Trump to save coal, nuclear plants that are unable to compete (6/1/2018) Plain Dealer

Developers update Cleveland City Council on lakefront plans (5/30/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

K&D strikes deal to buy 55 Public Square office tower, with mixed-use renovation plans (5/30/2018) Plain Dealer

Cleveland police recruitment plan says more women, minority officers needed to reflect city’s diversity (5/29/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga Community College trustees approved a nearly 10 percent tuition increase Thursday (5/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Bedrock’s May Co. building redo getting ready to roll (5/23/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Younger Ohioans Urged To Register And Vote, But Stats Show Historically, They Don’t (5/22/2018) Ideastream

FirstEnergy must guarantee nuclear clean up, environmental groups tell feds (5/22/2018) Plain Dealer

Have opioid deaths in Northeast Ohio finally crested? Evidence suggests yes (5/21/2018) Cleveland.com

Shoreline Erosion: Changes threaten Lake Erie coast (5/19/2018) Sandusky Register

Lake Erie rescue project is boosted by construction of West Side tunnel (5/18/2018) Plain Dealer

Teacher pay varies widely across region (5/17/2018) Dayton Daily News

Scientists Say Lake Erie Toxic Algae Blooms Could Be Part of Climate Change Loop (5/16/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio Board of Education to Consider Delaying Overall Grades for School Districts (5/13/2108)

New plan shows how CWRU can grow within boundaries and be greener, more welcoming (5/13/2018) Plain Dealer

Here are the 9 most interesting storylines from this week’s Ohio primary election (5/11/2018) Cleveland.com

Mike DeWine wins Republican primary in Ohio governor’s race (5/9/2018) Clefveland.com

Cordray wins the Ohio Democratic governor’s primary (5/9/2018) Cleveland.com

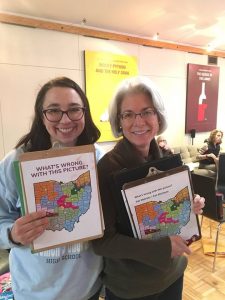

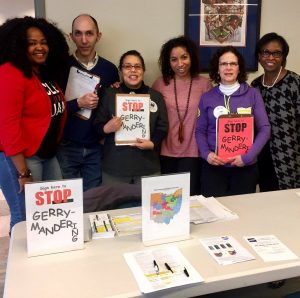

Ohio votes to reform congressional redistricting; Issue 1 could end gerrymandering (5/9/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio primary: Voters pick candidates for one of the year’s biggest governor races (5/8/2018) Washington Post

Report Finds Big Gaps in Regional Employer Needs, Employee Skills (5/8/2018) Cleveland Scene

Federal forecasters said Monday that this summer’s Lake Erie algal bloom could reach the size of last summer’s bloom–the 3rd-largest on record (5/7/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio’s School Districts Struggle to Cover Lost Transportation Funding (5/7/2018) Cleveland Scene

The Browns Are Already Talking About a New Stadium or Major Renovations (5/3/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio Issue 1 Q&A: congressional redistricting and the ills of gerrymandering – Election preview (5/3/2018) Cleveland.com

Algal blooms harder to control because of climate change, other factors, data shows (5/1/2018) Toledo Blade

Closing FirstEnergy’s reactors will not destabilize grid, says PJM, but launches probe into future fuel security (4/30/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio has ‘long way to go’ to solve Lake Erie’s algae problem, state officials say (4/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Ford’s Move to End Most U.S. Car Production Will Force Ohio Parts-Makers to Adjust (4/28/2017) WOSU

Communities across the state need to take more action to keep Lake Erie clean, Ohio EPA says (4/27/2018) News5

FirstEnergy Solutions definitely to close its nuclear power plants (4/25/2018) Plain Dealer

Issue 1 Could Remake How Ohio Draws Congressional Districts (4/23/2018) Ideastream)

Cleveland, Akron media shakeups bring job cuts (4/22/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Why Cleveland Hopkins airport has more passengers, lower fares despite fewer destinations (4/22/2018) Cleveland.com

Worried, sick and weary, Puerto Rican families settle in Cleveland (4/20/2018) Cleveland.com

Greater Cleveland RTA ridership drops 9.5 percent to record low in 2017 (4/19/2018) Cleveland.com

Campaign for Ohio congressional redistricting reform is low-profile and low-budget (4/18/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio legislators look to clamp down harder on communities that try to pass local gun restrictions (4/17/2019) Cleveland.com

Should school districts get an A-F grade? State report card overhaul debated (4/17/2018) Plain Dealer

Has the Cleveland Plan for school improvement stalled? Maybe not, but test scores have (4/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Medicaid expansion has helped, but poverty persists in Ohio (4/13/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Ohio and Cleveland gain little on “Nation’s Report Card,” as national scores stay flat (4/10/2018) Plain Dealer

As the opioid epidemic rages, the fight against addiction moves to an Ohio courtroom (4/8/2018) Washington Post

FirstEnergy’s efforts to re-make itself into a delivery-only electric utility — has many people worried that power plants will shut down and Ohio will run short of electricity (4/8/2018) Plain Dealer

