Bankrolling Higher Learning Philanthropists’ Feud Led to Founding of Two Schools

Plain Dealer article written by Bob Rich and published on February 4, 1996

BANKROLLING HIGHER LEARNING PHILANTHROPISTS’ FEUD LED TO FOUNDING

OF TWO SCHOOLS

On a bitter, cold February day in 1851, a brightly polished new locomotive pulled into Cleveland packed with passengers from Columbus and Cincinnati to celebrate the completion of the city’s first railroad, the Cleveland-Columbus-Cincinnati Co.

Among the officials who greeted the out-of-towners on the courthouse steps were the mayor, William Case, and the superintendent of the railroad, Amasa Stone, who not only had stock in the line, but a salary of $4,000 a year to run it.

These two were to clash in later years, and their mutual dislike and competitiveness would strongly affect higher education in Cleveland.

The famous and accomplished Case family: father, Leonard, and sons, Leonard Jr., and William, were unquestionably the first big names in 19th century Cleveland education, starting with the Cleveland Medical College in 1843. They also made several tries to create a Cleveland university, but came up short in the money department each time.

When Leonard Case Jr. died in 1880, he accomplished by his bequest of $1 million in land and money what he couldn’t manage while alive: a successful new school of higher education – the Case School of Applied Science, on Rockwell Ave. It was the first independent school of technology west of the Alleghenies.

The Cases were doing their business friends a favor because industry had become complicated; special skills were needed, and the idea was that sons of middle-class families could afford to give up working for wages while they studied for better jobs. As for the sons and daughters of Cleveland’s elite, they would continue to be taught liberal arts at tiny Western Reserve University in Hudson, Ohio.

But that school was practically broke, and so the trustees were perhaps more than willing to be lured away to University Circle in Cleveland by that man whose personality was as flinty as his name – Amasa Stone.

Stone’s arrogance had made him unpopular even in his own top-drawer society circle. But it also drove him as a philanthropist to do things for which only he would get the credit – and that included competing with the Cases by bankrolling a successful university in Cleveland.

Stone had made a phenomenal climb to wealth and power since those early railroad days. From banking to contracting, from a rolling mill to screw manufacturing, even to a trotting track in Glenville, Amasa Stone was in the thick of it. He gave the Home for the Aged Protestant Gentlewomen to the YWCA, saw his two daughters married extremely well – Clara to John Hay, a famous diplomat, writer and secretary to Abraham Lincoln; and Flora to industrialist Samuel Mather.

But tragedy dogged him: his son, Adelbert, was drowned in a swimming accident at Yale. He lost his reputation when a train on one of his own lines plunged into the Ashtabula gorge during a snowstorm in December 1876, killing 92 passengers and injuring more. The main arch of the bridge had caved in – a wooden bridge, designed, patented, and built by Stone himself, against the advice of his own engineer who wanted a new stone or iron bridge to span the gorge.

His physical and psychological health was already bad by 1880, when his business empire began to collapse; only philanthropy relieved some of the pressure.

Stone offered the little Hudson college $500,000 if it would move to what is now the University Circle area. There were conditions: he wanted the school named for himself, (but had to settle for Adelbert College of Western Reserve University); wanted to design and construct the buildings; Cleveland citizens had to provide the land for the site; and the site had to be built next to the new Case School, which had bought some farmland east of Euclid Ave. and E. 107th St.

Leonard Case Jr. may have been dead, but Amasa Stone was still competing with the family name. The little Hudson school lunged at the offer. As a local writer put it, according to historian William G. Rose, they “hitched their educational wagon to the new star of progress and threw old-fashioned prudence to the wind.”

A depressed Amasa Stone commited suicide in 1883, but his youngest daughter Flora and her husband, Samuel Mather, would help more than 30 religious, charitable and educational institutions in their time, including establishing the women’s undergraduate school at Western Reserve.

And Florence and sister Clara were able to honor their autocratic father with the Amasa Stone Chapel.

There was one thing he wanted that he didn’t get: a demand that the two schools exist side-by-side “in close proximity and harmony.” The two institutions promptly built a fence between them.

Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times

Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times

Brief history of Ralph J. Perk written by Dr. Richard Klein, Cleveland State University

Race, Violence, and Urban Territoriality – Cleveland’s Little Italy and the 1966 Hough Uprising

Written by Todd M. Michney for the Journal of Urban History, March 2006 (http://academic.csuohio.edu/tebeaum/courses/local/michney.pdf)

A racially motivated shooting during the 1966 Hough uprising in Cleveland, Ohio, provides an effective lens to scrutinize the complicated legacy of racialized violence with which the Little Italy neighborhood, where the shooting took place, had become associated. White residents’ localized racial anxieties stemmed from a trend toward increased interracial contact in public spaces and particularly the public schools—which in turn linked to population movements in the nearby vicinity and metropolitan area as a whole. Little Italy’s resi- dents historically marked their territory and sought to ward off racial residential transition through the use of violence, but ultimately their success depended on location, the neighborhood’s unique geography, and an easing of the city’s housing shortage for African Americans by the 1970s. Little Italy today is a gentrifying cultural hub with few (if any) black residents; meanwhile, attempts are being made to moderate its reputation for racial intolerance.

“Train Dreams” by Pete Beaty from Belt Magazine

“Train Dreams” by Pete Beaty from Belt Magazine. The story of the Van Sweringen brothers.

“The Secret History of Chief Wahoo” by Brad Ricca from Belt Magazine 2014

“The Secret History of Chief Wahoo” by Brad Ricca from Belt Magazine 2014

Highways in Cleveland

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

HIGHWAYS. Roads in Cleveland and other cities have served 2 main purposes. First, roads were built for commerce, including traffic movement and economic growth. Next, roads helped create and separate neighborhoods, allowing development of specialized districts for housing and business and an increase in property values. Inevitably, proponents of roads for traffic purposes came into conflict with those favoring the community and property interests of those living alongside. Officials in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County enjoyed only modest success in accommodating these conflicting goals. After 1900 state and federal officials financed part of the construction costs, leading to an upward shift in the level of conflict but no better luck in resolving it. The net result during the period between 1796-1990 was the creation of a vast and improved road network that never appeared affordable and adequate for traffic flow and local development. In 1796 MOSES CLEAVELAND† and his survey party reached the site of the city and began marking off streets for future settlement. The grid idea with a couple of radial routes prevailed. Cleaveland’s group sketched PUBLIC SQUARE, with Ontario running north to south and Superior east to west marking the center. Four additional streets bounded the outskirts of the area. In 1797 a second group of surveyors added 3 additional streets to the town plan. Actually, none of these streets existed; the marking of roads was simply a component in the division of land into lots for expeditious sale, the primary interest of the CONNECTICUT LAND CO. The net result of the 2 plattings, however, was to create a frame for Cleveland’s development that emphasized expansion toward the east and south. From 1810-15, only Superior and Water streets were open for travel, but tree stumps and bushes remained as obstacles. Ontario was open south of the square but was equally undeveloped.

