From The City Club of Cleveland 9.20.22

Watch The City Club of Cleveland debate between the two candidates for Cuyahoga County Executive: Chris Ronayne and Lee Weingart.

www.teachingcleveland.org

Links to all the LWV and partners issue forum videos 2016-2019

On December 11, 2020, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) adopted a new policy prioritizing racial and economic equity when making regional decisions about highway interchanges. NOACA is the first metropolitan planning organization (MPO) in the state to require this level of analysis for proposed highway interchange projects. Previously, decisions were made primarily focused on the impact of traffic flow and safety; with the new policy, consideration will be given to economic development, environmental justice, quality of life, transit and bike use, and racial equity.

This new policy follows decades of highway additions and expansions that encouraged suburban and exurban sprawl at the expense of the urban core – a practice that is often cited as a contributing factor to the region’s racial segregation, persistent economic inequality, generational urban poverty, and struggling school systems.

Many supporters of the policy believe it is long overdue – and hope it will lead to greater cooperation to strengthen the region as a whole, rather than pitting communities against each other in competition for jobs and new development. Others question the practicality of any continued suburban expansion given the region’s flat population growth.

Join us as three regional leaders discuss the policy and its short- and long-term implications for the future of Northeast Ohio.

The livestream will be available beginning at 12 p.m. here:

www.cityclub.org/forums/2021/02/03/sprawl-vs-smart-growth-building-an-equitable-and-thriving-region?fbclid=IwAR2GQ2U4uYR3mYhumaAoeeIUDSqfuAqID7u2O-wHAYcdYHsbrOJjB3WWmRQ

Produced and hosted by The City Club of Cleveland. Community partner: League of Women Voters of Greater Cleveland

PLAIN DEALER REPORT: A REGION UNITING

Read The Plain Dealer’s 2007 series on Northeast Ohio’s push towards a regional government

The Moral Implications of Regional Sprawl by Bishop Anthony Pilla 1996

Regional Cooperation in Northeast Ohio

or

How to get 59 Civic Entities to Play Together

Panelists:

Armond Budish, Cuyahoga County Executive

Eddy Kraus, Director of Regional Collaboration, Cuyahoga County

Moderator: Tom Beres, WKYC-TV

Co-sponsored by:

Case Western Reserve University’s Siegal Lifelong Learning,

City Club of Cleveland,

Cleveland Jewish News Foundation,

League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland

Wednesday June 17, 2015

Held at the Siegal Facility in Beachwood, Ohio

ONEKAMA VILLAGE, Mich.—Michigan has 1,773 municipalities, 609 school districts, 1,071 fire departments and 608 police departments. Gov. Rick Snyder wants some of them to disappear.

The governor is taking steps to bring about the consolidation of municipal services, even whole municipalities, in order to cut budgets and eliminate redundant local bureaucracies. His blueprint, which relies on legal changes and financial incentives, calls for a “metropolitan model” of government that would combine resources across cities and their suburbs.

In doing so, Mr. Snyder, a Republican, is taking aim at that twig of American government so cherished by many citizens—the town hall. The long national tradition of hyperlocal government prevails in much of the Northeast and Midwest, with their crazy quilts of cities, towns, villages and townships.

“You do have to ask: ‘Boy, do we really need 1,800 units of government?'” says Mr. Snyder’s budget director, John Nixon. “Everybody likes their independence, and that’s nice to have. But if you’re not careful, it can cost you a lot more money.”

Around the country public officials are asking themselves similar questions. Plunging property-tax receipts and rising pension and health-care costs have pushed many municipalities to the brink of financial collapse. The idea is that local governments can operate with fewer workers and smaller budgets if they do things like combine fire departments, create regional waste authorities and fold towns and cities into counties.

But selling the notion in small communities like Onekama is no easy job. Public officials have floated a proposal to merge this village of 1,500 along Lake Michigan into the township that encircles it. Some residents worry that a leaner government risks becoming a less responsive one.

Snow plowing already has emerged as a potential sticking point. If the merger passes a vote later this year, Manistee County would take over snow removal, and Onekama’s quiet streets would be among the last sections cleared.

Bonnie Miller, a village resident for 43 years who emerged as an early opponent of the merger, doesn’t want anyone to mess with the current plowing schedule. “At five in the morning, you can hear the plow truck is already out,” she says.

