The pdf is here

Cleveland 1912: Civitas Triumphant

By Dr. John Grabowski

During Cleveland’s long history a number of periods and a number of specific years stand out as special. For sports aficionados the years immediately after World War II, and particularly 1948 were “the” championship years. For economic historians, 1832, the year the Ohio and Erie Canal was completed, stands out as the beginning of Cleveland’s evolution into a prosperous community with enormous potential for future development. But, what if one were to ask what year, or what period marked the point at which Cleveland became a modern city, one deserving of national emulation or the question as to when did democracy truly triumph in Cleveland? The answer would have to be the Progressive Era of the early 1900s and, perhaps, specifically the year 1912. The choice of 1912 is a bit subjective given the rich history of progressive-era Cleveland and the panoply of reformers, from Tom L. Johnson to Frederick Howe, and Belle Sherwin who played important roles in the period. But 1912 is significant in large part because it was a one of the most propitious times for reform and change in the history of the city, state, and nation, and also the the year in which an altruistic and legally savvy reformer assumed the office of mayor. That person was Newton D. Baker.

Newton D. Baker took the oath of office as major of Cleveland on January 1, 1912. He would serve as mayor for two terms, until 1916, a period in which the city would see a remarkable burst of governmental reform and a spate of what can only be termed “progressive” civic actions on the part of private individuals, organizations and corporations. While it is difficult to separate one year from the others in Baker’s tenure as mayor, 1912 is perhaps the best candidate both because it was his inaugural year as chief executive, and also the period in which the ideals and ideas he espoused also were on the center stage of state and national politics.

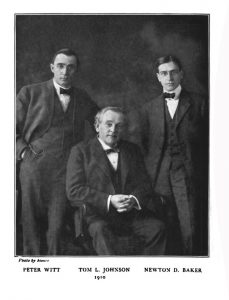

Baker was no newcomer to the local political scene. A lawyer, educated at Johns Hopkins and Washington and Lee, he came to the city in 1899 to work in the law office of former Congressman Martin Foran. Two years later he would become assistant law director in the administration of Tom L. Johnson. A year later, at the age of 32 he would become the city solicitor. Like Johnson, Baker was one of a growing number of individuals who sought to find solutions to a number of problems and issues that confronted the nation in the years after the Civil War. Industrialization, urbanization, immigration, and growing economic disparities severely challenged many of the nation’s foundational ideals, particularly concepts of democracy and equality.

The Progressive Movement or Era, in which Johnson and Baker played nationally prominent roles began in the late 1890s. It was largely urban in origin and its adherents and leaders tended to be well-educated middle class men and women. Their motivations as reformers have been debated by historians for decades with some seeing the progressives working for their own self interests as the native-born middle class was seeing its power and status challenged by immigrant-based political machines in American cities and a wealthy plutocracy whose monopolistic business practices limited opportunities for small scale entrepreneurship. Other historians view the progressive agenda as more altruistic and genuine with roots in the evolving Social Gospel of the late nineteenth century while another interpretation sees the movement as a move to bring order and rationality to all aspects of American life, ranging from the creation of efficient industrial processes to the establishment of professions and professional standards in medicine, law and other occupations, as well as to more scientific means of dispensing philanthropy and dealing with social problems. Whatever their motivations the progressives would advocate a variety of measures to change politics and society, including referendum and initiative, pure food and drug laws, child labor laws, building codes, anti-monopoly legislation, and organized charitable solicitation. They vigorously fought corrupt urban political machines, sought conciliation between labor and capital, and established the social settlement movement within the United States.

All of these motivations can be seen within the reforms undertaken in Cleveland from the 1890s to the 1920s and all are part of the story of the remarkable year of 1912. What happened in 1912 was astounding, but it was not so much revolutionary as evolutionary. Its roots lay in the last decade of the nineteenth century, a period in which the city confronted a considerable number of major changes and issues. One catalytic issue was the economy, particularly the Depression of 1893, which raised issues of labor and capital, the means to bring relief to the poor and unemployed, and the manner in which old solutions failed to address the needs of a rapidly modernizing nation. While the diversity of industry in Cleveland provided some buffer from the national economic decline, events such as the march on Washington by Coxey’s Army which originated in Massillon, Ohio, provided a nearby reminder of the labor unrest that had confronted the nation during previous economic downturns in 1877 and again in the mid-1880s and which might possibly worsen if matters weren’t corrected.

