John D. Rockefeller aggregation

Her Fathers’ Daughter: Flora Stone Mather and Her Gifts to Cleveland by Dr. Marian Morton

Her Fathers’ Daughter: Flora Stone Mather and Her Gifts to Cleveland

By Dr. Marion Morton

Cleveland’s best-known woman philanthropist took no credit for her generosity: “I feel so strongly that I am one of God’s stewards. Large means without effort of mine, have been put into my hands; and I must use them as I know my Heavenly Father would have me, and as my dear earthly father would have me, were he here.” [1] So Flora Stone Mather described the inspirations for her giving: her Presbyterian belief in stewardship – serving (and saving) others – and the example of her father, Amasa Stone. But she expanded her role as grateful daughter, moving beyond philanthropy into political reform and institution-building.

Flora Stone, born in 1852, was the third child of Amasa and Julia Gleason Stone. Her family – parents, brother Adelbert, and sister Clara – moved to Cleveland from Massachusetts in 1851. Her father, a self-taught engineer, built churches, then bridges and railroads, which made his fortune. He arrived in Cleveland as superintendent of the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad, which he had built with two partners. He subsequently directed and built other railroad lines and invested in the city’s burgeoning industries and banks. Thanks to its railroads and lake shipping, petroleum refineries, and iron and steel mills, Cleveland would become an industrial giant.

In 1858, Stone built an elaborate Italianate mansion on Euclid Avenue, a sign that he had arrived socially and financially. He became an ardent Republican and an enthusiastic supporter of the Union side of the Civil War. The war boosted Cleveland’s industries and made Amasa even richer. He kept his son Adelbert out of the Union Army, but lost him anyway when the 20-year-old student at Yale drowned on a school expedition in June 1865.

Julia Gleason had worked as a seamstress before her marriage, but her husband’s financial success and social position meant that daughters Flora and Clara were destined for lives of privilege, defined as marriage and family, in keeping with nineteenth-century ideas about woman’s nurturing and innately domestic nature.

Flora seemed fitted by personality and upbringing for this role. “Small in stature and fragile in health,” “plain and unassuming” in her appearance and habits, [2] she was above all, modest, self-effacing, and compassionate. She dutifully participated in the conventional social life expected of Euclid Avenue women: dinners, receptions, teas, walks and carriage rides, charity benefits, and visits to her affluent, congenial neighbors. Yet she had a lively intelligence and a keen curiosity, honed by her rigorous education and travels abroad. Her intellect and energy made her a leader among her peers even as a young adult: “’Wait until Flora comes. She will know just how to go ahead,’” said her friends.[3] She also had an adventurous spirit, confessing to her fiancé: “I do like to meet new people.”[4] And meet them she did.

Amasa Stone valued education for his daughters – perhaps to enhance their (and his) social status or perhaps to enhance their intellects. He was a funder and the builder of the Cleveland Academy, a private girls’ school, which opened in 1866 across from the Stones’ Euclid Avenue home. Both Clara and Flora attended. Their demanding college preparatory education relied on both Biblical texts and current events and emphasized speaking in public as well as writing.[5] Headmistress Linda Thayer Guilford also taught her young students that they had a moral responsibility to the less fortunate around them.

And there were plenty of the less fortunate in post-Civil War Cleveland. Its population had doubled during the war and continued to grow – 92,829 in 1870 and 160,146 in 1880 – , swelled by immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and soon from all over Europe, as well as by native-born men and women from small towns and villages who saw possibilities in this bustling city on Lake Erie. Often lacking the skills for urban life or earning a living in the city, however, new arrivals often fell upon hard times. The Cleveland Infirmary (or public poorhouse) sheltered – grudgingly – absolutely destitute families. Those who had at least a roof over their heads received an ungenerous supply of food and clothing at the backdoor of the Infirmary. In this almost complete absence of public assistance, private charities, all faith-based, stepped in to help their co-religionists.

Immigrants also turned a small homogeneous town into a prospering city with neighborhoods differentiated by class, ethnicity, or religion. But in the second half of the nineteenth century, before the widespread use of the streetcar and then the automobile allowed the well-to-do to flee the city, these neighborhoods often adjoined one another, so that the less fortunate were not hidden from their more fortunate neighbors.

The population growth that created visible poverty also created great wealth for some: men like Amasa Stone who arrived in Cleveland at the right time with the right skills. And like Stone, a handful became the philanthropists who created Cleveland’s enduring cultural, educational, social welfare, and medical institutions, as well as its recreation facilities. Some of the magnificent gifts of these late nineteenth-century industrialists and bankers still bear their names: Gordon Park, Wade Park Lagoon, Severance Hall, Rockefeller Park, the Mather Pavilion of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University.

All these big donors were men. It would have been almost impossible for a nineteenth-century woman to earn this kind of money. Women acquired wealth by inheriting it or marrying it.

Flora Stone Mather did both. Her marriage in 1881 to Euclid Avenue neighbor Samuel Mather was a love match that brought the couple four children – Samuel Livingstone Mather (born in 1882), Amasa Stone Mather (born in 1884), Constance Mather (born in 1889), and Philip Richard Mather (born in 1894). The Mathers were a more distinguished family than the Stones, dating their American origins back to the famous Puritan ministers, Increase and Cotton Mather. Samuel’s father, Samuel Livingston Mather, came to Cleveland in 1843 to take charge of the family’s holdings, established by his own grandfather, Samuel Mather Jr., a stockholder in the Connecticut Land Company that settled the region. [6]

Although born into a wealthy family, Flora’s husband had made his own fortune. In 1869, he had permanently injured his arm while working in his father’s Michigan ore mines and did not attend Harvard as he had planned. Instead, Samuel continued to work for his father’s company, Cleveland Iron Mining Company, and then founded Pickands Mather, a rival supplier of iron ore and transportation to the steel industry. He also held directorships in several iron and steel companies and banks. When Samuel died in 1931, he was considered the richest man in Ohio although the Great Depression had diminished his wealth. [7]

Amasa Stone’s death in 1883 left Flora an independently wealthy young woman. Stone committed suicide, depressed by his own failing health, his son’s death, and the tragic collapse in 1876 of one of his railroad bridges, which killed 92 passengers and ruined Stone’s reputation. [8] Flora and Clara each inherited $600,000; their husbands, author-diplomat John Hay and Samuel Mather, $100,000, plus whatever money was left over after Stone’s debts and other bequests were paid. [9]

Flora had enough money during her lifetime to make dozens of gifts to local charities – from the Visiting Nurse Association and the Humane Society to the YMCA, the Home for Aged Colored People, and Hathaway Brown School. When she died in 1909 of breast cancer, she left money to a wide range of educational institutions, including Lake Erie College and Tuskegee Institute, various Presbyterian missionary groups, Cleveland Associated Charities, and the Association for the Blind.[10]

Her most compelling interests and her most generous gifts, however, were shaped by her private religious faith that found public expression in serving those in need.