During the 1820s, growth of a warehouse and wholesale district in the FLATS along the CUYAHOGA RIVER encouraged officials to develop adjacent roads. On the far north, Bath St. ran between the river and Water St. Farther south, 4 lanes allowed traffic to descend into the Flats from Water and Superior streets. Construction in 1824 of 2 bridges across the river linked commercial and residential development around Public Square with river traffic and the smaller west side. Approval and completion of a route, it appears, rested on a petition presented by property owners, along with the perception among officials that property values and trade would be enhanced. Streets constructed after 1820 often were named for leading businessmen and politicians who fostered commerce. Case St. honored LEONARD CASE†, a prominent real-estate developer. In 1836 the council dedicated Clark St. for Jas. S. Clark, who had constructed the Columbus Bridge with a view toward development of his property in the Flats.

After 1840 leaders in urban America undertook the task of improving their streets. In 1880 Geo. Waring, an engineer active in street and sanitary improvements, conducted a survey of street conditions in the nation’s cities. Half of the streets remained unpaved; only 2.5% of the paved roads were constructed of asphalt, a smooth, dust-free surface. During the 1870s, officials in cities such as New York, Cleveland, Chicago, and Washington, DC, had installed wooden blocks, which muffled the noise of horses and carts. But wooden streets, soaked in creosote oil as a preservative, fueled the fires that occasionally destroyed portions of major cities. Other surfaces included cobblestone and granite blocks, set on beds of sand, and gravel, the cheapest type of surface. Because abutters rather than the city usually financed improvements, the emphasis was on rapid extension of streets to houses and buildings in outlying districts rather than on securing the best surface. Many hoped that street improvements would encourage a quick increase in property values, perhaps leading to the creation of exclusive residential districts, such as Chicago’s Union Park and EUCLID AVE.. in Cleveland.

The desire for miles of cheap roadway guided street designers in Cleveland. By the early 1880s, a lengthy network of streets, bridges, and viaducts had been constructed. The city had increased in size to 26.3 sq. mi., and the number of streets had jumped to 1,155, running 444 mi. in length. The CENTRAL VIADUCT was under construction to connect the city at Ohio St. with outlying areas south and west. The quality of surfaces varied; approx. 92 mi. had been graded, and another 32 mi. graded and curbed. During the 1840s, city officials had paved Superior St., and by the 1880s paving, though still costly, had been applied to 58 mi. Altogether, 41% of the city’s streets were improved. However popular these improvements, neither the costs nor the construction materials proved satisfactory. During the mid-1880s, officials installed block stone over several streets, including Broadway, Woodland, Superior, and Erie, a length of 13 mi., at a cost of $723,000. But the block stone was in fact the third type of improvement attempted; earlier pavements, including asphalt, had become “unendurable” and had generated a “long controversy.” Nor was controversy limited to this particular project. During the early 1870s, property owners had petitioned the council to open 17 streets, including Payne and Sheriff. Approval rested on the legal requirement that petitioners would repay bonds issued by the city through tax assessments amounting to more than $1 million. Once the improvements were in place, however, several of the beneficiaries secured a court order preventing the city from collecting the taxes.

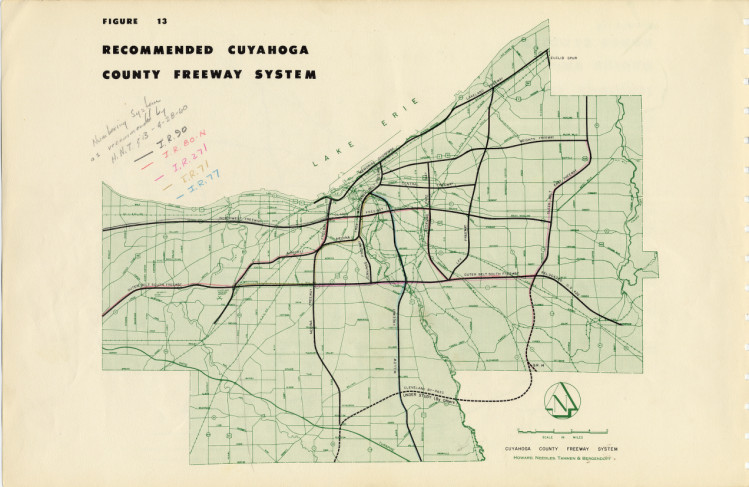

Around 1900, rapid increases in auto sales began to highlight older problems and create new ones for those charged with road building. Competition between trolley operators and motorists for limited space added a fresh dimension to the traditional question of whether roads should benefit traffic flow or property values. Unable to satisfy diverse constituencies, road officials accelerated the pace of improvements and extensions. Between 1900-40, officials at every level paved more than 1.2 million mi. Local authorities proved unable to finance such costly improvements, forcing the level of highway funding (and decision making) up to the state and federal levels. In fact, the “battle for the streets” in cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland prompted federal officials to contemplate funding the construction of a national expressway system. During the 1920s, road engineers and political leaders in the Cleveland region undertook major programs of extending and widening streets and roads. Federal and state funds were available for a number of these projects, which helped reduce the burden on local ratepayers and permitted more construction. Four-lane highways, replacing narrower and often twisting roads built prior to heavy traffic, were a popular design around Cleveland and many cities. On the far east, Kinsman, Euclid, and Lee roads were among those upgraded; and on the west, the 4-lane projects included West Lake Rd. Widening of older streets inside Cleveland proved slower and more costly, but engineers widened and resurfaced a large number, especially where trolleys and automobiles competed for space on narrow brick pavements. Projects such as the widening and extension of Chester from E. 13th to WADE PARK had to take place in sections of 8 to 10 blocks a year. In 1928 engineers counted nearly 1,800 mi. of roadway in the region constructed with federal, state, and county funds. Even more, they planned redevelopment and construction totaling 281 mi. in Cuyahoga County and another 312 mi. in the outlying areas at a cost of $63 million, exclusive of rights-of-way and damages.