Nevertheless the city continued to grow during the decade and although the rate of immigration diminished briefly in 1894 and 1895, its population rose from 261,353 to 381,768 and its ranking among America cities from 10th to 7th between 1890 and 1900. Although the rise in rank, and the fact that Cleveland had replaced Cincinnati as the state’s largest city was a matter of local pride the rapid growth brought substantial problems in its wake. The most prominent of these was the squalor of older and severely overcrowded neighborhoods near the city’s center, including the Haymarket area, Lower Woodland, and the section around the “Angle” and Whiskey Island on the near West Side. Compounding the matter was the fact that older areas such as these lacked adequate water and sewers. Equally significant was the fact that neighborhoods like these were largely inhabited by the foreign-born and their children, a matter which begged the questions as to how or if an increasingly diverse population could or should be brought into the traditions of American democracy. Ward bosses, such as “Czar” Harry Bernstein on lower Woodland tried to make the newcomers part of his version of urban democracy, a version that was anathematic to many of the long-settled middle class in the city. These situations initiated the first surge of activities in the city which were a combination of personal altruism and idealism and a corporatized search for order and solutions to the problems. The personalized approach was best represented by the rise of the settlement house movement in Cleveland. Hiram House, the city’s first settlement was established in 1896. Its founder, George Bellamy, a student at Hiram College, recalled coming to Cleveland on a survey mission (inspired by a visit to the college by Graham Taylor, the founder of Chicago Commons Settlement) and returning to Hiram to tell his classmates that Cleveland needed a settlement “very badly.” Within four years another four settlements, Council Educational Alliance, Friendly Inn, Alta House, and Goodrich House had been established. Considered “Spearheads of Reform” by historian Allen Davis, the settlements represented grass roots progressive activity often driven by Social Gospel ideals and often fueled by youthful idealism. Their leaders sought to educate and help newcomers adjust to the city at the same time as they confronted political corruption, squalor, and poverty.

There was, however, a more pragmatic and, perhaps, less idealistic side to the rise of progressive reform in the city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and it was led by the city’s Chamber of Commerce. Its agenda fit neatly into the side of the Progressive Movement that sought order, rationality, and efficiency. The businessmen who constituted its membership were familiar with these concepts having often applied them to their own enterprises and in doing so following the teachings of Frederick W. Taylor who pioneered scientific management in the 1880s. The work of various Chamber committees led to the creation of a series of bathhouses in areas that lacked household plumbing; a rational housing code for the city; and a system of charitable giving which would eventually lead to the Community Chest and today’s United Way. The Chamber was also key to the creation of the “Group Plan Commission” which led to the building of the Mall with its orderly arrangement of major civic buildings in the Beaux Arts style. The Mall was, perhaps, the city’s first major urban renewal process as it replaced a declining neighborhood reflected unfavorably on the city. One can debate the motivations of the members of the Chamber of Commerce. Certainly, there was a touch of reform and altruism to their actions, but they also knew that others, including members of the Socialist Party and single taxers were suggesting alternative solutions to the problems that plagued growing urban industrial centers such as Cleveland.

