Dr. John Grabowski, Congressman Dennis Kucinich, James JT Toman and Greg Deegan discuss Mayor Tom L. Johnson (1901-1909) when Cleveland, OH was known as “The City on the Hill”

Created by: Nicole Majercak, Donald Majercak, Richard Kiovsky for Teaching Cleveland

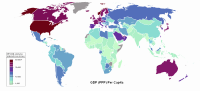

Georgism from Wikipedia

Georgism (also called Geoism) is an economic philosophy and ideology that holds that people own what they create, but that things found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all.[1] The Georgist philosophy is based on the writings of the economist, Henry George(1839-1897), and is usually associated with the idea of a single tax on the value of land. Georgists argue that a tax on land value iseconomically efficient, fair and equitable; and that it can generate sufficient revenue so that other taxes, which are less fair and efficient (such as taxes on production, sales and income), can be reduced or eliminated. A tax on land value has been described by many as aprogressive tax, since it would be paid primarily by the wealthy, and would reduce income inequality.[2]

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Main tenets

According to Henry George, political economy proceeds from the simple axiom: “People seek to satisfy their desires with the least exertion.”[3]George believed that although scientific experiments could not be carried out in political economy, theories could be tested by comparing different societies with different conditions and through thought experiments about the effects of various factors.[3] Applying this method, George concluded that many of the problems that beset society, such as poverty, inequality, and economic booms and busts, could be attributed to the private ownership of the necessary resource, land.

Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared equally by the people of a society rather than being owned privately. George held that people own what they create, but that things found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all.[1] In his publication Progress and Poverty George argued that: “We must make land common property.”[4] Although this could be done by nationalizing land and then leasing it to private parties, George preferred taxing unimproved land value, in part because this would be less disruptive and controversial in a country where land titles have already been granted to individuals.

It was Adam Smith who first noted the properties of a land value tax in his book, The Wealth of Nations:[5]

Ground-rents are a still more proper subject of taxation than the rent of houses. A tax upon ground-rents would not raise the rents of houses. It would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent, who acts always as a monopolist, and exacts the greatest rent which can be got for the use of his ground. More or less can be got for it according as the competitors happen to be richer or poorer, or can afford to gratify their fancy for a particular spot of ground at a greater or smaller expense.In every country the greatest number of rich competitors is in the capital, and it is there accordingly that the highest ground-rents are always to be found. As the wealth of those competitors would in no respect be increased by a tax upon ground-rents, they would not probably be disposed to pay more for the use of the ground. Whether the tax was to be advanced by the inhabitant, or by the owner of the ground, would be of little importance. The more the inhabitant was obliged to pay for the tax, the less he would incline to pay for the ground; so that the final payment of the tax would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent.

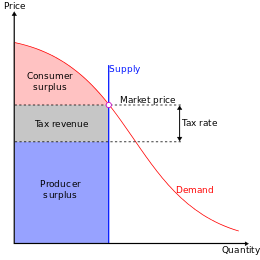

Standard economic theory suggests that a land value tax would be extremely efficient – unlike other taxes, it does not reduce economic productivity.[2] Nobel laureate Milton Friedman agreed that Henry George’s land value tax is potentially beneficial for society since, unlike other taxes, it would not impose an excess burden on economic activity (leading to “deadweight loss“). A replacement of other more distortionary taxes with a land value tax would thus improve economic welfare.[6]

Georgists suggest two uses for the revenue from a land value tax. The revenue can be used to fund the state, or it can be redistributed to citizens as a pension or basic income (or it can be divided between these two options). If the first option were to be chosen, the state could avoid having to tax any other type of income or economic activity. In practice, the elimination of all other taxes implies a very high land value tax, higher than any currently existing land tax. Introducing a high land value tax would cause the price of land titles to decrease correspondingly, but George did not believe landowners should be compensated, and described the issue as being analogous to compensation for former slave owners. Additionally, a land value tax would be a tax of wealth, and so would be a form of progressive taxation and tend to reduce income inequality. As such, a defining argument for Georgism is that it taxes wealth in a progressive manner, reducing inequality, and yet it also reduces the strain on businesses and productivity.

Georgists also argue that all economic rent (i.e., unearned income) collected from natural resources (land, mineral extraction, the broadcast spectrum, tradable emission permits,fishing quotas, airway corridor use, space orbits, etc.) and extraordinary returns from natural monopolies should accrue to the community rather than a private owner, and that no other taxes or burdensome economic regulations should be levied. Modern environmentalists find the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity appealing, and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform as a replacement for command and control regulation. This would entail substantial taxes or fees for pollution, waste disposal and resource exploitation, or equivalently a “cap and trade” system where permits are auctioned to the highest bidder, and also include taxes for the use of land and other natural resources.[citation needed]

[edit]Synonyms and variants

Most early advocacy groups described themselves as Single Taxers, and George endorsed this as being an accurate description of the philosophy’s main political goal – the replacement of all taxes with a land value tax. During the modern era, some groups inspired by Henry George emphasize environmentalism more than other aspects, while others emphasize his ideas concerning economics.

Some devotees are not entirely satisfied with the name Georgist. While Henry George was well-known throughout his life, he has been largely forgotten by the public and the idea of a single tax of land predates him. Some people now use the term “Geoism”, with the meaning of “Geo” deliberately ambiguous. “Earth Sharing”[7] “Geoism“,[8] “Geonomics” [9] and “Geolibertarianism“[10] (see libertarianism) are also preferred by some Georgists; “Geoanarchism” is another one.[11] These terms represent a difference of emphasis, and sometimes real differences about how land rent should be spent (citizen’s dividend or just replacing other taxes); but all agree that land rent should be recovered from its private recipients.

[edit]Influence

Georgist ideas heavily influenced the politics of the early 1900s, during its heyday. Political parties that were formed based on Georgist ideas include the Commonwealth Land Party, the Justice Party of Denmark, and the Single Tax League.

In the UK during 1909, the Liberal Government included a land tax as part of several taxes in the People’s Budget aimed at redistributing wealth (including a progressively graded income tax and an increase of inheritance tax). This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. The budget was passed eventually – but without the land tax. In 1931 the minority Labour Government passed a land value tax as part III of the 1931 Finance act. However this was repealed in 1934 by the National Governmentbefore it could be implemented. In Denmark, the Georgist Justice Party has previously been represented in Folketinget. It formed part of a centre-left government 1957-60 and was also represented in the European Parliament 1978-79. The influence of Henry George has waned over time, but Georgist ideas still occasionally emerge in politics. In the 2004 Presidential campaign, Ralph Nader mentioned Henry George in his policy statements.[12]

[edit]Communities

Several communities were also initiated with Georgist principles during the height of the philosophy’s popularity. Two such communities that still exist are Arden, Delaware, which was founded during 1900 by Frank Stephens and Will Price, and Fairhope, Alabama, which was founded during 1894 by the auspices of the Fairhope Single Tax Corporation.

The German protectorate of Jiaozhou Bay (also known as Kiaochow) in China fully implemented Georgist policy. Its sole source of government revenue was the land value tax of six percent which it levied on its territory. The German government had previously had economic problems with its African colonies caused by land speculation. One of the main aims in using the land value tax in Jiaozhou Bay was to eliminate such speculation, an aim which was entirely achieved.[13] The colony existed as a German protectorate from 1898 until 1914 when it was seized by Japan. In 1922 it was returned to China.

Georgist ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions.[14] Many municipal governments of the USA depend on real property tax as their main source of revenue, although such taxes are not “Georgist” as they generally include the value of buildings and other improvements, one exception being the town of Altoona, Pennsylvania, which only taxes land value.

