Michael D. Roberts was a reporter for The Plain Dealer in the 1960s and covered many of the events in that decade including the Vietnam War. He later edited Cleveland Magazine for 17 years.

Cleveland in the 1980s

The .pdf of this article is here

While the 1980s gave promise that Northeastern Ohio was reviving, there were historical and contemporary forces at work that would thwart any serious comeback. There was no reversal to the population exodus from the Cleveland. For the first time, the census showed a decline in Cuyahoga County. The biggest problem was a shrinking job market.

The Great Depression of the 1930s is generally regarded as a critical and devastating turning point in Cleveland’s history. By 1980, one could argue that no region in America was so permanently scarred by the Depression than the Cleveland area.

Now, another devastating economic force was descending upon the region. This time it was global in nature and it compounded the damage of the awful economic impact of the Depression. It was the globalization of industry and it was growing at a time when Cleveland was optimistically looking forward to a new decade

To understand the economic gyrations that the region faced in the 1980s, one has to reflect on the turn of the 20th century when Cleveland found itself on the cutting edge of what is known as the Second Industrial Revolution. An entrepreneurial spirit flourished here as rarely seen in America.

In the early 1900s a diverse economy was emerging in the city as inventors and investors found their places in steel, machine tools, electricity, paint, automobiles, shipping and manufacturing. Entrepreneurs were attracted to the city and were welcomed by fellow inventors and industrialists.

Seventy fledging automobile companies were located in Cleveland. Alexander G. Winton made the first commercial auto sales in the country here.

Technological spinoffs created new businesses at an astounding rate. For instance, the Brush Electric Company, founded in 1880, was directly responsible for the establishment of such blue chip companies as Union Carbide, Lincoln Electric, and Reliant Electric simply through the technological transfer of former employees.

Key to the success of these aspiring enterprises was the ability to attract financial capital through which they could develop and market their innovations. The need for capital, in turn, created financial institutions attuned to the spirit of enterprise that permeated the community.

At one time, prior to the Depression, the city hosted 38 banks and a stock market that carried more relative industrial stocks than its much larger counterpart in New York.

Cleveland inventors were among the top producers of patents in the country, resulting in the creation of many small businesses which thrived because of the local financial markets. It was the maturity of these companies that created the wealth that drove Cleveland.

The Depression destroyed many of the city’s financial institutions and with their demise went the availability of capital. The small, entrepreneurial business that had spun off the innovation that created great companies withered and died.

When the country recovered, the financial markets of the East Coast came to dominate. Even into the 1980s local business innovators complained in a common refrain that Cleveland banks were too conservative. The memory of the Depression lingered indelibly in bank ledgers.

Years later a senior partner at Baker Hostetler, one of the city’s prestigious law firms, would explain that the reason the firm originally opened offices in other cities was to keep their wealthy clients who fled the city in the wake of the Depression.

The loss of a vibrant financial market cost the city’s economy the self reliance that had attracted so much innovation and success in the past. The city’s business culture changed from spirited entrepreneurs to conservative bureaucrats who shunned the risk that created wealth and who merely managed the large companies that had survived the Depression.

The other factor that had a long- range effect upon the region was its reliance on manufacturing jobs with limited knowledge requirements, but decent pay. This work did not need to be supported by higher education

World War II and the Korean War helped revive the regional economy, but postwar global forces were already at work that would be as powerful in its negative impact as the Depression. In fact, it could be argued that the Depression rendered the region unable to cope with the global events a half century later.

The global economy began with the recovery of foreign nations from World War II and the emergence of cheap labor and a new wave of technology. It was most evident in the 1970s as foreign automobiles, the Japanese being most prevalent, began to challenge American manufacturers.

By 1980, with the vast federal highway system completed in the region and school busing an emotional city issue, the suburbs held more allure than urban life for those who could afford it. The population in Cleveland dropped 177,000 in the last decade to 573, 822. Worse yet, Cuyahoga County experienced its first decline since 1810 with a 12.9% decrease to 1,498,400.

The loss was not all in the city. Parma, once the largest suburb in the state, dropped below 100,000, losing 7.7% of its population in the last decade.

Even the most casual observer could notice a change in the population shift by simply reading the high school football scores in the newspaper. Schools that had been remote and on the edges of the county were developing better teams, and becoming more competitive with those closer to the city. Schools like Aurora, Avon, Kenston, and others were more and more prominent in the sports news.