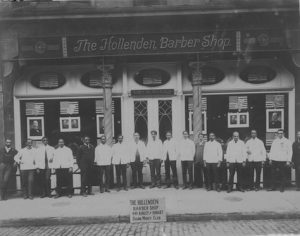

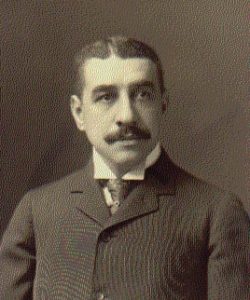

It was, however, a businessman turned politician who eventually came to symbolize progressive reform in Cleveland. Tom L. Johnson built a personal fortune by operating street railways which were, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, hugely lucrative private enterprises franchised by the cities in which they operated. He began his career in Louisville, then operated lines in Indianapolis and lastly in Cleveland in 1879. He moved to the city ca. 1883. Wealthy, with a home on Euclid Avenue, Cleveland’s Millionaire’s Row, Johnson, Like Saul on the road to Damascus, underwent a conversion experience. He read Henry George’s works and became an advocate of the single land tax and free trade — proposals that were frightening to his economic and social peers. Johnson would then spend the remainder of his life, and the better part of his fortune trying to reform society through political action, first as a US Representative from the city’s 21st district (1890-1894) and then as a four-term (1901-1908) mayor of the city, the office in which he received national and international notice for his reforms. He was characterized by journalist Lincoln Steffens as follows” “Johnson is the best mayor of the best governed city in America.”

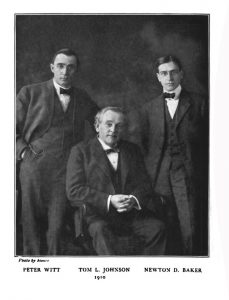

Johnson was one of several US mayors, including Hazen Pingree of Detroit and Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones and Brand Whitlock of Toledo who came to epitomize the rise of progressivism on the municipal level. Today their names and achievements are common to many historical texts on the era. The hallmarks of Johnson’s mayoralty in Cleveland were an expansion of popular democracy, the professionalization of governmental functions and an advocacy of the public ownership of services, including utilities and urban transit. He succeeded in the first two – his tent meetings and very “populist” mayoral campaigns were unlike any seen in the city before and the people he chose for his cabinet to manage legal issues, public safety, water services, and the penal system were professionals with the best credentials, rather than campaign supporters and political hacks. However, his plans and hopes for municipal ownership of utilities and urban transport never fully succeeded. Indeed, his campaign for control of the street railways and especially the imposition of a standard three-cent fare engendered strong opposition, and eventually led to his defeat in 1908 by a public grown weary of the issue.

Johnson also struggled with the matter of restructuring the system of government for Cleveland. While he was able to hire the best managers, the statehouse, using the then current 1851 state constitution, dictated the manner in which cities could design their systems of offices and responsibilities as well as their overall structure of representation and governance. The state system was antiquated and could not match the needs of growing urban areas – the problem was not unique to Cleveland nor to Ohio and it represented part of a growing gap between rural-dominated statehouses and polyglot industrial cities. The solution was “home rule,” that is the ability of the citizens of a particular municipality to select the system that best suited their needs. Johnson campaigned on a platform of home rule but here too, was unable to achieve it before his defeat by Republican Hermann Baehr in 1908.

Yet his defeat in 1908 did not signal an end to progressive reform in the city. By the time Johnson had left office the movement was firmly embedded not only in the city but in the nation. The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, which also ended in 1908, had given a progressive hue to national politics. Most important for Cleveland, however, was that Johnson’s acolytes, particularly Newton D. Baker, remained in the city and remained committed to concepts of democratic and social reform. Likewise, but from another perspective, the business-based focus on rationality and order accelerated, and, for whatever its drawbacks, would continue to effect significant changes to the manner in which the city, and most particularly, its benevolent institutions operated.

The major thread of local continuity was Newton D. Baker. Baker continued to serve as City Solicitor during the Baehr administration and, upon Johnson’s death in 1911, he assumed leadership of the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party. While Baker shared the same idealistic zeal of his mentor, Johnson, he more truly fit the mold of the typical progressive and, by virtue of that, was became a more effective leader in the movement. Unlike Johnson, he had a university education and was professionally trained as a lawyer. Unlike Johnson, he had never garnered wealth, but at that time remained a member of the middle, professional class. Also, Baker was young. Johnson was 47 when he became mayor in 1901, Baker was 30 when he joined the administration that year, an age more in concert with the group of young social workers and civic advocates with which he socialized. Among these was a college classmate, Frederick Howe, who was active in a variety of local reform organizations including Goodrich Settlement House. Certainly, his tenure with Johnson was one akin to apprentice and master in regard to politics, but Baker learned quickly and his ability as an articulate, informed public speaker made him an asset to the administration and eventually would, along with his deep understanding of the law, form the basis for a political career which would eclipse that of his mentor. Baker ran for mayor in 1911 against Republican businessman, Frank G. Hogan, and won handily.