[edit]Institutes and organizations

Various organizations still exist that continue to promote the ideas of Henry George. According to the The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, the periodicalLand&Liberty, established in 1894, is the “the longest-lived Georgist project in history”.[15] Also in the U.S., the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy was established in 1974 founded based on the writings of Henry George, and “seeks to improve the dialogue about urban development, the built environment, and tax policy in the United States and abroad”.[16] TheHenry George Foundation continues to promote the ideas of Henry George in the UK.[17] The IU, is an international umbrella organisation that brings together organizations worldwide that seek land value tax reform.[18]

[edit]Criticism

Although both advocated workers’ rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition to communism. He argued that, “The whole thing is… simply an attempt, decked out with socialism, to save capitalist domination and indeed to establish it afresh on an even wider basis than its present one.”[19] Marx also criticized the way land value tax theory emphasizes the value of land, arguing that, “His fundamental dogma is that everything would be all right if ground rent were paid to the state.”[19]

On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx’s ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[20][21][page needed] Fred Harrison provides a full treatment of Marxist objections to land value taxation and Henry George in “Gronlund and other Marxists – Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics”, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, (Nov 2003).[22]

George has also been accused of exaggerating the importance of his “all-devouring rent thesis” in claiming that it is the primary cause of poverty and injustice in society.[23] More recent critics have claimed that increasing government spending has rendered a land tax insufficient to fund government.[citation needed] Georgists have responded by citing a multitude of sources showing that the total land value of nations like the US is enormous, and more than sufficient to fund government.[24]

[edit]Notable people influenced by Georgism

- Matthew Bellamy – member of the alternative rock band,Muse [25]

- Ralph Borsodi [26]

- William F. Buckley, Jr. [27]

- Vince Cable – UK Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Liberal DemocratsDeputy Leader and Shadow Chancellor.

- Winston Churchill [28]

- Nick Clegg – Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, leader of the Liberal Democrats

- Clarence Darrow[29]

- Michael Davitt [30]

- Albert Einstein[31]

- Fred Foldvary, PhD – Lecturer in Economics, Santa Clara University[32]

- Henry Ford[33]

- M. Mason Gaffney, PhD – Economics professor at theUniversity of California at Riverside [34]

- David Lloyd George [28]

- George Grey [35]

- Walter Burley Griffin[36]

- Bolton Hall, New York City activist[37]

- Fred Harrison – Research Director of the London-based Land Research Trust[38]

- William Morris Hughes – seventh Prime Minister of Australia (1915–1923)[39]

- Bill Moyers[40]

- Aldous Huxley[41]

- Blas Infante [42]

- Mumia Abu-Jamal[43]

- Tom L. Johnson[44]

- Samuel M. Jones – Mayor ofToledo, Ohio (1897 to 1904)[45]

- Wolf Ladejinsky [46]

- Suzanne La Follette – American journalist &libertarian feminist [47]

- Elizabeth Magie,.[48]

- Ralph Nader[12]

- Francis Neilson – Actor, playwright, stage director, Member of the British House of Commons, avid lecturer, and author[49]

- Albert Jay Nock[50]

- Herbert Simon – Winner of theNobel Memorial Prize in Economics (1978)[51]

- Raymond A. Spruance[52]

- Joseph Stiglitz – Winner of theNobel Memorial Prize in Economics (2001)[53]

- Leo Tolstoy[54]

- William Simon U’Ren[55]

- William Vickrey – Winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (1996)[56]

- Frank Lloyd Wright[57]

- Sun Yat-sen [58]

[edit]See also

- Excess burden of taxation

- Mutualism

- Economic democracy

- Geolibertarianism

- Bolton Hall (activist), a proponent of the theory

- Progress and Poverty

- Protection or Free Trade

- Tragedy of the anticommons

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b Heavey, Jerome F. (07 2003). “Comments on Warren Samuels’ “Why the Georgist movement has not succeeded””. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 62(3): 593-599. Retrieved 29 July 2011. “human beings have an inalienable right to the product of their own labor”.

- ^ a b Land Value Taxation: An Applied Analysis, William J. McCluskey, Riël C. D. Franzsen

- ^ a b Progress and Poverty – “Introduction: The Problem of Poverty Amid Progress

- ^ George, Henry (1879). “2”. Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. VI. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ The Wealth of Nations Book V, Chapter 2, Article I: Taxes upon the Rent of Houses.

- ^ Foldvary, Fred E. “Geo-Rent: A Plea to Public Economists”. Econ Journal Watch (April 2005)[1]

- ^ Introduction to Earth Sharing,

- ^ Socialism, Capitalism, and Geoism – by Lindy Davies

- ^ Geonomics in a Nutshell

- ^ Geoism and Libertarianism by Fred Foldvary

- ^ Geoanarchism: A short summary of geoism and its relation to libertarianism – by Fred Foldvary

- ^ a bhttp://web.archive.org/web/20040828085138/http://www.votenader.org/issues/index.php?cid=7

- ^ Silagi, Michael and Faulkner, Susan N., , Land Reform in Kiaochow, China: From 1898 to 1914 the Menace of Disastrous Land Speculation was Averted by Taxation, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, volume 43, Issue 2, pages 167-177

- ^ Gaffney, M. Mason. “Henry George 100 Years Later”. Association for Georgist Studies Board. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 62, 2003, p. 615

- ^ http://www.lincolninst.edu/aboutlincoln/

- ^ “The Henry George Foundation”. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ The IU. “The IU”. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ a b Karl Marx – Letter to Friedrich Adolph Sorge in Hoboken

- ^ http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/mceachran_hgeorge_and_kmarx.html

- ^ Henry George’s Thought [1878822810] – $49.95 : Zen Cart!, The Art of E-commerce

- ^ 14 Gronlund and other Marxists – Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics | American Journal of Economics and Sociology, The | Find Articles at BNET

- ^ Critics of Henry George

- ^ Looking For Rents In All the Right Places

- ^ Muse return with new album The Resistance “Sure, he has already launched into a passionate soliloquy about Geoism (the land-tax movement inspired by the 19th-century political economist Henry George)“.

- ^ Carlson, Allan. The New Agrarian Mind: The Movement Toward Decentralist Thought in Twentieth-Century America Transaction Publishers, 2004 (pg 51).

- ^ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Buckley_HG.html William F. Buckley, Jr. Transcript of an interview with Brian Lamb, CSpan Book Notes, April 2–3, 2000

- ^ a b People’s Budget

- ^ Transcript of a speech by Darrow on taxation

- ^ Lane, Fintan. The Origins of Modern Irish Socialism, 1881-1896.Cork University Press, 1997 (pgs.79,81).

- ^ Two lettrs written in 1934 to Henry George’s daughter, Anna George De Mille. In one letter Einstein writes, “Men like Henry George are rare unfortunately. One cannot imagine a more beautiful combination of intellectual keenness, artistic form and fervent love of justice.“

- ^ Fred Foldvary’s website

- ^ Transcript of 1942 interview with Henry Ford in which he says, “The time will come when not an inch of the soil, not a single crop, not even weeds, will be wasted. Then every American family can have a piece of land. We ought to tax all idle land the way Henry George said — tax it heavily, so that its owners would have to make it productive“.

- ^ Mason Gaffney’s homepage

- ^ The Life of Henry George, Part 3 Chapter X1

- ^ Co-founder of the Henry George Club, Australia.

- ^ Leubuscher, F. C. (1939). Bolton Hall. The Freeman. January issue.

- ^ Fred Harrison’s website

- ^ “Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862 – 1952)”. Australian Dictionary of Biography: Online Edition.

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Za-TYGOE1O0&t=38m0s

- ^ Harrison, F. (1989). Aldous Huxley on ‘the Land Question’. Land & Liberty. May – June issue.

- ^ Arcas Cubero, Fernando: El movimiento georgista y los orígenes del Andalucismo : análisis del periódico “El impuesto único” (1911-1923). Málaga : Editorial Confederación Española de Cajas de Ahorros, 1980. ISBN 8450037840

- ^ Justice for Mumia Abu-Jamal

- ^ “Single Taxers Dine Johnson”. New York Times May 31, 1910.