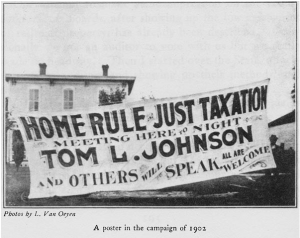

Over the years, consolidation proposals haven’t fared well with voters. Of the 105 referendums on city-county mergers since 1902, only 27 have passed, the most recent in 2000, when Louisville, Ky., merged into Jefferson County, according to David Rusk, a Democratic ex-mayor of Albuquerque and a proponent of consolidation. Last year, voters vetoed a merger of Memphis, Tenn., with Shelby County. In March, Memphis voters approved a merger of the city and county school systems, over strong suburban opposition. The county board of education has sued to block the merger.

Proponents of consolidation come from both ends of the political spectrum. Some conservatives argue that having fewer layers and divisions of government is cost-efficient and improves the economic climate by streamlining regulation and taxation. Some liberals support eliminating local-government boundaries that they say have cemented economic and racial disparities between cities and surrounding towns.

Researchers, however, have raised questions about whether such consolidation actually delivers significant savings. Typically, they say, only a few administrative positions overlap between jurisdictions, and further savings can’t be realized without compromising service. Public-safety agencies, for example, need a certain staff level to ensure the response times that residents demand.

A 2004 study by Indiana University’s Center for Urban Policy and the Environment found that costs creep back in, partly because bigger pools of employees can negotiate for better wages, offsetting the savings of job cuts. Academic studies of Jacksonville, Fla.’s combination with Duval County, and Miami’s merger with Dade County found that costs actually rose post-merger as new bureaucracies emerged.

In a study of Wheeling, W.Va.’s proposed merger with surrounding Ohio County, Mr. Rusk, the ex-mayor of Albuquerque, estimated that the potential cost savings would be barely 2% of the combined budget, because the overlap of services wouldn’t be as extensive as expected.

Mr. Rusk says the benefits of consolidation don’t necessarily come from cost savings. Fragmentation retards economic growth, he says, “not so much because of waste and duplication of services as an inability to unify a region’s resources” in everything from business development to road repair.

ENLARGE

ENLARGEVarious state legislatures are moving to spur consolidation. New Jersey, which has 566 municipalities, recently made it easier for communities to pursue mergers, and several are contemplating it. In New York state, which has more than 1,547 overlapping local governments—a system Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo once called “a ramshackle mess”—the Senate passed a bill in 2009 that gave voters the power to consolidate local municipalities and services. In Indiana, which has 1,008 townships, a legislative panel this year unanimously backed offering financial incentives to local governments that seek efficiencies through consolidation.

Michigan’s laws make municipal mergers difficult. Minimum-staffing requirements and prevailing-wage laws protect public employees and make it hard to cut payroll costs. Thus far, only two mergers have occurred: The city and township of Battle Creek, and two cities and a village in the sparsely populated Upper Peninsula.

Gov. Snyder has pushed legislators to dismantle those barriers. The Legislature earlier this year strengthened the state’s powers to take control of the finances of failing cities, empowering so-called emergency financial managers to void contracts, sidestep elected officials and dissolve municipalities.

While the governor can’t force consolidations, he is trying to coax financially troubled municipalities to pursue them. He is withholding about $200 million of funds for cities in need, making that aid contingent on evidence of consolidation of services such as fire departments and trash collections. His budget sets aside $5 million in transition aid for communities seeking mergers.

Similar incentives are being offered to school districts to share services such as busing, or to merge altogether. In addition, the governor has proposed a new policy that would in effect blur the existing school-district boundary lines.

“It is an evolutionary process, starting with service consolidation.” Gov. Snyder said in an interview.

The Detroit suburb of Hazel Park, in Oakland County, is considering merging its fire department with neighboring Ferndale’s. North of Hazel Park, the suburb of Pleasant Ridge is discussing sharing police and fire services with two of its neighbors.

“The economic reality has come home to roost,” said L. Brooks Patterson, county executive of Oakland County. “They are going to have to consolidate or find themselves in the cold grip of an emergency financial manager.”

ENLARGE

ENLARGEGov. Snyder plans to introduce legislation to ease city-county mergers and allow for the creation of metropolitan zones to coordinate services and economic-development efforts. His hope is for affluent suburbs to share resources with fiscally strapped cities. Such an effort is already under way for Grand Rapids and Kent County.

Today’s fragmented governments grew out of voter demands for home rule and tighter control over local resources such as emergency services and schools. Voters tend to protect those resources, even if it means paying more for them. “Local voters almost never approve voluntary mergers,” says Mr. Rusk.

