his health gave out. His wife, Corinne Tuckerman Allen, and two small daughters, Esther and Helen, followed him to Salt Lake City.

He quickly entered public life. He studied law, was admitted to the bar (no law school necessary in those days), and became county clerk. He was elected to the territorial legislature, and when Utah became a state in 1895, he became one of its first elected representatives to the U.S. House of Representatives. He served only one term, and after his return from Washington D.C., made his living as an assayer for one of the mines of Liberty Holden, owner of the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Corinne Allen “was always immersed in some public undertaking,” her daughter recalled.[5] Corinne had been admitted to the first class at Smith College in 1875, one of a tiny handful of women who attended college in the 1870s. Although she dropped out of college to marry Clarence, she believed that her privileged education gave her special responsibilities to her community. Florence was born in Utah, and Elizabeth, Clarence Emil Jr., and John followed. Utah women had been enfranchised by the Utah territorial legislature in 1870, disenfranchised by Congress in 1887 in a dispute over the legality of polygamy, but continued to play public roles. An energetic participant in the woman’s club movement of the late nineteenth century, Corinne joined local, state, and national women’s clubs and helped found the Mothers’ Congress, later the P.T.A. She was a vocal opponent of the Mormon practice of polygamy. Corinne became an organizer in 1900 for Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan.[6]

Florence Allen attended high school in Salt Lake City, where she was most inspired by her piano teacher, and in 1900, at age 16, she entered the Women’s College of Western Reserve University. Although she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, she later recalled, “I do not seem to have been greatly interested in any special branch of learning,” except piano, which she practiced for hours. She found time for politics, however, and was elected freshman class president.[7] She loved going to local operas, stage productions, and concerts; her college scrapbooks are full of playbills with lively comments in the margins. [8] She also greatly enjoyed “the dramatics that we produced on the campus,” proud of her role in which “I was stout, vigorous, shook my cane and swore enthusiastically.” [9] No male actors being available, she – with a strong voice – also played the king in a Hindu play: “ I sweltered in the royal purple robe.” [10]These college theatrics were dress rehearsals for performances in her judicial robes.

Allen was tall, sturdily built (she struggled with her weight all her life), with regular features and a broad forehead. Until the 1920s, she wore her hair long and piled on top of her head. She was handsome, not conventionally pretty. [11] She had a commanding presence, appreciated and applauded by audiences and supporters. By her own account – and other’s -, she had little fashion sense and recalled more than one occasion when friends at the last-minute scrambled to provide something appropriately feminine for her to wear for a public appearance. [12]

After graduation in 1904, Allen accompanied her mother to Berlin, where Corinne had been asked to speak on polygamy to the International Council of Women. Florence studied piano but decided that she lacked the talent to make her living as a musical performer. Instead, she became a music critic, which provided her with an entry into her public life in Cleveland when she returned in 1906. She landed a job at Laurel School, a private girls’ school, where she directed the plays, played piano for chapel every morning, and taught “Greek, German, geography, grammar, and American history.” [13]

More important, she became the music critic for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. She reviewed concerts, operas, orchestras, and solo performers weekly and sometimes more often. To readers, the byline, “By Florence Allen,” became associated with social respectability and professional integrity.

But she didn’t want to teach high school girls or write music reviews forever. At the suggestion of one of her teachers at Western Reserve University, she studied for a master’s in political science and decided to go to law school. Law was very much a male field, and the new requirement of law school made it even more difficult for women. Western Reserve University Law School, for example, did not accept women, so Allen went first to the University of Chicago and then to New York University. She graduated second in her class.

In New York, money was tight, and as she had in Cleveland, she supplemented her income with public lectures. More important, she met the women who would help shape her career and her political agenda. These included the Reverend Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), 1904-1915; Carrie Chapman Catt, the brilliant NAWSA president usually credited with devising the “winning strategy” for achieving the vote; and Maude Wood Park, the organizer of the College Equal Suffrage Organization. Park gave Allen a job as the organization’s secretary. Although initially viewed as wild revolutionaries by many Americans, these suffragists led the movement into the moderate mainstream, especially after the break with the more radical National Women’s Party. This way led to victory in 1920.