Widening and extending roads failed to solve the traffic mess. In 1934, the low point of the Great Depression, county engineers surveyed traffic volume on major streets. During a 12-hour period, they counted 43,000 vehicles crossing the Superior Bridge. The outward movement of households and businesses added traffic along newer roads. Engineers counted 13,000 vehicles on Cedar Ave. west of Fairmount; 1,500 crossed Cedar at Warrensville, roughly the edge of suburban settlement. Leaders in politics and highway engineering added to the problem by spreading funds across numerous projects, partially satisfying demand and yet constructing roads that were below the standard of heavier and faster traffic. By the 1930s engineers had begun to define the problems of constructing a highway system in political rather than technical terms. Road building always required the support of politicians, and the difference after the 1920s is one of emphasis. In brief, engineers lacked the financial resources and legal remedies required to construct a road network adequate to traffic. Demand for road improvements routinely outstripped resources. Not until additional funds were made available and direction of road building centralized, many argued, could engineers improve the road network. Even during harsh Depression days, moreover, automobile registrations jumped 16%, and travel increased 45%. Truckers and motorists contended with traffic jams; downtown businessmen faced declining sales; and all endured the waste and tragedy of accidents. “Our street systems,” reported the Regional Assn. of Cleveland in 1941, “belong to the horse-and-buggy era.”

By the early 1940s, the construction of limited-access roads, popularly known as expressways, appeared to offer a solution to traffic jams and political stalemate. In 1939 the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads offered formal articulation of a plan for constructing a national expressway system. Within a year or two, road engineers and city planners formed committees to fix local routes and secure the support prerequisite to a lobbying campaign with state and federal governments. In Nov. 1944, members of the committee in Cleveland published a plan for expressway construction consisting of an inner and outer beltway plus 7 radial routes. Expressways would eventually serve 20% of the region’s traffic, or so ran the reasoning, drawing enough traffic from local roads to eliminate “need for many extensions and widenings.” Fewer autos on local streets, in this scheme, would “ensure quiet in the neighborhood,” encouraging residents not to seek “`greener pastures’ in the suburbs.” Proponents of expressways in Cleveland, as elsewhere, also promised a reduction in the number of accidents and, of course, “quick movement of heavy traffic.” Estimates of costs ran to $228 million during the course of 10 to 20 years, with the state and federal governments paying most of the bill.

The national expressway system was a popular idea. In 1944 members of Congress and Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt approved construction of the Interstate Highway System but failed to vote funds for construction costs. Despite the widespread celebration of such limited-access roads as the Pennsylvania Turnpike (opened 1940), leaders in the highway field, including truckers, economists, and the directors of farm and automotive groups, always sought to shift the financial burden of highway construction from themselves to general revenues, to taxes on other groups of road users, and to property owners. In cities such as Cleveland, debate revolved around the potential of expressways for serving urban renewal, resuscitating the downtown and speeding up traffic. Not until 1956 could members of Congress and Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower approve dedication of the gasoline tax to rapid development of the federal highway systems, particularly the Natl. System of Interstate & Defense Highways. During the mid-1950s, engineers in Cleveland spent $14 million to construct a section of the Innerbelt running 6/10 of a mile. In the future, federal officials would pay 90% of those costs, leaving the state responsible only for 10%. Free expressways proved no panacea in Cleveland. The scale of the interstate system, with its multiple lanes and wide interchanges, heightened the differences between those favoring traffic flow and others committed to property development. Conflict in the political arena began during the process of identifying routes. A route proposal submitted by a group of consulting engineers rested “solely on the basis of traffic,” the planning director of Cleveland advised the county engineer on 1 June 1954, and “would result in so great a disruption of over-all community plan that we cannot endorse it.” Route coordinates remained imprecise for several years pending the availability of funds. By Dec. 1957, however, the report of another consulting firm had it that “the primary purpose of a freeway is to serve traffic. . . .”

Between 1958 and the mid-1970s, planning and construction of the interstate system emerged as tangible facts on the landscape. Generally, those favoring traffic service predominated. The new Innerbelt, according to a report of 7 Oct. 1961 in the Cleveland PLAIN DEALER, “Loosens Downtown Traffic.” Occasionally, proponents of local development and property values managed to secure changes in routings and the elimination of extensions. In mid-1965, officials of the State Highway Dept. agreed to major changes in the location of interstate routes through the eastern suburbs. Observers noted that residents of these communities possessed wealth, which was imagined to translate directly into political protection, but unity and savvy were far more significant in the counsels of government. Traditional programs of road building and remodeling continued during the period of constructing the interstate system. The out-migration of households and businesses and a doubling of traffic during the first decade after World War II guided highway planners. From 1946 through the late 1950s, engineering staffs emphasized removal of bricks and streetcar tracks and repaving with concrete and asphalt. Beginning in 1946, officials spent $80,000 a mile to remodel Cedar Ave. between E. 2nd St. and E. 109th. The interstate system never refocused traffic toward downtown, nor did it encourage residents to remain in the city. By the late 1960s, officials had to extend main roads far to the south, west, and east in order to serve traffic and property in numerous subdivisions around the region. During the 1970s, attention in the region and nation shifted to repair and rehabilitation. Cleveland exhausted its funds, and other levels of government had to contend with inflation, declining resources, and fierce competition for road improvements.

