CLE Myths: The “A” In Cleaveland

The link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

{gallery}western_reserve_era/cleaveland{/gallery}

Just where did the Cuyahoga River reach Lake Erie when people like Moses Cleaveland arrived?

by Peter Krouse, Cleveland.com, December 27, 2023

“When Cleveland Belonged to Connecticut”

from New England Historical Society

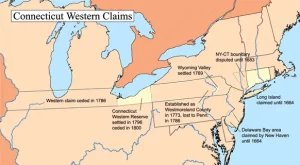

The City of Cleveland and nearly all of Northeastern Ohio once belonged to Connecticut. The land, 3.5 million acres of it, was called the Western Reserve.

The Story of Cleveland’s 1st Neighborhood (video)

In this episode of the History and the Stories of our Neighborhoods, we will tell the story of Cleveland’s first neighborhood, which is the Flats and the Warehouse District – some of the most popular neighborhoods in which to visit when in town. The rich history of the city, starts here, and as we celebrate Cleveland’s 225th birthday of it’s founding, this is a great way to tell the story of such a prominent place in the city’s history.

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175by Dr. John Grabowski, PhD | WRHS Krieger Mueller Historian

On July 4th 1796, on the bank of what is now Conneaut Creek, a group of surveyors led by Moses Cleaveland celebrated Independence Day. Naming the site Port Independence, they fired off a salute, ate a meal of pork and beans, and drank to six patriotic toasts. Eighteen days later they arrived at the mouth of Cuyahoga River, climbing up a hill on the east bank (near what is now St. Clair Avenue) to the heights over the river valley.

The river marked the boundary of that part of the Western Reserve to which Native Americans had ceded their claims in the Greenville Treaty of 1795, and it seemed a likely area to begin the exploration and mapping out of the lands now “available” to settlement. Yet it took several weeks for Moses Cleaveland to decide if the site would serve as the center for the survey party’s work, and what some might call the capital of the Western Reserve. He made that decision in August. It was the best possible choice and considered naming the settlement Cuyahoga, but his colleagues convinced him that it should take his name.

This is a quick and far too easy summary of the founding of Cleveland for it misses the broader impact of the event. When Cleaveland’s surveying crew began to lay out the lines that would define the townships of the Western Reserve, they were imposing a change on the landscape that exceeded anything that had come before.

CLEAVELAND, MOSES (29 Jan. 1754-16 Nov. 1806), founder of the city of Cleveland, was born in Canterbury, Conn. In 1777, Cleaveland began service in the Revolutionary War in a Connecticut Continental Regiment, and graduated from Yale. Resigning his commission in 1781, he practiced law in Canterbury, and on 2 Mar. 1794 married Esther Champion and had four children. As one of 36 founders of the CONNECTICUT LAND CO. (investing $32,600), and one of 7 directors, in 1796 Cleaveland was sent to survey and map the company’s holdings.

When the party arrived at Buffalo Creek, N.Y., Cleaveland met in treaty with Red Jacket, Joseph Brant, Farmer’s Brother, and other Iroquois chiefs, and with gifts and persuasion convinced them their land had already been ceded through Gen. Anthony Wayne’s Treaty of Greenville. Although they had not signed the treaty, the Indians relinquished their claim to the land to the CUYAHOGA RIVER. At the mouth of Conneaut Creek, the party on 27 June 1796 negotiated with the MASSASAGOES tribe, who challenged their claim to their country. Cleaveland described his agreement with the Six Nations, promised not to disturb their people, and gave them trinkets, wampum, and whiskey in exchange for safety to explore to the Cuyahoga River. Cleaveland arrived at the mouth of the Cuyahoga on 22 July 1796, and believing that the location, where river, lake, low banks, dense forests, and high bluffs provided both protection and shipping access, was the ideal location for the “capital city” of the Connecticut WESTERN RESERVE, paced out a 10-acre New England-like Public Square. His surveyors plotted a town, naming it Cleaveland. In Oct. 1796, Cleaveland and most of his party returned to Connecticut, where he continued his law practice until his death, never returning to the Western Reserve. A memorial near his grave in Canterbury, Conn., erected 16 Nov. 1906 by the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, reads that Cleaveland was “a lawyer, a soldier, a legislator and a leader of men.”

Plain Dealer article that ran on July 9, 1995 and written by Bob Rich.

MOSES FINDS THE PROMISED LAND

Plain Dealer, The (Cleveland, OH) – Sunday, July 9, 1995

Author: BOB RICH

July 5th, 1796, after a merry (and liquid) Fourth of July the night before, Moses Cleaveland and his 50-man surveying crew from the Connecticut Land Co. set out from Conneaut to find the mouth of the Cuyahoga River, where they would lay out a new capital for their Promised Land.

Cleaveland was a burly, powerful-looking man with a swarthy complexion that may have fooled Indians into thinking he was one of them. He was a Yale graduate with experience in the Revolutionary War and had practiced law for 30 years in his hometown of Canterbury, Conn.