The Stones belonged to First Presbyterian (Old Stone) Church, centrally located on Public Square, close to the Stones’ Euclid Avenue home. The church, founded in 1827, boasted a socially and politically prominent congregation. Like most other wealthy Protestant churches, Old Stone sold or rented pews to its members. In 1855, when the Stones were members, almost half of its pews cost more than $400 a year; eight cost $1,000.[11] Obviously, this custom discouraged membership by the less wealthy.

Perhaps to compensate for the high price of its pews, the congregation also established a tradition of stewardship. Its members established the Western Seamen’s Friend Society in 1830, one of the city’s first charities, which built a chapel and organized a Sunday school to promote the physical and spiritual needs of the men who worked on the canal and the lake.

Although the leadership – lay and clerical – of Protestant churches was male, women carried on most of the institutions’ charitable activities. (They also did most of the fund-raising.) These allowed women a socially sanctioned entrance into the world beyond home and family. Led by Rebecca Rouse, the women of Old Stone founded the city’s first orphanage, the Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, in 1852. This is now Beechbrook, a residential treatment center for children. In 1863, the women established a home for “poor and friendless people” – later called the “Protestant Home for Friendless Strangers” – who were so new to town that they were ineligible for the city Infirmary. [12] Amasa Stone became the first in his family to donate money to this institution, which evolved into Lakeside Hospital and eventually University Hospitals.

Like other Protestant churches, Old Stone experienced waves of religious revivalism in the last decades of the nineteenth century that gained the institution new members and new enthusiasm. In 1866, for example, its pastor, Rev. William H. Goodrich, led a “powerful revival” with “marked indications of the presence of the Spirit” in the Young People’s Meeting.[13] Flora, then an impressionable 14, may well have felt that Spirit. [14]

In 1867, Flora and Clara joined the newly formed Young Ladies Mission Society. The young women did their missionary work in the working-class neighborhood just to the north of the church where they sewed garments and raised funds for the mission church that became North Presbyterian, originally at E. 41st St. and Superior Ave. [15]

This missionary spirit also infused the temperance movement of the 1870s. Temperance was probably the most popular reform of the nineteenth century as American cities grew rapidly. Too much alcohol in a country village was one thing; too much in a congested urban neighborhood was another – obviously more harmful to persons and property. Drinking was also associated with immigrants, especially Irish and Germans, not always welcomed by native-born Clevelanders. And to enthusiastic Protestants, conversion to temperance was the first step to finding salvation and true religion, a belief reinforced by the opposition to temperance by some Catholics.

Temperance had particular appeal to women since male abuse of alcohol harmed women and children. In spring 1874, “praying bands” of Cleveland women descended upon local saloons, pleading with saloon keepers and customers to forswear alcohol. Weeks later, the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was formed in Cleveland; in the last decades of the nineteenth century, it became the largest woman’s organization in the country.

The local branch of the WCTU founded several institutions intended to save men, women, and children from the evils of alcohol. [16] Two have survived: Rainey Institute and Friendly Inn, both neighborhood centers in inner-city Cleveland.

Temperance provided Flora with her first foray into public life as vice president (1874-1876), then president (1877-1881) of the Young Ladies Temperance League (YLTL). The young women were more decorous than the “praying bands,” although equally pious. As president, Flora led their formal meetings, held in various Protestant churches, which began with prayers and featured hymns, and Bible readings. Their group’s stated goal: to stand “against the use of intoxicating liquors [and] to aid in creating an enlightened Christian public sentiment” on the subject. All members took the pledge of total abstinence.[17]

Like the WCTU, the young women believed that the salvation of the soul was closely connected to the salvation of the body, and like their elders, they established institutions for less fortunate women. The first, in 1875, was a lodging house “for friendless young women dependent upon their own exertions for support,” which provided “a refuge from temptation” while jobs and permanent housing were sought. “Nearly all” the young women were “either directly or indirectly, sufferers through the crime of intemperance.”[18] The home sheltered only Protestants and only “the better class of young women … seamstresses, housekeepers, clerks, nurses …” Flora drew up the house rules, which included attending Protestant religious services. [19]

More inclusive and of more lasting importance were the league’s institutions for children. The YLTL briefly took responsibility for a “charity kindergarten for “twenty-one little waifs.” Out of this project in 1880 grew a day nursery. Flora had visited such a nursery in New York City and encouraged the group to start “a similar enterprise” in Cleveland. [20] Here Flora developed personal connections with poor children and their mothers: “”[I] had such a sweet time at the Nursery…. I sat by the fire rocking a cradle and singing to a tired little boy. Then the mothers came for their children and I had a little talk with each one.’”[21] The nursery took all children, regardless of their religious background.

In 1882, the Young Ladies Temperance League became the Young Ladies Branch of the Woman’s Christian Association, whose sole purpose was to establish day nurseries for the children of working mothers. Flora served as the group’s first president. She enlisted the financial support of her former Euclid Avenue neighbor, John D. Rockefeller. [22] In 1888, she herself donated the site of the nursery she named “Bethlehem” to connect it “with the childhood of Christ.” [23] This was one of several day nurseries that the group eventually maintained; the others, however, were named for their benefactors like the Hanna and Wade families. A Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter painted this charming portrait of the Perkins day nursery: “cool, clean, airy rooms filled with bright-faced, happy children” who received meals and medical attention as well as lessons in good behavior; mothers paid five cents a day or whatever they could afford. [24]

In 1894, Flora’s organization became the Cleveland Day Nursery and Kindergarten Association, which operated day nurseries and kindergartens all over the city and trained teachers for public kindergartens. As the Cleveland public school system established its own kindergartens, the association gradually closed theirs but continued to operate day nurseries until it was absorbed into the Center for Families and Children in 1969. Hanna Perkins Center for Child Development is descended from the association.

Although initially inspired by her pious desire to serve the less fortunate, Flora’s next project moved her in the direction of changing the society in which they lived. In 1897 Flora founded and funded Goodrich House, the social settlement at E. 6th and St. Clair Avenue, around the corner from Old Stone and named for her former pastor. Its “object,” Flora wrote, “shall be to provide a center for such activities as are commonly associated with Christian Social Settlement work.” [25] Although a separate institution, the settlement grew out of Old Stone’s clubs and classes for neighborhood children. The first president of the settlement’s board of trustees was the current pastor of Old Stone, Hiram C. Hayden. The settlement’s first director, Starr Cadwallader, was a graduate of Union Theological Seminary.

