Dr. John Grabowski, Congressman Dennis Kucinich, James JT Toman and Greg Deegan discuss Mayor Tom L. Johnson (1901-1909) when Cleveland, OH was known as “The City on the Hill”

Created by: Nicole Majercak, Donald Majercak, Richard Kiovsky for Teaching Cleveland

Category: Progressive Era: 1900-1920

Georgism from Wikipedia

Georgism (also called Geoism) is an economic philosophy and ideology that holds that people own what they create, but that things found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all.[1] The Georgist philosophy is based on the writings of the economist, Henry George(1839-1897), and is usually associated with the idea of a single tax on the value of land. Georgists argue that a tax on land value iseconomically efficient, fair and equitable; and that it can generate sufficient revenue so that other taxes, which are less fair and efficient (such as taxes on production, sales and income), can be reduced or eliminated. A tax on land value has been described by many as aprogressive tax, since it would be paid primarily by the wealthy, and would reduce income inequality.[2]

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Main tenets

According to Henry George, political economy proceeds from the simple axiom: “People seek to satisfy their desires with the least exertion.”[3]George believed that although scientific experiments could not be carried out in political economy, theories could be tested by comparing different societies with different conditions and through thought experiments about the effects of various factors.[3] Applying this method, George concluded that many of the problems that beset society, such as poverty, inequality, and economic booms and busts, could be attributed to the private ownership of the necessary resource, land.

Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared equally by the people of a society rather than being owned privately. George held that people own what they create, but that things found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all.[1] In his publication Progress and Poverty George argued that: “We must make land common property.”[4] Although this could be done by nationalizing land and then leasing it to private parties, George preferred taxing unimproved land value, in part because this would be less disruptive and controversial in a country where land titles have already been granted to individuals.

It was Adam Smith who first noted the properties of a land value tax in his book, The Wealth of Nations:[5]

Ground-rents are a still more proper subject of taxation than the rent of houses. A tax upon ground-rents would not raise the rents of houses. It would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent, who acts always as a monopolist, and exacts the greatest rent which can be got for the use of his ground. More or less can be got for it according as the competitors happen to be richer or poorer, or can afford to gratify their fancy for a particular spot of ground at a greater or smaller expense.In every country the greatest number of rich competitors is in the capital, and it is there accordingly that the highest ground-rents are always to be found. As the wealth of those competitors would in no respect be increased by a tax upon ground-rents, they would not probably be disposed to pay more for the use of the ground. Whether the tax was to be advanced by the inhabitant, or by the owner of the ground, would be of little importance. The more the inhabitant was obliged to pay for the tax, the less he would incline to pay for the ground; so that the final payment of the tax would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent.

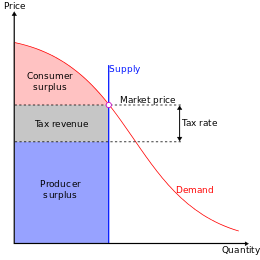

Standard economic theory suggests that a land value tax would be extremely efficient – unlike other taxes, it does not reduce economic productivity.[2] Nobel laureate Milton Friedman agreed that Henry George’s land value tax is potentially beneficial for society since, unlike other taxes, it would not impose an excess burden on economic activity (leading to “deadweight loss“). A replacement of other more distortionary taxes with a land value tax would thus improve economic welfare.[6]

Georgists suggest two uses for the revenue from a land value tax. The revenue can be used to fund the state, or it can be redistributed to citizens as a pension or basic income (or it can be divided between these two options). If the first option were to be chosen, the state could avoid having to tax any other type of income or economic activity. In practice, the elimination of all other taxes implies a very high land value tax, higher than any currently existing land tax. Introducing a high land value tax would cause the price of land titles to decrease correspondingly, but George did not believe landowners should be compensated, and described the issue as being analogous to compensation for former slave owners. Additionally, a land value tax would be a tax of wealth, and so would be a form of progressive taxation and tend to reduce income inequality. As such, a defining argument for Georgism is that it taxes wealth in a progressive manner, reducing inequality, and yet it also reduces the strain on businesses and productivity.

Georgists also argue that all economic rent (i.e., unearned income) collected from natural resources (land, mineral extraction, the broadcast spectrum, tradable emission permits,fishing quotas, airway corridor use, space orbits, etc.) and extraordinary returns from natural monopolies should accrue to the community rather than a private owner, and that no other taxes or burdensome economic regulations should be levied. Modern environmentalists find the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity appealing, and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform as a replacement for command and control regulation. This would entail substantial taxes or fees for pollution, waste disposal and resource exploitation, or equivalently a “cap and trade” system where permits are auctioned to the highest bidder, and also include taxes for the use of land and other natural resources.[citation needed]

[edit]Synonyms and variants

Most early advocacy groups described themselves as Single Taxers, and George endorsed this as being an accurate description of the philosophy’s main political goal – the replacement of all taxes with a land value tax. During the modern era, some groups inspired by Henry George emphasize environmentalism more than other aspects, while others emphasize his ideas concerning economics.