Ground broken for The Lumen at Playhouse Square, billed as largest downtown residential project in 40 years (4/5/2018) Plain Dealer

A Cleveland Landfill Will Host Ohio’s Largest Solar Farm (4/5/2018) WOSU

Ohio exports to China in crosshairs of looming trade war (4/4/2018) Columbus Dipatch

Ohio State’s shrinking share of low-income students (4/3/2018) The Lantern

Students in gun-control movement turn from marches to elections (4/2/2018) Columbus Dispatch

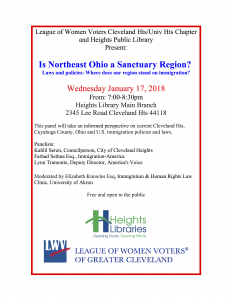

Among counties, Cuyahoga near top in Midwest for attracting immigrants (4/2/2018) Cleveland.com

Congolese part of new tapestry of immigration to Cleveland (4/1/2018) Plain Dealer

In Cleveland’s Superior Arts District, development activity stokes optimism – and some fears (4/1/2018) Plain Dealer

Report documents Ohio’s job slide, presses candidates for solutions (3/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Cleveland’s 2018 budget includes millions of dollars dedicated to police reform (3/29/2018) Cleveland.com

FirstEnergy Solutions asks DOE to help save its old power plants (3/29/2018) Plain Dealer

FirstEnergy Solutions will close its nuclear power plants (3/28/2018) Plain Dealer

State’s new education plan gets warm reception from Cuyahogs County residents (3/28/2018) Plain Dealer

Stuck in dial-up age, rural Ohio still pushing for high-speed internet (3/25/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Students lead thousands in March for Our Lives rally on Public Square (3/24/2018) Cleveland.com

FirstEnergy Solutions bankruptcy restructuring likely, power plants would be closed or sold (3/23/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio says for the first time it’s declaring western Lake Erie impaired by the toxic algae that has fouled drinking water in recent years (3/22/2018) Associated Press

Ohio Senate backs change in teacher evaluations over Cleveland objections (3/22/2018) Plain Dealer

Spending bill before Congress would keep $300 million for Great Lakes programs (3/22/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga County Council lacks confidence in administrators, council president says (3/20/2018) Cleveland.com

Playhouse Square to lift curtain on 34-story apartment tower (3/19/2018) Plain Dealer

Cleveland schools’ plan shifts focus to K-8 (3/18/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Ohioans Divided Over Education Consolidation Bill (3/15/2018) Cleveland Scene

Cuyahoga County Ranks Worst In Ohio For Low Birthweights (3/14/2018) Ideastream

Ohio farmers fear retaliation from tariffs (3/14/2018) Dayton Daly News

What you should know: Ohio’s proposed merger of education, training agencies moving quickly (3/13/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Is 16 years old too young to drive? Ohio lawmakers consider upping age for a license (3/13/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Transparency, voter voice concerns spark opposition to state education merger, limits to board (3/12/2018) Plain Dealer

New Ohio education goals put emotional health, critical reasoning and job skills on par with English and math (3/12/2018) Plain Dealer

Political barriers still daunting for Ohio women (3/10/2018) Dayton Daily News

Ohio’s natural-gas production rose in 2017, but ample supply meant low profits (3/9/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Education merger bill attracts overflow crowd of opponents (3/8/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Federal plan calls for phosphorus reductions to improve Lake Erie water (3/8/2018) Toledo Blade

One University Circle prepares to open its doors in April (3/8/2018) Fresh Water

MetroHealth transformation project set to bring major changes to surrounding neighborhood (3/6/2018) News5

Can This Judge Solve the Opioid Crisis? (3/5/2018) New York Times

Ohio wants to improve school security after Florida shootings, but officials have no plan yet (3/4/2018) Plain Dealer

State of the State: Job prospects and quality of life improve, economy slow to recover (3/4/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Cleveland Wants to Connect the Dots with Hundreds of Miles of Greenways (3/2/2018) Next City

The middle class is getting left behind. And it’s happening in Ohio at a higher rate than other states (3/1/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Ohio casinos: They’ve fallen short of projections, and here’s why (3/1/2018) Cincinnati Enquirer

Cleveland-area house prices ended 2017 up 3.5 percent, Case-Shiller finds (2/27/2018) Plain Dealer

Ohio Joins Cities, Counties, Other States In Filing Lawsuit Against Prescription Pill Distributors (2/26/2018) Ideastream

Rowing center, RTA’s Brookpark Station on Greater Cleveland Partnership’s wish list for capital budget (2/26/2018) Cleveland.com

Will Euclid’s new master plan reboot an aging, inner-ring suburb? (2/25/2018) Plain Dealer

Republican Ohio governor candidates support arming teachers to help prevent school shootings (2/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Planned Landfill Solar Farm is Expected to Save Money for Cuyahoga County (2/21/2018) WKSU

Some Ohio Community Colleges Could Soon Offer Bachelor’s Degrees (2/20/2018) WOSU

MAY 8, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTION Issues List from the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections (2/19/2018)

