WMMS Plain Dealer Sunday Magazine piece by Joe Crea 2/19/1978

http://teachingcleveland.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Joe-Rocks-Out-with-the-Buzzard-Nuclear-Army.pdf

www.teachingcleveland.org

WMMS Plain Dealer Sunday Magazine piece by Joe Crea 2/19/1978

http://teachingcleveland.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Joe-Rocks-Out-with-the-Buzzard-Nuclear-Army.pdf

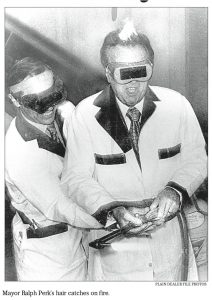

A historic look at former Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk, the ‘hottest mayor in the country’ Cleveland.com Nov 2, 2017

The link is here

Kent State Library Special Collections Site

Kent State University was placed into the international spotlight on May 4, 1970, after 13 students were shot by members of the Ohio National Guard at a student demonstration. Four students were killed and nine others were wounded, including one who was permanently paralyzed from his injury. The May 4 Collection, established by the Kent State University Libraries in 1970, includes over 300 cubic feet of primary sources related to the Kent State shootings and their aftermath. The collection is open to the public and is used by researchers from around the world.

Democratizing Cleveland: The Rise and Fall of Community Organizing in Cleveland, Ohio 1975-1985

by Randy Cunningham

The pdf is here

If above link does not work, try this

The lecture that supports this is here

SQUIRE-SANDERS AND THE SABOTAGE OF CLEVELAND

written June 2009

By Roldo Bartimole

This is a story of civic sabotage.

The desire for the private sector to damage, destroy and take over the Cleveland’s public electric power system reveals an important lesson in how power works in this or any community.

It also is instructive in the sense that you can apply these past lessons to today’s events and Squire-Sanders’s role in the medical mart.

This piece continues my attempt to review aspects of power that have been used in the community and to suggest how it is used today.

Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, Cleveland’s second largest law firm at the time, was a key player in this assault on public government.

Oddly, Squire-Sanders represented the city at the same it represented CEI, the private electric company. Guess whether the city or CEI got the best representation. The city claimed in court papers that the flow of crucial financial information went one way – to CEI, never to the city.

A lot of information about this situation became publicly available because the city eventually sued CEI. Court cases open private matters to public scrutiny.

Here’s the issue. Back in 1972 the city needed financing to help improve its electricity system. It wanted to borrow $9.8 million by letting bonds. Squire-Sanders served as its bond counsel.

The original legislation provided for sale through the City’s Sinking fund. If this didn’t work the city wanted to borrow via its own treasury account. This would allow the city to borrow from itself and at cheaper rates than on the private market.

However, an amendment to the city’s legislation, written by a Squire-Sanders attorney, stated that the bond issue could only be made on the open market. The amendment was attached to the legislation by then Council utilities chairman Frank Gaul, a close friend to CEI. Gaul in a court deposition admitted that he took gifts from CEI general counsel Lee Howley, a former city law director, and cooperated with the company in other ways.

Another Squire-Sanders lawyer wrote the original city legislation. It wanted the borrowing to avoid the private market.

“At that meeting the SS&D lawyer who wrote the ordinance was asked by the (city) law director to defend it, but, says the city, he “declined to defend his own work product and CEI’s crippling amendment was adopted and the amendment was approved…” I wrote from city documents at the time.

The move delayed the required borrowing for improvements until 1975. Just CEI’s desire. Ironically, the delayed bond issue was made through the city’s treasury account, as originally planned.

On another occasion during this period, the city attempted to buy backup power to avoid bad service. A CEI memo revealed that its executives, along with a Squire-Sanders partner, decided “The the company should refuse” to allow the city’s system to join a group that would give Muny Light cheaper power it vitally needed.

The city claimed that Squire-Sanders lawyers’ “representation of the city has endured so long, involved so many of its lawyers, and been so all pervasive it is very difficult to put any limits on their knowledge of the city’s affairs… Their inside knowledge… very likely exceeds that of the city itself.” All too true. Sabotage.

One of the milder charges against the law firm at the time was, “It would appear that Squire-Sanders used the management and financial information gleaned from its representation of the city for the benefit of CEI,” according to a brief that asked that Squire-Sanders be disqualified from representing CEI before the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission on an issue involving the city. Sabotage.

Here were some of the charges the city made against the law firm:

– It allowed amendments to legislation that it wrote to insure the city wouldn’t get needed financing.

– Advised CEI of a plan by which it could thwart the city’s attempt to get interconnections to needed electric power, although the law firm knew that the plan was likely illegal.

– Participated in CEI decisions that denied Muny Light cheaper power source.

Squire-Sanders, as today, injects itself into public matters. Indeed, it is used by many politicians as consultants. This puts the law firm in a central position on many public decisions, as Nance has been with the Browns situation and now the Medical Mart/Convention Center project.

One of the strategies businesses uses is to offer itself as helpmates to the city.

This was the case in 1967 when Ralph Besse, chairman of CEI, and a former Squire-Sanders law partner (upon retirement he went back to the law firm as a partner), formed the Inner City Action Committee to supposedly “help” Mayor Ralph Locher. The city was in serious trouble at the time with its urban renewal program.

Instead of helping, Besse administered a severe blow to Locher in a re-election year. First, he tried to foist one of his people on Locher to head the city’s urban renewal program. His odd choice was a former major general of the U. S. Army.

Locher balked. Besse turned on Locher. He went to the always accommodated Plain Dealer. The Pee Dee, as I have always liked to call the paper, did more than simply accommodate. It ran a top of Page One headline: “Besse’s Inner-City Group Quits Locher.” It was a powerful blow to a beleaguered Locher. Sabotage.

Locher did hit back. “I have not yet seen on real constructive action taken by the committee. So far we have heard some cries from them and they have made some demands on us. Where’s their action?” Locher’s point had validity.

Besse, of course, had an ulterior motive in embarrassing the mayor. His company wanted control of the city’s municipal light plant. But that never came into the public discussion. The media rarely, if ever, call corporate people on their self-interest in civic matters.

These efforts poisoned the relations between government and the private sector as dominated by corporate/legal interests in Cleveland.

This is an important point. These efforts damaged decision-making and leadership in this town. They built mistrust into all civic dealings.

Besse greatly admired favored Hitler general Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. He admired Rommel so much that he ordered his top executives to read him and adopt his methods.

War, not business.

One of his lines to his executives read, “The dead are lucky, it’s all over for them.” He had just finished reading ‘The Rommel Papers,” edited by B. H. Liddel Hart.

“There are so many places (in the book) where the parallel with business command is apparent that I have copied a few of the most interesting quotations… and have attached them,” wrote Besse to his executives.

One employee challenged him and he was dumped. He charged Besse wanted the company to operate as a war machine even though the company was actually a public utility with a “guaranteed profit.” I think this truth about it being a public utility whose profit was assured goes to the core of why CEI and the business community so wanted Muny out of the way. (See the full story in Point of View, Vol. 10, No. 22, May 22, 1978.)

The truth was both the city’s plant and CEI were not businesses in the true sense.