From the early 19th century through the late 1970s, engineers, politicians, and developers in the Cleveland region directed the funding and construction of a large and up-to-date highway system. Materials and design approximated national standards in each period. Equally, road builders in the Cleveland region served the conflicting interests of highway users and adjoining owners of property. During the period up to ca. 1900, property enjoyed the greatest attention; thereafter, the crush of traffic forced greater attention to the design and siting of roads with a view toward vehicular service. After 1900, moreover, the momentum of highway building encouraged the training of professionals in the fields of road construction and land-use planning. Professional status conferred political and social legitimacy, allowing planners and engineers to interpret traffic and urban changes for politicians and residents. Engineers in the Cleveland region and nationwide held a larger influence and exercised a greater authority, especially because they had access to the revenues created by state and federal taxes on the sale of gasoline. Nonetheless, rarely could engineers in the Cleveland region–or in the nation as a whole–fund and construct the mileage demanded. During this entire period, road builders served the conflicting needs of a commercial civilization.

Mark H. Rose

Florida Atlantic Univ.

Urban Transportation in Cleveland

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

URBAN TRANSPORTATION. During the last 150 years, transit in Greater Cleveland has gone from the horse and buggy to modern, diesel-powered buses and electric-rail coaches. Ownership has gone from small, privately owned, and minimally regulated systems (prior to 1910), to private corporations with tight public controls (1910-41), to city programs governed by a small board (1942-75); and to an autonomous regional authority (1975 to the present). Cleveland’s urban transit programs have run the gamut of problems and opportunities faced by all metropolitan systems, whose histories often have been complex and stormy.

The first urban transportation system established in the Cleveland area was the CLEVELAND & NEWBURGH RAILWAY, incorporated in 1834 by prominent Clevelanders. Operated by Silas Merchant, this line ran from a quarry atop Cedar Glen via Euclid to PUBLIC SQUARE, with passenger service commencing at the Railway Hotel at what is now E. 101st St. and Euclid. The line went bankrupt in 1840 and received close to a $50,000 as a subsidy from the county, but continued losing money and ceased operations in 1842. Ca. 1857, omnibuses, or “urban stagecoaches,” appeared on Cleveland’s streets. At first they ran between the downtown hotels and the railroad stations, saving patrons the trouble of carrying bags through “rutted, quagmire streets,” but they later extended service to “residential sections, remote business locales, and parks and water cures.” But omnibus travel, while more convenient than walking, was itself uncomfortable and unreliable. Horse-drawn carriages had difficulty on muddy streets, and omnibuses often did not operate in such conditions. Cleveland omnibus operator Henry S. Stevens sought a solution to this early urban transit problem and found it in the horse-drawn streetcar: rails secured in the streets made it easier for the horses to pull the cars in all sorts of weather. The first “oat-powered railway” in Ohio was introduced in Cincinnati in 1859; that year CLEVELAND CITY COUNCIL granted 2 of Stevens’s companies–the EAST CLEVELAND RAILWAY CO. and the Woodland Ave. Street Railroad Co. (later the Kinsman St. Railroad Co.)–franchises to lay rails in the streets. Service began regularly on 5 Sept. 1860; between 1863-76, 8 other companies were formed to operate lines along other streets.

To extend service from the end of these lines into the countryside, 3 suburban steam lines were organized in the late 1860s and 1870s. The CLEVELAND & NEWBURGH “DUMMY” RAILROAD, organized in 1868, ran from the Woodland-E. 55th St. barns to Broadway and Miles Ave.; its steam locomotives were disguised as passenger cars to fool horses, thus earning it the name “dummy” railroad. It operated until numerous accidents forced it into receivership in 1877. The Rocky River Railroad, organized in 1867, began at W. 58th and Bridge and ran to a resort called Cliff House; this line, instrumental in the development of LAKEWOOD, operated until 1882. The third such line was JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER†’s Lakeview & Collamer Railroad Co., in operation from 1875-81. In the 1870s, complaints about streetcar service were frequent. The uncoordinated transportation system required riders to take several different lines to reach their destinations and to pay a new fare on each. In 1879 TOM L. JOHNSON†, a veteran street railway businessman new to Cleveland, sparked the beginning of a prolonged struggle that would affect not only intracity transportation but local politics as well. He fought to enter the Cleveland street railway business, then worked to develop a single-fare ride from the west side into downtown. The CLEVELAND RAILWAY FIGHT OF 1879-83 pitted Johnson against banking, coal, iron, and shipping tycoon MARCUS ALONZO HANNA† and had profound implications for the future of local transportation.

Between 1879-93, the Cleveland transportation system was electrified and consolidated. As early as 1872, when the EPIZOOTIC epidemic struck area horses and brought most street railways to a halt (a few lines used mules, which were unaffected by the epidemic), street railway owners had sought other forms of motive power. The first local attempt to use electricity to power the cars came in July 1884, but proved unsatisfactory. Electrical power was used successfully by the East Cleveland St. Railway Co. on 18 Dec. 1888; it began running 4 electrical cars the next day and extended its electric service to Public Square on its Euclid line in July 1889. The first electric car to reach the Square, however, had been on the South Side Railroad’s Jennings Ave. (W. 14th) line on 19 May 1889. By 1894 all but 2 lines in Cleveland had been electrified; these were the Payne Ave. and Superior St. lines of FRANK ROBISON†’s Cleveland City Cable Railway Co. Cars on these lines were powered by cable ropes pulled through concrete tubes by large flywheels located in powerhouses. The city’s first cable car appeared on 17 Dec. 1890 on the Superior Line; the change from horse-drawn cars to cable cars was gradual, but Robison had adopted cable cars after they had become outmoded by electricity. The Superior line was electrified in July 1900, the Payne line in Jan. 1901–the latter carried the last cable car in Cleveland on 19 Dec. 1901.

Prior to 1893, Cleveland had 8 different companies operating 22 different lines. Consolidation of these scattered lines began in the 1880s. In 1885 the Kinsman St. Railroad Co. (operating the Woodland and Kinsman lines) merged with Hanna’s West Side Railway Co. (Detroit, Lorain, and Franklin-W. Madison lines) to form the WOODLAND AVE. AND WEST SIDE RAILWAY CO.. In 1889 Frank Robison’s Cleveland City Cable Railway Co. was formed by the mergers of the St. Clair St. Railroad Co. with the Superior Railroad Co. (Payne and Superior lines). In Mar. 1893 the CLEVELAND ELECTRIC RAILWAY CO. was formed by the merger of Azariah Everett’s EAST CLEVELAND RAILWAY CO. (Euclid, Cedar, Wade Park, Garden [Central], Quincy, and Mayfield lines) with Joseph Stanley’s BROADWAY & NEWBURGH STREET RAILROAD CO. (Broadway and Belt lines); in April the Cleveland Electric Railway added Tom and Al Johnson’s Brooklyn St. Railroad Co. (Pearl, Scovill, and Abbey Lines) and their South Side St. Railroad Co. (Jennings [W. 14th], Scranton and Clark, and Fairfield lines). The Cleveland Electric became known as the Big Consolidated, and shortly after its mergers were completed, the Little Consolidated–more properly the Cleveland City Railway Co.–took shape in May when Robison’s Cleveland City Cable Co. merged with Hanna’s Woodland Ave. & West Side Street Railroad.