Added to the local issues, globalization was making its impact on the way people lived. In retrospect, the post war era in the region had been consumed by issues wrought by parochial politics and the reverberation of civil rights. At first, business and political leadership seemed impervious to the impact of world industrialization on the region.

State and local governments in the region did not react to the new world view because they were neither positioned nor prepared to do so. In Cuyahoga County alone there were 56 different governmental entities, and in reaction to the economic ill fortune they began to offer inducements to businesses in the form of tax cuts.

These inducements were made to attract or maintain companies, but they affected the tax base of communities. These cuts would be a first and inadequate response to the shifting marketplace.

The 1980s brought a new realization that local government had to change to a more regional concept if the area was to make its way in the changing world. The realization that we were no longer competing with an adjoining state, but with vast overseas markets brought with it a need to alter traditional economic and political thought.

While regional or a county government had been proposed, discussed and even put on the ballot in the 1950s, it was not a compelling issue for the ordinary voter. The ethnic nature of politics and the growing emergence of minorities distracted from regional issues.

Yet, economic necessities were forcing certain aspects of regionalism to be implemented. In 1968, the City of Cleveland found itself unable to maintain its port and was forced to merge with the county. Financial and political exigencies created the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District in 1972. The city turned over some of its parks to a regional system when it could no longer afford upkeep. In 1974, the city merged its bus system into the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority.

One regional opportunity that eluded Cleveland was the failure to annex suburbs that wanted to purchase city water. The government in Columbus, Ohio, grew its municipal boundaries by annexing in return for water and thrived.

The unwillingness and the unpreparedness of community leaders to work for a regional government both pre and post World War 2 created a growing economic separation from the rest of the world. It would be a problem that plagued Cleveland and Northeast Ohio into the modern era.

The Northeastern Ohio area could claim the development and manufacture of the automobile since its inception. Generally regarded as the second most important automotive center in the nation, the impact of the global economy began to have a negative impact as imported cars rose in popularity with the American public.

Most noticeable though was the impact of globalization on the steel industry. Following World War II, American companies produced two-thirds of the world’s steel. It was a euphoric time as the industry continued to rely on aging technology to bolster profit margins.

The region’s steel mills were important contributors to this boom, but early in the 1970s it was evident that foreign competitors using new technology and cheaper labor were able to undercut the price of the product.

As double-digit inflation lay waste to the American economy in the early 1980s, adding to the steel industry’s travail, companies merged and unemployment spread. In Ohio in 1975 there were 20 steel companies operating 47 mills. Ten years later only 14 companies operating 23 mills remained. Employment and production had fallen to nearly half of what it had been in the decade before.

Other companies began to be effected by foreign markets and new technology. The venerated Warner & Swasey, one of Cleveland’s oldest companies known for optics and machine tools, was sold in 1980 and slowly dismantled, falling victim to the increasing computerization of industry.

The dwindling steel production saw more job loss in the Great Lakes shipping industry, causing unemployment on boats, on the docks and in related industries.

Having been weaned on manufacturing and heavy industry, the region fell behind in preparation and education for the oncoming knowledge-based technologies. Because universities near Silicon Valley, Boston and Pittsburgh had been the springboard of new technologies, those areas flourished as the 1980s progressed. Cleveland lagged and lost ground.

But there were glimmers of enlightenment in the region. Kent State University began to do research with liquid crystals and Akron University was developing polymers which hopefully would replace a decimated rubber industry in that part of the region. The Cleveland Clinic was growing faster, on its way to becoming not only a preeminent hospital, but a place of medical discovery.

Cleveland State University, late in coming on line, was nevertheless growing and beginning to have an impact on the community. Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University, which had merged in 1967, was trying to create a new identity to meet the challenges of a new world. The truth was that the region had failed to devote the needed resources to higher education decades before and was now in a race to catch up with the rest of the world.

Thus, the global economy had a far-reaching effect on the daily lives in Northeast Ohio at almost every level. Things would never be the same.

By 1980, Cleveland was exhausted and nearly inert from the political and racial turmoil that seemed to taint every issue that touched its citizens. It was so pervasive that during a political meeting on the East Side, an elderly black man leaned over to City Council President George Forbes and asked in all earnestness why no one could get along downtown.

The remark had a profound influence upon Forbes. It signaled that even the proverbial man in the street was sick and tired of a city hall that was a national joke and lacked the capability to staunch an ever increasing flow of population and business away from the city.