Here is one of the passages he cited for his executives:

“If there is anyone in a key position who appears to be expending less than the energy that could be properly be demanded of him, or who has no natural sense for practical problems of organization, then that man must be RUTHLESSLY REMOVED.” (My emphasis).

The fight by the city to maintain its electric system is a classic case of public vs. private interests. It should be studied in business economics classes. It goes to the core of many ideological problems being examined now on the national stage.

We will see how CEI and Squire-Sanders tried to destroy the city’s electric system over a number of years and how it was caught breaking the law by the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and how a federal lawsuit, in two trials, failed because of a Cleveland judge’s bias permeated the courtroom.

From Cleveland State Special Collections

Collection/Web Exhibit: The Cleveland Memory Project

Program Length: 17:30 min.

Footage courtesy of The Northeast Ohio Broadcast Archives (NOBA) at the John Carroll University Department of Communications. Special thanks to Dr. Alan Stephenson and Lisa Lewis for their assistance.

From Cleveland State Univ Special Collections

| Title | More than a bus ride : the desegregation of the Cleveland Public Schools |

| Creator | Stevens, Leonard B. (Leonard Berry), 1938 – Office on School Monitoring and Community Relations (Cleveland, Ohio) Weinberg, Meyer, 1920-2002 |

| Description | “On June 13, 14, and 16, 1984, the Advisory Commission of the monitoring office held public hearings in the hope that the desegregation process would be illuminated, and it was. The hearings brought forthpeople who added new light to the question: How are the Cleveland schools different as a result of thedesegregation process? This document, which contains a selection of the comments made at thesehearings, manifests the Commission’s collective gratitude to the dozens of individuals who came to ourhearings and spoke so candidly.” Leonard B. Stevens, Office on Sch. Monitoring and Cmty. Relations 1(Meyer Weinberg ed. 1985). |

| Date Original | 1985-09 |

| Kent State shootings | |

|---|---|

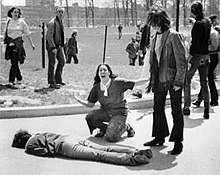

John Filo‘s iconic Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, a 14-year-old runaway, kneeling in anguish over the body ofJeffrey Miller minutes after he was shot by theOhio National Guard

|

|

| Location | Kent, Ohio, USA |

| Date | May 4, 1970 12:24 pm[1] (Eastern) |

| Target | Kent State Universitystudents |

| Weapon(s) | M1 Garand rifles |

| Deaths | 4 |

| Injured (non-fatal) | 9 |

| Perpetrators | Ohio Army National Guard |

The Kent State shootings—also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre[2][3][4]—occurred atKent State University in the U.S. city of Kent, Ohio, and involved the shooting of unarmed college students by theOhio National Guard on Monday, May 4, 1970. The guardsmen fired 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.[5]

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced in a television address on April 30. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.[6][7]

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of four million students,[8] and the event further affected the public opinion—at an already socially contentious time—over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.[9]

Contents[hide] |

Richard Nixon had been elected President in 1968, promising to end the Vietnam War. In November 1969, the My Lai Massacre by American troops of between 347 and 504 civilians in a Vietnamese village was exposed, leading to increased public opposition in the United States to the war. In addition, the following month saw the first draft lottery instituted since World War II. The war had appeared to be winding down throughout 1969, so the new invasion of Cambodia angered those who believed it only exacerbated the conflict. Many young people, including college students and teachers, were concerned about being drafted to fight in a war that they strongly opposed. The expansion of that war into another country appeared to them to have increased that risk. Across the country, campuses erupted in protests in what Time called “a nation-wide student strike”, setting the stage for the events of early May 1970.

President Nixon announced to the nation that the “Cambodian Incursion” had been launched by United States combat forces.

At Kent State University a demonstration with about 500 students[10] was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 pm, another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to “bring the war home.” As a symbolic protest to Nixon’s decision to send troops, a group of students watched a graduate student burning a copy of the U.S. Constitution while another student burned his draft card.

Trouble exploded in town around midnight when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at cars and breaking downtown store fronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism and looting.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd had already lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared astate of emergency, called Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes‘ office to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.[7]

City officials and downtown businesses received threats while rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances.[7] The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 pm, but the guard did not arrive into town that evening until around 10 pm. A large demonstration was already under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) building[11] was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended and no one was injured in the fire.[12] More than a thousand protesters surrounded the building and cheered its burning. Several Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called in because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it.[13][14][15] The National Guard made numerous arrests and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.[16]

During press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk[17] and called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio. “We’ve seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police, and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we’re going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We’re not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They’re worse than thebrown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes”, Rhodes said. “They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we’re up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.”[18] Rhodes can be heard in the recording of his speech yelling and pounding his fists on the desk.[19][20]

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.[7]

During the day some students came into downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, which met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8:00 pm, another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 pm the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main Streets, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and President White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.[21]

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts an estimated 2,000 people gathered[22] on the university’s Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus’s iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.[23]

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice,[24] riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read them an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus Patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.[7]

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard’s line, to chants of “Pigs off campus!” The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on theirM1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of The Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading down toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about ten minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated off to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 ft (46 m) to 225 ft (69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others (perhaps 35 or 40) were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of the guardsmen knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. For a few moments, several guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About ten minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back down into the Commons.

At 12:24 pm,[1] according to eyewitnesses, a Sgt. Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the students with his .45 pistol.[25] A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their M1 Garand rifles at the students. In all, 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using a final total of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in the New York Times that “it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer.”[26] The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

The Adjutant General of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which itself remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that “triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State.” The President’s Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that “the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.”[27]

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest, and the other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 225 feet (69 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Two men who were present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they’re not going to shoot, they can’t do that. If they are going to shoot, it’s going to be blank.[28]

Unidentified speaker 2:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit. He stumbled and fell, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

As this student fell behind the car, I saw another student go down, next to the curb, on the far side of the automobile, maybe 25 or 30 yards from where I was lying. It was maybe 25, 30, 35 seconds of sporadic firing.

The firing stopped. I lay there maybe 10 or 15 seconds. I got up, I saw four or five students lying around the lot. By this time, it was like mass hysteria. Students were crying, they were screaming for ambulances. I heard some girl screaming, “They didn’t have blank, they didn’t have blank,” no, they didn’t.[29]

Immediately after the shootings, many angry students were ready to launch an all-out attack on the National Guard. Many faculty members, led by geology professor and faculty marshal Glenn Frank, pleaded with the students to leave the Commons and to not give in to violent escalation:

I don’t care whether you’ve never listened to anyone before in your lives. I am begging you right now. If you don’t disperse right now, they’re going to move in, and it can only be a slaughter. Would you please listen to me? Jesus Christ, I don’t want to be a part of this … ![30]

After 20 minutes of speaking, the students left the Commons, as ambulance personnel tended to the wounded, and the Guard left the area. Professor Frank’s son, also present that day, said, “He absolutely saved my life and hundreds of others”.[31]

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

In the Presidents Commission on Campus Unrest (pp. 273–274)[32] they mistakenly list Thomas V. Grace, who is Thomas Mark Grace’s father, as the Thomas Grace injured.