Some devotees are not entirely satisfied with the name Georgist. While Henry George was well-known throughout his life, he has been largely forgotten by the public and the idea of a single tax of land predates him. Some people now use the term “Geoism”, with the meaning of “Geo” deliberately ambiguous. “Earth Sharing”[7] “Geoism“,[8] “Geonomics” [9] and “Geolibertarianism“[10] (see libertarianism) are also preferred by some Georgists; “Geoanarchism” is another one.[11] These terms represent a difference of emphasis, and sometimes real differences about how land rent should be spent (citizen’s dividend or just replacing other taxes); but all agree that land rent should be recovered from its private recipients.

[edit]Influence

Georgist ideas heavily influenced the politics of the early 1900s, during its heyday. Political parties that were formed based on Georgist ideas include the Commonwealth Land Party, the Justice Party of Denmark, and the Single Tax League.

In the UK during 1909, the Liberal Government included a land tax as part of several taxes in the People’s Budget aimed at redistributing wealth (including a progressively graded income tax and an increase of inheritance tax). This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. The budget was passed eventually – but without the land tax. In 1931 the minority Labour Government passed a land value tax as part III of the 1931 Finance act. However this was repealed in 1934 by the National Governmentbefore it could be implemented. In Denmark, the Georgist Justice Party has previously been represented in Folketinget. It formed part of a centre-left government 1957-60 and was also represented in the European Parliament 1978-79. The influence of Henry George has waned over time, but Georgist ideas still occasionally emerge in politics. In the 2004 Presidential campaign, Ralph Nader mentioned Henry George in his policy statements.[12]

[edit]Communities

Several communities were also initiated with Georgist principles during the height of the philosophy’s popularity. Two such communities that still exist are Arden, Delaware, which was founded during 1900 by Frank Stephens and Will Price, and Fairhope, Alabama, which was founded during 1894 by the auspices of the Fairhope Single Tax Corporation.

The German protectorate of Jiaozhou Bay (also known as Kiaochow) in China fully implemented Georgist policy. Its sole source of government revenue was the land value tax of six percent which it levied on its territory. The German government had previously had economic problems with its African colonies caused by land speculation. One of the main aims in using the land value tax in Jiaozhou Bay was to eliminate such speculation, an aim which was entirely achieved.[13] The colony existed as a German protectorate from 1898 until 1914 when it was seized by Japan. In 1922 it was returned to China.

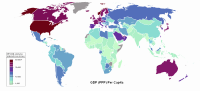

Georgist ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions.[14] Many municipal governments of the USA depend on real property tax as their main source of revenue, although such taxes are not “Georgist” as they generally include the value of buildings and other improvements, one exception being the town of Altoona, Pennsylvania, which only taxes land value.

[edit]Institutes and organizations

Various organizations still exist that continue to promote the ideas of Henry George. According to the The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, the periodicalLand&Liberty, established in 1894, is the “the longest-lived Georgist project in history”.[15] Also in the U.S., the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy was established in 1974 founded based on the writings of Henry George, and “seeks to improve the dialogue about urban development, the built environment, and tax policy in the United States and abroad”.[16] TheHenry George Foundation continues to promote the ideas of Henry George in the UK.[17] The IU, is an international umbrella organisation that brings together organizations worldwide that seek land value tax reform.[18]

[edit]Criticism

Although both advocated workers’ rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition to communism. He argued that, “The whole thing is… simply an attempt, decked out with socialism, to save capitalist domination and indeed to establish it afresh on an even wider basis than its present one.”[19] Marx also criticized the way land value tax theory emphasizes the value of land, arguing that, “His fundamental dogma is that everything would be all right if ground rent were paid to the state.”[19]

On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx’s ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[20][21][page needed] Fred Harrison provides a full treatment of Marxist objections to land value taxation and Henry George in “Gronlund and other Marxists – Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics”, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, (Nov 2003).[22]

George has also been accused of exaggerating the importance of his “all-devouring rent thesis” in claiming that it is the primary cause of poverty and injustice in society.[23] More recent critics have claimed that increasing government spending has rendered a land tax insufficient to fund government.[citation needed] Georgists have responded by citing a multitude of sources showing that the total land value of nations like the US is enormous, and more than sufficient to fund government.[24]

[edit]Notable people influenced by Georgism

- Matthew Bellamy – member of the alternative rock band,Muse [25]

- Ralph Borsodi [26]

- William F. Buckley, Jr. [27]

- Vince Cable – UK Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Liberal DemocratsDeputy Leader and Shadow Chancellor.