It also signaled how far the region was behind the rest of the global village.

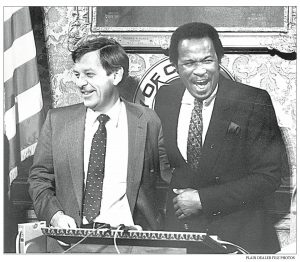

The next decade in Cleveland would feature leadership that would attempt to bring order to the town. Forbes was destined to be the most dominant figure. Outspoken and audacious, he had two agendas: helping blacks attain a respectable place in Cleveland society and making the city a better place for all. He could not achieve one without the other.

Together with Mayor George Voinovich, Forbes formed a leadership tandem that elevated the city from its chaos and engendered cooperation with the business community that had not been seen in years.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, Forbes came here in 1950 after serving in the Marine Corps to attend Baldwin-Wallace College with the idea of becoming a minister. In time, his ambitions changed and in 1963, he was elected to the Cleveland City Council just as the civil rights movement was gaining traction.

By the 1970s, Forbes had become the most powerful black politician, following Carl Stokes’ tenure as mayor and his move to New York to become a television anchorman. Forbes was elected council president in 1973 and remained in that position throughout the 1980s.

After the tumult of the 1970s, the city needed a respite, and there was a sense of resignation on the part of the political and business leadership that in order for the city to have a future there needed to be more understanding and cooperation.

Only strong leadership could manage such a course through the no man’s land of tangled politics and civic malaise that was cast over the city as if a storm had passed through and left a wake of frustration.

Complementing Forbes was George Voinovich, elected mayor in 1980 who now was a seasoned public official, having served as a state representative, county auditor, county commissioner and lieutenant governor. Voinovich had the confidence of the business community and possessed a fiscal sensibility that gave city government a course of direction that it had not seen in a decade.

At first, Voinovich was leery of Forbes. By nature, Voinovich was conservative, quiet in his ways and not given to displays of emotion. The fact that he had the most successful political career of any mayor since Frank J. Lausche in 1944 testifies to his planning and patience. He was a man navigating a mine field when it came to his political career, careful with each step.

Conversely, Forbes was a man of action who paid little attention to the consequences. As city council president, he tolerated little deviation from his colleagues, fought frequently with the media and trumped with race-card politics. His radio talk show on WERE was regarded as outrageous, especially on the West Side where his humorous references to race were not taken lightly.

If Voinovich tip-toed around controversial political issues, Forbes rushed through them like a rampaging bull. Together they made for interesting and effective leadership, something the city had not seen since the early Stokes administration

Forbes had many admirers in the business community, especially James Davis, the managing partner of the powerful law firm Squires, Sanders & Dempsey. It was Davis who put the full weight of the firm behind Forbes when he was indicted on eleven counts for accepting a kickback from a traveling carnival. Davis rallied the business community to support Forbes, who was ultimately found innocent.

Davis acted as a mentor to the council president, instructing him in the ways of business, pointing out that government does not create jobs, but creates an environment where business can thrive and create jobs.

Something that was clearly not thriving as the decade opened was the Cleveland Press, the afternoon newspaper that had meant so much to the city for most of the century, at times acting as its very soul. Time and circumstance had slowly sapped the strength from the paper. Television and an expanding highway system that lead from the city was destroying the newspaper. The six o’clock television news made the afternoon edition stale in content and the ever-broadening suburbs made timely delivery harder, limiting the newspaper’s reach to an ever-diminishing audience.

The history of The Press reached back 103 years and it was the flagship of the Scripps-Howard media empire. For 38 of those years The Press had been guided by Louis B. Seltzer, a self-educated man of such drive and vision that his will virtually dominated the city’s life in every way. There was no single person more powerful in the last century in Cleveland.

Seltzer understood the ethnic mix of Cleveland and promoted it through the newspaper. The process built reader confidence to such an extent that its endorsement, or lack thereof, could make or break a politician, project or position.

Regardless of his achievements, Seltzer had his flaws. The coverage of the 1954 Sheppard murder case would be judged by the U.S. Supreme Court as prejudicial to the defendant Sam Sheppard, who would ultimately be acquitted of the murder. Seltzer’s dominance over city hall was so complete that it had weakened the two-party system in a way that would affect politics for years.