Pragmatic by necessity, the NAWSA endorsed no political candidate unless he endorsed woman suffrage. Suffragists argued for the vote on the grounds that women were equal to men and deserved equal treatment and also, often simultaneously, that women were different and would bring their special nurturing skills to politics and the larger community, especially the lives of women. These became Allen’s guiding principles.

SECOND ACTS: POLITICAL THEATER

In 1912, one of many proposed amendments to the Ohio constitution would have enfranchised Ohio women by changing the words that described a voter as a “white male” to “every citizen.” Allen returned to Cleveland to make it happen. She was already well-known to Clevelanders, thanks to her family connections and her byline at the newspaper.

She was also a polished public speaker. Like her fellow suffragists, she was well educated and well off financially, but unlike them, she was neither shy nor modest. Accompanied by cub reporter Louis Seltzer, she and other brave women rode from Cleveland to Medina on a rented trolley that carried a “Votes for Women” banner; when it stopped, Allen hopped off and pitched woman suffrage from a soap box. [14] Suffragists were routinely greeted by hecklers, who told them to return to their homes where they belonged. “It can’t be did,” maintained one opponent to votes for women, “and if it can be did, it hain’t right.” [15] More frustrating was public indifference. Allen recalled a meeting in one small town at which only two women appeared; she urged them to return the next night, and they did, bringing one friend. On the brighter side, she was “roundly cheered” in a circus tent in Ottawa, Ohio, and in Sidney, Ohio, at a band concert, accompanied by another suffragist, who entertained the crowd by whistling and playing the cornet. She spoke and organized women all over the state – 92 speeches in 88 counties [16] The referendum lost by 87,455 votes, but Allen’s exposure laid the groundwork for her successful runs for state-wide office in 1922 and 1928.

Ohio women organized a second effort to amend the Ohio constitution in 1914, using the initiative. Allen again took to the lecture circuit; she shared a platform with fellow supporter, Cleveland Mayor Newton D. Baker in March, 1914. [17] As Baker watched from the grandstand, a great parade of 10,000 women and men, including Allen, marched through Cleveland streets on October 4. [18] Allen predicted a win: “I have visited more than forty Ohio counties in this campaign … [M]any women opposed to suffrage two years ago now are heartily in favor of it…. [M]en are changing from a position of direct opposition or indifference to open espousal.” [19] Her colleagues chose her to debate the prominent anti-suffragist Lucy Price in Gray’s Armory. Anti-suffragists, often wealthy and well-educated women like the suffragists themselves, argued that women’s place was in the home, not the polling place, and moreover, most women didn’t want to vote. Allen took the opposite position. Both arguments would have been difficult to prove. Although no official winner was announced, Allen felt that she had won and accused her opponent of calling her “a short and ugly name.” [20] The initiative failed by an even greater margin than had the 1912 amendment.

Temporarily thwarted at the state level, suffragists switched tactics. Persuaded by Allen and other suffragists, the authors of East Cleveland’s new charter in 1916 included a provision that allowed women to vote in municipal elections. The provision was challenged by the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections. The Cleveland Woman Suffrage League filed a taxpayers’ suit against the board. Allen was their attorney and won the case before the Ohio Supreme Court.

This victory, plus her name recognition, won her the attention of the local Democratic Party, which appointed her an assistant county prosecutor. This became the beginning of her judicial career.

Even before the suffrage amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920, Allen launched her campaign for municipal judge. Because it was too late to enter a party primary, she quickly organized a petition campaign to get her name on the ballot. Her fellow suffragists, many now members of the new League of Women Voters, came to her aid, as she had to theirs. Allen herself spoke often, now on her own behalf. Once in the race, she was endorsed by the league, by the Business and Professional Women and a host of other women’s organizations, and by all four Cleveland newspapers. She led the field of ten judicial candidates.[21]

Allen ran as a non-partisan. She believed that judges should not be closely identified with one party or the other. Moreover, she had broken with Democratic leader Baker over his endorsement of universal military training when he was Secretary of War during World War I. She also hoped to get votes from both Democrats and Republicans, which she did. [22]

During these years in Cleveland, Allen met the leaders of the local suffrage movement like Harriet Taylor Upton, Elizabeth Hauser, Belle Sherwin, Zara DuPont, Lucia McBride, Mary B. Grossman, and dozens of others. “Society women, professional women, rich women, poor women – a noble band of good workers.”[23] She made personal friends and political alliances that would stand her in good stead for the rest of her career. She never forgot them; they never forgot her. “I was the beneficiary of the entire woman movement,” she acknowledged. [24]