- Winston Churchill [28]

- Nick Clegg – Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, leader of the Liberal Democrats

- Clarence Darrow[29]

- Michael Davitt [30]

- Albert Einstein[31]

- Fred Foldvary, PhD – Lecturer in Economics, Santa Clara University[32]

- Henry Ford[33]

- M. Mason Gaffney, PhD – Economics professor at theUniversity of California at Riverside [34]

- David Lloyd George [28]

- George Grey [35]

- Walter Burley Griffin[36]

- Bolton Hall, New York City activist[37]

- Fred Harrison – Research Director of the London-based Land Research Trust[38]

- William Morris Hughes – seventh Prime Minister of Australia (1915–1923)[39]

- Bill Moyers[40]

- Aldous Huxley[41]

- Blas Infante [42]

- Mumia Abu-Jamal[43]

- Tom L. Johnson[44]

- Samuel M. Jones – Mayor ofToledo, Ohio (1897 to 1904)[45]

- Wolf Ladejinsky [46]

- Suzanne La Follette – American journalist &libertarian feminist [47]

- Elizabeth Magie,.[48]

- Ralph Nader[12]

- Francis Neilson – Actor, playwright, stage director, Member of the British House of Commons, avid lecturer, and author[49]

- Albert Jay Nock[50]

- Herbert Simon – Winner of theNobel Memorial Prize in Economics (1978)[51]

- Raymond A. Spruance[52]

- Joseph Stiglitz – Winner of theNobel Memorial Prize in Economics (2001)[53]

- Leo Tolstoy[54]

- William Simon U’Ren[55]

- William Vickrey – Winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (1996)[56]

- Frank Lloyd Wright[57]

- Sun Yat-sen [58]

[edit]See also

- Excess burden of taxation

- Mutualism

- Economic democracy

- Geolibertarianism

- Bolton Hall (activist), a proponent of the theory

- Progress and Poverty

- Protection or Free Trade

- Tragedy of the anticommons

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b Heavey, Jerome F. (07 2003). “Comments on Warren Samuels’ “Why the Georgist movement has not succeeded””. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 62(3): 593-599. Retrieved 29 July 2011. “human beings have an inalienable right to the product of their own labor”.

- ^ a b Land Value Taxation: An Applied Analysis, William J. McCluskey, Riël C. D. Franzsen

- ^ a b Progress and Poverty – “Introduction: The Problem of Poverty Amid Progress

- ^ George, Henry (1879). “2”. Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. VI. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ The Wealth of Nations Book V, Chapter 2, Article I: Taxes upon the Rent of Houses.

- ^ Foldvary, Fred E. “Geo-Rent: A Plea to Public Economists”. Econ Journal Watch (April 2005)[1]

- ^ Introduction to Earth Sharing,

- ^ Socialism, Capitalism, and Geoism – by Lindy Davies

- ^ Geonomics in a Nutshell

- ^ Geoism and Libertarianism by Fred Foldvary

- ^ Geoanarchism: A short summary of geoism and its relation to libertarianism – by Fred Foldvary

- ^ a bhttp://web.archive.org/web/20040828085138/http://www.votenader.org/issues/index.php?cid=7

- ^ Silagi, Michael and Faulkner, Susan N., , Land Reform in Kiaochow, China: From 1898 to 1914 the Menace of Disastrous Land Speculation was Averted by Taxation, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, volume 43, Issue 2, pages 167-177

- ^ Gaffney, M. Mason. “Henry George 100 Years Later”. Association for Georgist Studies Board. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 62, 2003, p. 615

- ^ http://www.lincolninst.edu/aboutlincoln/

- ^ “The Henry George Foundation”. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ The IU. “The IU”. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ a b Karl Marx – Letter to Friedrich Adolph Sorge in Hoboken

- ^ http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/mceachran_hgeorge_and_kmarx.html

- ^ Henry George’s Thought [1878822810] – $49.95 : Zen Cart!, The Art of E-commerce

- ^ 14 Gronlund and other Marxists – Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics | American Journal of Economics and Sociology, The | Find Articles at BNET

- ^ Critics of Henry George

- ^ Looking For Rents In All the Right Places

- ^ Muse return with new album The Resistance “Sure, he has already launched into a passionate soliloquy about Geoism (the land-tax movement inspired by the 19th-century political economist Henry George)“.

- ^ Carlson, Allan. The New Agrarian Mind: The Movement Toward Decentralist Thought in Twentieth-Century America Transaction Publishers, 2004 (pg 51).

- ^ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Buckley_HG.html William F. Buckley, Jr. Transcript of an interview with Brian Lamb, CSpan Book Notes, April 2–3, 2000

- ^ a b People’s Budget

- ^ Transcript of a speech by Darrow on taxation

- ^ Lane, Fintan. The Origins of Modern Irish Socialism, 1881-1896.Cork University Press, 1997 (pgs.79,81).