Baker’s assumption of the office of mayor in 1912 was one of three seminal political events that year, each heavily colored by the urge for progressive reform. The most visible was the impending US Presidential campaign which would find three candidates seeking the office: Democratic Woodrow Wilson; Republican William Howard Taft the incumbent; and the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party candidate, former President Theodore Roosevelt. The other event was a state constitutional convention in Ohio which was charged with redrafting or amending the state’s 1851 Constitution. Baker, as mayor of Cleveland would play important roles in both of these events and in doing so gain stature for himself and his city in the state and nation.

When Baker assumed the office of mayor, Cleveland was the nation’s sixth largest city and its population was over 600,000. Baker’s campaign had promised more reforms including the municipal ownership urban utilities including gas, electric, street railways, and even the telephone system. He also strongly advocated home rule. His primary goal, however, was something he called “civitism,” a word which he coined and which referred to the creation of a sense of pride in all citizens for their city. It was a pride to be built upon a broad participatory democracy and which would bring in its wake the buildings, cultural institutions, parks and other physical amenities that make a city great. Baker’s margin of victory in 1912, over 17,000 votes, was the largest in the city’s history up to that time. Short in stature (he was only 5’ 6” tall) Baker was not physically imposing, as had been his mentor, Johnson, but he made up for the lack of stature with superb oratorical skills and well-honed abilities as a debater.

Like Johnson he appealed to a broad democracy, holding tent meetings around the city during election periods and speaking at numerous venues for dedications, neighborhood gatherings and other “technically” non-political events. That, along with his substantial plurality allowed him to achieve things that had eluded Johnson. By 1914 Cleveland had is municipal electric provider (today’s Cleveland Public Power). Although street railways were not fully municipalized until 1942, his administration, notably through the efforts of Peter Witt, (Baker’s Commissioner of Street Railways),was able to use municipal oversight to get fares dropped to 3 cents. Baker then went on a “three-cent binge” creating municipal dance halls that offered dances at that price and selling fish from Lake Erie at three cents, the fish being trawled for by city boats. The municipal electric plant also offered 3 cent lighting!

Baker’s first year in office set a tone for other events that enhanced the progressive nature of the community. The West Side Market, the site of which had been purchased by the city under the Johnson administration in 1902, dedicated its new modern facility in 1912. Designed by the noted architectural firm of Hubbell and Benes, the building was the epitome of a modern market, sanitary, attractive, and hugely efficient. In October 1912, the emphasis on democracy and open civic debate favored by progressives such as Johnson and Baker came into its own with the founding of the City Club of Cleveland. On the same day, January 1, that Baker took office, the new County Court House, a landmark of the Group Plan opened. Baker’s two terms of office would see the construction of its counterpart, the City Hall, which would open in 1916, the year after Baker left office. The site of the old city hall, on Superior Avenue, then became that for the new building of the Cleveland Public Library. Citizens approved a bond issue to pay for the new building in 1912. It would open in 1925.

Paralleling these civic reforms was a continued growth of industry and entrepreneurship in the city, something attributable, in part, to the efforts of the Chamber of Commerce to stabilize the chaos of urbanization in Cleveland. Although one can pinpoint several major industrial developments in the city during 1912 – including the expansion of the Otis Steel Works into a major new plant in the Flats south of Clark Avenue, statistics for the decade as a whole show an enormous growth in productivity. The values of industrial products made in Cleveland was $271,960,833 in 1910, it rose to $350,000,000 in 1914, and after World War I to $ 1,091,577,490 in 1920. That growth did not, however, come without continued conflict between capital and labor. In 1911, 4,000 workers in Cleveland’s large, and growing garment industry went on strike. Their action failed, but in ensuing years manufacturers tried to stave off unionization by offering benefits, lunchrooms, recreation and employee representation in decision making. This variety of corporate paternalism was considered progressive at the time, but that definition is debated by some contemporary historians.