All those shot were students in good standing at the university.[32]

Although initial newspaper reports had inaccurately stated that a number of National Guard members had been killed or seriously injured, only one Guardsman, Sgt. Lawrence Shafer, was injured seriously enough to require medical treatment, approximately 10 to 15 minutes prior to the shootings.[33] Shafer is also mentioned in a memo from November 15, 1973. The FBI memo was prepared by the Cleveland Office and is referred to by Field Office file # 44-703. It reads as follows:

Upon contacting appropriate officers of the Ohio National Guard at Ravenna and Akron, Ohio, regarding ONG radio logs and the availability of service record books, the respective ONG officer advised that any inquiries concerning the Kent State University incident should be direct to the Adjutant General, ONG, Columbus, Ohio. Three persons were interviewed regarding a reported conversation by Sgt Lawrence Shafer, ONG, that Shafer had bragged about “taking a bead” on Jeffrey Miller at the time of the ONG shooting and each interviewee was unable to substantiate such a conversation.

In an interview broadcast in 1986 on the ABC News documentary series Our World, Shafer identified the person that he fired at as Joseph Lewis.

Photographs of the dead and wounded at Kent State that were distributed in newspapers and periodicals worldwide amplified sentiment against the United States’ invasion of Cambodia and the Vietnam War in general. In particular, the camera of Kent State photojournalism student John Filo captured a fourteen-year old runaway, Mary Ann Vecchio, screaming over the body of the dead student, Jeffrey Miller, who had been shot in the mouth. The photograph, which won a Pulitzer Prize, became the most enduring image of the events, and one of the most enduring images of the anti-Vietnam War movement.[citation needed]

The shootings led to protests on college campuses throughout the United States, and a student strike, causing more than 450 campuses across the country to close with both violent and non-violent demonstrations.[8] A common sentiment was expressed by students at New York University with a banner hung out of a window which read, “They Can’t Kill Us All.”[34] On May 8, eleven people were bayonetted at the University of New Mexico by the New Mexico National Guard in a confrontation with student protesters.[35] Also on May 8, an antiwar protest at New York’s Federal Hall held at least partly in reaction to the Kent State killings was met with a counter-rally of pro-Nixon construction workers (organized by Peter J. Brennan, later appointed U.S. Labor Secretary by President Nixon), resulting in the “Hard Hat Riot“.

Just five days after the shootings, 100,000 people demonstrated in Washington, D.C., against the war and the killing of unarmed student protesters. Ray Price, Nixon’s chief speechwriter from 1969–1974, recalled the Washington demonstrations saying, “The city was an armed camp. The mobs were smashing windows, slashing tires, dragging parked cars into intersections, even throwing bedsprings off overpasses into the traffic down below. This was the quote, student protest. That’s not student protest, that’s civil war.”[8] Not only was Nixon taken to Camp David for two days for his own protection, but Charles Colson (Counsel to President Nixon from 1969 to 1973) stated that the military was called up to protect the administration from the angry students; he recalled that “The 82nd Airbornewas in the basement of the executive office building, so I went down just to talk to some of the guys and walk among them, and they’re lying on the floor leaning on their packs and their helmets and their cartridge belts and their rifles cocked and you’re thinking, ‘This can’t be the United States of America. This is not the greatest free democracy in the world. This is a nation at war with itself.'”[8]

Shortly after the shootings took place, the Urban Institute conducted a national study that concluded the Kent State shooting was the single factor causing the only nationwide student strike in U.S. history; over 4 million students protested and over 900 American colleges and universities closed during the student strikes. The Kent State campus remained closed for six weeks.

President Nixon and his administration’s public reaction to the shootings was perceived by many in the anti-war movement as callous. Then National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger said the president was “pretending indifference.” Stanley Karnow noted in his Vietnam: A History that “The [Nixon] administration initially reacted to this event with wanton insensitivity. Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler, whose statements were carefully programmed, referred to the deaths as a reminder that ‘when dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.'” Three days before the shootings, Nixon himself had talked of “bums” who were antiwar protestors on US campuses,[36] to which the father of Allison Krause stated on national TV “My child was not a bum.”[37]

A Gallup Poll taken immediately after the shootings showed that 58 percent of respondents blamed the students, 11 percent blamed the National Guard and 31 percent expressed no opinion.[38]

Karnow further documented that at 4:15 am on May 9, 1970, the president met about 30 student dissidents conducting a vigil at the Lincoln Memorial, whereupon Nixon “treated them to a clumsy and condescending monologue, which he made public in an awkward attempt to display his benevolence.” Nixon had been trailed by White House Deputy for Domestic Affairs Egil Krogh, who saw it differently than Karnow, saying, “I thought it was a very significant and major effort to reach out.”[8] In any regard, neither side could convince the other and after meeting with the students, Nixon expressed that those in the anti-war movement were the pawns of foreign communists.[8] After the student protests, Nixon asked H. R. Haldeman to consider the Huston Plan, which would have used illegal procedures to gather information on the leaders of the anti-war movement. Only the resistance of J. Edgar Hoover stopped the plan.[8]

On May 14, ten days after the Kent State shootings, two black students were killed (and 12 wounded) by police at Jackson State University under similar circumstances – the Jackson State killings – but that event did not arouse the same nationwide attention as the Kent State shootings.[39]

There was wide discussion as to whether these were legally justified shootings of American citizens, and whether the protests or the decisions to ban them were constitutional. These debates served to further galvanize uncommitted opinion by the terms of the discourse. The term “massacre” was applied to the shootings by some individuals and media sources, as it had been used for the Boston Massacre of 1770, in which five were killed and several more wounded.[2][3][4]

On June 13, 1970, as a consequence of the killings of protesting students at Kent State and Jackson State, President Nixon established the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, known as the Scranton Commission, which he charged to study the dissent, disorder, and violence breaking out on college and university campuses across the nation.[40][41]

The Commission issued its findings in a September 1970 report that concluded that the Ohio National Guard shootings on May 4, 1970, were unjustified. The report said:

Even if the guardsmen faced danger, it was not a danger that called for lethal force. The 61 shots by 28 guardsmen certainly cannot be justified. Apparently, no order to fire was given, and there was inadequate fire control discipline on Blanket Hill. The Kent State tragedy must mark the last time that, as a matter of course, loaded rifles are issued to guardsmen confronting student demonstrators.

In September 1970, twenty-four students and one faculty member were indicted on charges connected with the May 4 demonstration at the ROTC building fire three days before. These individuals, who had been identified from photographs, became known as the “Kent 25.” Five cases, all related to the burning of the ROTC building, went to trial; one non-student defendant was convicted on one charge and two other non-students pleaded guilty. One other defendant was acquitted, and charges were dismissed against the last. In December 1971, all charges against the remaining twenty were dismissed for lack of evidence.[42][43]

Eight of the guardsmen were indicted by a grand jury. The guardsmen claimed to have fired in self-defense, a claim that was generally accepted by the criminal justice system. In 1974 U.S. District Judge Frank Battisti dismissed charges against all eight on the basis that the prosecution’s case was too weak to warrant a trial.[7]

Larry Shafer, a guardsman who said he fired during the shootings and was one of those charged, told the Kent-Ravenna Record-Courier newspaper in May 2007: “I never heard any command to fire. That’s all I can say on that.” Shafer—a Ravenna city councilman and former fire chief—went on to say, “That’s not to say there may not have been, but with all the racket and noise, I don’t know how anyone could have heard anything that day.” Shafer also went on to say that “point” would not have been part of a proper command to open fire.