Cleveland Electric suffered through a violent strike in 1899 (see STREETCAR STRIKE OF 1899), but for the most part it did battle with the Little Con until acquiring it in July 1903. For the rest of the decade, Cleveland Electric fought with reform mayor Tom L. Johnson, who argued for a 3-cent fare andMUNICIPAL OWNERSHIP of the lines, using the battle to educate the people about the evils of “privilege” and the benefits of public ownership. The railway disputes eventually were brought before the U.S. District Court, Northern Ohio, where the determined efforts of Judge ROBERT WALKER TAYLER†, a superb conciliator and mediator, resolved the issue. His “Cost of Living Service,” released on 15 Mar. 1909, was based on the premise that “the community never pays more than the cost of service rendered; that the owners of the property never, by any device, get more than 6% on the agreed amount of their investment; and that the community will at all times know just how the property is being operated and have the power to correct any abuse either of management or of service.” This was the basis of the Tayler Franchise adopted by Cleveland City Council in Dec. 1909 and approved by the voters in Feb. 1910. When the franchise became operational 1 March 1910, it inaugurated a new era in Cleveland’s transportation history. Franchises of the former competing companies were given to the CLEVELAND RAILWAY CO.; appraised value was $14,675,000. Guidelines for costs and changes were prescribed. The innovative agreement provided for the position of city street railroad commissioner (appointed and removed only by the mayor but paid by the company), for boards of arbitration, and for municipal ownership, when such was permitted under Ohio’s constitution. Cleveland’s public/private system caught the attention of the nation. Mayor NEWTON D. BAKER† appointed PETER WITT† as railroad commissioner, who scrutinized every move of the company. Witt also pioneered the “skip-stop” plan, under which inbound cars stopped at every other street and outbound ones at the other. Because each patron walked 1 additional block per day, service was faster. He also developed and patented the “Pete Witt Car,” which had front and rear doors for entrance and exit.

The system that brought Cleveland some of the best and cheapest service in the nation was not immune to the Depression of the 1930s. Decreased patronage, inability to meet fixed charges, including the 6% return, and continued use of aging equipment spurred interest in public ownership. An Analytical Survey of the Cleveland Railway Co., completed in July 1937, carried overtones of the inevitability of public transit ownership, which finally arrived in 1942. Twenty years after the Ohio constitution had permitted a city to purchase a transit system, Cleveland’s city council passed an ordinance for the purchase, transit bonds amounting to $17.5 million were issued, and at midnight 23 April 1942 Cleveland took possession of the system. Operation and management became part of the Department of Public Utilities under Commissioner Walter J. McCarter until 3 Nov. 1942 when voters approved a charter amendment establishing an independent transit board “to supervise, manage and control the transportation system.” The 3-member board, appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the city council, began to function on 1 Jan. 1943; its first chairman was William C. Reed. McCarter continued as the system’s first general manager. Although the amended city charter completely separated the administration of transportation from other public utilities, the city council retained the right to approve new capital expenditures, the acquisition of other transit systems or franchise extensions, and the disposal transit system property. With these exceptions, the CTS board followed the model of the directors of a private corporation–to determine policies and to give the general manager responsibility for operations.

The city’s performance with public transit was successful until the late 1960s. During World War II ridership had increased rapidly as automobile manufacturing ceased, gasoline was rationed, and employees, including many more women, worked more days per week. With a prosperous CTS, the 1942 debt, scheduled for repayment in 20 years, was redeemed in half the time. A 1951 Reconstruction Finance Corp. loan of $29.5 million was granted by the federal government for the purchase of vehicles for improvements in surface facilities, and for assistance with the construction of a rapid rail system. In exchange for the loan, the RFC insisted that the transit system be free of all oversight by Cleveland City Council and that the number of transit board members be increased to 5. The city council retained its right to approve board appointees, to dispose of the system as a whole, and to issue CTS bonds. Operation of the rapid transit between Windermere and Public Square began on 15 March 1955; service to the west side to W. 117 St. began on 14 August 1955 and was extended to the airport in 1968, making Cleveland the first city in the Western Hemisphere to have rapid-rail transit from the center city to the airport. While the east-west rapid transit marked another milestone in the city’s transportation history, buses, first used extensively in the 1920s, proved more flexible if less glamorous than rail-bound streetcars, which were gradually phased out–the last one ran on 24 Jan. 1954. CTS was a “profit-making” venture between 1942-67, but it lost $483,474 in 1968, $1,774,861 in 1970. Charged with operating from the farebox, Cleveland could no longer hold fares to $.50 for local rides without additional sources of income, but the city was reluctant to give up control of the failing system to a regional authority despite its increasing deficits. In Dec. 1974 the GREATER CLEVELAND REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY was created to rescue CTS and to consolidate the other local transit companies operating in the area. Cuyahoga County voters overwhelmingly approved a 1% sales tax in July 1975 to subsidize RTA’s operations and a new, lower fare structure became effective in September.

The mix of RTA’s revenue sources changed dramatically because much of the new system’s income now came from public sources instead of the farebox. By 1985 total revenues were $135.4 million, with passenger fares bringing in only $36.8 million; the sales tax contributed $77.9 million, the state chipped in $6.8 million, and Federal Operational Assistance provided $11.3 million. In addition, significant monies for new rolling stock, system upgrade, and route expansion were received from the federal government on a matching basis.