What made 1912 a seminal year for the city was not simply what took place within its borders, but the influence it wielded on the state and national level during that year, influence largely attributable to its mayor. In 1910 Ohio voters had called for a new constitutional convention. The last attempt to modify the State’s primary document had ended in failure in 1873 and the 1851 constitution that remained in place was totally inadequate to the needs of the state, most particularly those of its urban areas. The convention opened in Columbus in January 1912. The delegates to the conference chose not to change the Constitution itself but rather proposed a series of amendments to be put before the electorate. The forty-two amendments they offered to voters in a September 3 election encompassed a substantial portion of the progressive agenda. They called for initiative and referendum as a means to bring the peoples’ voice directly to lawmaking; home rule which would allow communities of over 5,000 people to establish their own systems of governance; labor reforms including the establishment of a minimum wage, workman’s compensation and a provision to allow the legislature to set working hours; an expanded state bill of rights; a line-item veto for the governor; and the right for Ohio Women to hold certain state offices and to vote.

Mayor Newton D. Baker was one of the principal advocates for the progressive agenda of the convention, speaking before the delegates drafting the amendments and then stumping for proposals prior to the election. He was in excellent company – others who spoke included Brand Whitlock, the progressive mayor of Toledo, Ohio, Hiram Johnson, the governor who had made California a bell weather progressive state and Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft, who would go on to become the candidates in one of the nation’s most critical Presidential contests in the fall.

In September voters approved thirty-two of the proposed amendments. Among those rejected was women suffrage, but all of the major amendments relating to labor, direct democracy, and home rule passed. Subsequent state legislation would make these progressive concepts a reality. Baker’s role as advocate was critical to the enormous liberalization of the state’s constitution and this brought national notice and credit to him and his city.

The Presidential campaign then served to heighten his stature. Then as now, Ohio was a critical electoral state and then as now, the vote in Cuyahoga County had significant impact on statewide election results. The contest that year was arguably the last in which a third party candidate had legitimate hopes for victory. That candidate was former President Theodore Roosevelt. He had sought the nomination of his original party, the Republicans, but was defeated by William Howard Taft, the man whom he had selected as his successor has President in 1908 but whose conservative actions had irritated him and other progressive Republicans. Interestingly, it was a set of adroit maneuvers by Cleveland Republican Party boss, Maurice Mashke, that loaded the Ohio delegation at the convention with votes destined for Taft thus ensuring Roosevelt’s loss of the nomination. Roosevelt then bolted the party, and became the candidate of the new Progressive (or Bull Moose) Party. Baker, however, had strong ties to the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, who would win the three-way contest. He had taken a class taught by Wilson at Johns Hopkins University and had remained close to Wilson ever since. Both were intellectuals who had entered the political arena as reformers; Baker, of course, in Cleveland and Wilson, the President of Princeton University as the reform governor of New Jersey in 1911. The connection was valuable to both – Baker made a critical speech at the Democratic Convention in Baltimore that helped Wilson win the nomination and Wilson would invite Baker, in several instances to become part of his Presidential administration. Although Baker declined the initial overtures, wishing to continue his service as mayor of Cleveland he would, after he had left office in 1916, accept the invitation to become the Secretary of War.

Baker had many reasons to wish to stay in Cleveland, foremost among them was the chance to use the new Home Rule amendment to create a special city charter for Cleveland. By doing so he would he would fulfill one of his mentor, Tom Johnson’s major goals – the creation of a modern, rational system of governance specifically suited to the needs of Cleveland. The process began in 1913 with the election of a special commission to decide on the new governmental structure. Their proposal went to the voters in 1914 and was approved by a margin of two to one. With the system in place and Baker elected to a second term in office, Cleveland remained one of the nation’s premier examples of progressive government.

