original link is here

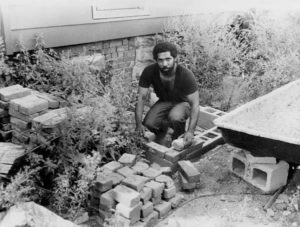

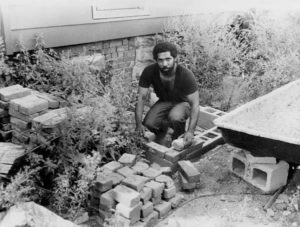

@CleCityCouncil Member Lonnie Burten (1978). Lonnie built homes in his neighborhood for residents of his ward. (photo: Cleveland Memory)

Roldo Bartimole writes about late Cleveland Councilperson Lonnie Burten Jr. in 2009

Sometimes you try to put people into boxes they don’t fit into. Mayor Frank Jackson is one of those people difficult to place. At least for me.

Is he just another politician? Or is he, as he says, “the right man” for the times. These not so good times.

I talked to Mayor Jackson because I happen to look at an old clipping that told me something about him and where he came from. I wanted to know more.

The clip was something I wrote in 1984 about the death of Lonnie Burten. Burten had been the Councilman of Ward 5, the city’s poorest ward, in Jackson’s Central area. Jackson didn’t succeed Burten after he died but he did eventually take that seat. He became a rescuer of that depressed ward. As its Councilman, Jackson brought it bundles of federal money.

Lonnie Burten had toppled two of the toughest old-time black politicians – Charlie Carr and Jimmy Bell. He got shot by someone during one of the campaigns against Carr. He survived that attack.

However, he died by heart attack at 40. I wrote upon Burten’s death: “Burten had the potential to become a true folk here. He did not achieve that status because he seemed to lack focus for his tremendous energy and thus the impact that creates legends.”

Burten and Jackson were youthful friends. When Jackson moved to 38th and Central, “Burten was the first person to knock on our door” and they became friends over the years. Burten went to college; Jackson to the Army.

People told Burten he was crazy” to run against Carr. Crazy enough to get shot but live to defeat the legendary Carr in 1981. Jackson and the late David Donaldson, despite the danger, campaigned with Burten.

Burten later tried to topple Council President George Forbes. He came within a vote of winning. Councilman Mike White put so much pressure on first-term Councilman (now judge) Larry Jones that Jones changed his vote from Burten to Forbes.

I told Lonnie that he needed 13 votes not just 11 votes,” recalled Jackson.

Preston Terry III succeeded Burten with Jackson”s help. But, as Jackson puts it, things went awry” and Jackson ran and defeated Terry in 1989.

Jackson laughed. He didn”t really want to be a Councilman. He was a city prosecutor at the time. He laughed again because he said, I didn”t want to be Council President,” followed by I didn’t want to be Mayor either.” It seems Jackson rises without any visible passion for power.

And that’s the strange thing. I believe him. From time to time for years I would make it up to Jackson’s Council office for talks. He never gave me the impression of wanting a higher office. He did have very strong opinions and I’d say a streak of stubbornness for his views.

But he also always played his cards close to the chest.

Mayor Jackson’s re-election spokesman Tom Andrzejewski said, “It’s still painful” for Jackson when I asked to talk to the Mayor about Burten’s influence upon him.

Jackson, in his low key way, said, “He passed away. It bothered me. We were pretty close.”

Jackson did say that he often thinks of Burten.

Burten was a larger than life person though likely pretty much forgotten or unknown to most Clevelanders.

Burten, I wrote in 1984, was always a study in contrasts. Avoiding drink, meat and smoking and apparently in good physical condition, he died of a heart attack. He was stricken while demolishing a house he once lived in on East 38th Street. He had lived in a corner of the house, which was heated by a kerosene space heater. Damage from a fire had made the house uninhabitable.

The fire had destroyed many of Burten’s belongings. Among the rubbish a visiting reporter found a leather-bound copy of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. Burten gave the copy to him.

He was a politician, a ghetto philosopher, a carpenter, auto mechanic, even an artist. One of his pieces, a multi-media portrait of an elderly black man, hangs in an office at Case Western Reserve University.”

He had a natural and charismatic flair,” said a professor told me.

He told me Burten had aspirations of being an academic but he told Burton his future was in politics, not academia.

Isn’t that what Cleveland needs right now? Someone with charisma. Unfortunately, Burten died. And it’s not clear he ever would have been able to go as far as Jackson has.

Jackson says he’s the right man to be mayor of Cleveland at this time. It’s clear to me that he was in the right place to take advantage of Jane Campbell’s inability to understand Cleveland politics. She was there for the picking; he for the taking.

I’ve been curious about whether Mayor Jackson had an ideology behind his political ambitions. It doesn’t seem so.

He does say “You always remember where you came from. You always go back home.” That’s his political reference point.

I believe he means it, too.

However, Jackson has been a mayor – unlike, say Dennis Kucinich – who has gone along with all the major projects that don’t seem so favorable for the economically deprived. He favors the Medical Mart and Convention Center, the expensive Port Authority relocation and all kinds of development subsidies.

Though he says of his philosophy, “You can’t live large when others are suffering.”

I don”t believe he’s living large. He laughs when people say he doesn’t really live in his home in the deprived Central area. “They say I really live in Shaker,” he says laughing.

Maybe Frank Jackson is the right person to be mayor of Cleveland right now. But for how long? I asked him how long he thought he wanted to be Mayor of Cleveland.

He says he wants to build on his foundation. He sees balancing the budget as a major achievement. It is an achievement when so much of government is drowning in red ink. But it’s a holding action.

The closest he comes to giving a hint of when he’s likely ready to leave the office is this: “I don”t want to be an impediment to my own purpose.” It’s often hard for politicians to recognize that point.

Jackson is a low key kind of guy. He projects a steady hand at the helm, even if that”s the mark of a caretaker Mayor.

The person who upends him will have to offer Clevelanders – and voters will have to be ready to accept – some flair and excitement. They will have to be a sharp contrast to Jackson.

It may not be long, I believe, when Cleveland will want someone who gives them something to look forward to, some spark and flair. Someone who will promise more than a balanced budget.

I don’t think it’s this election. I don’t think we can wait too much longer. Cleveland needs a big lift.

![]()

Councilman Lonnie Burten (center, with beard-Press Collection)

Councilman Lonnie Burten (center, with beard-Press Collection)