The regional authority was not the panacea hoped for in 1975. Although ridership increased from 78 million in 1974 to 130 million in 1980, it began to decline again, this time to 59.97 million in 1993, reflecting the continuing exodus of the city’s population and businesses. Diminishing passenger traffic, reductions in federal subsidies, and reduction in anticipated revenues from sales taxes forced RTA to raise fares and cut service. In 1982 the local fare was raised to $.85 and it continued to escalate, reaching $1.25 for local rides in 1993. Hoping to increase ridership, RTA built a walkway from its TOWER CITY CENTER station to the new Gateway sports center to provide efficient transit service for fans attending CLEVELAND INDIANS andCLEVELAND CAVALIERS games.

Dallas Young (dec.)

Christiansen, Harry. Northern Ohio’s Interurbans and Rapid Transit Railways (1965).

——. Trolley Trails through Greater Cleveland and Northern Ohio (1975).

Morse, Kenneth S. P. Cleveland Streetcars (1955).

Bridges in Cleveland

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

BRIDGES. Cleveland, split firmly though unequally by the CUYAHOGA RIVER, is deeply dependent on bridges. The city’s east and west sides are joined today by both high fixed spans and lower-level opening bridges. Trains cannot climb steep grades, and their frequency of crossing is low enough to permit the use of opening spans of various sorts. Auto and truck traffic, however, is of such high density that delays occasioned by spans opening for river traffic would be intolerable. Autos and trucks are capable of climbing the relatively steep approaches to high-level bridges over the Cuyahoga River, and today the bridges carrying heavy traffic loads (the Innerbelt Bridge, the HOPE MEMORIAL BRIDGE, the VETERANS MEMORIAL BRIDGE, and theMAIN AVE. BRIDGE) are high fixed spans. There are more than 330 bridges in the immediate Cleveland area, including both the Cuyahoga River bridges and those spanning other features of the area’s mixed terrain and industrial complexes.

When Cleveland was first platted, just before 1800, the east and west sides were joined by ferries, which were soon supplanted by the first Center St. Bridge. The Center St. Bridge was based on a system of chained floating logs, a section of which would be pulled aside to permit the passage of vessels. A later version of this bridge was based on pontoon boats, and ultimately on a succession of fixed structures. The first substantial bridge over the Cuyahoga appears to have been the first COLUMBUS STREET BRIDGE, erected ca. 1836, with a draw section permitting vessels to pass. The roofed bridge was 200′ long and 33′ wide, including sidewalks. In 1836, following the incorporation of both Cleveland and OHIO CITY (CITY OF OHIO), Cleveland ordered the destruction of its portion of the Center St. Bridge, which had the effect of directing commerce across the Columbus St. span, thereby bypassing Ohio City. Enraged Ohio City residents damaged the Columbus St. span and hostilities began. West-siders ultimately gained their point, retaining a Center St. bridge along with the Columbus St. span. With Cleveland’s annexation of Ohio City in 1854, traffic increases led to construction of the Main St. Bridge and the Seneca (W. 3rd) St. Bridge, and a rebuilding of the Center St. Bridge. In 1870 the Columbus bridge was replaced by an iron truss structure, which in turn was replaced by a 3rd bridge in 1895. The Seneca span collapsed in 1857 and was replaced first by a timber draw span, and in 1888 by a Scherzer roller-lift bridge–the first of its kind in Cleveland. The Center St. Bridge had a similar history, its wooden structure being replaced several times, finally with the unequal swinging span of iron built in 1900, which remained in service in 1993 as the sole swinging bridge in the city.

By 1993, 4 great vehicular bridges provided high-level spans over the Cuyahoga Valley. They were the Veterans Memorial Bridge (opened in 1918), the Hope Memorial Bridge (1932), the Main Ave. Bridge (1939), and the Innerbelt Bridge (1959). Near the present Veterans Memorial Bridge may be seen the remains of one of Cleveland’s great historical bridge achievements, the SUPERIOR VIADUCT, opened with great fanfare in Dec. 1878. Its great west side stone approaches were joined with a swinging metal span crossing the Cuyahoga toward PUBLIC SQUARE and downtown Cleveland. The viaduct served until Veterans Memorial was opened in 1918, as a result of complaints about delays in vehicular traffic from the frequent openings that river traffic required. Originally known as the Detroit-Superior Bridge, Veterans Memorial was a 2-level structure, with streetcars utilizing the lower deck until their demise in the 1950s. When inaugurated, it was the world’s largest double-deck reinforced-concrete bridge.

Planned as early as 1916 but delayed by World War I, Hope Memorial was opened as the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge in 1932. The bridge has a lower deck originally designed for rapid-transit trains and trucks, but never used. Four colossal pylons, with figures symbolizing transportation progress, were preserved as the bridge underwent a thorough renovation in the 1980s, at which time it was renamed the Hope Memorial Bridge to honor the stonemason father of former Cleveland entertainer Bob Hope. Planned as early as 1930 to replace the low-level Main Ave. Bridge, with its attendant traffic delays, the Main Ave. High-Level Bridge was opened in 1939, after a remarkably fast construction largely financed with PWA funds. The bridge is 2,250′ long; with approaches, it is more than a mile in length. Eight truss-cantilever spans of varying lengths constitute the bridge itself, with added bridgework at the eastern end joining the bridge to the lakefront freeway. Having undergone significant emergency repairs in the 1980s, the Main Ave. Bridge was closed from 1990-92 for a major rebuilding and renovation of the deck structure, sidewalks, and railings.

The old CENTRAL VIADUCT, opened in 1888, stood approximately at the location of the Innerbelt Bridge (1959). The entire span consisted of 2 bridges of iron and steel placed on masonry piers. Originally the river was spanned with a swing section, which was replaced with an overhead truss in 1912. Closed in 1941, the Central Viaduct was finally replaced in 1959 by the Innerbelt Bridge, built with substantial funding resulting from the Federal Highway Act of 1956. The bridge is Ohio’s widest, and nearly a mile long, with the central portion consisting of a series of cantilever-deck trusses with a reinforced-concrete deck and asphaltic concrete driving surface. It serves to connect I-71 and I-90 West with the Innerbelt Freeway. Two other bridges built as part of the interstate highway system are the I-490 bridge, which replaced the Clark Ave. Bridge, and the I-480 bridge spanning the Cuyahoga through VALLEY VIEW. A substantial high-level rail bridge, the CLEVELAND UNION TERMINAL Railway Bridge, just south of the Veterans Memorial Bridge, carries 2 rail tracks and 2 tracks used by commuter rapid trains of the GREATER CLEVELAND REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY.