- ^ “Henry George”. Ohio History Central: An Online History of Ohio History.

- ^ Andelson Robert V. (2000). Land-Value Taxation Around the World: Studies in Economic Reform and Social Justice Malden. MA:Blackwell Publishers, Inc. Page 359.

- ^ Suzanne La Follette: The Freewoman

- ^ Magie invented The Landlord’s Game, predecessor to Monopoly

- ^ “Henry George, The Scholar” – A Commencement Address Delivered by Francis Neilson at the Henry George School of Social Science, June 3, 1940.

- ^ Henry George: Unorthodox American by Albert Jay Nock

- ^ Quotes from Nobel Prize Winners Herbert Simon stated in 1978: “Assuming that a tax increase is necessary, it is clearly preferable to impose the additional cost on land by increasing the land tax, rather than to increase the wage tax — the two alternatives open to the City (of Pittsburgh). It is the use and occupancy of property that creates the need for the municipal services that appear as the largest item in the budget — fire and police protection, waste removal, and public works. The average increase in tax bills of city residents will be about twice as great with wage tax increase than with a land tax increase.“

- ^ Thomas B. Buell (1974). The Quiet Warrior. Boston: Little, Brown.

- ^ December 2010 video, in which Stiglitz calls Henry George a “great progressive” and advocates for the land tax

- ^ .Article on Tolstoy, Proudhon and George. Count Tolstoy once said of George, “People do not argue with the teaching of George, they simply do not know it“.

- ^ “Oregon Biographies: William S. U’Ren”. Oregon History Project. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. 2002. Archived from the original on 2006-11-10. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ Bill Vickrey – In Memoriam

- ^ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Wright_HG%27s_Remedy.html

- ^ Trescott, P. B. (1994). Henry George, Sun Yat-sen and China: more than land policy was involved. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53, 363-375.

Henry George from Wikipedia

| Classical economics | |

|---|---|

Henry George |

|

| Born | September 2, 1839 |

| Died | October 29, 1897 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | American |

| Contributions | Georgism; studied land as a factor in economic inequalityand business cycles; proposed land value tax |

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American writer, politician and political economist, who was the most influential proponent of the land value tax, also known as the “single tax” on land. He inspired the economic philosophy known asGeorgism, whose main tenet is that people should own what they create, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all humanity. His most famous work, Progress and Poverty (1879), is a treatise on inequality, the cyclic nature of industrial economies, and the use of the land value tax as a possible remedy.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Early life and marriage

George was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a lower-middle class family, the second of ten children of Richard S. H. George and Catharine Pratt (Vallance) George. His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He returned to Philadelphia after 14 months at sea to become an apprentice typesetter before settling in California. After a failed attempt at gold mining he began work with the newspaper industry during 1865, starting as a printer, continuing as a journalist, and ending as an editor and proprietor. He worked for several papers, including four years (1871–1875) as editor of his own newspaper San Francisco Daily Evening Post.

In California, George became enamored of Annie Corsina Fox, an eighteen-year-old Australian girl who had been orphaned and was living with an uncle. The uncle, a prosperous, strong-minded man, was opposed to his niece’s impoverished suitor. But the couple, defying him, eloped and married during late 1861, with Henry dressed in a borrowed suit and Annie bringing only a packet of books. The marriage was a happy one and four children were born to them. Fox’s mother was Irish Catholic, and while George remained an Evangelical Protestant, the children were raised Catholic. On November 3, 1862 Annie gave birth to future United States Representative from New York, Henry George, Jr. (1862–1916). Early on, even with the birth of future sculptor, Richard F. George(1865–September 28, 1912),[1][2][3] the family was near starvation, but George’s increasing reputation and involvement in the newspaper industry lifted them from poverty.

George’s other two children were both daughters. The first was Jennie George, (c. 1867 – 1897), later to become Jennie George Atkinson.[4] George’s other daughter was Anna Angela George, (b. 1879), who would become mother of both future dancer and choreographer, Agnes de Mille [5] and future actress Peggy George, (who was born Margaret George de Mille).[6][7]

[edit]Economic and political philosophy

George began as a Lincoln Republican, but then became a Democrat, once losing an election to the California State Assembly. He was a strong critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors.

One day during 1871 George went for a horseback ride and stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He later wrote of the revelation that he had:

| “ | I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, ‘I don’t know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.’ Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.[8] | ” |

Furthermore, on a visit to New York City, he was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that long-established city were much worse off than the poor in less developed California. These observations supplied the theme and title for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty, which was a great success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by social and technological advances in a free market economy is possessed by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the main cause of poverty. George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and indicated that such a system was equivalent to slavery—a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery.

George was in a position to discover this pattern, having experienced poverty himself, knowing many different societies from his travels, and living in California at a time of rapid growth. In particular he had noticed that the construction of railroads in California was increasing land values and rents as fast or faster than wages were rising.

During 1880, now a popular writer and speaker,[9] George moved to New York City, becoming closely allied with the Irish nationalist community despite being of English ancestry. From there he made several speaking journeys abroad to places such asIreland and Scotland where access to land was (and still is) a major political issue. During 1886 George campaigned for mayor of New York City as the candidate of the United Labor Party, the short-lived political society of the Central Labor Union. He polled second, more than the Republican candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The election was won by Tammany Hall candidate Abram Stevens Hewitt by what many of George’s supporters believed was fraud. In the 1887 New York state elections George came in a distant third in the election for Secretary of State of New York. The United Labor Party was soon weakened by internal divisions: the management was essentially Georgist, but as a party of organised labor it also included some Marxist members who did not want to distinguish between land and capital, many Catholic members who were discouraged by the excommunication of FatherEdward McGlynn, and many who disagreed with George’s free trade policy. Against the advice of his doctors, George campaigned for mayor again during 1897, this time as an Independent Democrat.

[edit]Death

Henry George died of a stroke four days before the election.[10] An estimated 100,000 people attended his funeral on Sunday, October 30, 1897 where the Reverend Lyman Abbott delivered an address,[11] “Henry George: A Remembrance”.[12]

[edit]Policy proposals

[edit]Single tax on land

Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared by society rather than being owned privately. The clearest statement of this view is found in Progress and Poverty: “We must make land common property.”[13] By taxing land values, society could recapture the value of its common inheritance, and eliminate the need for taxes on productive activity.

Modern-day environmentalists[who?] have agreed with the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity – and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform, including substantial taxes or fees on pollution as a replacement for “command and control” regulation.

[edit]Free trade

George was opposed to tariffs, which were at the time both the major method of protectionist trade policy and an important source of federal revenue (the federal income tax having not yet been introduced). Later in his life, free trade became a major issue in federal politics and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen.

[edit]Chinese immigration

Some of George’s earliest articles to gain him fame were on his opinion that Chinese immigration should be restricted.[14] Although he thought that there might be some situations in which immigration restriction would no longer be necessary and admitted his first analysis of the issue of immigration was “crude”, he defended many of these statements for the rest of his life.[15] In particular he argued that immigrants accepting lower wages had the undesirable effect of forcing down wages generally. He acknowledged, however, that wages could only be driven down as low as whatever alternative for self-employment was available.

[edit]Secret ballots

George was one of the earliest, strongest and most prominent advocates for adoption of the Secret Ballot in the U.S.A. [16]

[edit]Hard currency and national debt

George supported government issued notes such as the greenback rather than gold or silver currency or money backed by bank credit.[17]

[edit]Subsequent influence

In the United Kingdom during 1909, the Liberal Government of the day attempted to implement his ideas as part of the People’s Budget. This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. George’s ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions.

Fairhope, Alabama was founded as a colony by a group of his followers as an experiment to try to test his concepts.