Civil actions were also attempted against the guardsmen, the State of Ohio, and the president of Kent State. The federal court civil action for wrongful death and injury, brought by the victims and their families against Governor Rhodes, the President of Kent State, and the National Guardsmen, resulted in unanimous verdicts for all defendants on all claims after an eleven-week trial.[44] The judgment on those verdicts was reversed by the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on the ground that the federal trial judge had mishandled an out-of-court threat against a juror. On remand, the civil case was settled in return for payment of a total of $675,000 to all plaintiffs by the State of Ohio[45] (explained by the State as the estimated cost of defense) and the defendants’ agreement to state publicly that they regretted what had happened:

In retrospect, the tragedy of May 4, 1970 should not have occurred. The students may have believed that they were right in continuing their mass protest in response to the Cambodian invasion, even though this protest followed the posting and reading by the university of an order to ban rallies and an order to disperse. These orders have since been determined by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to have been lawful.

Some of the Guardsmen on Blanket Hill, fearful and anxious from prior events, may have believed in their own minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

We devoutly wish that a means had been found to avoid the May 4th events culminating in the Guard shootings and the irreversible deaths and injuries. We deeply regret those events and are profoundly saddened by the deaths of four students and the wounding of nine others which resulted. We hope that the agreement to end the litigation will help to assuage the tragic memories regarding that sad day.

In the succeeding years, many in the anti-war movement have referred to the shootings as “murders,” although no criminal convictions were obtained against any National Guardsman. In December 1970, journalist I. F. Stone wrote the following:

To those who think murder is too strong a word, one may recall that even Agnew three days after the Kent State shootings used the word in an interview on the David Frost show in Los Angeles. Agnew admitted in response to a question that what happened at Kent State was murder, “but not first degree” since there was – as Agnew explained from his own training as a lawyer – “no premeditation but simply an over-response in the heat of anger that results in a killing; it’s a murder. It’s not premeditated and it certainly can’t be condoned.”[46]

The Kent State incident forced the National Guard to re-examine its methods of crowd control. The only equipment the guardsmen had to disperse demonstrators that day were M1 Garand rifles loaded with .30-06 FMJ ammunition, 12 Ga. pump shotguns, and bayonets, and CS gas grenades. In the years that followed, the U.S. Army began developing less lethal means of dispersing demonstrators (such as rubber bullets), and changed its crowd control and riot tactics to attempt to avoid casualties amongst the demonstrators. Many of the crowd-control changes brought on by the Kent State events are used today by police and military forces in the United States when facing similar situations, such as the 1992 Los Angeles Riots and civil disorder during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

One outgrowth of the events was the Center for Peaceful Change established at Kent State University in 1971 “as a living memorial to the events of May 4, 1970.”[47] Now known as The Center for Applied Conflict Management (CACM), it developed one of the earliest conflict resolution undergraduate degree programs in the United States. The Institute for the Study and Prevention of Violence, an interdisciplinary program dedicated to violence prevention, was established in 1998.

According to FBI reports, one part-time student, Terry Norman, was already noted by student protesters as an informant for both campus police and the Akron FBIbranch. Norman was present during the May 4 protests, taking photographs to identify student leaders,[48] while carrying a sidearm and wearing a gas mask.

In 1970, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover responded to questions from then-Congressman John Ashbrook by denying that Norman had ever worked for the FBI, a statement Norman himself disputed.[49] On August 13, 1973, Indiana Senator Birch Bayh sent a memo to then-governor of Ohio John J. Gilligan suggesting that Norman may have fired the first shot, based on testimony he [Bayh] received from guardsmen who claimed that a gunshot fired from the vicinity of the protesters instigated the Guard to open fire on the students.[50]

Throughout the 40 years since the shootings, debate has continued on about the events of May 4, 1970.[51][52]

Two of the survivors have died: James Russell on June 23, 2007;[53] and Robert Stamps in June 2008.[54]

In 2007 Alan Canfora, one of the wounded, located a copy of a tape of the shootings in a library archive. The original 30-minute reel-to-reel tape was made by Terry Strubbe, a Kent State communications student who turned on his recorder and put its microphone in his dorm window overlooking the campus. A 2010 audio analysis of a tape recording of the incident by Stuart Allen and Tom Owen, who were described by the Cleveland Plain Dealer as “nationally respected forensic audio experts,” concluded that the guardsmen were given an order to fire. It is the only known recording to capture the events leading up to the shootings. According to the Plain Dealer description of the enhanced recording, a male voice yells “Guard!” Several seconds pass. Then, “All right, prepare to fire!” “Get down!,” someone shouts urgently, presumably in the crowd. Finally, “Guard! . . . ” followed two seconds later by a long, booming volley of gunshots. The entire spoken sequence lasts 17 seconds. Further analysis of the audiotape revealed that four pistol shots and a violent confrontation occurred approximately 70 seconds before the National Guard opened fire. According to The Plain Dealer, this new analysis raised questions about the role of Terry Norman, a Kent State student who was an FBI informant and known to be carrying a pistol during the disturbance. Alan Canfora said it was premature to reach any conclusions.[55][56]

In April 2012 the United States Department of Justice determined that there were “insurmountable legal and evidentiary barriers” to reopening the case. Also in 2012 the FBI concluded the Strubbe tape was inconclusive because what has been described as pistol shots may have been slamming doors and that voices heard were unintelligible. Despite this, organizations of survivors and current Kent State students continue to believe the Strubbe tape proves the Guardsmen were given a military order to fire and are petitioning State of Ohio and U.S. Government officials to reopen the case using independent analysis. The organizations do not desire to prosecute or sue individual guardsmen believing they are also victims.[57][58]

|

Kent State Shootings Site

|

|

|

|

| Location: | .5 mi. SE of the intersection of E. Main St. and S. Lincoln St., Kent, Ohio |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: | 41.150181°N 81.343383°WCoordinates: 41.150181°N 81.343383°W |

| Area: | 17.24 acres (6.98 ha)[60] |

| Governing body: | Private |

| NRHP Reference#: | 10000046[59] |

| Added to NRHP: | February 23, 2010[59] |

Each May 4 from 1971 to 1975 the Kent State University administration sponsored an official commemoration of the events. Upon the university’s announcement in 1976 that it would no longer sponsor such commemorations, the May 4 Task Force, a group made up of students and community members, was formed for this purpose. The group has organized a commemoration on the university’s campus each year since 1976; events generally include a silent march around the campus, a candlelight vigil, a ringing of the Victory Bell in memory of those killed and injured, speakers (always including eyewitnesses and family members), and music.