He was appointed general of militia by the state. Cleaveland was the logical man to head the survey of the company’s newly acquired 3 million acres east of the Cuyahoga River; plus, his own money was at stake.

Real estate speculation was the way to get rich (or get swindled) in those early days of the American republic. The Connecticut investors had paid 40 cents an acre for their Western Reserve holdings, and the chances of getting rich looked very good. New England was filled with landless, unemployed men who would be able to lay down a little cash for their own lot.

And so Cleaveland’s surveying party of axmen, chainmen, rodmen and compassmen hacked its way through a trackless forest, laying out 5-mile square townships, sometimes eating boiled rattlesnake and berries when hunters came back empty-handed. With a broiling sun, mosquitoes, swamps and rainstorms, most of the party suffered from dysentery, cramps and fevers – and they had 55 miles to go from the Pennsylvania border to the Cuyahoga.

Somewhere along the line, Moses Cleaveland and some of his men got into a boat and coasted along Lake Erie until July 22, 1796, when they headed into the mouth of the sand-choked Cuyahoga – “crooked river,” in the Iroquois language.

Now they met the real enemy: swarms of malarial mosquitoes that rose to attack the sweaty bargemen. Above the eastern bank of the river, the heights were covered with chestnut, oak, walnut and maple trees, but down in the valley, they could smell the swamps and the decay; because the river had so many sandbars, a large sailing vessel would never make it from the lake into the river.

But no matter – the sandbars could be dredged. Here was a river from the interior of Ohio feeding into a freshwater lake, a river that would carry product out and finished goods in. This was the place to establish the capital of New Connecticut.

So the Cleaveland party landed at the foot of today’s St. Clair Ave., climbed up the hill and set to work surveying town lots. The men took 10 acres in the center of the plateau to establish a New England village-style Public Square; pushed a north-south street that they called Ontario through the center, and an even wider path from east-to-west called Superior.

After three months of surveying, Cleaveland took his crew back home to Connecticut.

Cleaveland never came back, but his surveying crew had complimented him by naming the settlement after him. Years later he said, “While I was in New Connecticut I laid out a town on the bank of Lake Erie, which was called by my name, and I believe the child is now born who may live to see that place as large as Old Windham.” Since Old Windham’s population was 2,200, eventually, he was proved right.

Only three people from the Cleaveland party chose to stay: Job Stiles, his wife, Tabitha, and Joseph Landon, and they shared a log cabin put up by the surveyors on what is now W. 6th St. and Superior. Their only company was a little group of Seneca Indians nearby. To the east and south was unbroken wilderness filled with wild game – turkey, bear, deer and timber wolves; west was the river and millions of trees; north was drinking-water pure Lake Erie.

Landon got one blast of winter winds whistling off the lake, and Cleaveland’s population dropped by one-third.

It got right back up there when Edward Paine arrived and began to trade with the Chippewa and Ottawa Indians. He would pull up stakes several years later and found Painesville.

That winter, the Indians befriended their white neighbors in the cabin on the hill, supplying them with game. Eventually, they would lose their ancestral lands to these same neighbors for a little money and a lot of whiskey.

Whoever nastily nicknamed Cleveland “The Mistake on the Lake” must have been there that first year when a few pioneers straggled in in the spring, in time to catch the ague (malaria) with chills and fever. When they recovered, they left for higher ground 6 miles southeast in what became Newburg, or east to Doan’s Corners (now E. 105th and Euclid).

By 1800, the total population was one family. You wouldn’t have wanted to bet on Cleveland’s survival much less its growth to the size of Old Windham, Conn. – unless, that is, you knew that one family in that one cabin belonged to Lorenzo Carter.

From the Ohio Historical Society

The link is here

Moses Cleaveland was the founder of Cleveland, Ohio.

Following the American Revolution, Americans began to migrate westward in large numbers. There were lengthy disputes about the ownership of this land. The federal government encouraged the states to give up their claims within the Northwest Territory. Connecticut was one of the states with land claims in Ohio. While giving up its rights to most of the land, the state maintained its ownership of the northeastern corner of the territory. This area became known as the Connecticut Western Reserve. The Connecticut Land Company was a group of private speculators who purchased approximately three million acres of the Western Reserve.

In 1796, the company sent one of its major investors, General Moses Cleaveland, to Ohio. He led the survey of company lands within the Western Reserve. Cleaveland had served under General George Washington for several years during the American Revolution and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Connecticut militia. In 1781, Cleaveland had opened a law practice in Canterbury, Connecticut. He also had served as a member of the Connecticut state convention that ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

Cleaveland’s surveying party of fifty-two people included two women. The surveyors laid out a town along the eastern bank of the Cuyahoga River and named it Cleaveland. Because of a spelling error on the original map, the town of Cleaveland was spelled as Cleveland. The surveying party experienced many difficulties and hardships. It did not complete as much work as had originally been expected and returned to Connecticut in the fall. Another surveying team went back to the Western Reserve the next spring but Moses Cleaveland was not a part of it.

Cleaveland never returned to Ohio. He spent the rest of his life with his legal practice and business interests in Connecticut. He died in 1806.