Seltzer retired from The Press in 1965, but it was already clear that the newspaper was in decline. The Plain Dealer, for years an anemic competitor, had gained momentum through new management and by virtue of the times. The Plain Dealer staff celebrated the day it surpassed The Press in circulation in 1968.

After Seltzer left, The Press never regained its vitality. It was dutiful and competitive, but there was something troubling about its condition. It was almost like witnessing a friend or relative suffering a long and debilitating illness. It reportedly was losing $6 million annually.

It was no surprise then that in 1980, wealthy industrialist Joe Cole announced he had purchased The Press for $1 million and other considerations. Cole, long active in Democratic politics, intended to revitalize the newspaper and challenge The Plain Dealer.

The Press added color and a Sunday edition and outwardly appeared to be making a run at survival, but behind the scenes Cole was bleeding money at a rate he could not afford. Secretly, he began negotiations with the Newhouse family, owners of The Plain Dealer.

These negotiations resulted in the closing of The Press on June 17, 1982 in a transaction that saw the Newhouses pay Cole some $22.5 million for the subscription list of the Press, and its shopping news.

The circumstances surrounding the closing of the newspaper troubled its former employees and others who complained of antitrust violations. Finally, a federal grand jury was convened to hear testimony, but never returned an indictment,

The death of The Press would have a great impact on the city. The lack of competition would allow The Plain Dealer to lessen the intensity of its reporting over the next decade and in time the city and county would witness government corruption of historic proportion.

The issue of the municipal light plant, which had brought so much woe to the city for so long, still lingered. Voinovich was not about to let it simmer and come back to haunt him politically. Discussions of a possible sale to the Illuminating Company proved unsuccessful.

Finally, the administration confronted the issue by changing the image of what was known as “puny muny”, renaming it Cleveland Public Power and investing in its future. An embittered Illuminating Company countered by moving its headquarters to Akron.

Meanwhile, the embattled school system, under court- ordered busing, floundered from crisis to crisis. The office of superintendent was in a constant state of flux as one after another of the superintendents either failed or found himself in constant conflict with the school board. One superintendent even committed suicide.

The finances were so out of control that one study showed that the politicized custodians were making $1.3 million annually in overtime. The system needed $50 million to repair its buildings and the cost of busing was so expensive that the federal court ordered the state to pay half the cost. Busing did little to improve the academic standards of the system. The majority of students could not pass state proficiency tests.

Enrollment continued to drop, there was flight from the city and citizens finally passed a bond issue to repair schools only to have the school board and superintendent disagree on how the money should be used. The superintendent resigned in frustration. The school system appeared to be in a free fall.

The endless newspaper stories concerning the schools and the lack of quality education in Cleveland’s public system numbed readers, who turned elsewhere to relieve the constant reminder that they were witnessing failure on a massive scale. Sports would become an increasingly popular escape.

To that end, a foretelling meeting took place between George Forbes and a man named Richard Jacobs, a real estate developer who had enjoyed great success, but was little known in Cleveland circles. Jacobs had asked for a meeting with the council president to announce his intention to buy the Cleveland Indians.

The first thing Forbes asked is whether Jacobs could afford to do so. The developer just nodded and Forbes thought the man crazy.

Forbes reached for the phone and called Mayor Voinovich.

“Mayor, you better get down here quick,” Forbes said. I got a man in my office who wants to buy the Cleveland Indians…..Yes, he wants to buy the team with cash. Hurry, I’ll try to keep him here.”

The Cleveland Indians were city hall’s lingering nightmare. Since the 1950s, the team had floundered from one season to the next, cursed by bad luck, low attendance and indifferent ownership. In effect, it had become as much of a charity as any welfare agency in town, being passed from one wealthy family to another, who offered temporary sustenance, but no future.

Rumors that the team would move circulated annually, like a case of flu, and woe to the politicians in office if that was to occur. City Hall lived in fear of that moment. Several real attempts were made to move the team, but were staved off by aggressive newspaper coverage

The appearance of Jacobs would be a beacon of hope in more ways than one. The city had endured so much frustration and disappointment on so many fronts that its citizens had no contemplation of the future. That day in 1986 symbolized the dawning of new hope.

Richard Jacobs was an enigmatic man. Withdrawn, and circumspect to a fault, he was a brilliant businessman who had amassed millions developing shopping centers here and across the country. No one shied from publicity as did Jacobs, so when he bought the Cleveland Indians, his name was as obscure to the public as some of those who played for him.