ON THE MAIN STAGE: FIRST LADY OF THE LAW

Within months of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and with these women’s help, Allen took her seat as Cleveland’s first female judge of the Common Pleas court. She prided herself on her efficiency in the dispatch of justice. On the grounds that she was single, she refused to be sidelined to divorce court, choosing criminal law. “[25] This was where the action was: Cleveland was then under siege by “organized and unorganized criminals” who robbed and murdered citizens, including policemen, almost with impunity. [26] In her first term, 1921-1922, she disposed of 892 cases.[27]

Two of those cases made headlines. The first involved a 1921 payroll robbery in which two men were murdered by a gang implicated in several other robberies. Their leader, Frank Motto, fled to California but was returned to Cleveland and Allen’s court. In May 1921, during the jury trial, she had to clear the courtroom of suspicious looking men, who were carrying weapons. She herself received a death threat: “On the day Motto dies, you die.” [28] The Cleveland Plain Dealershouted: “JUDGE ALLEN SENTENCES SLAYER …. In a calm, even tone, Judge Florence E. Allen pronounced the death penalty.” [29] Motto died in the electric chair in August. Allen got police protection, became the “first woman judge to impose the death sentence,” and created a reputation as a fearless enforcer of law and order. [30]

She enhanced that reputation by sentencing a fellow jurist, former chief justice of the Common Pleas Court, William Henry McGannon, to jail for perjury. He had twice been acquitted of murder. The Cleveland Bar Association, however, prosecuted him, and others, for false statements made during the trials. Despite Allen’s efforts, bribes and witness-tampering took place before McGannon’s trial. The jury found McGannon guilty, and Allen sentenced him to one to ten years in the penitentiary. “[A] court has never been faced with a more disagreeable duty than that of sentencing a man before whom the court has practiced as a lawyer,” she reproached him. [31]

It was a spectacular first act, but Allen had set her sights higher. In the summer of 1922, she briefly contemplated running for the U.S. Senate against the incumbent, Atlee Pomerene. Instead, encouraged by Baker, she ran for a vacant seat on the Ohio Supreme Court. [32] The Cleveland Plain Dealer applauded: “her election was one of the best things that ever happened to this [Common Pleas] court …. [H]er service on the lower bench fully entitles her to aspire to the higher office.” [33]Her usual allies, former suffragists and women’s organizations, again organized her campaign. She again ran a non-partisan campaign and won handily, the first woman to be elected to a state supreme court. Six years later, as her term drew to a close, she again contemplated the Senate. Without the endorsement of the Democratic party but encouraged by women’s groups offended by Pomerene’s lamentable record on woman suffrage, she ran in the primary against him. She lost but by a small margin. [34]

Allen won re-election to the Ohio Supreme Court in 1928, but in 1932, hoping to add to a Democratic landslide, she made a run for the U.S. House. She lost to Republican Chester C. Bolton, but she received her reward in March 1934, when she was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, the first woman to sit on the federal bench. Clevelanders honored her with a banquet, “an expression of esteem from the Cleveland Bar Association and the women of the city for Judge Allen’s achievements in her profession.” Organizers included women who had fought for suffrage with Allen two decades earlier. [35] She was appointed the court’s chief justice in 1958, the first woman to hold this appointment.

Allen also became the first to be seriously considered for a Supreme Court position by Roosevelt and subsequent presidents. Although she had strong support from local and national women’s organizations and political connections in Washington, she never received the appointment. She claimed that she did not “expect such an appointment,” [36] but many of her supporters wanted it for her, and certainly so did she.

Perhaps her academic and professional credentials, both limited by her gender, were not strong enough. Perhaps she was too closely identified as a Democrat; perhaps not closely enough. Perhaps Americans just weren’t ready for a woman on the highest court of the land. [37] Not until 1981 did Sandra Day O’Connor get appointed to the Supreme Court.