On May 12, 1977, a tent city was erected and maintained for a period of more than 60 days by a group of several dozen protesters on the Kent State campus. The protesters, led by the May 4 Task Force but also including community members and local clergy, were attempting to prevent the university from erecting a gymnasium annex on part of the site where the shootings occurred seven years earlier, which they believed would alter and obscure the historical event. Law enforcement finally brought the tent city to an end on July 12, 1977, after the forced removal and arrest of 193 people. The event gained national press coverage and the issue was taken to the U.S. Supreme Court.[61]

In 1990, twenty years after the shootings, a memorial commemorating the events of May 4 was dedicated on the campus on a 2.5 acre (10,000 m²) site overlooking the University’s Commons where the student protest took place.[62] Even the construction of the monument became controversial and, in the end, only 7% of the design was constructed. The memorial itself does not contain the names of those killed or wounded in the shooting; under pressure, the university agreed to install a plaque near it with the names.[63][64]

In 1999, at the urging of relatives of the four students killed in 1970, the university constructed an individual memorial for each of the students in the parking lot between Taylor and Prentice halls. Each of the four memorials is located on the exact spot where the student fell, mortally wounded. They are surrounded by a raised rectangle of granite[65]featuring six lightposts approximately four feet high, with the student’s name engraved on a triangular marble plaque in one corner.[66]

George Segal’s 1978 cast-from-life bronze sculpture, In Memory of May 4, 1970, Kent State: Abraham and Isaac was commissioned for the Kent State campus by a private fund for public art,[67] but was refused by the university administration who deemed its subject matter (the biblical Abraham poised to sacrifice his son Isaac) too controversial. The sculpture was accepted in 1979 by Princeton University, and currently resides there between the university chapel and library.[68]

An earlier work of land art, Partially Buried Woodshed,[69] was produced on the Kent State campus by Robert Smithson in January 1970.[70] Shortly after the events, an inscription was added that recontextualized the work in such a way that it came to be associated by some with the event.

In 2004, a simple stone memorial was erected at Plainview-Old Bethpage John F. Kennedy High School in Plainview, New York, which Jeffrey Miller had attended.

On May 3, 2007, just prior to the yearly commemoration, an Ohio Historical Society marker was dedicated by KSU president Lester Lefton. It is located between Taylor Hall and Prentice Hall between the parking lot and the 1990 memorial.[71] Also in 2007, a memorial service was held at Kent State in honor of James Russell, one of the wounded, who died in 2007 of a heart attack.[72]

In 2008, Kent State University announced plans to construct a May 4 Visitors’ Center in a room in Taylor Hall.[73]

A 17.24-acre (6.98 ha) area was listed as “Kent State Shootings Site” on the National Register of Historic Places on February 23, 2010.[59] Places normally cannot be added to the Register until they have been significant for at least fifty years, and only cases of “exceptional importance” can be added sooner.[74] The entry was announced as the featured listing in the National Park Service‘s weekly list of March 5, 2010.[75] Contributing resources in the site are: Taylor Hall, the Victory Bell, Lilac Lane and Boulder Marker, The Pagoda, Solar Totem, and the Prentice Hall Parking Lot.[60] The National Park Service stated the site “is considered nationally significant given its broad effects in causing the largest student strike in United States history, affecting public opinion about the Vietnam War, creating a legal precedent established by the trials subsequent to the shootings, and for the symbolic status the event has attained as a result of a government confronting protesting citizens with unreasonable deadly force.”[9]

Every year on the anniversary of the shootings, notably on the 40th anniversary in 2010, students and others who were present share remembrances of the day and the impact it has had on their lives. Among them are Nick Saban, head coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide football team who was a freshman in 1970;[76]surviving student Tom Grace, who was shot in the foot;[77] Kent State faculty member Jerry Lewis;[78] photographer John Filo;[31] and others.

The best known popular culture response to the deaths at Kent State was the protest song “Ohio“, written by Neil Young for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. The song was written, recorded, and preliminary pressings (acetates) were rushed to major radio stations, although the group already had a hit song, “Teach Your Children“, on the charts at the time. Within two-and-a-half weeks of the Kent State shootings, “Ohio” was receiving national airplay. Crosby, Stills, and Nashvisited the Kent State campus for the first time on May 4, 1997, where they performed the song for the May 4 Task Force’s 27th annual commemoration. The B-side of the single release was Stephen Stills’ anti-Vietnam War anthem “Find the Cost of Freedom”.

There are a number of lesser known musical tributes, including the following:

| Dennis Kucinich | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio‘s 10th district |

|

| In office January 3, 1997 – January 3, 2013 |

|

| Preceded by | Martin Hoke |

| Succeeded by | Mike Turner |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 23rd district |

|

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 2, 1997 |

|

| Preceded by | Anthony Sinagra |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Sweeney |

| 53rd Mayor of Cleveland | |

| In office January 26, 1978 – November 6, 1979 |

|

| Preceded by | Ralph J. Perk |

| Succeeded by | George Voinovich |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dennis John Kucinich October 8, 1946 Cleveland, Ohio |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Kucinich (divorced) Sandra Lee McCarthy (1977–1986; divorced) Elizabeth Kucinich (2005–present) |

| Children | Jackie Kucinich |

| Residence | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Alma mater | Cleveland State University Case Western Reserve University |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Dennis John Kucinich (/kuːˈsɪnɪtʃ/; born October 8, 1946) was a U.S. Representative, serving from 1997 to 2013. He was also a candidate for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States in the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections.[1]

He was a member of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.

From 1977 to 1979, Kucinich served as the 53rd mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, a tumultuous term in which he survived a recall election and was successful in a battle against selling the municipal electric utility before being defeated for reelection by George Voinovich.

Through his various governmental positions and campaigns, Kucinich attracted attention for consistently delivering “the strongest liberal” perspective.[2] This perspective has been shown by his actions, such as bringing articles of impeachment against President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney, and being the only Democratic candidate in the 2008 election to have voted against invading Iraq,[3] although eventual nominee Barack Obama had also opposed the Iraq War at the time it was started, even though he had not been in Congress at the time.

Because of redistricting following the 2010 state elections, Ohio’s 9th congressional district absorbed part ofCuyahoga County, abolishing Kucinich’s district and pitted him against 9th district incumbent Marcy Kaptur in the 2012 Democratic primary, which he lost.[4][5][6][7][8] After serving out the rest of his term, it was announced in mid-January 2013 that the former congressman would become a political analyst and regular contributor on the Fox News Channel, appearing on programs such as The O’Reilly Factor.[9]

Kucinich was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on October 8, 1946, as the eldest of the seven children of Virginia (née Norris) and Frank J. Kucinich.[10][11] His father, a truck driver, was of Croat ancestry; his Irish American mother was ahomemaker.[12] Growing up, his family moved 21 times and Dennis was often charged with the responsibility of finding apartments they could afford.[13]

He attended Cleveland State University from 1967 to 1970.[14] In 1973, he graduated from Case Western Reserve University with both a Bachelor and a Master of Arts degree in speech and communication.[15] Kucinich was baptized aRoman Catholic.[14] Kucinich married Sandra Lee McCarthy in 1977; they had a daughter named Jackie in 1981 and divorced in 1986.[16] He married his third wife, Elizabeth Harper, a British citizen, on August 21, 2005. The two met while Harper was working as an assistant for the Chicago-based American Monetary Institute, which brought her to Kucinich’s House of Representatives office for a meeting.[17]