- ^ Two lettrs written in 1934 to Henry George’s daughter, Anna George De Mille. In one letter Einstein writes, “Men like Henry George are rare unfortunately. One cannot imagine a more beautiful combination of intellectual keenness, artistic form and fervent love of justice.“

- ^ Fred Foldvary’s website

- ^ Transcript of 1942 interview with Henry Ford in which he says, “The time will come when not an inch of the soil, not a single crop, not even weeds, will be wasted. Then every American family can have a piece of land. We ought to tax all idle land the way Henry George said — tax it heavily, so that its owners would have to make it productive“.

- ^ Mason Gaffney’s homepage

- ^ The Life of Henry George, Part 3 Chapter X1

- ^ Co-founder of the Henry George Club, Australia.

- ^ Leubuscher, F. C. (1939). Bolton Hall. The Freeman. January issue.

- ^ Fred Harrison’s website

- ^ “Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862 – 1952)”. Australian Dictionary of Biography: Online Edition.

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Za-TYGOE1O0&t=38m0s

- ^ Harrison, F. (1989). Aldous Huxley on ‘the Land Question’. Land & Liberty. May – June issue.

- ^ Arcas Cubero, Fernando: El movimiento georgista y los orígenes del Andalucismo : análisis del periódico “El impuesto único” (1911-1923). Málaga : Editorial Confederación Española de Cajas de Ahorros, 1980. ISBN 8450037840

- ^ Justice for Mumia Abu-Jamal

- ^ “Single Taxers Dine Johnson”. New York Times May 31, 1910.

- ^ “Henry George”. Ohio History Central: An Online History of Ohio History.

- ^ Andelson Robert V. (2000). Land-Value Taxation Around the World: Studies in Economic Reform and Social Justice Malden. MA:Blackwell Publishers, Inc. Page 359.

- ^ Suzanne La Follette: The Freewoman

- ^ Magie invented The Landlord’s Game, predecessor to Monopoly

- ^ “Henry George, The Scholar” – A Commencement Address Delivered by Francis Neilson at the Henry George School of Social Science, June 3, 1940.

- ^ Henry George: Unorthodox American by Albert Jay Nock

- ^ Quotes from Nobel Prize Winners Herbert Simon stated in 1978: “Assuming that a tax increase is necessary, it is clearly preferable to impose the additional cost on land by increasing the land tax, rather than to increase the wage tax — the two alternatives open to the City (of Pittsburgh). It is the use and occupancy of property that creates the need for the municipal services that appear as the largest item in the budget — fire and police protection, waste removal, and public works. The average increase in tax bills of city residents will be about twice as great with wage tax increase than with a land tax increase.“

- ^ Thomas B. Buell (1974). The Quiet Warrior. Boston: Little, Brown.

- ^ December 2010 video, in which Stiglitz calls Henry George a “great progressive” and advocates for the land tax

- ^ .Article on Tolstoy, Proudhon and George. Count Tolstoy once said of George, “People do not argue with the teaching of George, they simply do not know it“.

- ^ “Oregon Biographies: William S. U’Ren”. Oregon History Project. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. 2002. Archived from the original on 2006-11-10. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ Bill Vickrey – In Memoriam

- ^ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Wright_HG%27s_Remedy.html

- ^ Trescott, P. B. (1994). Henry George, Sun Yat-sen and China: more than land policy was involved. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53, 363-375.

Henry George from Wikipedia

| Classical economics | |

|---|---|

Henry George |

|

| Born | September 2, 1839 |

| Died | October 29, 1897 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | American |

| Contributions | Georgism; studied land as a factor in economic inequalityand business cycles; proposed land value tax |

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American writer, politician and political economist, who was the most influential proponent of the land value tax, also known as the “single tax” on land. He inspired the economic philosophy known asGeorgism, whose main tenet is that people should own what they create, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all humanity. His most famous work, Progress and Poverty (1879), is a treatise on inequality, the cyclic nature of industrial economies, and the use of the land value tax as a possible remedy.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Early life and marriage

George was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a lower-middle class family, the second of ten children of Richard S. H. George and Catharine Pratt (Vallance) George. His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He returned to Philadelphia after 14 months at sea to become an apprentice typesetter before settling in California. After a failed attempt at gold mining he began work with the newspaper industry during 1865, starting as a printer, continuing as a journalist, and ending as an editor and proprietor. He worked for several papers, including four years (1871–1875) as editor of his own newspaper San Francisco Daily Evening Post.