Settlement houses often had denominational connections. Cleveland’s first settlement, Hiram House, was an offshoot of Hiram College, a Disciples of Christ institution, and was directed by George Bellamy, an ordained minister. The Council Educational Alliance, which evolved into the Jewish Community Center, was initiated in 1899 by the National Council of Jewish Women; Merrick House, in 1919 in the Tremont neighborhood, by the Catholic Christ Child Society.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer in June 1897 waxed ecstatic about Goodrich House, the gift of “Cleveland’s most distinguished woman philanthropist, Mrs. Samuel Mather.” The activities within the “handsome three-story building of brick with stone trimmings and imposing entrances” were “infused with the Christian spirit although no effort is made to prejudice its members in religious matters.” [26]

Settlements sought to solve the pressing problems of urban poverty and social dislocation by easing the transition of immigrants into urban life, expanding upon the faith-based activities spawned by churches and the temperance movement with secular lectures, services, and classes for adults as well as for children. Goodrich House, for example, had a gymnasium, a bowling alley, public baths and a laundry, classes in choral singing, several clubs for boys ( the Garfield and Franklin clubs) and for girls (the Sunshine, Rosebud, and Little Women clubs). [27]

Settlement residents were usually single, middle-class, educated men and women who lived in the settlement in return for leading classes or other activities with its working class neighbors. Goodrich House’s early residents included future Cleveland mayor and U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and reformer-author Frederic C. Howe. Howe later recalled: “Residents … had good food and comfortable rooms; they enjoyed a certain distinction because of their good works.” [28]

Settlements launched the careers of many Progressive reformers because what the residents learned first-hand about the difficult lives of the poor often encouraged them to challenge the political and economic status quo. Goodrich House became “perhaps [the] most liberal settlement” in Cleveland, providing a “public forum for the discussion of social reforms.” [29] In this context, Howe, like Baker, went into reform politics, as did Cadwaller.

By then married with four small children, Flora did not become a resident of Goodrich but was fully engaged in its activities from its beginnings to the end of her life. Its organizational meetings were held at her Euclid Avenue home. She wrote to well-known reformer Jacob Riis for suggestions for a director. He couldn’t help her out, but when Goodrich House opened in April 1897, she invited Riis to its opening; he regretfully declined. [30] She served on the settlement’s House Committee that oversaw its residents and on its executive committee. She provided also for the settlement’s upkeep. Staff had to insist on sticking to a budget so that she would not simply pay all the bills herself.[31] Samuel served on the board of trustees.

As the downtown neighborhood commercialized, Flora participated in the discussion to sell the elaborate building in 1907 and to move farther east to E. 31st St. Flora’s settlement, now located at E. 55th St. and St. Clair, has been renamed Goodrich-Gannett Neighborhood Center after Alice P. Gannett, the settlement’s director from 1917 to 1947. It provides a wide range of programs and services for children and adults as it did when Flora first founded it.

Responding to what she too had learned about the urban poor at Goodrich, as well as in her earlier temperance work, in April 1900, Flora urged the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce to “try to improve the conditions of labor.” “Mrs. Samuel Mather Will Co-operate Very Substantially,” exclaimed the Cleveland Plain Dealer on its front page, when Flora promised to pay the salary of someone to take charge of investigating “working people’s conditions and surroundings in stores, shops, and factories.” [32] Within weeks, however, she decided instead to form at Goodrich House the Consumers League of Ohio (CLO), a local chapter of the National Consumers League. Flora served on the local league’s executive committee from its founding until 1907 when she was made an honorary vice-president.

The league’s goal was to improve the working conditions of women and children: to limit the hours of work, to guarantee a minimum wage, and to ensure that factories, mills, and offices were safe and sanitary. In 1900, more than a third of Cleveland’s female work force (10,600 women) were factory operatives; they worked in all industries but were concentrated in textiles, cigar factories, and laundries. A study in 1908 provided shocking details: women and girls in laundries got paid less than $5 a week; work in candy factories was dangerous and filthy (for both workers and consumers); in garment factories, men did the skilled work and got paid twice what women did.[33]

Although it had no connections with organized religion, the CLO’s concern for women and children had been Flora’s since her days as a temperance activist. In 1905, league president Marie Jenney Howe maintained that the local CLO grew out of Flora’s “friendship” with Florence Kelley, the founder and first general secretary of the national organization. [34] Flora may have met Kelley when she was a resident at Chicago’s famous settlement, Hull House, from 1891 to 1899, just as Flora was making her plans for Goodrich House. Kelley, a Socialist, was also an outspoken activist and reformer. The CLO moved Flora even more decisively from philanthropy into reform politics.

League members used their considerable social status and economic power as middle-class consumers to apply pressure on employers to improve conditions in their shops and factories. For example, in 1901, Flora, with CLO president Belle Sherwin, asked retail store owners to close at noon on Saturday to give their workers an extra half-day off. [35] The league also tried to educate the public about wages and working conditions in factories and shops. Employers who met league standards got the league’s “white label”; shoppers were urged to boycott those who did not. Sherwin reported much progress in 1905: “improvement in lunch and toilet rooms for employees, better sanitation in factories, shorter hours for clerks and, best of all, a cultivation of a ‘shopping conscience.’” [36]

Department stores like William Taylor & Co. advertised that many of their goods carried the “white label” – meaning “clean, sanitary surroundings [for workers], the absence of child labor, the proper treatment of employees, the absence of sweat shop conditions.” [37] But CLO members soon realized that voluntary cooperation of employers with the league “did not prove universally successful … [ and] recognized the need for establishing legal standards.” [38] This realization took women like Sherwin and Howe into politics and the suffrage movement.

Flora died before the local suffrage movement was well underway, but in 1905, she ventured again into reform politics when she joined the local committee to work with the National Child Labor Committee. The goal of the committee, established in 1904 and headed by Owen Lovejoy, was to end child labor. Husband Samuel also sat on the committee, as did Rabbi Moses Gries and Belle Sherwin. [39]

In 1908, Flora, with Marie Jenney Howe, Mrs. Newton D. Baker, and others, organized the Municipal School League. Its purpose was “to increase the interest of women in the school ballot … [and] to maintain the representation of women on the school board.” [40] (Ohio women had gotten right to vote for and serve on local school boards in 1894.)

If Flora’s faith-inspired work for women and children led her into the secular world of political reform, her gifts that followed in Amasa Stone’s footsteps helped to transform the small college for men that he had sponsored into a thriving university that educated both men and women.

His gift of $500,000 had persuaded Western Reserve College, founded in 1826, to move in 1882 from the village of Hudson to the city of Cleveland on properties along Euclid Avenue in what is now University Circle. These had been donated by other benefactors for both Western Reserve and Case School of Applied Science, which had been founded in 1881 by Leonard Case Jr., in downtown Cleveland. Stone stipulated that Western Reserve College was to be re-named Adelbert to honor his son and that $150,000 of this gift was to be spent on buildings and that the remainder would be a permanent endowment. It is not clear whether the gift was inspired by Stone’s grief at the loss of his only son or by his rivalry with Case or whether it was intended to atone for the tragic train wreck. In any case, the gift came with strings attached: not only the college’s new name but a new board of trustees chosen by Stone himself. After his death in 1883, the college received another $100,000. [41]

Generous as Amasa had been, Flora and husband Samuel would ultimately donate to the college more than ten times as much. [42] When her father died, she and Samuel had been married only two years and still lived in Amasa’s home. (The couple built their summer home Shoreby in Bratenahl in 1890 and a grander home on Euclid Avenue in 1910, completed after Flora’s death.) Flora must have been deeply grieved at her father’s death and the contempt which many Clevelanders had for him – despite his wealth and social standing. Her gifts to the college – like his – may have been a way of clearing his name and restoring his reputation.