A native of Akron, Jacobs and his brother, David, had worked hard at building their business and appeared to be diverting somewhat from real estate to dabble in sports, a familiar path taken by men of means who wanted test their fortune in the public arena.

But Jacobs was not your average wealthy man playing at the game. In the beginning, he knew next to nothing about the business of baseball. However, he brought an intensity and financial acumen to the game the likes that had not been seen since the glory days of Bill Veeck in the 1940s.

He also had a keen eye for executive talent which, in turn, assembled a farm system that within a few years would produce a core of players that in the next decade would take the Cleveland Indians to two World Series.

While baseball was the most visible of his pursuits, Jacobs invested in the city in other ways. He purchased Erieview Tower, the orphan left from the aspirations of the ill-fated urban renewal projects of the 1950s, and built a stunning shopping mall on the top of a discarded ice rink called the Galleria.

Later, he announced the construction of a new skyscraper on Public Square that would be known as Society Center which eventually became Key Center. He proposed yet another such building for the Ameritrust Bank on the western side of the square.

Already downtown was booming, aided by tax abatement, with the kind of building that had not been seen since the city’s halcyon pre-Depression days. Sohio cleared the eastern side of Public Square in 1985 and built a 45-story office building that respectfully maintained a lower profile than the Terminal Tower in height.

Forbes and others had urged Sohio to surpass the Cleveland landmark as a symbolic gesture of a new era. Sohio officials wanted to preserve the past and opted to allow the Terminal Tower to be the dominant skyline feature.

Not so Richard Jacobs. As the plans for his tower on Public Square evolved, a reporter asked whether it would be taller than the Terminal. In a rare moment of candor, Jacobs responded:

“You’re damned right.”

Key Center would ultimately rise 888- feet tall, overlooking the Terminal by 180 feet. It was that symbolic split with the past that Forbes had sought from Sohio, a signal of a new kind of spirit in town.

In a sense, Jacobs represented the pre-Depression drive that had fuelled Cleveland’s early growth

That spirit was typified by the building that was taking place downtown. National City Center rose 35 floors on the northwest coroner of East 9th Street and Euclid and opened in 1980. Eaton Center on Superior and East 12th Street was a 28-floor structure that was completed in 1983. Across the street the Charter One Bank building opened its seven stories in 1987.

In 1983, on East 9th Street, the silver, chisel-like structure knows as One Cleveland Center reached 31 stories high, the fifth tallest building in the city at the time.

Ameritech built a 16-story contemporary headquarters on East 9th Street in the Erieview Plaza, the site of the controversial urban renewal project that was planned some thirty years prior.

In 1985, where the old Cleveland Press building stood, a 19-story office building called North Point was built, housing the now international law firm of Jones, Day.

While all of these projects were changing the city’s skyline, its trademark symbol, The Terminal Tower, until 1964 the tallest building in the country outside of New York City, was undergoing a dramatic remake aimed at refocusing Public Square as the heart of Cleveland.

Forest City, a national real estate company founded by the Ratner family here in the 1920s, received $73-million in government loans and aid to convert the Terminal Tower concourse into a vast shopping and business facility now called Tower City Center. The dramatic make over featured some of the nation’s most fashionable stores.

Dick Jacobs’ influence was felt in other ways. His Cleveland Indians played in the dismal confines of Cleveland Municipal Stadium, a cavernous ballpark opened in 1931 that was considered a grand achievement in its time. The stadium was home to the Cleveland Browns as well and operated by the Stadium Corporation, a business entity that leased the facility from the city. Stadium Corporation was run by Art Modell who was the principal owner of the Browns.

Since 1961, when he arrived from New York and bought the Browns, Modell was celebrated as the city’s sports impresario. Outgoing, self deprecating and emotional, Modell carried with him the stigma of having fired one of the best coaches in all of football, Paul Brown, and then never delivering a team that matched the consistency under him.

Shortly after buying the Indians, Jacobs asked Modell to review the lease agreement the team had with Stadium Corporation. The Indians were getting less of the advertising revenues from the signage than the Browns, even though the baseball team played far more games.

Modell refused, and while it was a minor thing it was an ominous omen of things to come. It was clear to Jacobs that he had to have his own stadium if his baseball venture was to be successful.

At one point he asked Modell if the Cleveland Browns were for sale. They were not, replied Modell. Jacobs longed to own a National Football League franchise.