Allen was a pioneer judge but not a pioneer jurist. The decisions she was proudest of supported the familiar agenda of the suffragists and the women’s organizations who had always backed her (the death penalty being the exception). In Reutner v. City of Cleveland(1923) she ruled that Cleveland had the right to adopt a city manager plan and proportional representation. The League of Women Voters advocated both and continued to support the city manager plan long after Cleveland voters rejected it in 1931. The league also favored laws that protected women in the workplace. Although the decision was not gender-specific, in Ohio Automatic Sprinkler Co. v. Fender(1923) Allen voted with the majority of her colleagues to over-rule lower courts and hold the company responsible for the woman employee’s injury. Women’s organizations continued to support special legislation for women in the workplace until the 1970s.

Her most significant decision – in January 1938 on the appeals court – ruled in favor of the New Deal’s Tennessee Valley Authority. The issue was whether the federal government had the authority to build the dams and waterways that would control flooding in the region and also market electric power. Private power companies argued that this was unfair competition. The League of Women Voters had endorsed an earlier version of the plan in the late 1920s. [38] Clevelanders were familiar with publicly owned utilities because of the municipal power plant established in 1914 when Baker was mayor of Cleveland. In 1937, however, Baker was, initially, the lead attorney for the private power companies. His side lost. Allen’s decision held that the TVA did not unfairly compete with private enterprise and more importantly, it upheld the federal government’s broad use of its powers. Allen herself, in full judicial regalia, read aloud for an hour her decision before an excited, expectant audience in a jam-packed courtroom. [39] She was upheld by the Supreme Court.

This was probably her last bravura performance although she served on the appeals court until 1959. After retirement, Allen continued to make news, traveling and lecturing. In 1965, she published her memoir, To Do Justly.

During her long career on the bench, she had no opportunity to rule on women’s rights cases; those would emerge with second-wave feminism after her retirement. In any case, despite her own unconventional life, she had conventional ideas about women’s responsibilities: family, home, work if necessary, and service to the community. Perhaps reflecting on the political challenges she herself had faced, she predicted, “No woman, no matter how qualified, will be nominated, much less elected, President of the United States.” [40] Allen was more like Sandra Day O’Connor – better known for her ability to get along with male judges [41]– than like the trail-blazing feminist, Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

When Allen died in September 1966, the Cleveland Plain Dealerlamented the passing of this “distinguished, well-loved citizen.” [42]

ENCORE, ENCORE

Distinguished and well-loved, but soon forgotten. Why?

Maybe because she was from Cleveland, and most famous people are from somewhere else.

Maybe even Clevelanders don’t think Cleveland history is interesting enough to remember. Dr. Jeannette Tuve’s is the only definitive biography of Allen. The Cleveland Public Library system owns three copies; only one circulates. Allen’s contemporary, sometime friend and sometime foe but always more famous, Newton D. Baker, doesn’t do much better. The Cleveland Public Library system owns four copies of Clarence C.H. Cramer, Newton D. Baker: A Biography (Cleveland: World Publishing, 1961) and three copies of Douglas B. Craig, Progressives at War: William G. McAdoo and Newton D. Baker, 1863-1941(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

Maybe it’s just easier to forget women, even women like Allen who lived very public lives.

Of course, periodically we do “remember the ladies,” as Abigail Adams advised her husband John as he contemplated the American Revolution and she contemplated what freedom from the British might mean for those who were not male. John and his colleagues didn’t heed his wife’s advice.

In the 1910s and 1920s, when it looked as though the suffrage movement might, like the American Revolution, turn the world upside down, politicians remembered women – Allen, for example. But in the following decades, attention turned to other things – the Great Depression and World War II, for example.

And then in the 1970s in the heady days of second-wave feminism, born of the civil rights movement, we re-discovered women in the American past. Like Simakis, we were astonished – and exhilarated. We knew about the men, of course, – the presidents, the generals, the industrialists. No one had ever mentioned that there were women back then. You’d think we could have figured it out. And we did, and then forgot.

And today, in 2019, in the context of Hillary Clinton almost becoming President in 2016 and a record number of women elected to Congress in 2018 and because it is almost a hundred years since Allen and others fought for the vote – and Americans like centennials -, we are re-discovering women one more time.