Her first gifts were to Adelbert College: an endowment in 1888 of $50,000 and $2,500 to the library fund, to which Samuel also contributed. In 1889, she endowed a chair in history. The Cleveland Plain Dealer haled the “MUNICIFENT GIFT,” but Flora, always modest, “treated the subject lightly and impatiently said the sum was so small she didn’t care to speak of it.” [43]

The endowed chair was named for Haydn, then both the college president and Flora’s pastor at Old Stone. Almost all private colleges had financial and other connections to religious denominations, and it was common for college presidents to be clergymen.

Haydn ended coeducation at the college. Women had been admitted, beginning in the 1870s. Although their numbers were small, most were excellent students, and they had a champion in then-college president Carroll Cutler, whose daughter Susan was valedictorian of her class. But the women also enemies among the faculty and trustees, who blamed the college’s low enrollment on its female students and feared that the college would become “over-feminized” if it continued to admit women. Cutler resigned, weary of the battle over coeducation. Haydn assumed the presidency in November 1887 and terminated the admission of women shortly afterwards. This decision generated bitter controversy over the virtues of educating women. During his inaugural address, four women, graduating seniors, walked out of Haydn’s presidential inauguration in protest, leaving the college for good and receiving their college degrees elsewhere. Haydn responded by establishing a separate College for Women under the aegis of Western Reserve College in 1888. [44]

The new College for Women thus got off to a rocky start. Its faculty was drawn from Adelbert College, and for three years, they taught the young women for free in a farmhouse at the corner of Euclid Avenue and Adelbert Road. There was originally no dormitory, no proper chapel, and an ill-equipped gymnasium in a barn.[45]

The first significant gifts to the new College for Women came from Flora’s mother ($5,000) and her brother-in-law, John Hay ($3,000). The first academic building was the gift of Anna M. Harkness, who also donated Harkness Chapel to honor the memory of her daughter Florence. Flora donated $75,000 for the first dormitory, named for Linda Thayer Guilford, and in 1891, she gave another $75,000, most of which was to go into an endowment for the college. The Cleveland Plain Dealer called this “ A Princely Gift. ”[46] In 1901, she donated, (not very) anonymously, the funds for Haydn Hall, a classroom building. She also gave small gifts “from books to … boating permits [,] … making it possible for the young women of the college to enjoy healthful exercise by rowing on the pond in Wade Park.” [47] She and Samuel in 1898 gave $12,000 to the university library. [48]

Adelbert Stone had gone to Yale, but higher education did not figue into Amasa Stone’s plans for his daughters. They might have attended Mount Holyoke College, for example, where Guilford had gone, or to nearby Oberlin College. Instead, Clara married John Hay when she was 24. Flora devoted the decade between her high school graduation and marriage to her temperance and day nursery work.

The College for Women gave Flora her long-delayed chance to go to college. Even though she was a wife and the mother of four young children, with a demanding social and civic life, she visited the college almost every day, getting to know the students and bringing gifts or visiting lecturers. She invited the graduating class to her home every spring. [49] And sometimes as a guest, sometimes as a hostess, she, and often Samuel, attended formal parties, dances, and receptions at the college. She also served on its Advisory Committee.

In 1907, she and Clara donated a chapel to Adelbert College, a memorial to their father’s memory and a commemoration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the college’s move to Cleveland that he had engineered. Amasa Stone Chapel was completed in 1911, two years after Flora’s death.

On January 21, 1909, students from both the College for Women and Adelbert College lined Euclid Avenue to pay tribute to Flora as her funeral procession passed the campus on its way to Lakeview Cemetery. Although during her lifetime, she did not permit the name change, in 1931, the College for Women became Flora Stone Mather College, acknowledging her gifts of time, energy, and money. (She had also rejected the suggestion that Hathaway Brown School, another beneficiary of her generosity, be named after her.[50])

Amasa Stone had built a high school for his daughters, the Cleveland Academy, and a college named after his son Adelbert. Flora (and Samuel) not only gave generously to Adelbert College but helped to assure the survival of the controversial young college for women. Adelbert and Flora Stone Mather Colleges, perhaps the only coordinate colleges in the country named after siblings, were consolidated in 1971, along with Cleveland College. The three were renamed Western Reserve College in 1973 after the merger with Case Institute of Technology that produced Case Western Reserve University. [51] Flora’s name lives on in the Flora Stone Mather Center for Women at the university, which provides services and advocacy for women students and faculty.

After her death, Samuel – who himself had missed out on college – continued her tradition of giving to the university. He and his children gave the Flora Stone Mather Memorial Building in 1914, and in 1930, a $500,000 addition to the building. [52] Samuel also donated $400,000 to the university in 1923 and made gifts to various programs within the university. [53]

Like her father, Flora donated to Lakeside Hospital, originally the Protestant Home for Friendless Strangers, during her life and at her death. [54] Samuel was also a major benefactor of the hospital, instrumental in its move to University Circle and serving as president and chairman of its board of trustees from 1899 to 1931. Mather Pavilion honors his memory. [55]

Other women have also given generously to Cleveland. Among them are Frances Payne Bolton and Elizabeth Severance Allen Prentiss. Like Flora, both women inherited and married money, and both became important public figures.

Prentiss (1865-1944) was the daughter of Louis H. Severance. Her first husband, Dr. Dudley P. Allen, was on the faculty of the Western Reserve University Medical School; he died in 1915. She married industrialist Francis F. Prentiss in 1917. She donated the Allen Memorial Medical Library to Case Western Reserve University, made significant gifts to the Cleveland Museum of Art, and established the Elizabeth Severance Prentiss Foundation to promote medical research. In 1928, she also became the first woman to receive the Chamber of Commerce distinguished service medal. [56]

Bolton (1885-1977) was the daughter of banker-industrialist Charles W. Payne. Volunteer work with the Visiting Nurse Association in New York City inspired her interest in professional nursing, and she funded a school of nursing at Western Reserve University in 1923. This was named the Frances P. Bolton School of Nursing in 1935. In 1939, she finished the unexpired term in the U.S. House of Representatives of her late husband Chester Castle Bolton and held that office until 1968. [57]

Yet Flora stands out because of the breadth and depth of her commitment to the city and its people. She would be thrilled that her husband was named Cleveland’s “first citizen” for his role as founder and funder of its Community Chest, the forerunner of United Appeal, as well as for his leadership of many other organizations.[58] She would likely be embarrassed that in 2010, she and Samuel were named the second most influential people in the city’s history: their generous partnership has sustained Goodrich House, Western Reserve University, University Hospitals, and countless other significant institutions. [59]

Always the modest daughter, she properly acknowledged her debts to her heavenly and earthly fathers. Nevertheless, Flora became her own woman, creating a new path and new opportunities for herself and others.