For years there had been talk of building a new stadium or putting a dome on the existing field. The conversation and proposals were aimless, typical of how the city dealt with major municipal projects. But the town was coming to the understanding that if it was going to keep major league sports, something would have to be done about a new stadium or even stadiums.

Other cities were building new stadiums and the baseball commissioner publicly commented that unless Cleveland followed suit there was the distinct possibility of the Indians moving to another town.

In 1984, a proposed increase in property taxes was put on the ballot to finance a domed stadium. Raising property taxes was a political mistake of the first order and opponents had a field day. The issue also was soundly defeated, a signal that the public was reluctant to support the construction of a sports facility at its own expense.

The failure of the tax issue sent Modell a message. In all likelihood, there would be no new stadium in the near future and his best course of action would be to improve the existing structure. The Stadium Corporation was responsible for the upkeep of Municipal Stadium and the money for improvements would have to come from the corporation.

Modell asked the city for a ten-year extension on the stadium lease, expecting quick approval since the city enjoyed a constant stream of revenue from the arrangement. Negotiations lingered for nearly a year before he dropped the proposal, his frustration increasing.

For all of his civic involvement, and it was substantial, Modell never had a true sense of politics. He contributed to campaigns, knew four Presidents, but lacked clout at city hall, possibly because he never really needed it. Now circumstances were changing and rapidly.

Dick Jacobs had little political savvy when he first showed interest in the city and its baseball team. But he was a quick study, a man who did not delude himself about the limits of his knowledge. His quiet manner belied the fact that he was always working, gathering information about the city and those who made it work.

Everyone around him was a source and he politely used those sources to gain needed insights into his interests. He did not suffer fools and was quick to judge who might be helpful to him and who might not.

In this way, he gained an edge on Modell in the maneuvering for a new stadium. Modell waited for the city to call him, Jacobs had his strategy in place before most even knew there was any need for one.

For all of the love for the Browns and Indians, there was a resentment toward supporting the teams with public money, part of a psychology that had plagued the city from its populist days. There was an underlying suspicion that progress actually meant that someone was taking unfair advantage of the public. This shadowy mistrust would manifest itself in many ways in the succeeding years around the stadium issue.

As far as Dick Jacobs was concerned, there was no question that the city needed a new stadium and so did he. He needed it to succeed with the Indians and did not hesitate in his efforts to achieve that end.

The organization that had attempted to build a domed stadium had acquired 28 acres of land in what was called the Gateway area on the site of the old Central Market at Ontario and Carnegie Avenues. Jacobs looked at this area as the location of a new stadium, first proposing a 44,000-seat stadium that could roll out another 28,000 seats for football. It was an effort at compromise, but in truth, all parties wanted an outdoor baseball-only facility.

That included Modell who found himself in financial straits. Free agency in the National Football League had changed the economics of the game, and the maintenance of the old stadium was unexpectedly expensive. It was clear that the new baseball facility would cost him a tenant, and the likelihood of there being enough money available to build two stadiums appeared remote. He had no choice but work on a plan to renovate Municipal Stadium.

Modell proposed a renovation of the facility that would modernize it and cost taxpayers less than $100 million. The idea drew a lot of attention, but city hall appeared to be cold to the idea.

As the decade drew to a close it was clear that the Gateway site would hold a new ballpark if voters would pass a sin tax on alcohol and cigarettes. It was unclear what was going to happen to Municipal Stadium. No one knew it yet, but the uncertainty of the stadium’s fate would lead to the bitterest moment in Cleveland sports history.

Elsewhere, the city was enjoying itself. The once-shabby Flats area near the mouth of the Cuyahoga River had come to life as a retinue of bars and restaurants lined its banks, creating an atmosphere of gaiety that had not been seen in the city in years.

Boaters docked at the river’s edge and enjoyed the revelry. Acclaimed in the national media, Cleveland’s Flats became a symbol of a revived city that was basking in its apparent good fortune. A reported $2 billion worth of construction was altering its skyline. For the first time since the Depression, there was genuine optimism about the future.

Not only were the Flats burgeoning with excitement, but Playhouse Square and its grand theaters, which were on the verge of being razed in the 1970s, took on a new life, its marquees once more aglitter. Playhouse Square was once again developing into an entertainment district that could rival most cities. It was a prime example of what the city’s civic effort could achieve in preserving the town’s cultural heritage.