In California, George became enamored of Annie Corsina Fox, an eighteen-year-old Australian girl who had been orphaned and was living with an uncle. The uncle, a prosperous, strong-minded man, was opposed to his niece’s impoverished suitor. But the couple, defying him, eloped and married during late 1861, with Henry dressed in a borrowed suit and Annie bringing only a packet of books. The marriage was a happy one and four children were born to them. Fox’s mother was Irish Catholic, and while George remained an Evangelical Protestant, the children were raised Catholic. On November 3, 1862 Annie gave birth to future United States Representative from New York, Henry George, Jr. (1862–1916). Early on, even with the birth of future sculptor, Richard F. George(1865–September 28, 1912),[1][2][3] the family was near starvation, but George’s increasing reputation and involvement in the newspaper industry lifted them from poverty.

George’s other two children were both daughters. The first was Jennie George, (c. 1867 – 1897), later to become Jennie George Atkinson.[4] George’s other daughter was Anna Angela George, (b. 1879), who would become mother of both future dancer and choreographer, Agnes de Mille [5] and future actress Peggy George, (who was born Margaret George de Mille).[6][7]

[edit]Economic and political philosophy

George began as a Lincoln Republican, but then became a Democrat, once losing an election to the California State Assembly. He was a strong critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors.

One day during 1871 George went for a horseback ride and stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He later wrote of the revelation that he had:

| “ | I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, ‘I don’t know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.’ Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.[8] | ” |

Furthermore, on a visit to New York City, he was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that long-established city were much worse off than the poor in less developed California. These observations supplied the theme and title for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty, which was a great success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by social and technological advances in a free market economy is possessed by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the main cause of poverty. George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and indicated that such a system was equivalent to slavery—a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery.

George was in a position to discover this pattern, having experienced poverty himself, knowing many different societies from his travels, and living in California at a time of rapid growth. In particular he had noticed that the construction of railroads in California was increasing land values and rents as fast or faster than wages were rising.

During 1880, now a popular writer and speaker,[9] George moved to New York City, becoming closely allied with the Irish nationalist community despite being of English ancestry. From there he made several speaking journeys abroad to places such asIreland and Scotland where access to land was (and still is) a major political issue. During 1886 George campaigned for mayor of New York City as the candidate of the United Labor Party, the short-lived political society of the Central Labor Union. He polled second, more than the Republican candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The election was won by Tammany Hall candidate Abram Stevens Hewitt by what many of George’s supporters believed was fraud. In the 1887 New York state elections George came in a distant third in the election for Secretary of State of New York. The United Labor Party was soon weakened by internal divisions: the management was essentially Georgist, but as a party of organised labor it also included some Marxist members who did not want to distinguish between land and capital, many Catholic members who were discouraged by the excommunication of FatherEdward McGlynn, and many who disagreed with George’s free trade policy. Against the advice of his doctors, George campaigned for mayor again during 1897, this time as an Independent Democrat.

[edit]Death

Henry George died of a stroke four days before the election.[10] An estimated 100,000 people attended his funeral on Sunday, October 30, 1897 where the Reverend Lyman Abbott delivered an address,[11] “Henry George: A Remembrance”.[12]

[edit]Policy proposals

[edit]Single tax on land

Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared by society rather than being owned privately. The clearest statement of this view is found in Progress and Poverty: “We must make land common property.”[13] By taxing land values, society could recapture the value of its common inheritance, and eliminate the need for taxes on productive activity.

Modern-day environmentalists[who?] have agreed with the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity – and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform, including substantial taxes or fees on pollution as a replacement for “command and control” regulation.

[edit]Free trade

George was opposed to tariffs, which were at the time both the major method of protectionist trade policy and an important source of federal revenue (the federal income tax having not yet been introduced). Later in his life, free trade became a major issue in federal politics and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen.

[edit]Chinese immigration

Some of George’s earliest articles to gain him fame were on his opinion that Chinese immigration should be restricted.[14] Although he thought that there might be some situations in which immigration restriction would no longer be necessary and admitted his first analysis of the issue of immigration was “crude”, he defended many of these statements for the rest of his life.[15] In particular he argued that immigrants accepting lower wages had the undesirable effect of forcing down wages generally. He acknowledged, however, that wages could only be driven down as low as whatever alternative for self-employment was available.

[edit]Secret ballots

George was one of the earliest, strongest and most prominent advocates for adoption of the Secret Ballot in the U.S.A. [16]

[edit]Hard currency and national debt

George supported government issued notes such as the greenback rather than gold or silver currency or money backed by bank credit.[17]

[edit]Subsequent influence

In the United Kingdom during 1909, the Liberal Government of the day attempted to implement his ideas as part of the People’s Budget. This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. George’s ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions.

Fairhope, Alabama was founded as a colony by a group of his followers as an experiment to try to test his concepts.