Kucinich was raised with four brothers, Larry, Frank, Gary and Perry; and two sisters, Theresa and Beth Ann. On December 19, 2007, Perry Kucinich, the youngest brother, was found dead in his apartment.[18][19][20] On November 11, 2008, his youngest sister, Beth Ann Kucinich, also died.[21]

In 2011, he sued a Capitol Hill cafeteria for damages after a 2008 incident in which he claimed to have suffered a severe injury when he bit into a sandwich and broke a tooth on an olive pit. The tooth broke and became infected. Complications led to three surgeries for dental work. The law suit, which had claimed $150,000 in punitive damages, was settled with the defendant agreeing to pay for the representative’s costs.[22]

On January 16, 2013, Kucinich joined Fox News Channel as a regular contributor.[23]

Kucinich’s political career began early. After running unsuccessfully in 1967, Kucinich was elected to the Cleveland City Council in 1969 at the age of twenty-three.[12] In 1972, Kucinich ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives, losing narrowly to incumbent Republican William E. Minshall, Jr. After Minshall’s retirement in 1974 Kucinich sought the seat again, this time failing to get the Democratic nomination, which instead went to Ronald M. Mottl. Kucinich ran as an Independent candidate in the general election, placing third with about 30% of the vote. In 1975, Kucinich became clerk of the municipal court in Cleveland and served in that position for two years.[24]

Kucinich was elected Mayor of Cleveland in 1977 and served in that position until 1979.[25] At thirty-one years of age, he was the youngest mayor of a major city in the United States,[12] earning him the nickname “the boy mayor of Cleveland”.[26] Kucinich’s tenure as mayor is often regarded as one of the most tumultuous in Cleveland’s history.[26][27] After Kucinich refused to sell Muni Light, Cleveland’s publicly owned electric utility, the Cleveland mafia put out a hit on Kucinich. A hit man from Maryland planned to shoot him in the head during the Columbus Day Parade, but the plot fell apart when Kucinich was hospitalized and missed the event. When the city fell into default shortly thereafter, the mafia leaders called off the contract killer.[28]

Specifically, it was the Cleveland Trust Company that suddenly required all of the city’s debts be paid in full, which forced the city into default, after news of Kucinich’s refusal to sell the city utility. For years, these debts were routinely rolled over, pending future payment, until Kucinich’s announcement was made public. In 1998 the Cleveland City Council honored him for having had the “courage and foresight” to stand up to the banks, which saved the city an estimated $195 million between 1985 and 1995.[29]

After losing his re-election bid for Mayor to George Voinovich in 1979, Kucinich initially kept a low profile in Cleveland politics. He criticized a tax referendumproposed by Voinovich in 1980, which voters eventually approved. He also struggled to find employment and moved to Los Angeles, California, where he stayed with a friend, actress Shirley MacLaine.[30] During the next three years, Kucinich worked as a radio talk-show host, lecturer, and consultant.[14] It was a difficult period for Kucinich financially. Without a steady paycheck, Kucinich fell behind in his mortgage payments, nearly lost his house in Cleveland, and ended up borrowing money from friends, including MacLaine, to keep it.[30] On his 1982 income tax return, Kucinich reported an income of $38.[30] When discussing this period, Kucinich stated, “When I was growing up in Cleveland, my early experience conditioned me to hang in there and not to quit… It’s one thing to experience that as a child, but when you have to as an adult, it has a way to remind you how difficult things can be. You understand what people go through.”[30]

In 1982, Kucinich moved back to Cleveland and ran for Secretary of State; however, he lost the Democratic primary to Sherrod Brown.[30] In 1983, Kucinich won aspecial election to fill the seat of a Cleveland city councilman who had died.[31] His brother, Gary Kucinich, was also a councilman at the time.

In 1985, there was some speculation that Kucinich might run for mayor again. Instead, his brother Gary ran against (and lost to) the incumbent Voinovich. Kucinich, meanwhile, gave up his council position to run for Governor of Ohio as an independent against Richard Celeste, but later withdrew from the race.[31]After this, Kucinich, in his own words “on a quest for meaning,” lived quietly in New Mexico until 1994, when he won a seat in the Ohio State Senate.[31]

In 1996, Kucinich was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing the 10th district of Ohio. He defeated two-term Republican incumbent Martin Hoke by three percentage points. However, he has never faced another contest nearly that close, and has since been re-elected six times.[32]

Kucinich helped introduce and is one of 93 cosponsors (as of Feb. 22, 2010) in the House of Representatives of theUnited States National Health Care Act or HR 676 proposed by Rep. John Conyers in 2003,[33] which provides for a universal single-payer public health-insurance plan.

In 2008, Kucinich introduced articles of impeachment in the House of Representatives against President George W. Bush for the invasion and occupation of Iraq.[34]

Although his voting record is not always in line with that of the Democratic Party, on March 17, 2010, after being courted by President Barack Obama, his wife and others, he reluctantly agreed to vote with his colleagues for the Healthcare Bill without a public option component.[35]

Kucinich voted against the USA PATRIOT Act, against the Military Commissions Act of 2006,[36] and was one of six who voted against the Violent Radicalization and Homegrown Terrorism Act.[37] He also voted for authorizing and directing the Committee on the Judiciary to investigate whether sufficient grounds existed for the impeachment of Bill Clinton.[38]

Kucinich criticized the flag-burning amendment and voted against the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. His congressional voting record has leaned strongly toward a pro-life stance, although he noted that he has never supported a constitutional amendment prohibiting abortion altogether. In 2003, however, he began describing himself as pro-choiceand said he had shifted away from his earlier position on the issue.[39] Press releases have indicated that he is pro-choice and supports ending the abstinence-only policy of sex education and increasing the use of contraception to make abortion “less necessary” over time. His voting record since 2003 has reflected mixed ratings from abortion rights groups.[40]

He has criticized Diebold Election Systems (now Premier Election Solutions) for promoting voting machines that fail to leave a traceable paper trail.[41] He was one of the thirty-one who voted in the House to not count the electoral votes from Ohio in the United States presidential election, 2004.[42]

Kucinich has criticized the foreign policy of President Bush, including the 2003 invasion of Iraq and what he perceives as growing American hostility towards Iran. He has always voted against funding it. In 2005, he voted against the Iran Freedom and Support Act, calling it a “stepping stone to war”.[43] He also signed a letter of solidarity with Hugo Chávez in Venezuelain 2004.[44]

He advocates the abolition of all nuclear weapons, calling on the United States to be the leader in multilateral disarmament.[45] Kucinich has also strongly opposed space-based weapons and has sponsored legislation, HR 2977, banning the deployment and use of space-based weapons.[46]

Kucinich advocates US withdrawal from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) because, in his view, it causes the loss of more American jobs than it creates, and does not provide adequate protections for worker rights and safety and environmental safeguards. He is against the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) for the same reason.[47]

Kucinich is also in favor of increased dialog with Iran in order to avoid a militaristic confrontation at all costs. He expressed such sentiments at an American Iranian Council conference in New Brunswick, New Jersey which included Chuck Hagel,Javad Zarif, Nicholas Kristof, and Anders Liden to discuss Iranian-American relations, and potential ways to increase dialog in order to avoid conflict.[48]

He believes the US should move aggressively to reduce emissions that cause climate change because of global warming[49] and should ratify the Kyoto Protocol, a major international agreement signed by over 160 countries to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by each signatory.[50]

Kucinich and Ron Paul are the only two congressional representatives who voted[51] against the Rothman–Kirk Resolution,[52] which calls on the United Nations to charge Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad with violating the genocide convention of the United Nations Charter based on statements that he has made. Kucinich defended his vote by saying that Ahmadinejad’s statements could be translated to mean that he wants a regime change in Israel, not death to its people and supporters, and that the resolution is an attempt to beat “the war drum to build support for a US attack on Iran.”[53] In October 2009, Kucinich and Ron Paul were the only two congressional representatives to vote against H.Res.175 condemning the government of Iran for “state-sponsored persecution of its Bahá’í minority and its continued violation of the International Covenants on Human Rights.”

