CLE Myths: The “A” In Cleaveland

The link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

Just where did the Cuyahoga River reach Lake Erie when people like Moses Cleaveland arrived?

by Peter Krouse, Cleveland.com, December 27, 2023

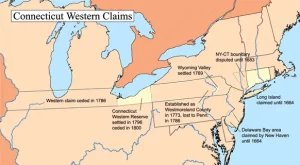

“When Cleveland Belonged to Connecticut”

from New England Historical Society

The City of Cleveland and nearly all of Northeastern Ohio once belonged to Connecticut. The land, 3.5 million acres of it, was called the Western Reserve.

The Story of Cleveland’s 1st Neighborhood (video)

In this episode of the History and the Stories of our Neighborhoods, we will tell the story of Cleveland’s first neighborhood, which is the Flats and the Warehouse District – some of the most popular neighborhoods in which to visit when in town. The rich history of the city, starts here, and as we celebrate Cleveland’s 225th birthday of it’s founding, this is a great way to tell the story of such a prominent place in the city’s history.

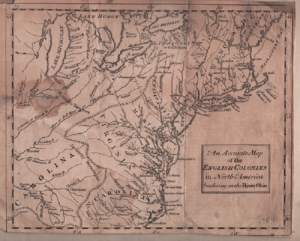

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175by Dr. John Grabowski, PhD | WRHS Krieger Mueller Historian

On July 4th 1796, on the bank of what is now Conneaut Creek, a group of surveyors led by Moses Cleaveland celebrated Independence Day. Naming the site Port Independence, they fired off a salute, ate a meal of pork and beans, and drank to six patriotic toasts. Eighteen days later they arrived at the mouth of Cuyahoga River, climbing up a hill on the east bank (near what is now St. Clair Avenue) to the heights over the river valley.

The river marked the boundary of that part of the Western Reserve to which Native Americans had ceded their claims in the Greenville Treaty of 1795, and it seemed a likely area to begin the exploration and mapping out of the lands now “available” to settlement. Yet it took several weeks for Moses Cleaveland to decide if the site would serve as the center for the survey party’s work, and what some might call the capital of the Western Reserve. He made that decision in August. It was the best possible choice and considered naming the settlement Cuyahoga, but his colleagues convinced him that it should take his name.

This is a quick and far too easy summary of the founding of Cleveland for it misses the broader impact of the event. When Cleaveland’s surveying crew began to lay out the lines that would define the townships of the Western Reserve, they were imposing a change on the landscape that exceeded anything that had come before.

The hanging of John O’mic in 1812 according to the Plain Dealer-1917

High Spots in #Cleveland History. Hanging of John O’Mic on Public Square. Found @Cleveland_PL Clipping File (1917).

Ohio’s Most Historic Battlefields Cleveland.com 1/31/2017

The link is here