Although both advocated worker’s rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition tocommunism.[18] On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx’s ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[19]

Henry George’s popularity decreased gradually during the 20th century, and he is little known today. However, there are still many Georgist organizations in existence. Many people who still remain famous were influenced by him. For example, George Bernard Shaw [2], Leo Tolstoy’s To The Working People [3] , Sun Yat Sen [4], Herbert Simon [5], and David Lloyd George. A follower of George, Lizzie Magie, created a board game called The Landlord’s Game in 1904 to demonstrate his theories. After further development this game led to the modern board game Monopoly. [6]

J. Frank Colbert, a newspaperman, a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives and later the mayor of Minden, joined the Georgist movement during 1927. During 1932, Colbert addressed the Henry George Congress at Memphis, Tennessee.

Also notable is Silvio Gesell‘s Freiwirtschaft [7], in which Gesell combined Henry George’s ideas about land ownership and rents with his own theory about the money system and interest rates and his successive development of Freigeld.

In his last book, Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community?, Martin Luther King, Jr referenced Henry George in support of a guaranteed minimum income.[8] George’s influence has ranged widely across the political spectrum. Noted progressives such as consumer rights advocate (and U.S. Presidential candidate) Ralph Nader [9] andCongressman Dennis Kucinich [10] have spoken positively about George in campaign platforms and speeches. His ideas have also received praise from conservative journalistsWilliam F. Buckley, Jr. [11] and Frank Chodorov [12], Fred E. Foldvary [13] and Stephen Moore [14]. The libertarian political and social commentator Albert Jay Nock[15] was also an avowed admirer, and wrote extensively on the Georgist economic and social philosophy.

Mason Gaffney, an American economist and a major Georgist critic of neoclassical economics, argued that neoclassical economics was designed and promoted by landowners and their hired economists to divert attention from George’s extremely popular philosophy that since land and resources are provided by nature, and their value is given by society, they – rather than labor or capital – should provide the tax base to fund government and its expenditures.[20]

The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [16], an incorporated “operating foundation,” also publishes copies of George’s work on economic reform and sponsors academic research into his policy proposals [17].

[edit]Economic contributions

George developed what he saw as a crucial feature of his own theory of economics in a critique of an illustration used by Frédéric Bastiat in order to explain the nature of interestand profit. Bastiat had asked his readers to consider James and William, both carpenters. James has built himself a plane, and has lent it to William for a year. Would James be satisfied with the return of an equally good plane a year later? Surely not! He’d expect a board along with it, as interest. The basic idea of a theory of interest is to understand why. Bastiat said that James had given William over that year “the power, inherent in the instrument, to increase the productivity of his labor,” and wants compensation for that increased productivity.

George did not accept this explanation. He wrote, “I am inclined to think that if all wealth consisted of such things as planes, and all production was such as that of carpenters — that is to say, if wealth consisted but of the inert matter of the universe, and production of working up this inert matter into different shapes, that interest would be but the robbery of industry, and could not long exist.” But some wealth is inherently fruitful, like a pair of breeding cattle, or a vat of grape juice soon to ferment into wine. Planes and other sorts of inert matter (and the most lent item of all—- money itself) earn interest indirectly, by being part of the same “circle of exchange” with fruitful forms of wealth such as those, so that tying up these forms of wealth over time incurs an opportunity cost.

George’s theory had its share of critiques. Austrian school economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, for example, expressed a negative judgment of George’s discussion of the carpenter’s plane. On page 339 of his treatise, Capital and Interest, he wrote:

In the first place, it is impossible to support his distinction of the branches of production into two classes, in one of which the vital forces of nature are supposed to constitute a special element which functions side by side with labour, and in the other of which this is not true. […] The natural sciences have long since proved to us that the cooperation of nature is universal. […] The muscular movements of the person using the plane would be of little use, if they did not have the assistance of the natural forces and properties of the plane iron.

Later, George argued that the role of time in production is pervasive. In “The Science of Political Economy”, he writes:[21]

[I]f I go to a builder and say to him, “In what time and at what price will you build me such and such a house?” he would, after thinking, name a time, and a price based on it. This specification of time would be essential…. This I would soon find if, not quarreling with the price, I ask him largely to lessen the time…. I might get the builder somewhat to lessen the time… ; but only by greatly increasing the price, until finally a point would be reached where he would not consent to build the house in less time no matter at what price. He would say [that the house just could not be built any faster]….The importance … of this principle that all production of wealth requires time as well as labor we shall see later on; but the principle that time is a necessary element in all production we must take into account from the very first.

According to Oscar B. Johannsen, “Since the very basis of the Austrian concept of value is subjective, it is apparent that George’s understanding of value paralleled theirs. However, he either did not understand or did not appreciate the importance of marginal utility.”[22]

Another spirited response came from British biologist T.H. Huxley in his article “Capital – the Mother of Labour,” published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. Huxley used the principles of energy science to undermine George’s theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive.

George’s early emphasis on the “productive forces of nature” is now dismissed even by otherwise Georgist authors.