But this story of Cleveland’s most famous woman reminds us that fame is fleeting. Simakis suggested – as Plain Dealer reporter Tom Suddes had earlier[43]– a remedy for our faulty public memory: a courthouse named for Allen, a more substantial memorial than existing portraits and plaques. Simakis’s readers were enthusiastic. Howard M. Metzenbaum and Carl B. Stokes have their names on courthouses: why not “the gutsy, unstoppable FEA”? One reader suggested that Allen’s life would make a good play. Simakis concluded, “I can see the actress in Allen’s robes now, sitting in her chambers, opening that smudgy death threat [during the Motta trial] … [F]or sheer drama, her tenure as a judge in Cleveland is hard to beat.” [44]

Allen was that actress; her whole life was that drama – from her five-year-old recitation of the Greek alphabet to her hour-long reading of her decision in the TVA case and all the lectures and stump speeches and marches and headlines in between. These made her Cleveland’s most famous woman. For a while.

[1] Plain Dealer, June 30, 2019: B3.

[2] Don’t take my word for it. Reporter Grace Goulder described Allen as “Ohio’s most famous woman”, “Ohio’s first lady,” and the “world’s best known woman lawyer”: Cleveland Plain Dealer (CPD), October 6, 1935: 67. By my count, from 1900 to 2019, she got 1,466 mentions in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and for almost all those years, there was more than one Cleveland newspaper.

[3] Allen had the good sense and sturdy ego to leave her papers to the Western Reserve Historical Society. These became the basis for her definitive biography: Jeannette E. Tuve, First Lady of the Law: Florence Ellinwood Allen(Boston and London, University Press of America , 1984).

[4] Florence Ellinwood Allen, To Do Justly(Cleveland: The Press of Western Reserve University, 1965), 1.

[5] Allen, 9-10.

[6] Tuve, 10.

[7] Allen, 19.

[8] Tuve, 11.

[9]Allen, 19

[10] Allen, 20.

[11] Tuve, 12.

[12] Allen, 26;28; 31. Virginia Clark Abbott, The History of Woman Suffrage and the League of Women Voters in Cuyahoga County, 1911-1945(Cleveland: n.p. c. 1949), 52.

[13] Tuve, 18.

[14] Cleveland Plain Dealer (CPD),June 25, 1912: 12.

[15] Abbott, 54.

[16] Allen, 32.

[17] CPD, March 3, 1914: 14.

[18] Abbott, 38.

[19] CPD, October 10, 1914: 5.

[20] Allen, 34. What name can this have been?

[21] Allen, 43-44.

[22] Tuve, 54.

[23]Florence E. Allen and Mary Welles, The Ohio Woman Suffrage Movement(Committee for the Preservation of Ohio Woman Suffrage Records, 1952), 41.

[24] Allen, 43.

[25] Allen, 46.

[26] John Stark Bellamy, The Maniac in the Bushes and More Tales of Cleveland Woe(Cleveland: Gray and Company Publishers, 1997), 219.

[27] Allen, 51.

[28] Allen, 28.

[29] CPD, May 15, 1921: 1.

[30] Allen, 56.

[31] Allen, 62. McGannon was released after 19 months because he had diabetes.

[32] Tuve, 63.

[33] CPD, June 14, 1922: 6.

[34] Allen, 75-77.

[35] CPD, March 25, 1934:16.

[36] Allen, 110.

[37] Tuve, 124-126.

[38] Tuve, 117.

[39] Tuve, 116-122.

[40] Quoted in Tuve, 141.

[41] Evan Thomas. First: Sandra Day O’Connor(New York: Random House, 2019).

[42] CPD, September 17, 1966: 14.

[43] Plain Dealer, June 7, 2000: B9; January 9, 2002: 9B.

[44] Plain Dealer, July 21, 2019: B 1, B 3. I can’t resist pointing out that the Newton D. Baker Building on the Case Western Reserve University campus has been demolished. Brick and mortar are no guarantee that you’ll be remembered.

In a State of Access: Ohio Higher Education, 1945 – 1990

In a State of Access: Ohio Higher Education, 1945 – 1990

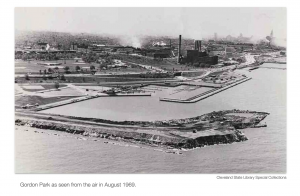

Rockefeller Park: The crown jewel of University Circle; the vision of 19th Century benefactors

Rockefeller Park: The crown jewel of University Circle; the vision of 19th Century benefactors