Nearly a dozen movable bridges remained across the Cuyahoga serving both vehicular traffic and railroads in 1993. Among the vehicular bridges are the old Center St. Swing Bridge, the Willow St. Lift Bridge (over the Old Cuyahoga Channel between the west side and WHISKEY ISLAND), the Columbus St. Lift Bridge, the Carter Rd. Bridge, and the W. 3rd St. Bridge. The remaining lift bridges serve various railroads; some were actively used, such as the ConRail Lift Bridge near the mouth of the Cuyahoga–the first bridge up the Cuyahoga from Cleveland Harbor–but many remained in lifted positions in the 1980s in response to industrial declines in the Cuyahoga Valley and consequent declines in railroad traffic. The rail bridges included Scherzer roller-lift bridges, bascule structures, and jacknife bridges, in addition to lift bridges such as the ConRail structure.

In addition to those spanning the Cuyahoga River, there are other bridges in Cleveland worthy of note. Architect CHAS. F. SCHWEINFURTH†, noted for his design of the downtown TRINITY CATHEDRAL, designed 4 unusually fine bridges that span Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. (formerly Liberty Blvd.) inROCKEFELLER PARK. Structurally interesting in their combining of steel, concrete, and decorative stone, they include 3 vehicle bridges (Wade Park, Superior, and St. Clair avenues) and a railroad bridge (built for the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway). Other noteworthy structures include the Forest Hills pedestrian bridge in nearby CLEVELAND HEIGHTS, the concrete-arch Monticello Bridge carrying Monticello Blvd. over Euclid Creek, the 1910 DETROIT-ROCKY RIVER BRIDGE (demolished 1980), the Hilliard Rd. Bridge over the Rocky River (1926), and the steel arched Lorain Rd. Bridge crossing Metropolitan Park near the Rocky River.

Although a large number of engineers, designers, and architects, organizations, and consortia can be identified with recent bridge history in Cleveland, several individuals and organizations stand out. One of these is Chas. Schweinfurth, whose designs were referred to earlier. Another prominent designer and builder associated mainly with midwestern railroad bridges was AMASA STONE†, who, unfortunately, is often remembered for the tragic 1876 collapse of his innovative wrought-iron Howe truss bridge that spanned the Ashtabula River, supporting the tracks of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, of which he was president. Cleveland firms that have had prominent roles in the history of Cleveland bridges are Wilbur J. Watson & Associates–known for the 1940 Columbus St. Bridge and later for pioneering concrete bridge structures–and Frank Osborn’s OSBORN ENGINEERING CO., which began building local bridges at about the end of the 19th century. Another firm with historical prominence was the KING IRON BRIDGE & MANUFACTURING CO., which had important roles in the building of the Veterans Memorial Bridge, the old Central Viaduct, and the present (1993) Center St. Bridge. In the post-World War II period, the firm of Howard, Needles, Tammen & Bergendoff was heavily involved with bridges in Cleveland, as attention shifted away from building new bridges to rebuilding and rehabilitating existing structures.

Willis Sibley

Bluestone, Daniel M., ed. Cleveland: An Inventory of Historic Engineering and Industrial Sites (1978).

Bridges of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County (1918).

Watson, Sara Ruth and John R. Wolfs. Bridges of Metropolitan Cleveland (1981).

Aviation in Cleveland

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

AVIATION. In the 1920s Cleveland emerged as a center for the early development of commercial mail and passenger flight operations, and since that time has become a focal point for the advancement of modern aviation and aerospace technology.

Cleveland’s initial contact with aviation began during World War I when the federal government provided incentive for its development by introducing the delivery of mail by air. Just as Cleveland benefited from its position on the New York-to-Chicago railroad corridor, its size and strategic location fit ideally into a coast-to-coast route for airmail delivery from New York City to San Francisco. In 1918 federal officials began constructing a transcontinental system of navigational beacons or “guide lights” to initiate coast-to-coast airmail delivery, and Cleveland, aided by enthusiastic support from the Chamber of Commerce and local business groups, was chosen as one of the principal stops. The first regular airmail service as far as Chicago was inaugurated in mid-December of that year when planes piloted by U.S. Army flyers arrived in Cleveland, landing on a grassy strip in Woodland Hills Park near E. 93rd St. and Kinsman Ave. Planes on these runs carried 850 lbs. of mail (letters cost $.06 to send) and the flights experienced few major difficulties. The first truly transcontinental airmail trips in the nation began 8 Sept. 1920, with planes making their Cleveland stop at Martin Field, located behind the aircraft plant (seeGLENN L. MARTIN CO.) on St. Clair Ave. The U.S. government considered these makeshift fields unsatisfactory, and in 1925, CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT emerged when a team of city officials and Army Air Service personnel selected 1,040 acres at Brookpark and Riverside Dr. as the site for a new municipal airport. The much larger facility reflected good long-term planning, although the administration and passenger buildings did not open until 4 years later.

The timing of this $1.25 million airport expenditure was ideal because in 1925 Congress passed the Kelly Act, under which the federal government turned over operation of its airmail routes to private parties through competitive bidding. Civil aviation was born, and Cleveland benefited from the entrepreneurial spirit of the early airplane owners. Not only did private contract flyers carry mail to various cities, mostly in the Midwest, but these fledgling businesses began to seek passengers as well. Ford Commercial Air lines inaugurated daily trips between Cleveland and Detroit on 1 July 1925, and soon Natl. Air Transport, a future component of United Airlines, launched what would become the first continuous service. Four thousand planes cleared the new field in 1925; in 1926 the total reached 11,000; and a year later, volume had grown to 14,000. Travelers bound for Detroit in 1929 made the 100-minute flight from Cleveland in a Ford tri-motor metal monoplane paying a fare of $18 one way and $35 round-trip. Airline personnel continually reassured wary passengers that air travel was safe, pointing out that planes, pilots, and mechanics were licensed by the Aeronautics Branch of the Dept. of Commerce and a rigid daily inspection of equipment was made. Aircraft landing was indeed made much safer after 1930 when Cleveland’s municipal airport installed the world’s first radio traffic system. General airport upgrading in the mid-1930s also made for better flying, and pilots favored the Cleveland field because of its relatively obstruction-free approaches.

