Frank Lausche aggregation

Frances Payne Bolton aggregation

Public Housing / Ernest Bohn aggregation

1 Ernest Bohn from Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

2 Public Housing in Cleveland: A History of Firsts

3 Time and Again from Cleveland Magazine July 2009

4 Robert A. Taft and Public Housing

5 Bohn’s Palisades from “The Cuyahoga” by William Donohue Ellis

6 History of Public Housing in Cleveland from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

WPA in Cleveland aggregation

1 Federal Arts Project from Cleveland Historical

2 Work Projects Administration (WPA) from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

3 Federal Art In Cleveland 1933-43

4 The Cleveland Public Library and the WPA: A Study in Creative Partnership

5 The Works Progress Administration leaves a legacy in Northeast Ohio WKSU Mark Urycki 9/15/2011

Great Lakes Exposition aggregation

John O. Holly aggregation

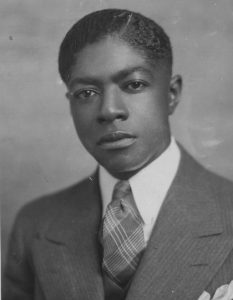

John O Holly 1935 (Cleve Public Library)

1 Cleveland’s Original Black Leader: John O. Holly By Mansfield Frazier

2 Carl Stokes on John O. Holly from “Promises of Power”

3 Future Outlook League from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

4 John O. Holly from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

5 Merchants of Tomorrow: The Other Side of the “Don’t Spend Your Money Where You Can’t Work” Movement