On January 9, 2009, Kucinich was one of the dissenters in a 390-5 vote with 22 abstentions for a resolution recognizing Israel‘s “right to defend itself [againstHamas rocket attacks]” and reaffirming the U.S.’s support for Israel. The other 4 “no” votes were Gwen Moore of Wisconsin, Maxine Waters of California, Nick Rahall of West Virginia, and Ron Paul of Texas.[54]

Kucinich is the only congressional representative to vote against[55] the symbolic “9/11 Commemoration” resolution.[56] In a press statement[57] he defended his vote by saying that the bill did not make reference to “the lies that took us into Iraq, the lies that keep us there, the lies that are being used to set the stage for war against Iran and the lies that have undermined our basic civil liberties here at home.”

In a visit to the rest of the Middle East in September 2007, Kucinich said he did not visit Iraq because “I feel the United States is engaging in an illegal occupation.”[58] Kucinich was criticized for his visit to Syria and praise of the President Bashar al-Assad on Syria’s national TV.[59] He praised Syria for taking in Iraqi refugees. “What most people are not aware of is that Syria has taken in more than 1.5 million Iraqi refugees,” Kucinich said. “The Syrian government has actually shown a lot of compassion in keeping its doors open, and being a host for so many refugees.”[60]

Despite Kucinich’s committed opposition to the war in Iraq, in the days after the September 11, 2001 attacks he did vote to authorize President Bush broad war making powers,[61] the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists. The Authorization was used by the Bush Administration in its justification for suspension of habeas corpus in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp and its wiretapping of American citizens under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Kucinich voted along with 419 of his House colleagues in favor of this resolution, while only one Congresswoman opposed, Representative Barbara Lee.

In March 2010, the House rejected a Kucinich resolution regarding the War in Afghanistan by a vote of 356–65.[62] The resolution would have required the Obama administration to withdraw all American troops from Afghanistan by the end of the year.[63][64] Kucinich reportedly based the resolution on the War Powers Resolution of 1973.[63]

In March 2011, Kucinich criticized the Obama administration’s decision to participate in the UN intervention in Libya without Congressional authorization. He also called it an “indisputable fact” that President Obama’s decision is an impeachable offense since he believes the U.S. Constitution “does not provide for the president to wage war any times he pleases,” although he has not yet introduced a resolution to impeach Obama.[65] In response, Libyan officials invited Kucinich to visit that country on a “peace mission”, but he declined, stating that he “could not negotiate on behalf of the administration.”[66]

Kucinich was criticized during his 2004 campaign for changing his stance on the issue of abortion.[39] His explanation was “I’ve always worked to make abortions less necessary, through sex education and birth control. But the direction that Congress has taken, increasingly, is to make it impossible for women to be able to have an abortion if they need to protect their health. So when I saw the direction taken, it finally came to the point where I understood that women will not be truly free unless they have the right to choose.”[67]

Ralph Nader praised Kucinich as “a genuine progressive”,[citation needed] and most Greens were friendly to Kucinich’s campaign, some going so far as to indicate that they would not have run against him had he won the Democratic nomination. However, Kucinich was unable to carry any states in the 2004 Democratic Primaries, and John Kerry eventually won the Democratic nomination at the Democratic National Convention.

On December 10, 2003, the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) announced the removal of its correspondents from the campaigns of Kucinich, Carol Moseley Braun and Al Sharpton.[68]

The announcement came one day after a Democratic presidential debate hosted by ABC News’ Ted Koppel, in which Koppel asked whether the candidacies of Kucinich, Moseley Braun and Sharpton were merely “vanity campaigns”, and Koppel and Kucinich exchanged uncomfortable dialog.[69]

Kucinich, previously critical of the limited coverage given his campaign, characterized ABC’s decision as an example of media companies’ power to shape campaigns by choosing which candidates to cover and questioned its timing, coming immediately after the debate.[68]

ABC News, while stating its commitment to give coverage to a wide range of candidates, argued that focusing more of its “finite resources” on those candidates most likely to win would best serve the public debate.[69]

In the 2004 Democratic presidential nomination race, national polls consistently showed Kucinich’s support in single digits, but rising, especially as Howard Deanlost some support among peace activists for refusing to commit to cutting the Pentagon budget. Though he was not viewed as a viable contender by most, there were differing polls on Kucinich’s popularity.

He placed second in MoveOn.org‘s primary, behind Dean. He also placed first in other polls, particularly Internet-based ones. This led many activists to believe that his showing in the primaries might be better than what Gallup polls had been saying. However, in the non-binding Washington, D.C. primary, Kucinich finished fourth (last out of candidates listed on the ballot), with only 8% of the vote. Support for Kucinich was most prevalent in the caucuses around the country.

In the Iowa caucuses, he finished fifth, receiving about 1% of the state delegates from Iowa; far below the 15% threshold for receiving national delegates. He performed similarly in the New Hampshire primary, placing sixth among the seven candidates with 1% of the vote. In the Mini-Tuesday primaries, he finished near the bottom in most states, with his best performance in New Mexico where he received less than 6% of the vote, and still no delegates. Kucinich’s best showing in any Democratic contest was in the February 24 Hawaii caucus, in which he won 31% of caucus participants, coming in second place to Senator John Kerry ofMassachusetts and winning Maui County, the only county won by Kucinich in either of his presidential campaigns. He also saw a double-digit showing in Maine on February 8, where he got 16% percent in that state’s caucus.

On Super Tuesday, March 2, Kucinich gained another strong showing with the Minnesota caucus, where 17% of the ballots went to him. In his home state of Ohio, he gained 9% in the primary.

Kucinich campaigned heavily in Oregon, spending 30 days there during the two months leading up to the state’s May 18 primary. He continued his campaign because “the future direction of the Democratic Party has not yet been determined”[70] and chose to focus on Oregon “because of its progressive tradition and its pioneering spirit.”[71] He won 16% of the vote.