Earlier this year, half a dozen struggling communities in Oakland County held votes on property-tax increases to avoid consolidation of services with neighboring towns or the county. All but one of the increases passed comfortably.

In Hazel Park, one of the county’s poorest communities, residents voted overwhelmingly for a five-year tax increase to avert deep cuts to the police and fire departments, whose costs, including retiree benefits, account for 64% of the city’s $13.7 million budget.

Larry Wallace, a 46-year-old father of six, stood up at a public meeting to endorse the higher tax. He said he moved to Hazel Park two decades ago after he was robbed in his house in Detroit and a gun was held to his five-year-old daughter’s head. He said he had waited eight hours for Detroit police, but they never showed. “I will pay whatever to live somewhere safe for me and my family,” he said.

In Onekama, two governments—the village’s and the township’s—operate out of single-story buildings half a block apart on Main Street. Each employs a clerk and a treasurer. Each has an elected board of trustees. The village has a president to run its affairs; the township, a supervisor.

Many residents like it that way. Township residents pay lower taxes in return for a mostly hands-off administration that controls public access to Portage Lake. Village residents pay higher taxes for services that include maintaining a park on the lake and the early-morning snow plowing.

Several years ago, the two governments came together over a shared interest: the health of the lake. Concerns about aging septic systems in lake-side cottages spurred the passage of a new septic ordinance for both areas.

ENLARGE

ENLARGEThe village and township then began cooperating on a plan to protect the lake. In 2009, both the village and township approved a special tax to help protect the watershed—a vote described by local officials as a turning point.

Next came a joint master plan, and late last year, Village President Bob Blackmore, a retired auto executive, and Township Supervisor David Meister, a farmer and muscle-car enthusiast, began discussing an outright merger. Their goal was to avoid duplication of services and to jointly seek resources.

Under the proposal they are considering, the village government would be dissolved and the township would take over. Village residents would see their tax bills shrink, and township residents would see them stay the same. A couple of part-time administrative jobs would be eliminated. State funds to facilitate the transition could sweeten the deal.

But some village residents worry the plan will somehow change the character of their community, that a township government will not value what the village does.

Ms. Miller, who runs a summer fruit stand in the village, initially called the proposed merger a “hostile takeover” by the township.

Some township residents also are wary. Jim Trout, a retiree from Grand Rapids who recently moved from the village to the township, says he fears a merger with the village, whose voters he says are more politically active, will bring more demands, and costs, for municipal services.

“If they demand amenities, they can go down and live in urbanland,” said Mr. Trout. “I chose to live here.”

Public meetings that began in February raised a host of questions, recalls Mr. Meister, the township supervisor: “What’s going to happen to their streets? Is the park system going to change? Will we have a new form of government? Who is going to lose their jobs?”

Mr. Meister is trying to work out a way for villagers to pay more to retain services such as early plowing.

Another public meeting is slated for Wednesday to include summer residents. Officials plan to address concerns raised at earlier meetings and to outline what the new government would look like. Residents will vote later this year.

“It will happen either now or later,” says Mr. Blackmore, the village president. “It is going to happen.”

Ms. Miller, who says she’s beginning to soften her opposition, doubts the merger would be the end of the consolidation process. She sees Onekama ultimately being swallowed up by the county. “You can’t stand in the way of progress forever,” she says. “But sometimes you do like to see the little Norman Rockwell image of a quaint village.”

Write to Kate Linebaugh at kate.linebaugh@wsj.com

Sunday, January 25, 2004

Plain Dealer Reporter

Corrections and clarifications: The following published correction appeared on January 29, 2004:Because of a reporter’s error, a story on Sunday’s Page One incorrectly ranked the population of Louisville, Ky. Upon merging with its home county last January, Louisville became America’s 16th most populous city.

————————————————–

A REGION DIVIDED / Is there a better way?

Welcome to the city of Metro Cleveland. We’re new, but we suspect you’ve heard of us.

We’re the largest city in Ohio, by far. With 1.3 million residents, we’re the sixth-largest city in America. Right back in the Top 10.

Our freshly consolidated city covers 459 square miles on the Lake Erie shore. Our economic development authority, enriched through regional cooperation, wields the power to borrow a whopping $500 million.

So, yes, America, we have a few plans.

How do you like us now?

Merging Cleveland and Cuyahoga County into a single super-city is only one example of “new regionalism” being discussed across the country. In fact, it illustrates one of the most aggressive and seldom-used strategies to revive a metropolitan area by eliminating duplicated services, sharing tax dollars across political boundaries and planning with a regional view.