[1] Quoted in Gladys Haddad, Flora Stone Mather: Daughter of Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue and Ohio’s Western Reserve (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2007), xi. I am deeply indebted to this sensitive portrait of Flora’s private life as daughter, wife, and mother. I have focused instead on her public life. I also want to apologize for referring to Flora Stone Mather by her first name, which I would never do if she were present. However, since her name changes from Flora Stone to Flora Stone Mather after her marriage in 1881, it seems easier – if somewhat disrespectful – to use “Flora” throughout this essay.

[2] Haddad, xi, 70.

[3] Quoted in Haddad, 10.

[4] Quoted in Haddad, 54.

[5] Haddad, 20.

[6] Haddad, vii, viii, 38-39.

[7] David V. Van Tassel and John G. Grabowski, Dictionary of Cleveland Biography (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1996), 309-10.

[8] C.H. Cramer, Case Western Reserve: A History of the University, 1826-1976 (Boston: Little, Brown & Company), 81-86.

[9] Haddad, 70-71.

[10] Haddad, 108-9.

[11] Michael J. McTighe, A Measure of Success: Protestants and Public Culture in Antebellum Cleveland (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 29.

[12] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 17, 1863: 3.

[13] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 28, 1866:3.

[14] In October, 1879, the great evangelists Dwight L. Moody and Ira D. Sankey preached to full houses at Old Stone; one sermon was on “The Work and Power of the Holy Spirit.”Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 9, 1879: 1; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 10, 1879: 4.

[15] Jeannette Tuve, Old Stone Church: In the Heart of the City Since 1820 (Virginia Beach, Virginia: Donning Company, 1994), 42.

[16] Marian J. Morton, “Temperance, Benevolence, and the City: The Cleveland Non-Partisan Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1874-1900,” Ohio History, Vol. 91, Annual 1982: 58-73.

[17] Cleveland Day Nursery Association, Mss. 3667, container l, folder 14, Western Reserve Historical Society (WRHS), Cleveland, Ohio. The temperance movement’s ultimate success, the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919, was opposed by Samuel Mather when in 1928, he joined the board of the Association against the Prohibition Amendment: Kathryn L. Makley, Samuel Mather: First Citizen of Cleveland (Minneapolis: Kathryn L. Makley, 2013), 46

[18] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27, 1876: 4.

[19] Mss. 3677, container 1, folder 14, WRHS.

[20] Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 18, 1880: 4.

[21] Quoted in Haddad, 31.

[22] Haddad, 75.

[23] Mss. 3667, container 1, folder 3, WRHS.

[24] Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 30, 1887: 2.

[25] Goodrich House, Mss.3505, container 5, folder 2, WRHS.

[26] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 7, 1897: 6.

[27] Mather Family Papers, Mss. 3735, container 8, folder 7, WRHS.

[28] Frederic C. Howe, Confessions of a Reformer (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1988), 76.

[29] John G. Grabowski, “Social Reform and Philanthropic Order in Cleveland, 1896-1920,” http://www.teachingcleveland.org.

[30] Mather Family Papers, Mss. 3735, container 8, folder 7, WRHS.

[31] Mss. 3735, container 8, folder l, WRHS.

[32] Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 18, 1900: 1.

[33] Marian J. Morton, Women in Cleveland: An Illustrated History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana State University Press, 1995), 42-43.

[34] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 7, 1905: 33.

[35] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 11, 1901: 10.

[36] Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1905: 6.

[37] Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1904: 12.

[38] Consumers League of Ohio, Mss 4933, container 1, folder 26, WRHS.

[39] Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 13, 1905: 4.

[40] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 5, 1908: 7.

[41] C.H. Cramer, Case Western Reserve: A History of the University, 1826-1976 (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1976), 78-86.

[42] Cramer, 85.

[43] Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 3, 1889: 8.

[44] Cramer, 89-98.

[45] Cramer, 100-102.

[46] Cramer, 102; Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 23, 1891:8.

[47] Cramer, 103.

[48] Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 20, 1898: 5.

[49] Cramer, 103.

[50] Haddad, 87.

[51] Richard E. Baznik, Beyond the Fence: A Social History of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University, 2014), 355.

[52] Haddad, 109.

[53] Baznik, 86.

[54] Haddad, 79-80, 108.

[55] David D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 1034.

[56] Van Tassel and Grabowski, Dictionary of Cleveland Biography (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 359.

[57] Van Tassel and Grabowski, Dictionary, 53.

[58] Makley, 25.

[59] Plain Dealer, December 26, 2010: H2.

The Passing of a Giant: Lou Stokes by Mansfield Frazier in Cool Cleveland July 2015

The Passing of a Giant: Lou Stokes by Mansfield Frazier in Cool Cleveland July 2015. The original link is here

MANSFIELD: The Passing of a Giant

The passing of Congressman Lou Stokes not only brings down the curtain on one of the most accomplished lives in the history of American politics, it also brings an end to us having a direct link to the most activist period of the struggle for black rights and empowerment in this country. The Congressman’s attainments in life stand as a towering testament to what can be achieved via enlightened, determined — nay, fierce — efforts by a public official to turn America into the country we profess to be, but always seem to fall far short of in reality.

If there are still battles for blacks to fight in America — and there certainly are — there are less of them due to the victories Lou Stokes won with his keen intellect, superior upbringing and tenacious spirit. But the congressman, ever the keen student of history, sometimes would point out that he didn’t fight alone, or even initiate the local struggle for blacks’ full equality in this experiment in democracy we call the United States of America. It began long before he took on the mantel of leadership, but he knew he was the beneficiary of former political struggles and carried the battle flag forward proudly.

Just as Birmingham, Ala., is known as the birthplace of the black civil rights movement, Cleveland can rightly claim to be the birthplace of the black economic and political rights movement in this country, in large part due to the efforts of men and women like John O. Holly, Charlie Carr, Marge Robinson, Isabelle Shaw, William O. Walker and a whole host of others.

In 1935, at age 32, Holly would become the driving force in establishing the Future Outlook League, which grew to become one of the most powerful organizations in Cleveland demanding — and achieving — better economic treatment for blacks. It was a long and rocky road he had to travel to win victories in the end, but the hallmark of his journey was his tenacious perseverance and determination: When something got in his way, he found a way around, over or though it. He had a tremendous sense of vision, and better yet, the ability to transmit what he could envision to others. If there is such a thing as a natural-born leader, he fit that description to a T, and both Lou and Carl Stokes frequently acknowledged Holly’s commitment to the cause, and the debt they — and others — owed him for paving the way. In fact, Carl Stokes once served as Holly’s driver.