Although both advocated worker’s rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition tocommunism.[18] On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx’s ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[19]

Henry George’s popularity decreased gradually during the 20th century, and he is little known today. However, there are still many Georgist organizations in existence. Many people who still remain famous were influenced by him. For example, George Bernard Shaw [2], Leo Tolstoy’s To The Working People [3] , Sun Yat Sen [4], Herbert Simon [5], and David Lloyd George. A follower of George, Lizzie Magie, created a board game called The Landlord’s Game in 1904 to demonstrate his theories. After further development this game led to the modern board game Monopoly. [6]

J. Frank Colbert, a newspaperman, a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives and later the mayor of Minden, joined the Georgist movement during 1927. During 1932, Colbert addressed the Henry George Congress at Memphis, Tennessee.

Also notable is Silvio Gesell‘s Freiwirtschaft [7], in which Gesell combined Henry George’s ideas about land ownership and rents with his own theory about the money system and interest rates and his successive development of Freigeld.

In his last book, Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community?, Martin Luther King, Jr referenced Henry George in support of a guaranteed minimum income.[8] George’s influence has ranged widely across the political spectrum. Noted progressives such as consumer rights advocate (and U.S. Presidential candidate) Ralph Nader [9] andCongressman Dennis Kucinich [10] have spoken positively about George in campaign platforms and speeches. His ideas have also received praise from conservative journalistsWilliam F. Buckley, Jr. [11] and Frank Chodorov [12], Fred E. Foldvary [13] and Stephen Moore [14]. The libertarian political and social commentator Albert Jay Nock[15] was also an avowed admirer, and wrote extensively on the Georgist economic and social philosophy.

Mason Gaffney, an American economist and a major Georgist critic of neoclassical economics, argued that neoclassical economics was designed and promoted by landowners and their hired economists to divert attention from George’s extremely popular philosophy that since land and resources are provided by nature, and their value is given by society, they – rather than labor or capital – should provide the tax base to fund government and its expenditures.[20]

The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [16], an incorporated “operating foundation,” also publishes copies of George’s work on economic reform and sponsors academic research into his policy proposals [17].

[edit]Economic contributions

George developed what he saw as a crucial feature of his own theory of economics in a critique of an illustration used by Frédéric Bastiat in order to explain the nature of interestand profit. Bastiat had asked his readers to consider James and William, both carpenters. James has built himself a plane, and has lent it to William for a year. Would James be satisfied with the return of an equally good plane a year later? Surely not! He’d expect a board along with it, as interest. The basic idea of a theory of interest is to understand why. Bastiat said that James had given William over that year “the power, inherent in the instrument, to increase the productivity of his labor,” and wants compensation for that increased productivity.

George did not accept this explanation. He wrote, “I am inclined to think that if all wealth consisted of such things as planes, and all production was such as that of carpenters — that is to say, if wealth consisted but of the inert matter of the universe, and production of working up this inert matter into different shapes, that interest would be but the robbery of industry, and could not long exist.” But some wealth is inherently fruitful, like a pair of breeding cattle, or a vat of grape juice soon to ferment into wine. Planes and other sorts of inert matter (and the most lent item of all—- money itself) earn interest indirectly, by being part of the same “circle of exchange” with fruitful forms of wealth such as those, so that tying up these forms of wealth over time incurs an opportunity cost.

George’s theory had its share of critiques. Austrian school economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, for example, expressed a negative judgment of George’s discussion of the carpenter’s plane. On page 339 of his treatise, Capital and Interest, he wrote:

In the first place, it is impossible to support his distinction of the branches of production into two classes, in one of which the vital forces of nature are supposed to constitute a special element which functions side by side with labour, and in the other of which this is not true. […] The natural sciences have long since proved to us that the cooperation of nature is universal. […] The muscular movements of the person using the plane would be of little use, if they did not have the assistance of the natural forces and properties of the plane iron.

Later, George argued that the role of time in production is pervasive. In “The Science of Political Economy”, he writes:[21]

[I]f I go to a builder and say to him, “In what time and at what price will you build me such and such a house?” he would, after thinking, name a time, and a price based on it. This specification of time would be essential…. This I would soon find if, not quarreling with the price, I ask him largely to lessen the time…. I might get the builder somewhat to lessen the time… ; but only by greatly increasing the price, until finally a point would be reached where he would not consent to build the house in less time no matter at what price. He would say [that the house just could not be built any faster]….The importance … of this principle that all production of wealth requires time as well as labor we shall see later on; but the principle that time is a necessary element in all production we must take into account from the very first.

According to Oscar B. Johannsen, “Since the very basis of the Austrian concept of value is subjective, it is apparent that George’s understanding of value paralleled theirs. However, he either did not understand or did not appreciate the importance of marginal utility.”[22]

Another spirited response came from British biologist T.H. Huxley in his article “Capital – the Mother of Labour,” published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. Huxley used the principles of energy science to undermine George’s theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive.

George’s early emphasis on the “productive forces of nature” is now dismissed even by otherwise Georgist authors.

[edit]See also

- Geolibertarianism

- Georgism

- Henry George Theorem

- Land Value Tax

- Left-libertarianism

- New York City mayoral elections

- Spaceship Earth

- Tammany Hall#1870-1900

- Charles Hall – An early precursor to Henry George

- History of the board game Monopoly

[edit]References

- Notes

- ^ Obituary, New York Times

- ^ http://www.guariscogallery.com/browse_by_artist.html?artist=595

- ^ “SINGLE TAXERS DINE JOHNSON; Medallion Made by Son of Henry George Presented to Cleveland’s Former Mayor”, The New York Times – May 31, 1910

- ^ Obituary – Th New York Times, May 4, 1897

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0210350/bio

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0313565/bio

- ^ http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss11_bioghist.html

- ^ Quoted in Nock, Albert Jay. “Henry George: Unorthodox American, Part I“.

- ^ According to his granddaughter Agnes de Mille, Progress and Poverty and its successors made Henry George the third most famous man in the USA, behind only Mark Twain andThomas Edison. [1]

- ^ “Henry George’s Death Abroad. London Papers Publish Long Sketches and Comment on His Career”. New York Times. October 30, 1897. Retrieved 2010-03-07. “The newspapers today are devoting much attention to the death of Henry George, the candidate of the Jeffersonian Democracy for the office of Mayor of Greater New York, publishing long sketches of his career and philosophical and economical theories.”

- ^ http://cooperativeindividualism.org/georgists_unitedstates-aa-al.html

- ^ http://cooperativeindividualism.org/abbott-lyman_on-henry-george.html

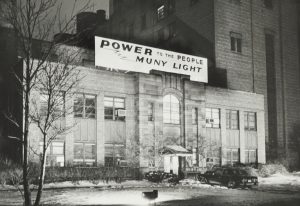

One Man Can Make A Difference by Roldo Bartimole

photo: Cleveland State University

photo: Cleveland State University

One Man Can Make a Difference

By Roldo Bartimole

It took a single person’s act in 1979 to save Cleveland’s public electric light system.

And no, that man wasn’t Mayor Dennis Kucinich.

It was a Plain Dealer reporter. His name was Bob Holden.

Mayor Kucinich had been forced by political pressure to put the Cleveland Municipal Light System, commonly known as Muny Light at that time, on the ballot. The measure asked voters to decide whether to sell or keep the troubled electric system. Muny produced no electric power itself. The city’s system owed its origin to the progressive politics of Mayor Tom L. Johnson in the early 1900s.

Kucinich and his administration worked exhaustively to save Muny. But without Holden’s act and the ensuing revolt at the Plain Dealer, it would not have been sufficient.

A Jan. 23 poll showed the ballot measure would go down by a 70 to 30 vote. Cleveland voters were tired of the constant disputes of the Kucinich administration. The poll revealed the voter frustration. On Feb. 27, 1979 the voters, however, made their choice.