The restructuring of government and Baker’s national prominence were not the only factors that brought notice to the city. It continued to exhibit “civitas” on other fronts, both philanthropic and cultural. Frederick Goff’s establishment of the Cleveland Foundation in 1914 made the city the pioneer in the creation of community funds. The establishment of the Federation For Charity and Philanthropy (the successor to the Chamber of Commerce’s Committee on Benevolent Institutions and the predecessor to the Community Fund) in 1913 marked the beginning of federated charitable solicitation and distribution. The creation of a city Department of Welfare under the auspices of the new Home Rule charter in 1914 added to the evolving modern social service infrastructure. Two years later a Women’s City Club would come into being, evidence of the gender divide that continued despite the progressive impulse. The same year saw the opening of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the first performance at the Cleveland Playhouse.

Within another year, however, the United States would join the great European war and that experience would both overshadow and, according to some historians, tarnish the rise of progressivism in the United States. One of its most visible consequences for Cleveland was the elevation of Newton Baker to a place of international prominence. Baker had left the mayor’s office in 1916 to establish his own law firm (it exists today as Baker Hostetler), but within months he was asked by President Wilson to join his cabinet as Secretary of War. He accepted, taking a leave of absence from the law firm. Within a year he found himself undertaking the Herculean task of creating, training, and equipping an army of two-million and then transferring it to Europe. The task involved logic, political challenges, and the expenditure of vast amounts of money. In true progressive style he assembled a team of expert, efficient managers and, by and large, performed a logistical and political miracle.

While the “war to end all wars” ended successfully for the US and its allies, it was followed almost immediately by a period of disillusionment. The rationale for entering the war was questioned as was the strict regimentation of society for the war effort, a regimentation that often curtailed individual liberties and which was sometimes colored by propaganda-driven biases and prejudices. In some ways this reflected badly on that aspect of progressivism which focused on order and rationality. Baker was caught up in this maelstrom of second thoughts after the war. He stumped enthusiastically for President Wilson’s campaign to have the United States become a member of the League of Nations – a concept that very much reflected on the social idealism of progressivism. The campaign failed and the US entered the 1920s seeking “normalcy,” which in many ways seemed to counter the old zeal for reform and change.

Some historians see the war and the decade that followed as the end of the Progressive Era, while others argue that many progressives continued to be influential, noting that a number would rise to prominence, ideals intact, within the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Baker’s position during this period seems ambiguous. He remained active on the political front, serving as the chairman of the county Democratic Party until 1936 and in 1932 he was considered a viable candidate for the Democratic Party nomination for President. But during this time, when the bulk of his time was devoted to his law firm, he arguably became increasingly conservative politically and was, at times, at odds with the Roosevelt Administration. He objected, in particular, to the expansion of Federal power and programs during the New Deal.

Whether or not Baker remained a “true” progressive until his death in 1937 or whether or not the movement ended in the early 1920s or later, are interesting and important historical questions. However, there is no question as to the impact of the legacy of the Progressive Era in Cleveland and, particularly, that of the events of 1912 on the subsequent history of city. For example, the surveys conducted by the Cleveland Foundation during its early years helped shape a number of areas of social policy, including public education in the 1920s. The establishment of Home Rule allowed Cleveland to create a city manager form of government in 1921. The city manager system was a true progressive ideal as it attempted to move politics out and professional administration into the running of a city. It functioned from 1923 to 1931, when the Depression and patronage politics undermined it. Today examples of the progressive legacy abound ranging from Mall, the Metro Parks system pioneered by William Stinchcomb, in 1917 to the set of arts and cultural institutions that set Cleveland apart from other cities. In regard to organized charity and philanthropy the annual United Way fund drive and institutions such as East End Neighborhood House, Goodrich-Gannett, and Hiram House Camp which had their beginnings in the period continue to serve the community today. Perhaps most importantly, the principal of direct democracy, made possible by initiative and referendum remains alive and viable, as was demonstrated in the statewide referendum relating to the bargaining rights of public employees on the 2011 ballot.

Certainly, the selection of 1912 as one of “the” years in Cleveland’s history can be debated. However, now, a century thereafter, the degree to which the events that took place during it and in the surrounding era still shape daily lives in the city and state is simply remarkable. But, perhaps of greater consequence is the fact that the ideals and persistence of those who used their intellect and altruistic ideals to promote change 100 years ago can and should, continue to inspire us.

To see lecture that supported this essay, click here