Holly passed the leadership mantel on to Charlie Carr, who was destined to become — arguably — the most politically powerful black man in Cleveland. He certainly was the most skillful and clever, if not always the most liked. The joke was, Carr was always the smartest man in the room, and if someone didn’t realize it, he had no problem letting them know. He’d won his seat from Republican W.O. Walker, then the publisher of the Call & Post, on his third attempt, by making a campaign promise to introduce legislation that would make it virtually impossible for the police to raid and arrest numbers operators. His argument was simple: If Catholic churches could host bingo games and casino nights, why then couldn’t blacks play the numbers without fear of arrest? It was this kind of clarity of thought, pointing out disparities of treatment, that’s defining police/black community relations to this very day. Carr was way ahead of his time.

Before his death, Arnold Pinkney, who was a key advisor to both of the Stokes brothers, stated that neither of their victories would have been possible without the advice of Charlie Carr. “After we won, black politicians from all over the country came to Cleveland to learn how we’d pulled it off. We’d take them to talk to Carl and Lou, and then to talk to Charlie. They’d sit at his feet, and they’d listen, and they’d learn how to win,” said Pinkney.

So, Congressman Lou Stokes’ great accomplishments and sterling legacy was but a continuation of a long line of astute political leadership that was passed down to him by others; men and women that would be exceeding pleased and proud in regards to what he did with what they bequeath to him. He took the movement for black rights — indeed the rights for all Americans — further than any of his political ancestors could have possibly imaged. He truly shall be missed, and the likes of him will never pass this way again.

Nonetheless, the struggle continues.

Squire Sanders and the Sabotage of Cleveland by Roldo Bartimole Written June, 2009

SQUIRE-SANDERS AND THE SABOTAGE OF CLEVELAND

written June 2009

By Roldo Bartimole

This is a story of civic sabotage.

The desire for the private sector to damage, destroy and take over the Cleveland’s public electric power system reveals an important lesson in how power works in this or any community.

It also is instructive in the sense that you can apply these past lessons to today’s events and Squire-Sanders’s role in the medical mart.

This piece continues my attempt to review aspects of power that have been used in the community and to suggest how it is used today.

Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, Cleveland’s second largest law firm at the time, was a key player in this assault on public government.

Oddly, Squire-Sanders represented the city at the same it represented CEI, the private electric company. Guess whether the city or CEI got the best representation. The city claimed in court papers that the flow of crucial financial information went one way – to CEI, never to the city.

A lot of information about this situation became publicly available because the city eventually sued CEI. Court cases open private matters to public scrutiny.

Here’s the issue. Back in 1972 the city needed financing to help improve its electricity system. It wanted to borrow $9.8 million by letting bonds. Squire-Sanders served as its bond counsel.

The original legislation provided for sale through the City’s Sinking fund. If this didn’t work the city wanted to borrow via its own treasury account. This would allow the city to borrow from itself and at cheaper rates than on the private market.

However, an amendment to the city’s legislation, written by a Squire-Sanders attorney, stated that the bond issue could only be made on the open market. The amendment was attached to the legislation by then Council utilities chairman Frank Gaul, a close friend to CEI. Gaul in a court deposition admitted that he took gifts from CEI general counsel Lee Howley, a former city law director, and cooperated with the company in other ways.

Another Squire-Sanders lawyer wrote the original city legislation. It wanted the borrowing to avoid the private market.

“At that meeting the SS&D lawyer who wrote the ordinance was asked by the (city) law director to defend it, but, says the city, he “declined to defend his own work product and CEI’s crippling amendment was adopted and the amendment was approved…” I wrote from city documents at the time.

The move delayed the required borrowing for improvements until 1975. Just CEI’s desire. Ironically, the delayed bond issue was made through the city’s treasury account, as originally planned.

On another occasion during this period, the city attempted to buy backup power to avoid bad service. A CEI memo revealed that its executives, along with a Squire-Sanders partner, decided “The the company should refuse” to allow the city’s system to join a group that would give Muny Light cheaper power it vitally needed.

The city claimed that Squire-Sanders lawyers’ “representation of the city has endured so long, involved so many of its lawyers, and been so all pervasive it is very difficult to put any limits on their knowledge of the city’s affairs… Their inside knowledge… very likely exceeds that of the city itself.” All too true. Sabotage.

One of the milder charges against the law firm at the time was, “It would appear that Squire-Sanders used the management and financial information gleaned from its representation of the city for the benefit of CEI,” according to a brief that asked that Squire-Sanders be disqualified from representing CEI before the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission on an issue involving the city. Sabotage.

Here were some of the charges the city made against the law firm:

– It allowed amendments to legislation that it wrote to insure the city wouldn’t get needed financing.

– Advised CEI of a plan by which it could thwart the city’s attempt to get interconnections to needed electric power, although the law firm knew that the plan was likely illegal.

– Participated in CEI decisions that denied Muny Light cheaper power source.

Squire-Sanders, as today, injects itself into public matters. Indeed, it is used by many politicians as consultants. This puts the law firm in a central position on many public decisions, as Nance has been with the Browns situation and now the Medical Mart/Convention Center project.

One of the strategies businesses uses is to offer itself as helpmates to the city.

This was the case in 1967 when Ralph Besse, chairman of CEI, and a former Squire-Sanders law partner (upon retirement he went back to the law firm as a partner), formed the Inner City Action Committee to supposedly “help” Mayor Ralph Locher. The city was in serious trouble at the time with its urban renewal program.

Instead of helping, Besse administered a severe blow to Locher in a re-election year. First, he tried to foist one of his people on Locher to head the city’s urban renewal program. His odd choice was a former major general of the U. S. Army.

Locher balked. Besse turned on Locher. He went to the always accommodated Plain Dealer. The Pee Dee, as I have always liked to call the paper, did more than simply accommodate. It ran a top of Page One headline: “Besse’s Inner-City Group Quits Locher.” It was a powerful blow to a beleaguered Locher. Sabotage.

Locher did hit back. “I have not yet seen on real constructive action taken by the committee. So far we have heard some cries from them and they have made some demands on us. Where’s their action?” Locher’s point had validity.

Besse, of course, had an ulterior motive in embarrassing the mayor. His company wanted control of the city’s municipal light plant. But that never came into the public discussion. The media rarely, if ever, call corporate people on their self-interest in civic matters.

These efforts poisoned the relations between government and the private sector as dominated by corporate/legal interests in Cleveland.

This is an important point. These efforts damaged decision-making and leadership in this town. They built mistrust into all civic dealings.

Besse greatly admired favored Hitler general Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. He admired Rommel so much that he ordered his top executives to read him and adopt his methods.

War, not business.

One of his lines to his executives read, “The dead are lucky, it’s all over for them.” He had just finished reading ‘The Rommel Papers,” edited by B. H. Liddel Hart.

“There are so many places (in the book) where the parallel with business command is apparent that I have copied a few of the most interesting quotations… and have attached them,” wrote Besse to his executives.