Historically, the era of the 1960s was ending or over. In Cleveland, however, Kucinich kept it alive. He espoused an urban theory that urged progressives to concentrate on economic issues, not social issues. Progressives flocked to his administration from around the nation. He even drew Ralph Nader into the drama.

The two electric power companies had been involved in explosive disputes – legal and financial – for years. The city was suing the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI) for anti-trust violations and dirty tricks. A federal case was pending. Cleveland also disputed unusual high charges for power provided to Muny by CEI. Meanwhile, CEI tried numerous underhanded methods to weaken and destroy the city’s system. The aim was clearly to put the city out of the electricity business. CEI now is an operating company of First Energy Company of Akron.

So how did Bob Holden do it? He did it by being kicked off the story of how CEI had purposely damaged Muny Light.

But Holden didn’t go quietly.

Here’s what happened.

As the reporter assigned to cover CEI, Holden was delegated to report about the dispute between the two entities. In early 1979 series of articles was planned.

Before he got started, however, CEI complained about him to the Plain Dealer. They didn’t want Holden doing the reporting. They figured him as too tough. They also knew that the proof of the company’s bad behavior was readily available. Holden would not shy from collecting the data and writing it.

The editors folded under CEI’s pressure. Holden was pulled from the story. The reason editors gave was that Holden “would be unfair.” Not something reporters wanted to hear.

Since he hadn’t written a word how they determined bias was a mystery. How could they say that? The Plain Dealer editorial hierarchy was going out on a limb with that excuse. Reporters weren’t buying it.

At the time the Newspaper Guild, representing reporters, was strong and militant. Unlike today when reporters fear losing their jobs in a diminished newspaper business, reporters then were willing to fight management. The Guild voted to withhold bylines on articles and to picket the PD. This would reveal their displeasure about the censorship to the public. It would embarrass the editors. The Guild contract allowed reporters to withhold bylines.

Management buckled, though not totally.

These were tough times for media managers. In November 1978 WJW Channel 8 retracted a piece done by Bob Franken. Franken reported that a National City Bank Chairman Claude Blair wanted to deny refinancing city debt and force Cleveland into default to insure Mayor Dennis Kucinich’s defeat in the next mayoral election.

The station, under pressure from the bank, retracted the report. Ch. 8 news director Virgil Dominic read the rare retraction that said “We now find that all of the statements we made were inaccurate and there was absolutely no basis for the report.”

Franken resigned after the retraction was aired. He said, “I can only tell you that the story is not inaccurate. The story is 100 percent true. My sources, in this particular case, are incredibly good sources.”

“This in my mind,” he said, “was simply a matter of the power structure in the town getting its way.

Franken became an Emmy-winning reporter for CNN, covering the White House and Congress until he left in 2007.

Here’s how I explained the Holden situation in my newsletter Point of View in February 1979:

“The Guild followed by voting to withhold bylines and picketing the newspaper to call attention to the PD censorship. With TV coverage, particularly on Ch. 3, and radio, particularly on WERE, the entire community found out about the latest PD censorship.

“To get out of the spotlight, management agreed to meet with Guild members to hammer out a compromise.

“The two sides met for some eight hours at the Leather Bottel, a restaurant-bar, and an agreement was reached. It became the joint statement of the Guild and management:

“Plain Dealer reporter Robert Holden, for the month of February, will, as assigned, fill in for the vacationing book editor.

“At the end of February, he will report to the city editor as general assignment reporter under the usual PD standards.”

The two sides went a bit further.

They verbally agreed by handshake, reporters said, that Holden would spend the rest of the month of January on his utility beat.

But the deal broke down after Holden appeared on a television news show the same night he turned in an article about CEI. The article was not printed but ran later without his byline.

The Guild had been outmaneuvered. The written agreement, made in a bar with both sides drinking, said nothing of Holden returning to his beat.

Holden resigned in disgust.

His demise became a fulfillment of a warning made by a CEI public relation person more than a year before. The CEI spokesperson told Holden:

“CEI will be here long after Bob Holden is gone.”

However, Holden’s refusal to be censored and the reporters’ protests damaged the PD’s credibility. It put the newspaper in a vulnerable position. No newspaper wants to be seen as openly censoring itself.

Editors were forced to assign others to write the history of the dispute that led to the ballot issue.

The situation made it difficult for the PD to censor a second time. A team of reporters was assigned to the story.

The paper had no choice but to accept the articles the new team wrote after Holden’s resignation. The news room was in insurrection mode.

“We’d have gone crazy and we’d have gone crazy in public,” said one reporter asked what might have happened had the PD tried censorship again.

“The Saturday Night Massacre would apply,” he said, referring to the resignations during Watergate. It would have put the PD in the position of having no reporter who would take the assignment.

Dave Abbott, now head of the Gund Foundation and Dan Biddle, who became a Pulitzer Prize winner in Philadelphia, were assigned to write the series. Their articles revealed the hidden truth about how CEI tried to damage the city’s electric system. One headline on Feb. 11 revealed the tone: “CEI Objective: Snuff Muny Light.

The dramatic outcome of this battle between staff and management was revealed by the result of the vote. It flipped.

The early poll showed that Cleveland voters would elect to sell the city’s electric system to CEI by a two to one vote.

The dispute and Holden’s resignation allowed freedom to the two new reporters. Prompted by revelations they produced, the actual vote came in two to one to maintain the city’s electric power system.

It was a critical example of the power of information. It revealed that if you give people the truth, they’ll understand and make their decision. It also shows that when the news media hide the truth it distorts democratic decision-making.

The change in public attitude was striking.

I wrote in Point of View before the election: “The virtual blackout on Muny Light has been shattered. The Holden affair and the entry of Ralph Nader into the fight gave focus to the charges of the news media’s refusal to focus on the dispute in a meaningful way. The news media here were open to the charges of serious distortion of the news.

“But in the past week, the coverage in both the Press and PD broke the blackout and silence. Finally, in a realistic manner information has begun to flow.

“Whether it will be enough to offset the years of distortion and failure to report will be revealed by the vote.”

It was a game changer. The voters spoke decisively. The city retained its system. And does to this day.

Holden later left town to pursue an academic career. Today he is Dr. Holden, a tenured professor of Latin American history at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va.

In a recent interview he called that period in Cleveland, “A special time, a different time.”

He recalled that he somehow learned about the anti-trust charges by the city against CEI. It shocked him that the Plain Dealer hadn’t covered the issue. “We haven’t covered this,” he said he complained to editors. “How could we have missed this?” he asked them. Holden started to make telephone calls and cover it.

Actually, it wasn’t that much of a secret.

Two years before in 1977 I wrote a piece entitled: “U. S. Ruling Puts CEI in Jeopardy of Losing $325 Million Anti-trust Suit to Muny Light. Perk, Forbes Trying to Boot Away Opportunity.”

Here’s how I put it: “There’s a robbery in progress with the mayor of Cleveland, the Council President and the Cleveland news media accessories before the fact.

“The Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI) is still trying to STEAL Cleveland’s electric light plant (MUNY) from the city.

“The mayor knows it. The Council President knows it. The news media know it. And the public should know it.”

Holden now can’t remember how he discovered the anti-trust problem but says it may have been from Point of View, where the above appeared.

Ironically, Holden, after he left the Plain Dealer, went to work for Kucinich. He said he was assigned to the community relations department but actually he was a speech writer for the Mayor.

Holden, as a number of other progressives, became disenchanted with Kucinich during his re-election campaign. They particularly soured because of his use of racial politics as Kucinich tried to retain office. He lost in 1979 to George Voinovich.

The crucial issue of the ideological desire of CEI to rid itself of competition by a public agency was far from over. It was to play out in two federal court anti-trust trials.

The first trial ended in a hung jury as one juror held out in CEI’s favor. The city lost the second anti-trust trial.

But Holden proved an old adage that one man can make a difference.

Given the truth, the public also made a difference.

