SQUIRE-SANDERS AND THE SABOTAGE OF CLEVELAND

written June 2009

By Roldo Bartimole

This is a story of civic sabotage.

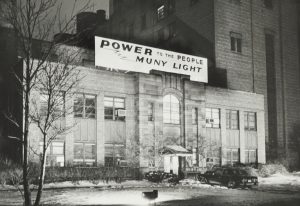

The desire for the private sector to damage, destroy and take over the Cleveland’s public electric power system reveals an important lesson in how power works in this or any community.

It also is instructive in the sense that you can apply these past lessons to today’s events and Squire-Sanders’s role in the medical mart.

This piece continues my attempt to review aspects of power that have been used in the community and to suggest how it is used today.

Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, Cleveland’s second largest law firm at the time, was a key player in this assault on public government.

Oddly, Squire-Sanders represented the city at the same it represented CEI, the private electric company. Guess whether the city or CEI got the best representation. The city claimed in court papers that the flow of crucial financial information went one way – to CEI, never to the city.

A lot of information about this situation became publicly available because the city eventually sued CEI. Court cases open private matters to public scrutiny.

Here’s the issue. Back in 1972 the city needed financing to help improve its electricity system. It wanted to borrow $9.8 million by letting bonds. Squire-Sanders served as its bond counsel.

The original legislation provided for sale through the City’s Sinking fund. If this didn’t work the city wanted to borrow via its own treasury account. This would allow the city to borrow from itself and at cheaper rates than on the private market.

However, an amendment to the city’s legislation, written by a Squire-Sanders attorney, stated that the bond issue could only be made on the open market. The amendment was attached to the legislation by then Council utilities chairman Frank Gaul, a close friend to CEI. Gaul in a court deposition admitted that he took gifts from CEI general counsel Lee Howley, a former city law director, and cooperated with the company in other ways.

Another Squire-Sanders lawyer wrote the original city legislation. It wanted the borrowing to avoid the private market.

“At that meeting the SS&D lawyer who wrote the ordinance was asked by the (city) law director to defend it, but, says the city, he “declined to defend his own work product and CEI’s crippling amendment was adopted and the amendment was approved…” I wrote from city documents at the time.

The move delayed the required borrowing for improvements until 1975. Just CEI’s desire. Ironically, the delayed bond issue was made through the city’s treasury account, as originally planned.

On another occasion during this period, the city attempted to buy backup power to avoid bad service. A CEI memo revealed that its executives, along with a Squire-Sanders partner, decided “The the company should refuse” to allow the city’s system to join a group that would give Muny Light cheaper power it vitally needed.

The city claimed that Squire-Sanders lawyers’ “representation of the city has endured so long, involved so many of its lawyers, and been so all pervasive it is very difficult to put any limits on their knowledge of the city’s affairs… Their inside knowledge… very likely exceeds that of the city itself.” All too true. Sabotage.

One of the milder charges against the law firm at the time was, “It would appear that Squire-Sanders used the management and financial information gleaned from its representation of the city for the benefit of CEI,” according to a brief that asked that Squire-Sanders be disqualified from representing CEI before the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission on an issue involving the city. Sabotage.

Here were some of the charges the city made against the law firm:

– It allowed amendments to legislation that it wrote to insure the city wouldn’t get needed financing.

– Advised CEI of a plan by which it could thwart the city’s attempt to get interconnections to needed electric power, although the law firm knew that the plan was likely illegal.

– Participated in CEI decisions that denied Muny Light cheaper power source.

Squire-Sanders, as today, injects itself into public matters. Indeed, it is used by many politicians as consultants. This puts the law firm in a central position on many public decisions, as Nance has been with the Browns situation and now the Medical Mart/Convention Center project.

One of the strategies businesses uses is to offer itself as helpmates to the city.

This was the case in 1967 when Ralph Besse, chairman of CEI, and a former Squire-Sanders law partner (upon retirement he went back to the law firm as a partner), formed the Inner City Action Committee to supposedly “help” Mayor Ralph Locher. The city was in serious trouble at the time with its urban renewal program.

Instead of helping, Besse administered a severe blow to Locher in a re-election year. First, he tried to foist one of his people on Locher to head the city’s urban renewal program. His odd choice was a former major general of the U. S. Army.

Locher balked. Besse turned on Locher. He went to the always accommodated Plain Dealer. The Pee Dee, as I have always liked to call the paper, did more than simply accommodate. It ran a top of Page One headline: “Besse’s Inner-City Group Quits Locher.” It was a powerful blow to a beleaguered Locher. Sabotage.

Locher did hit back. “I have not yet seen on real constructive action taken by the committee. So far we have heard some cries from them and they have made some demands on us. Where’s their action?” Locher’s point had validity.

Besse, of course, had an ulterior motive in embarrassing the mayor. His company wanted control of the city’s municipal light plant. But that never came into the public discussion. The media rarely, if ever, call corporate people on their self-interest in civic matters.

These efforts poisoned the relations between government and the private sector as dominated by corporate/legal interests in Cleveland.

This is an important point. These efforts damaged decision-making and leadership in this town. They built mistrust into all civic dealings.

Besse greatly admired favored Hitler general Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. He admired Rommel so much that he ordered his top executives to read him and adopt his methods.

War, not business.

One of his lines to his executives read, “The dead are lucky, it’s all over for them.” He had just finished reading ‘The Rommel Papers,” edited by B. H. Liddel Hart.

“There are so many places (in the book) where the parallel with business command is apparent that I have copied a few of the most interesting quotations… and have attached them,” wrote Besse to his executives.

One employee challenged him and he was dumped. He charged Besse wanted the company to operate as a war machine even though the company was actually a public utility with a “guaranteed profit.” I think this truth about it being a public utility whose profit was assured goes to the core of why CEI and the business community so wanted Muny out of the way. (See the full story in Point of View, Vol. 10, No. 22, May 22, 1978.)

The truth was both the city’s plant and CEI were not businesses in the true sense.

Here is one of the passages he cited for his executives:

“If there is anyone in a key position who appears to be expending less than the energy that could be properly be demanded of him, or who has no natural sense for practical problems of organization, then that man must be RUTHLESSLY REMOVED.” (My emphasis).

The fight by the city to maintain its electric system is a classic case of public vs. private interests. It should be studied in business economics classes. It goes to the core of many ideological problems being examined now on the national stage.

We will see how CEI and Squire-Sanders tried to destroy the city’s electric system over a number of years and how it was caught breaking the law by the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and how a federal lawsuit, in two trials, failed because of a Cleveland judge’s bias permeated the courtroom.