With the introduction of the improved Douglas DC-3 airplane in the late 1930s, the number of trips canceled by adverse conditions lessened significantly, making it possible for an airline to turn a profit on a flight without hauling mail. By World War II, 3 airlines, American, Pennsylvania Central, and United, dominated Cleveland’s commercial traffic. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the greater dependability and faster speeds of the planes, the lower fares, and the decline in intercity railroad passenger service expanded the market for air travel. Both passenger traffic and mail increased, as did the number of flights for airlines such as Eastern, TWA, United, and Trans-Canada, which connected Cleveland travelers to the major cities of the U.S. and Canada and to international flights around the world.

The most notable technological advance during the period was the advent of the jet engine and the rapid disappearance of piston-driven craft. Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8 jets began to land at Cleveland Hopkins Intl. Airport, and in the late 1970s, the next generation of wide-bodied Boeing 747s and DC-10s regularly deposited passengers here. Only a few turbo-prop jets reminded passengers of the early jet age, and these craft belonged almost exclusively to small feeder lines such as the locally based WRIGHT AIRLINES, INC.. Massive improvements of Hopkins facilities were begun in 1973 involving a $60 million terminal-expansion plan which included rehabilitation of the west concourse and the longer runways needed to accommodate the jet age and the increase in passengers that it brought.

While physical improvements at Greater Cleveland’s 3 airports were readily apparent, the traveler, after 1978, also recognized that airlines themselves were changing as the revolutionary process of deregulation by the federal government swept the industry in the late 1970s. Competition increased and so did mergers as fares were lowered to attract more passengers. In order to maintain profitability, trunk carriers reduced the number of flights or ended service outright in what was rapidly becoming an intense rivalry. In spite of the volatility, however, a number of new airlines entered the field, and in 1992 Continental and USAir were major carriers operating out of Cleveland’s municipal airport.

Greater Cleveland had satellite airports as well. To relieve congestion, especially traffic generated by private aircraft, Cleveland’s downtown field, BURKE LAKEFRONT AIRPORT, opened in 1947 to provide ready access to the central business for travelers using their own or company planes or the regularly scheduled community flights. The other major landing strip at CUYAHOGA COUNTY AIRPORT on Richmond Rd. also served general aviation. Located in Richmond Hts., this field initially opened in the spring of 1929 when Ohio Air Terminals, Inc. acquired a 272-acre parcel for a flying school and related activities; however, it closed a year later after legal action was taken against the promoters because of airplane noise and danger. A pro-aviation climate after World War II prompted small-plane enthusiasts to win voter approval for the issuance of county general obligation bonds to rehabilitate the field. Although nearby property owners tried to block the plan, the Cuyahoga County Airport opened on 30 May 1950.

Cleveland aviation involved transporting freight as well as mail and people. In Feb. 1936, the Railway Express Agency’s Air Div. started air-rail express service through an interchange agreement with Pan American Airways that linked Cleveland with cities on 20 American airlines and most of Latin America. From the mid-1930s on, the forwarding of express and freight increased steadily. After World War II, air cargo service frequently became part of the individual carrier’s Cleveland operation. American Airlines, for instance, inaugurated such service between Hopkins and 42 other cities on its far-flung system in Sept. 1946. More recently, freight-only air forwarders have served the community, including Federal Express and the Flying Tiger Line.

In addition to the development of commercial aviation, Cleveland played an early role in the research and production of aircraft, beginning in 1918. That year inventor-entrepreneur Glenn L. Martin came to Cleveland and established a factory at 16800 St. Clair Ave. where he and his talented colleagues built the Martin MB bomber–acknowledged by military authorities to be superior in its class. The Martin-designed bomber, scheduled for quantity production when World War I ended, was produced here for the U.S. Army and Navy, for the Post Office, and for commercial use. Although Martin moved his plant to Baltimore in 1929, the GREAT LAKES AIRCRAFT CO. operated a portion of the former Martin facility until that company disbanded in the mid-1930s. Aircraft parts continued to be made here, however, by firms such as Cleveland Pneumatic Aerol Co. and Thompson Products (TRW). Cleveland returned to aircraft production during World War II, when the Cleveland Bomber Plant owned by the Dept. of Defense and operated by General Motors (GM) made the B-29 bomber adjacent to the municipal airport.

Aviation research and development was also furthered by the NATIONAL AIR RACES, which were held here intermittently throughout the 1930s and from 1946-49. In 1929 the quality of Cleveland’s airport and the organizational skills of the Chamber of Commerce, together with support from Glenn Martin and Thompson Products, made possible the first aircraft races and the satellite aeronautical exposition. Although the races popularized aviation and were a source of civic pride, they were also important in advancing aircraft technology. Contests such as the Bendix trophy race from Los Angeles to Cleveland and the Thompson Trophy Race–a 55-mi. closed course marked by pylons–were proving grounds to test the airplanes’ durability and performance under extreme conditions. Cleveland’s stature as a research center was affirmed when the Natl. Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) established an aircraft engine laboratory in 1940. During World War II, its investigations included the problems associated with B-29 engines which were being assembled here by GM. Renamed the Lewis Flight Propulsion Research Laboratory after the war, the NACA facility conducted research to improve jet engine technology. In 1958 the Lewis Research Center became part of the Natl. Air & Space Admin. (NASA) and became actively engaged in the Mercury and Apollo space programs.

Although aircraft production did not remain in Cleveland, the city retained a meaningful presence in the manufacture of airplane parts and the advancement of jet engine and aerospace research and development.

H. Roger Grant

Univ. of Akron

Dawson, Virginia P. Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratories and American Propulsion Technologies (1991).

Hull, Robert. September Champions–The Story of America’s Air Racing Pioneers (1979).

Fordon, Leslie N. “On to Cleveland Race–1929,” in American Aviation Historical Journal, Spring (1966).

Wings Over Cleveland (1948).

Giblin, Ann M. “Aviation Enterprise, Technology and Law on Richmond Rd: The Curtiss Wright Hanger and the Cuyahoga County Airport,” in Journal of the Cuyahoga County Archives, (1983).

Morton, Jan. “Cleveland’s Municipal Airport,” in National Municipal Review (1926).

Aviation Library, WRHS.