MAY 8, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTION Candidate List from the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections (2/19/2018)

Northeast Ohio Angling For Piece Of Multibillion-Dollar Film Industry (2/19/2018) WOSU

Ohio will try to exempt residents from Obamacare mandate to get insurance, and add work requirement for some on Medicaid (2/16/2018) Cleveland.com

MetroHealth’s finances are looking good (2/16/2018) Modern Healthcare

NOACA signs agreement with Hyperloop Transportation Technologies to explore Cleveland-Chicago routes (2/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Helping students? Or power grab? Governor would take power from elected state school board members in merger (2/15/2018) Plain Dealer

Opportunity Corridor is back on track for 2021 completion after delay caused by taxpayer lawsuit (2/14/2018) Plain Dealer

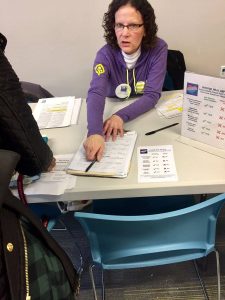

Half of Ohio is an ICE ‘Border Zone’ — Here Are the Rights Immigrants Should Know (2/9/2018) Cleveland Scene

Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish is unopposed for re-election (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Four judges file for two Ohio Supreme Court seats (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Down ticket Ohio races feature a few May primaries (2/7/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio Senate passes bipartisan congressional redistricting plan (2/5/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland Hopkins to update master plan in wake of dramatic changes at airport (2/4/2018) Plain Dealer

Will lack of LGBT protections cost Ohio Amazon HQ2, other business? (2/3/2018) Columbus Dispatch

State Auditor To Push For One-Time Audit Of JobsOhio (2/1/2018) WOSU

Ohio Supreme Court rules against Cleveland’s efforts at local gun control (1/31/2018) Cleveland.com

Despite state, local efforts, human trafficking jumps by 38% in Ohio (1/30/2018) Columbus Dispatch

Chief Wahoo, the longtime logo of the Indians, will be gone after the 2018 season (1/29/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s inner-ring suburbs still hurting from the housing bust, despite addressing blight (1/28/2018) Plain Dealer

After robust 2017, Port Authority anxiously awaits U.S. decision on tariffs (1/28/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

More Lake Erie walleye caught in 2017 than in 30 prior years (1/26/2018) Buffalo News

FirstEnergy executive: Davis-Besse plant headed for premature closure (1/25/18) Toledo Blade

‘Right to work’ could be on the ballot in Ohio with support from lawmakers (1/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Court-enforced Cleveland police reforms continue to be a mixed bag, monitor says (1/24/2018) Cleveland.com

Ohio among northern states to lose another U.S. House seat after next census (1/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Cuyahoga County seeks two-year renewal of health and human services tax (1/23/2018) Cleveland.com

Davis-Besse, Perry nuclear plants could close as FirstEnergy inks deal with hedge funds (1/23/2018) Plain Dealer

At 100, the Cleveland Orchestra May (Quietly) Be America’s Best (1/22/2018) New York Times

The Secret Amazon Bid Dramatizes a Huge Cultural Problem in Cleveland. The Media Can Do Something About It (1/22/2018) Cleveland Scene

Ohio cities take tax fight with state to court (1/21/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Cleveland Hopkins passenger volume tops 9 million for the first time since 2013 (1/19/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Columbus makes Amazon first cut for second HQ (1/18/2018) Columbus Dispatch

US Supreme Court takes on internet sales tax case with implications for Ohio (1/18/2017) Columbus Dispatch

Controversial mayor’s courts abound in Cuyahoga County (1/17/2018) Cleveland.com

Justice Center to be Cuyahoga County’s most expensive endeavor (1/16/2018) Cleveland.com

Cleveland’s settlement houses persevere, even as they struggle with funding and obscurity (1/16/2018) Cleveland.com

RTA’s Long History Of Reliance On Sales Tax May Be Reaching Breaking Point (1/15/2018) Ideastream

The ‘build it and they will come period is over’ for downtown Cleveland apartment market (1/14/2018) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Charter school failure could be largest in Ohio history (1/12/2017) Dayton Daily News

Why GOP redistricting plan flunks test to rid Ohio of gerrymandering (1/11/2018) Cleveland.com

MetroHealth unveils plan to turn main campus into ‘hospital in a park’ (1/10/2018) Plain Dealer

RTA will make cuts because of lost taxes, counties struggle as well (1/9/2018) Plain Dealer

What attributes should a high school graduate have? It’s not just the “three R’s” anymore (1/7/2017) Plain Dealer

Ohio voter challenges election roll purge in U.S. Supreme Court clash (1/4/2017) Crain’s Cleveland Business

Extended cold snap has water mains bursting around Greater Cleveland (1/4/2017) Cleveland.com

Transportation Official Worries About Funding For Ohio’s Roads (1/3/2017) WOSU

Test scores need to stay in teacher ratings, says Cleveland schools CEO (1/3/2017) Plain Dealer

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson sworn in for record fourth 4-year term in office (1/2/2017) Cleveland.com