One employee challenged him and he was dumped. He charged Besse wanted the company to operate as a war machine even though the company was actually a public utility with a “guaranteed profit.” I think this truth about it being a public utility whose profit was assured goes to the core of why CEI and the business community so wanted Muny out of the way. (See the full story in Point of View, Vol. 10, No. 22, May 22, 1978.)

The truth was both the city’s plant and CEI were not businesses in the true sense.

Here is one of the passages he cited for his executives:

“If there is anyone in a key position who appears to be expending less than the energy that could be properly be demanded of him, or who has no natural sense for practical problems of organization, then that man must be RUTHLESSLY REMOVED.” (My emphasis).

The fight by the city to maintain its electric system is a classic case of public vs. private interests. It should be studied in business economics classes. It goes to the core of many ideological problems being examined now on the national stage.

We will see how CEI and Squire-Sanders tried to destroy the city’s electric system over a number of years and how it was caught breaking the law by the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and how a federal lawsuit, in two trials, failed because of a Cleveland judge’s bias permeated the courtroom.

The Paradox of Progress in Tremont, Ohio By Dawn Ellis

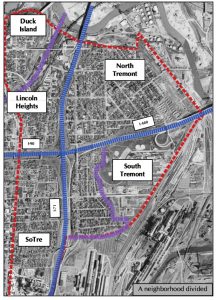

map courtesy Tremont West Dev.

The Paradox of Progress in Tremont, Ohio

By Dawn Ellis

What does progress look like and how is it measured? What is gained and what is lost in the name of progress? For the city of Tremont, Ohio, for decades, progress was defined through the destruction of neighborhoods, social capital and community cohesion. Long-term Cuyahoga County Engineer Albert Porter envisioned progress in terms of rapid, individual automobile transport from the Central Business District to the suburbs. During his almost 30-year tenure (1947 to 1976) he would oppose a city subway plan and endorse and establish most of the current highway system linking Cleveland to the suburbs. To encourage the supposed good of increased access to the Central Business District of Cleveland from the outlying suburbs through the construction of highways, Tremont was eventually carved into 4 quadrants that now attempt to relate to each other as the whole they once represented.

If Tremont will be successful in recapturing the sense of cohesion it previously had remains to be seen, but the question that lingers is: how do we as citizens determine the best use of our land, and how do we value the intangibles such as social capital and collective memory against financial and economic gain?

The Tremont area, 3.3 square miles bounded roughly by the Cuyahoga River to the east and north, West 25th Street to the west and the Harvard Denison Viaduct and Riverside Cemetery to the south, was settled in 1818 by Seth Branch and Martin Kellogg, from New England. It began as more of a colony within the city of Ohio City but would eventually merge with Cleveland in 1854. The area grew slowly. The Reverend Asa Mahan (then president of Oberlin) envisioned Tremont’s acres as a cultural center not only for Cleveland, but all of Ohio. Reverend Mahan, with landowners Seth Branch, Martin Kellogg, H.R. Hadlow, Hiram Aikens and Brewster Pelton, moved forward with a plan to establish a university in the area.

“University Heights” as an idea in 1850 would be laid out with neighborhoods and streets plotted, inspired by the vision of bucolic serenity and high culture. University, Professor and College were some of the first plotted street (these streets still exist in Tremont), names chosen to reflect the educational and cultural aspirations of the settlement. The university idea would eventually fail but University Heights became an exclusive residential area with impressive historic architecture whose Franklin Avenue rivaled the famous Euclid Avenue on Cleveland’s east side.

The War of 1812 had helped establish Cleveland as a trade center and by the 1820s the port was a successful commercial hub. In 1832 the Ohio and Erie Canal, of which Cleveland served as the terminus, was completed and some of the commercial promise of the lake was realized. By 1849 with the completion of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland’s prosperity and growth were intimately tied to transportation, first through the canal, then through the railroads, and finally through the automobile industry.

The Civil War period proved immensely transformative for Cleveland. By 1860 there were five railroad lines that ran in and out of the city; it was well positioned to profit from the trade in raw materials and other goods. At the turn of the century Cleveland’s important industries of iron, steel and oil refining played a part in the city’s entry into the emerging automobile industry. Its combination of access to raw materials, a burgeoning manufacturing base and a solid class of well-to-do consumers helped make Cleveland a leading automobile city in the United States. Spurred by the work of such people as Alexander Winton, who introduced his first car to Cleveland in 1896, the automotive and automotive parts industry played a large role in the commercial development of Cleveland. Automakers such as Winton, Peerless and Baker Electric helped solidify the importance of the automobile in northeast Ohio and Cleveland.

Over the years Tremont’s upper scale residential atmosphere gave way to the development of such industries as steel making and oil refining that led to an influx of immigrant workers to the area and an exodus of the New England families that had settled the land, who continued to move south and west, towards suburbs like Parma. One of the earliest industrial establishments, the Lamsom-Sessions Company, a bolt manufacturer in 1869, helped lure a diverse population to this part of Cleveland. Towards the second half of the 1800s, parcels in Tremont were among the most affordable in the area and working class families were able to purchase homes, or land on which to build homes, that were near their places of employment; visions and plans of grand estates and gardens gave way to working class residential and industrial neighborhoods.

New immigrants could establish veritable ethnic enclaves within Tremont; families could live, work, worship and shop among fellow immigrants. Among the first of these immigrant groups to settle in Tremont were the Germans and Irish, who concentrated themselves in the lowlands. German and Irish were followed by Polish, Greek, Ukrainians and Puerto Ricans-more than thirty nationality groups have lived in Tremont over the years. The legacy of these different groups can still be found in the architecture of the housing that reflects a variety of styles such as Victorian and Queen Anne.

Unfortunately the ethnic and class cohesion that Tremont experienced did not protect it from the suburban drain that began to empty the urban areas across the country by the 1930s. Despite the grandeur of Franklin Avenue and its impressive churches, Tremont was not an overall affluent section of Cleveland. The conditions of working class industrial regions were sometimes poor and the economic devastation of the Depression hit working class communities like Tremont especially hard. Some homes had no running water well into the 1950s, and houses built for single family occupancy served twice as many people as intended.

Congestion and poverty were rampant, and by 1939-40 Tremont was slated for governmental intervention in the form of a public housing development known as Valley View Homes. This is the map of the location of the development.

This project was seen at the time as a public service and residents were generally receptive to this sort of governmental program. The plight of the 250 families that were displaced as a result of this project foreshadowed what would transpire repeatedly in Tremont.

As property values fell and population numbers decreased throughout the 1950s, Tremont become a prime candidate for the urban renewal projects (often designed to facilitate the flow of vehicular traffic in and out of the Central Business Districts of cities) that spread over the nation that combined the construction of highways and housing developments with mass razing and resident relocation in an effort to combat slums and urban blight. Financially able residents had been leaving the area for southern suburbs since the late 1800s, yet at that time, more people were entering than leaving Tremont and the population continued to rise until its peak of 36,686 residents in 1920.