Books We Suggest

Dr. John J. Grabowski

Dr. John J. Grabowski holds a joint position as the Krieger-Mueller Historian and Vice President for Collections at the Western Reserve Historical Society and the Krieger-Mueller Associate Professor of Applied History at Case Western Reserve University.

Cleveland: A Concise History (Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1996) Carol Poh Miller, Robert Wheeler

The Birth of Modern Cleveland 1865-1930 (Miggins and Campbell, eds.) (The Western Reserve Historical Society publication) 1988

Identity, Conflict, and Cooperation: Central Europeans in Cleveland, 1850-1930 David C. Hammack (Editor), Diane L. Grabowski (Editor), John J. Grabowski (Editor) 2002

Alabama North

AlabamaNorth: African-American Migrants, Community, and Working-Class Activism in Cleveland, 1915-1945 Kimberley L. Phillips 1999

Cleveland: A Tradition of Reform

by David D. Van Tassel and John Grabowski 1986

Greg Deegan – Teacher Beachwood High School and Director of Teaching Cleveland Institute

A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870 – 1930, by Kenneth L. Kusmer 1978

Cleveland: The Best Kept Secret, by George Condon 1967

Horse Trails to Regional Rails: The Story of Public Transit in Greater Cleveland, by James A. Toman and Blaine S. Hayes 1996

Tom Suddes – Professor of Journalism Ohio University/Practicing Journalist

The Western Reserve; the Story of New Connecticut in Ohio. Hatcher, Harlan. (Indianapolis, 1949)

The Confessions of a Reformer. Howe, Frederic C. (New York, 1925) (Frederick Howe link is here) (Tom L. Johnson chapter is here)

Point of View [newsletter]. (Cleveland, 1968 – ). Edited by Roldo Bartimole.

The Life of Mr. Justice Clarke: A Testament to the Power of Liberal Dissent in America. Warner, Hoyt L. (Cleveland, 1959)

Progressivism in Ohio, 1897-1917. Warner, Hoyt L. (Columbus, 1964)

Roldo Bartimole – Journalist

My Story. Tom L. Johnson, edited by Elizabeth J. Hauser 1912 (Tom L. Johnson link is here)

Promises of Power. Carl Stokes 1973

The Confessions of a Reformer. Frederic C. Howe. 1925 Tom L. Johnson chapter is here. Marcus Hanna chapter is here.

Silent Syndicate. Hank Messick 1967

They Call it a Game. by Bernie Parrish, former Cleveland Browns football player and someone who is still fighting for old time players. (for sports fans a real inside look about pro football with a special look at Art Modell & Browns) 1971

More lists on the way

“Mark Hanna’s 1898 Senate Bribery Scandal” by Kristie Miller and Robert H. McGIinnis

Mark Hanna’s 1898 Senate Bribery Scandal

KRISTIE MILLER and ROBERT H. McGINNIS

One enduring question about Mark Hanna is if he paid a bribe during his 1898 Senate campaign. This essay offers the analysis of the authors

Karamu House from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

KARAMU HOUSE is a neighborhood settlement that became nationally known for its dedication to interracial theater and the arts. It was founded as the Neighborhood Assn. at 2239 E. 38th St. in 1915 by 2 young white social workers, ROWENA† and RUSSELL JELLIFFE†, with the support of the Second Presbyterian Church, but it soon was popularly known as the Playhouse Settlement. As an entry into community life, the Jelliffes began producing plays with interracial casts in 1917. Their affiliation with the church ended in 1919, when they incorporated as the Neighborhood Assn. In 1920 they sponsored the Dumas Dramatic Club, which was renamed the Gilpin Players, after the noted black actor Charles Gilpin in 1922. A theater was acquired adjacent to the settlement in 1927 and named “Karamu,” Swahili for “a place of joyful meeting,” a name adopted by the entire settlement in 1941. In the 1930s the Gilpin Players established a collaboration with Karamu alumnus LANGSTON HUGHES†, giving premieres of several of his plays. In 1940 a modern dance troupe from Karamu trained by Marjorie Witt Johnson won the praise of Lifemagazine for its appearance at the New York World’s Fair. Following a fire which destroyed the theater in 1939, Karamu was eventually rebuilt in 1949, through the aid of LEONARD HANNA, JR.†, and the Rockefeller Foundation as a 2-theater complex at E. 89th and Quincy. Facilities were also provided for Karamu’s noteworthy programs and classes in dancing and the visual arts. Led in the 1950s by such professional staff members as Benno Frank and Reuben Silver, Karamu gained a reputation as one of the best amateur groups in the country. With the rise of Black Nationalism in the 1970s, however, it embarked upon a controversial course which promoted theatrical presentations primarily by blacks about the black experience and its attempt to form a professional acting company in 1982 proved unsuccessful. In 1980 Marjorie Witt Johnson, together with Karamu artistic director Linda Thomas Jones, founded the Imani African American Dance Co., a troupe which danced to African drum beats, reminiscent of the original Karamu Dancers.

With the appointment of Margaret Ford-Taylor as executive director in 1988, Karamu attempted to return to its multicultural roots as a metropolitan center for all races while fulfilling its “unique responsibility” for the development of black artists. The Karamu’s Drama/Theater for Youth Project was cited for excellence by the Ohio Alliance for Arts Education in 1991 and in 1993 it won the first annual Anne Flagg Award given by the American Alliance of Theater in Education honoring outstanding work in the promotion of multicultural understanding. In May 1994 Karamu joined with BANK ONE to open the Karamu Community Banking Center within the Karamu complex.

As a community-based nonprofit arts and education institution, Karamu House has maintained its historic commitment to encouraging and supporting the preservation, celebration, and evolution of African-American culture. As a cultural institution, Karamu presented a regular yearly schedule of six plays ranging from serious dramatic plays to musical, and as an educational one, it provided classes in drama, dance, music, and art in conjunction with before- and after-school programming with acting instruction for youth. In 2008, the Department of Jusice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention awarded Karamu House $170,000 to increase digital arts classes for children who do not receive computer training at school.

Over its ninety years history, Karamu has cultivated a well-deserved reputation for nurturing African American actors. Among notable performers who refined their craft at Karamu and later found success on Broadway, in Hollywood, and at stages and concert halls throughout the world were Ruby Dee, Ron O’Neal, Robert Guillaume, and Imani Hakim. One of the most treasured of Karamu’s productions was the annual holiday presentation of “Black Nativity,” a play by LANGSTON HUGHES†. It also hosted an annual free Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration and encouraged a candid public discussion of relevant issues in “talk-back sessions” preceding select performances.

In 2009, Karamu House boasted three performing halls: 215-seat Jelliffe Theatre, 100-seat Arena Theatre, and 90-seat Anne Mae’s Theatre. It also operated a day care facility, a summer camp, and a community outreach program. Gregory Ashe, the former president of Boys and Girls Clubs of Cleveland, served as the executive director of Karamu House since 2007 and Terrence Spivey as the artistic director of the venerable organization since 2003.

Karamu House Records, WRHS

Russell and Rowena Jelliffe Papers, WRHS

Selby, John. Beyond Civil Rights (1966)

Last Modified: 04 Oct 2009 02:08:09 PM

Teaching Cleveland Journalism Hall of Fame

History of Ohio Steelmaking

History of Ohio Steelmaking

From the Ohio Steel Council

THE HISTORY OF STEEL IN OHIO

Ohio has a proud tradition of steelmaking. Its access to the Great Lakes, network of navigable rivers, and rich deposits of coal and iron literally helped to build a nation.

Ohio‘s iron and steelmaking roots go back to 1802, the same year the state was admitted to the Union. In this year, the first blast furnace west of the Alleghenies was erected in Poland Township, near Youngstown. It averaged only two tons of iron a day.