[edit]See also

- Geolibertarianism

- Georgism

- Henry George Theorem

- Land Value Tax

- Left-libertarianism

- New York City mayoral elections

- Spaceship Earth

- Tammany Hall#1870-1900

- Charles Hall – An early precursor to Henry George

- History of the board game Monopoly

[edit]References

- Notes

- ^ Obituary, New York Times

- ^ http://www.guariscogallery.com/browse_by_artist.html?artist=595

- ^ “SINGLE TAXERS DINE JOHNSON; Medallion Made by Son of Henry George Presented to Cleveland’s Former Mayor”, The New York Times – May 31, 1910

- ^ Obituary – Th New York Times, May 4, 1897

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0210350/bio

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0313565/bio

- ^ http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss11_bioghist.html

- ^ Quoted in Nock, Albert Jay. “Henry George: Unorthodox American, Part I“.

- ^ According to his granddaughter Agnes de Mille, Progress and Poverty and its successors made Henry George the third most famous man in the USA, behind only Mark Twain andThomas Edison. [1]

- ^ “Henry George’s Death Abroad. London Papers Publish Long Sketches and Comment on His Career”. New York Times. October 30, 1897. Retrieved 2010-03-07. “The newspapers today are devoting much attention to the death of Henry George, the candidate of the Jeffersonian Democracy for the office of Mayor of Greater New York, publishing long sketches of his career and philosophical and economical theories.”

- ^ http://cooperativeindividualism.org/georgists_unitedstates-aa-al.html

- ^ http://cooperativeindividualism.org/abbott-lyman_on-henry-george.html

From Progressive to New Dealer: Frederic C. Howe and American Liberalism By Kenneth E. Miller

Chapters 4 and 5 from Kenneth Miller’s biography of Frederic C. Howe covering the pre-Tom Johnson period in the 1890s and the early 1900s.

Also includes material on Howe’s involvement with Goodrich Settlement.

Newton D. Baker by Philip W. Porter

Newton D. Baker, who was the official head of the Cleveland Democrats during the twenties and well into the thirties, was one of the few Cleveland political figures to become a nationally known statesman. He was called by President Wilson to become secretary of war before the United States got into World War I, and bore the entire responsibility for mobilizing an army from scratch, setting up the draft, and sending an expeditionary force of one million men to fight in France. After the war, drained emotionally and physically, he returned to Cleveland, but he remained active after Wilson’s death.

He was the unquestioned leader of Ohio Democrats at national conventions and kept such close contact with the national scene that in 1932, he had strong backing in both north and south for the presidential nomination. Had Roosevelt not been nominated on an early ballot, Baker stood a good chance of being chosen as a compromise candidate.

By any standard, Baker was one of the great men of his time. After he returned to Cleveland, he was always in demand to hold unpaid, nonpolitical civic jobs, and he continued to take a strong hand in Democratic party affairs, for he believed that good citizens ought to involve themselves in organized politics and government. He was revered by all newspaper men who came in contact with him, because he was simple, unpretentious, sincere and always approachable, a perfect example of the fact that the biggest men in government, industry, and the professions are the easiest to deal with. It isn’t always easy to get through their cordon of secretaries and assistants, but when you meet the big man face to face, he goes direct to the point and gives a straight answer. He will expect you to treat all confidential matters confidentially, but he puts on no airs, doesn’t give out the old double-talk. This was Newton D. Baker.

Baker’s unblemished principles made him the ideal teammate for the pragmatic Gongwer. Baker was always available to pronounce the principles, and take the high road, while Gongwer took the low road and attended to the patronage, the endorsements, the nuts and bolts of party management, without having to make speeches. Gongwer idolized Baker, but he also appreciated how useful Baker was to him as a party boss. Baker held the official position of chairman of the central committee, but Gongwer was chairman of the executive committee. Baker made statements and speeches. Gongwer made decisions and backed candidates. Baker approved completely of Gongwer’s decisions; he had no illusions about the necessity for a party boss. The Democrats were lucky to have them both; the Republicans had no such elder statesman as Baker. They left all the problems to Maschke, who made no pretense to being a statesman.

Baker came to Cleveland from Martinsburg, West Virginia, where he grew up as a Democrat; his ancestors had been Confederates. He joined Tom L. Johnson early, and was city solicitor, then law director. When Johnson died, Baker was the natural heir to run for mayor. When Wilson chose him for secretary of war, Baker was known as a pacifist. Wilson was not concerned about that; he needed a man of integrity.

When he returned to Cleveland, Baker was tired, middle-aged, disillusioned, and nearly broke. He had spent so many years in government that he had had no opportunity to accumulate money. So he organized a new law firm with two old Democratic friends — Joseph C. Hostetler, who had originally come from a farm in Tuscarawas County, and Thomas L. Sidlo, a bright young man who had been in Baker’s cabinet as service director. The firm soon attracted affluent corporate clients, and today is still one of the most influential and largest in Cleveland (although no one named Baker, Hostetler or Sidlo is still with the firm). PD editor Erie Hopwood was a close friend and client of Newton Baker; so was Elbert H. Baker (no relation), chairman of the Plain Dealer board.