Even after Kerry won enough delegates to secure the nomination, Kucinich continued to campaign until just before the convention, citing an effort to help shape the agenda of the Democratic Party. He was the last candidate to end his campaign. He endorsed Kerry on July 22, four days before the start of the Democratic National Convention.[72]

On December 11, 2006 in a speech delivered at Cleveland City Hall, Kucinich announced he would seek the nomination of the Democratic Party for President in 2008. His platform[73] for 2008 included:

Kucinich described his stance on the issues as mainstream.[74]

Kucinich told his supporters in Iowa that if he did not appear on the second ballot in any caucus that they should back Barack Obama:

“I hope Iowans will caucus for me as their first choice … because of my singular positions on the war, on health care and trade,” Kucinich said. “But in those caucus locations where my support doesn’t reach the necessary threshold, I strongly encourage all of my supporters to make Barack Obama their second choice.”[75][76]

At a debate of Democratic presidential candidates in Philadelphia on October 30, 2007, NBC‘s Tim Russert cited a passage from a book by Shirley MacLaine in which the author writes that Kucinich had seen a UFO from her home in Washington State. Russert asked if MacLaine’s assertion was true. Kucinich confirmed and emphasized that he merely meant he had seen an unidentified flying object, just as former US president Jimmy Carter has.[77] Russert then cited a statistic that 14% of Americans say they have witnessed a UFO.[77]

On November 16, 2007, Larry Flynt hosted a fundraiser for Kucinich at the Los Angeles-based Hustler–LFP headquarters, attended by Kucinich and his wife, which has drawn criticism from Flynt’s detractors. Attendees included such notables as Edward Norton, Woody Harrelson, Sean Penn, Robin Wright Penn, Melissa Etheridge, Tammy Etheridge, Stephen Stills, Kristen Stills, Frances Fisher, and Esai Morales. Campaign representatives declined to comment.[78][79]

In December 2007, author Gore Vidal endorsed Kucinich for president.[80]

Kucinich’s 2008 presidential campaign was advised by a steering committee including Progressive Democrats of America (PDA) Founder Steve Cobble, long-time Kucinich press secretary Andy Junewicz, former RFK, McCarthy, Humphrey, McGovern and Carter political consultant Michael Carmichael, former Carter Fundraiser Marcus Brandon, Ani DiFranco Tour Manager Susan Alzner, West Point Graduate and former Army Captain Mike Klein, former Communications Director of Democrats Abroad Sharon Manitta and New Jersey-based political consultant Vin Gopal. The campaign was seen as a platform to push progressive issues into the Democratic Party, including a not-for-profit health care system, same-sex marriage, increasing the minimum wage, opposing capital punishment, and impeachment.

On Monday, January 7, 2008 actor Viggo Mortensen endorsed Kucinich’s presidential campaign in New Hampshire.[81] On Thursday, January 10, 2008, Kucinich asked for a New Hampshire recount based on discrepancies between the machine-counted ballots and the hand-counted ballots. He stated that he wanted to make sure “100% of the voters had 100% of their votes counted.”[82]

On Tuesday, January 15, 2008, Kucinich was “disinvited” from a Democratic presidential debate on MSNBC. A ruling that the debate could not go ahead without Kucinich was overturned on appeal.[83] Kucinich later responded to the questions posed in the MSNBC debate in a show hosted by Democracy Now![84]

Kucinich dropped his bid for the Democratic nomination on Thursday, January 24, 2008, and did not endorse any other candidate. He later endorsed Barack Obama after he had won the nomination.[85][86] On Friday, January 25, 2008, he made a formal announcement of the end of his campaign for president and his focus on reelection to Congress.[87]

On August 27, 2008, he delivered a widely publicized speech at the Democratic National Convention.[88]

Until 2012, Kucinich had always been reelected to Congress by sound margins in his strongly Democratic-leaning districts, and had up until this election far won primary challenges against him for the Democratic nomination convincingly.

Kucinich defeated another Democratic primary challenger by a wide margin and defeated Republican Mike Dovilla in the general election with 66% of the vote.

His opponents included Cleveland City Councilman Joe Cimperman and North Olmsted Mayor Thomas O’Grady. In February 2008 Kucinich raised around $50,000 compared to Cimperman’s $228,000,[89] but through a YouTube money raising campaign he managed to raise $700,000, surpassing Cimperman’s $487,000.[90][91]

Cimperman, who was endorsed by the Mayor of Cleveland and The Plain Dealer, criticized Kucinich for focusing too much on campaigning for president and not on the district. Kucinich accused Cimperman of representing corporate and real estate interests. Cimperman described Kucinich as an absentee congressman who failed to pass any major legislative initiatives in his 12-year House career. In an interview, Cimperman said he was tired of Kucinich and Cleveland being joke fodder for late-night talk-show hosts, saying “It’s time for him to go home.”[92][93] An ad paid for by Cimperman’s campaign stated that Kucinich has missed over 300 votes, but by checking the ad’s source, the actual number was 139.[94] However, Kucinich is well known for his constituency service.[95]

A report suggested that representatives of Nancy Pelosi and American Israel Public Affairs Committee would “guarantee” Kucinich’s re-election if he dropped his bid to impeach Dick Cheney and George W. Bush, though Kucinich denies the meeting happened.[96][97] It was also suggested that Kucinich’s calls for universal health care and an immediate withdrawal from Iraq made him a thorn in the side of the Democrats’ congressional leadership, as well as his refusal to pledge to support the eventual presidential nominee, which he later reconsidered.[92]

Kucinich took part in a debate with the other primary challengers. Barbara Ferris criticized him for not bringing as much money back to the district as other area legislators and authoring just one bill that passed during his 12 years in Congress. Kucinich responded “It was a Republican Congress and there weren’t many Democrats passing meaningful legislation during a Republican Congress.”[98]

Kucinich won the primary, receiving 68,156 votes out of 135,589 cast to beat Cimperman 52% to 33%.[99]

Kucinich defeated former State Representative Jim Trakas in the November 4, 2008 general election with 153,357 votes, 56.8% of those cast.

Kucinich defeated Republican nominee Peter J. Corrigan and Libertarian nominee Jeff Goggins in the November 2, 2010 general election with 101,343 votes, 53.1% of those cast.[100]

Redistricting threw Kucinich into the same district as another Democratic incumbent, Marcy Kaptur. The two competed in the Democratic primary on March 6, 2012, but Kucinich lost after an increasingly bitter campaign. Kucinich had been endorsed by another House member, Barney Frank of Massachusetts.[101]

Kucinich was mentioned frequently as a possible 2012 candidate for congress in the state of Washington, and openly admitted exploring the idea, but ultimately decided against running and decided to retire from congress when his term ended in January 2013.[102][103][104]

Based on his voting record in Congress, the American Conservative Union (ACU) gave Kucinich a conservative rating of 9.73%,[105] and for 2008, the liberalAmericans for Democratic Action (ADA) gave him a liberal rating of 95%.[106]

In the aftermath of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, Kucinich called for the Federal Reserve System to be put under control of U.S. Treasury.[107] Additionally, banks shall no longer be allowed to create money, putting an end to fractional-reserve banking.[108] He cites Stephen Zarlenga as the initiator of that proposal.

On January 8, 2007 Kucinich unveiled his comprehensive exit plan to bring the troops home and stabilize Iraq. His plan included the following steps:[109]