During the first decades of the 19th century, ironmaking was a decentralized activity throughout the state. The abundance of low-grade iron ore in many regions of Ohio made the establishment of iron furnaces a relatively common occurrence, and there was a ready demand for the product by local blacksmiths, who turned the pig iron into farm and home utensils. Early furnaces used charcoal as fuel.

By mid-century, however, the picture had changed. The location of ironmaking furnaces became concentrated in southern Ohio, in Vinton, Jackson, Sciota and Lawrence counties. Of the 48 blast furnaces operating in the state at the time, 35 were located in this region. A secondary concentration of nine furnaces was found in the Mahoning Valley.

The iron industry had slowly switched its fuel source from charcoal to coke, a purified form of bituminous coal. The burning coke, when exposed to blasts of air (hence the name “blast furnace”), creates the high temperatures needed to melt iron ore for processing into ingots. These ingots originally were named “pigs” because of the molds’ resemblance to nursing piglets, and the name has stuck ever since.

Deposits of block coal, discovered near Youngstown in 1845, could be used in iron furnaces without being converted to coke. These coal deposits were a major catalyst for the growth of the iron industry in northeastern Ohio.

In 1850, Ohio was essentially rural, even though its major metropolis, Cincinnati, had become the nation’s third most important manufacturing city. But in these changing years, the roar of machinery and the smoke of the factory announced the coming of the Industrial Revolution. Cities grew, and railroads reached to the most isolated counties. Cincinnati, not well located with respect to iron ore and coke, watched as places like Akron and Cleveland became the industrial cities of the future. By 1853, Cleveland had rail connections with most eastern cities as well as with Cincinnati and Chicago. This technological advancement, combined with its coal and iron ore resources, transformed Cleveland into the third-largest iron and steel city in the country.

Yet, by 1880, more significant for the state’s industrial future was the rapid growth of little cities in the Cuyahoga and Mahoning valleys, like Akron, Canton and Youngstown. The Mahoning Valley was becoming one of the great iron and steel areas of the nation. Youngstown was a convenient meeting place for individuals looking for ore and coke. The first of the modern iron-clad blast furnaces was erected in Struthers in 1871, greatly expanding production.

The nation’s westward expansion increased demand for iron and guaranteed that Ohio’s iron furnaces would stay busy. Within the next decade, however, processes became widely available to produce large quantities of a new, superior product – steel. Steel is stronger and more flexible, making it better suited than iron for rails, beams and other products. The building of a vast national rail system after the Civil War made steel much more valuable than iron.

Ohio continued to be a pioneer in this emerging steel industry. The first Bessemer converter – the new device for steel manufacturers – was purchased by the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company, which eventually was absorbed by U.S. Steel Corporation. In 1875, the first open-hearth furnace built exclusively for the production of steel was constructed by the Otis Steel Company in Cleveland, which became Jones & Laughlin Steel Company in 1942. During the 1870s and continuing into the 1880s, steel replaced iron as the primary metal produced in Ohio. By 1892, Ohio ranked as the second-largest steel-producing state behind Pennsylvania.

In 1901, open-hearth furnaces began to overtake Bessemer converters as the primary method of making steel. The molten steel was poured into ingots, which were fabricated into rails, bars, wire, pipes, plates and sheets. Also, steel was structurally shaped in specialized rolling mills, often in separate establishments or forge shops.

Most steel companies in 1901 were not completely integrated, a term used to describe a steel producer that has ironmaking and steelmaking capabilities and can process finished and semi-finished steel products. Many companies operated only blast furnaces and sold their pig iron on the open market. Others combined ironmaking and steelmaking capabilities, but supplied fabricators that produced a single range of finished products.

The formation of the United States Steel Corporation in February 1901 capped a merger wave in the 1890s. In Ohio, mergers included the creation of Republic Iron and Steel Company, a “rolling mill trust” formed by combining 34 small companies in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Alabama.

U.S. Steel, created by combining J.P. Morgan’s Federal Steel with Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Steel, was the first billion-dollar company in American corporate history. It consisted of eight major and many smaller firms and some 200 plants. The situation forced competitors to build or acquire mills and mines in order to become integrated steelmakers.

Armco also began integrating in this period, incorporating in 1899 as the American Rolling Mill Company of Middletown, Ohio. Youngstown Sheet & Tube was created in late 1900, with the vision of a large, integrated steel producer.

In 1910, Elbert Gary, who ran U.S. Steel, redefined the goals, behavior and attitudes of the steel industry. Fears of antitrust action by the government in response to U.S. Steel’s stranglehold on the market led to a search for stability. One of these elements was a pricing formula that eliminated the advantages of geography. This and other initiatives of Gary – and the American Iron and Steel Institute, which he formed – helped Ohio steel to remain competitive.

Within Ohio, the Mahoning Valley was the leading pig iron production region, with 39 percent of the Ohio total and 9 percent of the national total in 1920.

Like other American industries, Ohio steel was devastated by the Great Depression. Markets shrunk precipitously, except for light-rolled sheet products used in automobiles and home appliances. This shift hit producers of primarily heavy structural shapes, like pipe and rails, especially hard.

Youngstown Sheet & Tube was poorly situated in the light flat-rolled market because it had delayed improvements during the 1920s. The company did not build hot-strip mills until 1935 and 1939, and it struggled through the decade. Armco struggled against geography, paying higher transportation costs for ore and coal because its Marion mill was not located on the lakes or the Ohio River. However, Armco at least was strong in light-rolled steel. Another asset was its research laboratory, which introduced a new galvanizing technique in 1937 that permitted shaping the steel after the tin coating had been applied.

Republic Steel shared Armco’s disadvantages, but managed to do better because of the company’s light-steel capacity. After 1935, Republic’s management turned aggressive and acquired several new firms.

Ohio remained one of the major focal points of the steel industry. Most of the national steel corporations operated facilities in Ohio during the 1930-1970 period. These included Armco, Cyclops, Jones & Laughlin, National, Pittsburgh, Republic, Sharon, U.S. Steel, Wheeling and Youngstown Sheet & Tube. Three of these firms – Armco, Republic and Youngstown Sheet & Tube – had their national corporate headquarters in Ohio.

THE STEEL INDUSTRY AT WAR (1940-45)

One of the more amazing chapters in American industrial history was the performance of the steel industry during World War II. Firms that had struggled through the Depression operated at full capacity by 1942. Several major steel producers actually exceeded average annual capacities as the industry set new production records. Republic Steel hit 100.4 percent of its capacity in 1942. As a whole, the American steel industry produced almost 90 million tons of finished steel during the peak year of 1944, and 427 million tons from 1941 through 1945.

Equally significant, however, was the opportunity that the steel industry faced in the immediate postwar period. U.S. producers had no real rivals and enjoyed unprecedented superiority. Almost two-thirds of the world’s steel production in 1945 came from the United States. Because steelmakers confronted so few competitors in world markets, quantity became the driving concern. The industry’s self-assurance also manifested itself in a reluctance to invest in innovation and new technology.

But many of the roots of steel’s later problems were not created by the industry itself. American mills located in the Ohio and Mahoning river valleys paid the penalty of higher transportation costs compared to mills on the Great Lakes. Government policies were also partly responsible for the industry’s later problems. When the country did not sink back into depression after the war, steel executives hoped to discard wartime controls quickly. The government did not agree.

Nevertheless, a massive steel expansion program in the 1950s pushed capacity from 100 million ingot-tons in 1950 to 148.5 million in 1960. The revenue from this increase mostly bought existing technology for established plants. Blast furnaces grew taller and output was increased. Ohio companies followed this trend.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES, NEW COMPETITORS

Two new technologies pioneered in the 1950s were the basic oxygen process and the continuous caster. Both innovations offered major economic benefits over existing processes. The basic oxygen furnace (BOF) uses a process that injects oxygen from the top into a vessel filled with molten iron and scrap, producing steel much more quickly than an open-hearth furnace. Continuous casting developed more slowly. Traditionally, steel ingots were transformed into shapes in several steps – first rolled into slabs or blooms, which were then rolled into beams, bars, pipe, wire, plates or sheets. A continuous caster produces slabs, blooms or billets directly from molten steel, saving time and energy. Republic Steel explored this process as early as the mid-1940s. But the industry as a whole was cautious and slow to integrate new technology, uncertain about the viability of the new procedures.