Baker had a small, slight body, but a big mind. He was only a few inches more than five feet tall, was slender and lightweight. In addition to an amazing intellectual capacity, he had a deep, melodious voice and an uncanny ability to speak in complete, convincing sentences without a note in front of him. He simply knew exactly what he wanted to say, and how to say it; and he said it in the most mellow tones, which came out without the least bit of phoniness, unlike most orators.

Baker was a most approachable man, completely without deviousness or stuffiness. It was always easy to get to see him; all that was needed was to get his secretary to make a date. The secretary was usually a young law student or a newly graduated lawyer. (One of his most competent and popular secretaries was Henry S. Brainard, who later became city law director and after that, counsel for the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company.)

Baker was so short that he literally could, and would, curl up in a big office chair, and tuck one foot under him. He regularly smoked a big-bowled pipe. He was calm and even-tempered and went out of his way to be kind to young people. He was never without a book near at hand, usually some tome on history or philosophy. He was continually learning, and never wanted to waste a moment. He was often seen in a hotel corridor, waiting his turn to speak, quietly reading a book. He had plenty of books — not just law books, but reading-type books — in his office.

Everyone who heard Baker speak marveled at how he could extemporaneously come forth with the most cogent, well-reasoned, well-phrased arguments, without notes. He had such mental discipline that he arrayed his thoughts beforehand and knew how to express them for the most telling effect. He never prepared a text.

He was a tremendously effective courtroom lawyer. A1though he did not appear often in court, when he did it was worth paying admission to hear. One such time was when he defended Editor Louis B. Seltzer and Chief Editorial Writer Carlton K. Matson of the Press against a charge of contempt of court laid on them by Common Pleas Judge Fred P. Walther. The Press had severely rebuked Judge Walther for giving a light slap on the wrist to a defendant in a gambling case that involved Sheriff John M. Sulzmann (sheriffs were always in the grease with Cleveland newspapers). Walther took offense and cited the two editors for contempt. Baker, who was the Press’s lawyer as well as the Plain Dealer’s, appeared personally to defend them.

Baker’s cross-examination was superb, and his demolition of the judge’s reasons for citing the editors was icy, logical, and devastating. He went about as far as a lawyer could without saying in so many words that the judge was incompetent, ill-advised, or both. He made Walther seem like a pretentious fool. Finally, the irritated judge said, “Mr. Baker, are you expressing contempt for this court?” Baker, poker-faced, said firmly, “No, your honor, I am trying to conceal it.” (Walther found the editors guilty, but the court of appeals, after hearing Baker, freed the two.)

Baker used to enjoy telling of the sage advice he got from an old-timer, a brilliant courtroom lawyer, Matt Excell, when he was just a kid breaking in. Excell told him what emphasis to use in addressing a jury. “If the facts are on your side, argue the law,” advised Excell. “If the law is on your side, argue the facts. If neither the law nor the facts are on your side, confuse them, Newtie, confuse them.” Such smart tactics are still being used.

Baker was a man of broad culture. He was a music lover and supporter of the Cleveland Orchestra. (Mrs. Baker was an accomplished concert pianist.) He was deeply interested in education, and was offered the presidency of both Ohio State University and Western Reserve, but he preferred to stay with his law practice. He did serve as chairman of the board of trustees at Reserve, and was also on the board at Ohio State. The Newton D. Baker Hall now contains the dean’s and other administrative offices at Reserve, and there is a Baker Hall, a men’s dormitory, at Ohio State.

Cleveland lost its number one citizen when his heart gave out in 1937.

(His son, Newton D. (Jack) Baker II, has been administrator of the Lakeview Cemetery Association for several years, and his wife Phyllis, is active in Cleveland Orchestra and charitable efforts.)

Cleveland: Confused City on a Seesaw

by Philip W. Porter

retired executive editor of the Plain Dealer

1976

Courtesy of CSU Special Collections

Guilty? Of What? Speeches Before the Jury

Speeches given by Charles Ruthenberg, Alfred Wagenknecht and Charles Baker in front of the jury. They were accused of violating the Espionage Act in connection with a speech given at a rally on May 17, 1917.

A Ten Year’s War by Frederic Howe

Chapter from Confessions of a Reformer by Frederic Howe about Tom L Johnson

Socialist Party of Ohio– War and Free Speech

Article from the Ohio Historical Society Journal

Charles E. Ruthenberg: The Development of an American Communist, 1909-1927

Article from the Ohio Historical Society Journal

Collinwood Fire Memorial Book

From the Cleveland Public Library