At the other end of the spectrum stand places like present-day Cleveland, a tired city with rigid boundaries watching helplessly as its wealth and jobs drain away.

In between are dozens of regions where city and suburbs agreed to plan new industries, or began sharing taxes, or staked out “green lines” to slow sprawl and encourage investment in urban areas, cooperative strategies aimed at lifting the whole region.

Some dreams came true and others did not. Regional government does not solve every problem or achieve overnight success, experts caution. But the evidence suggests it allows cities like Cleveland to do something not dared here in a long time. It allows them to dream.

Dream big.

“Regional government would let Cleveland compete in the new economy,” said Bruce Katz, a specialist in metropolitan planning for the Brookings Institution.

“Overnight, we’d become a national player,” said Mark Rosentraub, dean of the College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University.

“These ideas are not crazy,” insists Myron Orfield, a Minnesota state senator and one of the nation’s best-known proponents of regional planning. “Regionalism is centrist. It’s happening. Ohio is one of the few industrialized states that has not done anything.”

Orfield is often credited with popularizing new regionalism through his 1997 book, “Metropolitics.” It details regional partnerships he fostered in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, strategies like tax sharing.

In 1969, the seven counties surrounding the Twin Cities began sharing taxes from new business and industry, pooling the money and giving it to the communities that needed it most.

Designed to revive the cities, the plan worked so well that Minneapolis now sends taxes to its suburbs.

(SEE CORRECTION NOTE) These days, a newer model of regionalism is drawing policy planners and mayors to northern Kentucky. Louisville merged with its home county last year to form the Louisville/Jefferson County Metro Government, becoming America’s 23rd-largest city as Cleveland slipped to 34th.

Much of the messy work of merging city and county departments remains, but Louisville Mayor Jerry E. Abramson said his community is already enjoying cost savings and something more: rising self-esteem.

Louisville residents had brooded as civic rivals Nashville and Indianapolis used regional cooperation to lure jobs, people and major-league sports teams. Fearful of being left forever behind, voters approved a dramatic merger that had been rejected twice before.

“I think people saw that those cities were moving ahead more quickly,” Abramson said. “We decided we would do better speaking with one voice for economic growth.”

History suggests such unity would not come easy to Northeast Ohio. Look at a detailed map of Ohio’s most populous county, Cuyahoga, and you’ll see a kaleidoscope of governments: one county, 38 cities, 19 villages, two townships, 33 school districts, and dozens of single-minded taxing authorities.

The idea of huddling them behind a single quarterback is not new. At least six times since 1917, voters rejected plans for regional government, spurning the most recent reform plan in 1980.

“You know why? People like small-town atmosphere,” said Faith Corrigan, a Willoughby historian who raised her family in Cleveland Heights. “It’s been said Cleveland is the largest collection of small towns in the world.”

Any effort at civic consensus in Northeast Ohio also means bridging a racial divide, which helped to defeat the last three reform efforts. Black civic leaders suspected a larger, whiter city would dilute their hard-won influence and political power. Those sentiments remain.

“Yes, we’re fearful of less representation,” said Sabra Pierce Scott, a Cleveland City councilwoman who represents the Glenville neighborhood, which is mostly black. “It’s taken us a long time to get here.”

Meanwhile, residents of wealthy suburbs may see little to gain by sharing taxes with Cleveland, let alone giving up the village council.

“I think it’s almost a fool’s dream to think you could even accomplish it,” said Medina County Commissioner Steve Hambley.

Yet opposition to regional government is softening. Recently, Urban League director Myron Robinson told his board members that regional cooperation could give black children access to better schools and should be discussed.

Mayors of older suburbs, facing their own budget woes, are questioning the wisdom of paying for services that might be efficiently shared, like fire protection and trash collection.

And Cleveland business leaders, many of whom live in the suburbs, are emerging as some of the strongest supporters of regional sharing and planning. They say a strong city is essential to the region’s prosperity and that Cleveland cannot rise alone.

For models of what might work, they look to any one of a dozen metropolitan areas that forged regional partnerships in recent decades; and to a few impassioned local believers.

“If I were God for a day,” CSU’s Rosentraub declares, he would simply merge the city and county bonding powers behind a planning agency with teeth. He would create a $500 million revolving development fund, big enough to launch the kinds of projects that change skylines.

That kind of cooperation, Rosentraub said, would also send a message across the land. We’re big. We’re regional. We’re working together.

To comment on regional government or this story:

theregion@plaind.com, 216-999-5068