Smaller companies moved first to install both of these key innovations. “Big Steel,” for the most part, waited until the technologies were better developed. For oxygen furnaces, this had happened by 1963; continuous casting was proved by the end of the decade. In 1968, the first vertical caster in Ohio was constructed at Republic Steel in Canton.

The combination of limited profits, intense pressure for new technology and less-than-optimal installations was dangerous enough. But two other developments further complicated the Ohio steel picture. Foreign competitors began shipping significant quantities of steel to the United States. Imports rose from 5.4 million tons in 1963 to 18 million tons in 1968. This flood of imported steel prevented the industry from earning the capital necessary for investments in modernization.

In addition, another competitor had appeared on the domestic scene: the mini-mill. Initially, mini-mills were facilities with electric furnaces that melted scrap and produced up to 250,000 tons of steel a year. But the technological developments of the 1960s opened other avenues for enterprising small firms. By adding continuous casters and small bar mills to the electric furnaces, the mini-mills could produce reinforcing rods, small diameter bars and angles far less expensively than large firms could, using traditional technology.

The mid-1970s and early 1980s represented a period of substantial change. Through the 1970s, the industry struggled. It has been argued that excessive wage hikes were a central factor in the loss of competitiveness by American steel. Certainly, foreign competitors had the advantage of cheaper labor. They also, in many cases, had more modern, efficient facilities than their U.S. counterparts. But foreign companies were often subsidized by their governments. In addition, foreign-produced finished consumer products made from steel were being imported at a substantial increase, which shut out a market that had been open to U.S. producers. Finally, the period saw the introduction of new materials that served as substitutes for steel – namely aluminum, plastic and composites.

Voluntary import restrictions worked for a few years; but, after 1973, a surge in demand permitted foreign industry to ignore the system. And in 1977, imported steel totaled 21 million tons.

U.S. steel found its production capacity well beyond the demand for domestic steel. Consequently, the most inefficient mills were closed. Mergers of existing firms took place, and new investors entered the industry to purchase selected operations. In 1977, Youngstown Sheet & Tube was merged with Jones & Laughlin Steel Company, a harbinger of things to come.

Double-digit inflation hit the industry hard. However, the problems of the 1970s paled against the difficulties caused by a recession in 1982. In 1975, 20 fully integrated steel companies operated 47 full-scale mills. By 1985, only 14 companies remained, with 23 mills.

During the 1980s, both employment and raw steel production in Ohio fell to roughly one-half their respective highest years of the 1970s. However, new investment continued, a trend that continued in the 1990s and paid off handsomely in increases in Ohio employment and production.

Today’s Ohio steel industry has undergone more than 30 years of restructuring. During this period, many companies have closed or merged with other companies; union contracts and work rules have been revamped; and new technologies have been introduced as a result of millions of dollars that steel companies have invested in their facilities.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Ohio mills invested in quality and cost improvement. During this period, the industry began reaping the benefits of increased continuous casting capabilities, high-tech galvanizing lines, revamped hot-strip mills and continuous processing lines.

By the late 1980s, the news media was reporting exciting rejuvenation in the industry. In the 1990s, the steel market was stronger than it had been in decades.

However, at the dawn of the 21st century, the steel industry again faced significant challenges. The most recent period of upheaval occurred between 1998 and 2003 when, in the wake of a flood of unfairly traded steel imports from Asia, Russia and Brazil, many companies were forced into bankruptcy and many steelworkers were laid off.

In response to this crisis, the steel industry consolidated and union contracts were renegotiated to allow greater flexibility in response to trends in the market place.

Today, steelworkers are trained to work in a number of positions, and they have greater latitude and authority in responding to the needs of the steelmaking facility. In addition, there are fewer steel companies in the U.S., which enables the industry to respond swiftly to market changes. Larger companies are able to shift resources from one operation to the next quickly and efficiently in response to demand. At the same time, smaller steel companies still do very well by focusing on niche markets and specialties.

As a result of these changes, Ohio’s revitalized steel industry has returned to profitability. In fact, Ohio steel companies today produce as much steel as they did before the imports crisis of 1998, even though they employ fewer people. Technology and a more versatile and highly skilled workforce have made up the difference.

Warszawa: The Development of a Polish-American Industrial Community 1882-1919

From Cleveland State

WARSZAWA:

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POLISH-AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL COMMUNITY, 1882-1919

Chuck Kaczynski

On the morning of 3 June 1882 the Cleveland Leader ran a copy of a notice that had been posted by the president of the Cleveland Rolling Mill regarding the condition of the plant in light of the on going strike.

Cleveland Rolling Mill Company

Cleveland, O., June 2, 1882.

On Monday next, the wire mill, rail mill, new

melting furnace, and blooming mill will start

with non-union men, single turn. As soon as

practicable other departments will start, due

notice of which will be given.

(Signed) William Chisholm, President.

A large number of the men referred to by Chisholm were recent Polish immigrants who would come to settle in the area northwest of the rolling mill. Thirty seven years later, in the Fall of 1919, the Cleveland Rolling Mill was again hit by a major strike. By this time, however, Polish-American workings composed approximately fifty percent of the strikers who walked out in support of the twelve point demands of the Amalgamated Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers Association. What caused this shift?

This paper examines the causes of this change in attitude and the growing sense of permanency among the employees of the Cleveland Rolling Mill and their families. In order to understand this transition, one must examine the development of the Polish-American community of Warszawa, located on the southeast side of Cleveland, which experienced a fantastic rate of growth between the years 1882 and 1919. By examining this growth one can identify a shift in attitude among the Polish immigrants from viewing themselves as a temporary “colony” of migrants to a permanent “community” of Polish-American workers. It is this attitudinal evolution which accounts for this transition from strike breakers to strikers.

A number of factors are examined in this paper which illustrate this transition. Primary among these is the development of Saint Stanislaus parish which acted as a center of the community. A statistical analysis of baptisms, marriages, societies and confraternities, and school size illustrates the rate of growth of the Warszawa community. Along with this, the paper examines the development of mutual aid societies, savings and loans and banks, which supported the growing permanency among the residents of Warszawa.

The history of Poles in Cleveland can be traced back to 1848. Through the 1870’s the Polish population of Cleveland was composed primarily of skilled artisans who were either self-employed or employed for wages in small manufacturing plants. At this time, Cleveland’s Poles lived among the Czech community centered around Croton Avenue, three miles north of the Cleveland Rolling Mill. But, with the increasing number of Poles coming to Cleveland, a new settlement was sought. In the late 1870’s between seventy and eighty families left the Croton Avenue community and settled in farmland near the intersection of Fleet Avenue and Tod Street. It would be from this nucleus that the Warszawa community would grow. Along with their personal belongings, the Poles who moved to Warszawa brought with them a Roman Catholic parish, Saint Stanislaus, which had been created by the Cleveland Diocese in 1873. Lacking a permanent location, this community held its services at Saint Mary’s Church in Cleveland’s “Flats” district.

During the late 1870’s and early 1880’s, the Poles of Warszawa came to rely on the Cleveland Rolling Mill for a majority of their jobs. The Cleveland Rolling Mill was part of an industry which had existed in Cleveland since 1856. With the increased demand for iron resulting from the American Civil War, the Cleveland Rolling Mill hired a number of Czechs and Poles to bolster the output of the existing Welsh/Irish work force. Through the 1880’s, the Poles and Czechs came to fill a number of unskilled and semiskilled positions at the mill.