But amidst all the good news, came a dour note. It was announced in 1987 that one of the city’s most venerable and benevolent companies, Standard Oil of Ohio, known as Sohio, was being taken over by British Petroleum.

Sohio could trace its roots to the beginnings of John D. Rockefeller’s oil empire that began in the Flats in 1870. The wealth that he and his associates created became the foundation of Cleveland’s future cultural and commercial life Slowly, the red and white Sohio signs on gas stations were replaced by the green and yellow BP colors and another era faded away.

BP kept its American headquarters here for a few years, but ultimately moved to Chicago when it merged with Amoco. The loss of old businesses would be a recurring theme in the city as the manufacturing era faded, taking with it jobs and economic security.

The ominous shadow of globalization continued to be cast across a city that had allowed itself to dwell in the past.

When George Voinovich left the lieutenant governor’s job to run for mayor, he told those business leaders that urged him to return to Cleveland that it was his wish to run for governor some day.

He was reelected twice as mayor and it could be argued that his time in office was one of the most productive in the modern era.

Voinovich projected the city’s comeback image nationally, his administration winning three All-American City awards for Cleveland, which he in turn leveraged in a run for higher office.

In 1988, Voinovich ran for the U.S. Senate against Democrat Howard Metzenbaum and was thoroughly defeated, 57% to 43%. The following year he announced he would not seek reelection as mayor. He would run for governor in 1990 and win.

After a decade of progress and relative tranquility, the 1989 mayor’s race broke with the fury and force of an unexpected storm. It was a contest between the past and the future, the mentor and the pupil, the lion in winter and the tiger at dawn.

If George Voinovich could look back on his stewardship with some pride, Council President George Forbes could share in the glow. In the end, and not without some difficulties in style, the two performed well together and the city benefited from it.

Now with the mayor’s office vacant, Forbes eyed it warily. Business leaders urged him to run, especially Dick Jacobs who had developed a friendship with the council president. Forbes had been in city council for 25 years and had endured some of the most difficult years in the city’s history.

Some close to the campaign wondered whether Forbes had his heart in being mayor.

There was no doubt that his opponent, Michael White, had his heart in the race. Young, articulate, volatile and smart, White had grown up in the city council dominated by Forbes. He had learned the vagaries and manipulations and politics that governed that body and now he wanted to guide the city’s destiny.

There could not have been a clearer demarcation between the two eras than a contest between George Forbes and Mike White. If this was a moment of historical transition, the shifting of power would not take place in a quiet, well- ordered manner.

These were two strong- willed men who knew the streets of the city as well as the halls of government. It was apparent that they did not like each other and would conduct a bitter fight over the race. Forbes accused White of being a slum landlord and a wife beater, while White countered by calling Forbes’ wife a front person for shady investments.

White, a state senator at 38, used the city’s success against Forbes saying that wealthy investors were given special tax breaks without regard for the poor. It was as nasty a political campaign has the city had ever seen.

With two black candidates fighting for votes, the white community became the pivotal factor and there was no reservoir of good will residing there for Forbes. His talk show days on WERE in the 1970s where he had made light of racial issues came back to haunt him.

To many white West Side voters, Forbes symbolized the racial conflict in the city. Those close to Forbes knew that many of his actions were more theatrical than real, but the perception was enough to cost him any chance of election citywide.

He seemed to know it, too. During the campaign, as the polls mirrored the impossibility of it all, Forbes seemed to mellow and back off. He had served longer than any other person as the president of city council and had left his mark on the city in many ways.

And he had, as that old man asked ten years before, answered the question of people getting along downtown. Yet most of the progress in the decade was cosmetic, and failed to address the city and the region’s place in the on going globalization that was enveloping the world.

The 1980s proved to be, at best a brief respite from reality. The ghost of the Depression and the specter of globalization still loomed heavily on the future of Northeast Ohio.

Mike White won the election to become the first black mayor since Carl Stokes in 1971. The 1990s beckoned with promise. White appeared dynamic, driven toward maintaining the momentum that had been so hard to generate after the turmoil of the 1970s.

The upcoming decade would be bittersweet, full of triumph and disaster and Mike White would ride it through as the longest- sitting mayor in Cleveland’s history. But the city mattered less and less to the future and prosperity of the region.

There continued to be a desperate need to confront the reality of the region’s place in the world.

The next chapter: “Cleveland in the 1990s” by Mike Roberts is here

1979 CSU

1979 CSU