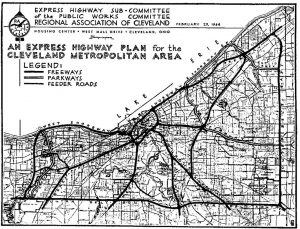

Cleveland’s Freeway Plan of 1944 (that followed an earlier plan proposed in 1940) was designed as a multimillion dollar integrated freeway system to relieve downtown congestion.

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland’s overall urban renewal plan was the largest in the United States and targeted more than 6,000 acres east of the Cuyahoga River in the inner city. By 1966 the Department of Housing and Urban Development had authorized assistance for seven urban renewal projects in Cleveland: Longwood, St. Vincent’s Center, Garden Valley, East Woodland, Erieview 1, University-Euclid 1 and Gladstone, that represented a mixture of rehabilitation, clearance and redevelopment for residential and commercial use.

Cleveland’s General Plan of 1949 under the City Planning Commission of Chairman Ernest Bohn and Director John T. Howard, provided a framework for what was intended to be a redevelopment of the city. The Plan focused on “protection, conservation and redevelopment…aimed at establishing good living standards for every home neighborhood in our city and making decent housing available for all families at prices and rents they can afford to pay”. A critical component of this plan would be slum clearance and it was estimated that 13,000 Clevelanders would have to be relocated from lands and neighborhoods.

Through the Housing Act of 1949 the city was authorized to purchase property in designated blighted areas in order to clear it and sell it to private developers at a reduced price, with the federal government absorbing much of the true cost of the project. The overall intention of the program was to spur construction of improved low-income, public housing in targeted areas, Unfortunately newly constructed housing units never numerically equaled the destroyed units and urban cores struggled to entice people back to the inner city.

Bolstered by the 1954 Berman v. Parker decision of the Supreme Court that expanded the scope of eminent domain (the power of the government to take private property in return for reasonable compensation) and its applicability in urban renewal projects, planners and housing reformers had a powerful tool with which to reshape American cities and society. As planners correlated blighted neighborhoods with public nuisance, and condemnation and re-development with the public good, it became easier to justify private property seizures in increasing numbers. Once coupled with the incentive provided by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 that provided for a system of 41,000 miles of roadway to be financed through a Highway Trust Fund (developed through the excise tax on fuel and tires), the partnership between urban renewal and highway construction became solid.

In the early 1960s Tremont was one of eight targeted neighborhoods in Cleveland for the neighborhood Improvement Program that had developed from the City’s Workable Program of the late 1950s. These programs were designed to control the spread of blight and slums. Blighted parcels and slum neighborhoods could be defined by states of deterioration, age and obsolescence, inadequate provision for ventilation or open spaces, unsafe and unsanitary conditions, overcrowding of buildings on the land and excessive dwelling unit density.

Tremont, through its age, primary population and historic function, fell into this definition of a blighted neighborhood and its voluntary participation in the Workable Program signaled its willingness to authorize a certain amount of clearance and redevelopment as was intended by the program.

Howard Whipple Green’s census of 1954 revealed that 87 to 100 percent of the housing stock in 8 of the 9 tracts that comprised Tremont was built before 1920 and that no new housing was being built. In 1960 the 8459 housing units in Tremont included more than 300 “miscellaneous” dwellings that were often shacks or conversions.

Neighborhood destruction in Tremont for freeways began with the Innerbelt Bridge at Abbey Avenue and West 14th Street in 1941. Unlike their southern neighbors of Brook Park (who unsuccessfully resisted the planned path of the freeway), Tremont did not wage a sustained campaign against the Medina Freeway (I-71). The residents seemed to belong to several schools of thought: one group was ready to leave and willing to accept any fair price for their property to sell it, they were ready to leave the crime, congestion and pollution of the neighborhood and perhaps move further south into cleaner, less dense suburbs such as Parma.

Another group was nervous about the change but did not want to stand in the way of “progress” and a third group, made up of the poorest of Tremonters would see their lives torn apart as their neighbors left and the businesses they had frequented for years closed. Residences with several generations were split up as they did not receive enough money to buy new houses to accommodate their family size. The sense of community, the familial ties, social capital were all taken from this group.

By the 1970s the massive slum clearance and forced relocation approach to urban renewal was becoming less popular with governments and the public. Revolts in such cities as San Francisco, New Orleans and Shaker Heights, Ohio had successfully fought against interstates plans in their areas. Highway construction enthusiasts like Albert Porter’s highway vision would not extend to Shaker Heights and this defeat signaled the coming decline of the supremacy of this urban planning phase.

The Tremont area’s historic importance lies in its being one of the oldest and most densely built neighborhoods in Cleveland- the very qualities that are compromised by large scale land clearance. Its settlement also reflects the broader national pattern of industrial progress and immigration. Tremont was the site of the largest of Cleveland’s seven Civil War camps, Camp Cleveland, and it is included as part of the Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor.

Tremont is also listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is a local landmark as proof of its representation of a pivotal period in U.S. history. The architectural richness of the residences that reflect several styles and the historically ethnic church stock (including landmarks such as the United German Evangelical Protestant Church, the Holy Ghost Byzantine Catholic Church and St. Theodosius) are important visual links to the development and history of Cleveland.

The crusade of using highway construction as a tool in the scheme of progress known as urban renewal and slum removal has lost some of its moral urgency and authority, but there still remains the thought that improvement for economically challenged neighborhoods consists in highway construction and resident displacement. Whether Tremont’s history will influence future decisions on the unintended costs that come with this sort of progress remains to be seen. Perhaps the story of Tremont will come to mind as we debate the merits of such projects as Opportunity Corridor and consider the value of people space versus car space, and investigate how much of our land should be dedicated to going somewhere instead of being somewhere.

“Heart of Steel” Series from Plain Dealer About Steel Industry in Cleveland October 2016

Series from Plain Dealer about Steel Industry in Cleveland October, 2016

The Rise of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Belt)

The Rise of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Belt) 2015

Housing Crisis in Northeast Ohio – Where are We in 2015? Video from Forum October 7, 2015

Housing Crisis in Northeast Ohio – Where are We in 2015?

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 7-8:30 p.m.

CWRU Siegal Facility in Beachwood, OH

Panelists:

• Thomas Bier, Senior Fellow, Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University

• James Rokakis, Former Cuyahoga County Treasurer, Cleveland Councilman, Director Thriving Communities Institute

Moderator: Brent Larkin, The Plain Dealer

Northeast Ohio was one of the hardest hit housing markets in the U.S. in recent years. The market has begun to recover, but housing values and real estate taxes remain two of the most important economic issues facing local residents today. This forum will discuss current home prices, new construction, demolitions and foreclosures.

Cosponsored by City Club of Cleveland, Cleveland Jewish News Foundation, CWRU Siegal Lifelong Learning, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland

Here are two news stories from the forum

“Come to Cleveland? Maybe Not” Belt Sept, 2015

Come to Cleveland? Maybe Not” Belt Sept, 2015 by Daniel McGraw