From the Cleveland Plain Dealer on the 40th Anniversary of Carl Stokes election as mayor of Cleveland.

The link is here

The man, the strategy and the seismic shift

11/04/07

Brent Larkin

Plain Dealer Reporter

By midnight, all seemed lost. And the mood inside Carl B. Stokes’ downtown headquarters had turned decidedly gloomy.

Destiny was about to deny Stokes what he wanted most to be the first black elected mayor of a major American city.

With 70 percent of the vote counted, Republican Seth Taft had built what seemed an insurmountable lead. As Election Day turned to Wednesday, Taft had pulled in front by 20,000 votes.

It seemed that Stokes, a 40-year-old state representative who had handily defeated incumbent Mayor Ralph Locher in the Democratic primary, would lose the general election to a Republican in a city with a minuscule Republican population.

Cleveland Press reporter Dick Feagler would write that women wept during this tense, trying period when defeat seemed certain.

A Dixieland band played ‘S’Wonderful,’ but it wasn’t, described Feagler, adding that for four hours it appeared Seth Taft had won.

There was really a sense of despair, recalled Anne Bloomberg, at the time a 26-year-old civil rights activist and campaign volunteer. Our hopes were so high going in, and it looked like it would all be for naught.

But then it all began to change. Votes from predominantly black, East Side neighborhoods were the last to be counted. Slowly, but inexorably, Taft’s lead began to shrink.

We had ward-watchers in the neighborhoods and we knew Carl would come back, recalled Ann Felber Kiggen, Stokes’ campaign scheduler. When it began to happen, I remember this incredible feeling that swept through the headquarters. People were dancing and holding hands. It was uncontained joy.

It was 3 a.m. when, with nearly 900 of the city’s 903 precincts reporting, Stokes took the lead for the first time. Out of 250,000 votes cast, he won by 2,500.

Then, as the mayor-elect appeared before about 400 jubilant supports, the room grew quiet when he declared, I can say to all of you that never before have I known the full meaning of the words, ‘God Bless America.’

In his autobiography, Promises of Power, Stokes would later marvel at the magnitude of what happened that night.

In a race for high office, the grandson of a slave had defeated the grandson of a president.

That had never happened before. And it hasn’t happened since.

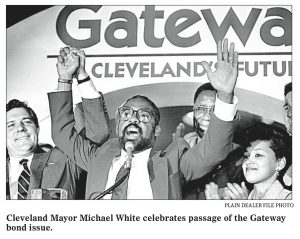

The Cleveland that elected Carl B. Stokes mayor was a far cry from the one that chose Michael R. White as the city’s second black mayor 22 years later and light years removed from the one that elected Frank Jackson in 2005.

In 1967, Cleveland was still a top-10 city, with a population north of 750,000 nearly 300,000 more than today. Because race was as much a factor in city politics then as it is now, Stokes’ election was all the more remarkable; the city’s black population was only about 35 percent then. Today, that figure surpasses 53 percent.

To defeat Seth Taft, a decent man with a magic name who would later serve with distinction as a Cuyahoga County commissioner, Stokes needed white votes lots of them.

We knew we had to broaden our base on the west and south sides, recalled Charlie Butts, Stokes’ brainy, 25-year-old campaign manager fresh out of Oberlin College. But we had to be careful not to give the appearance of running different campaigns in different parts of town.

To give his campaign legitimacy, Stokes desperately needed support from whites in corporate boardrooms and city neighborhoods. He got it from this newspaper, which endorsed him on the front page.

He got it from people like Bob Bry, a vice president of Otis Elevator who organized a group of business leaders to take out newspaper ads on Stokes’ behalf.

I was a registered Republican, but my sympathies were with what Carl was trying to do, said Bry, now 84 and living in Florida. Some business leaders were bothered by it. But no one ever said anything to my face.

He got it from people like Ann and Joe McManamon and hundreds of others like them who paid a price for welcoming Stokes into their living rooms and churches.

There were recriminations, remembered Ann McManamon. We got some very hateful phone calls. It got quite nasty. But our friends stuck with us and were supportive.

Nearly one in five whites voted for Stokes which meant he needed nearly nine out of every 10 black votes.

To win those votes, Stokes built a political organization that, to this day, serves as a model for black candidates across the country. It was a base that relied heavily on churches, ward leaders and a grass-roots field operation that extensively schooled street captains on how to maximize turnout.

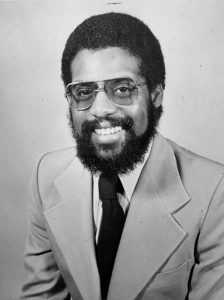

That same base later enabled Stokes’ brother, Lou, to become an institution in Congress. It helped make former City Council President George Forbes powerful and wealthy. And it twice brought Arnold Pinkney to the brink of becoming Cleveland’s second black mayor.

It was a base built to last and last it did.

All around the country in places like Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia and Chicago black candidates copied what Carl was able to achieve in Cleveland, said his brother. What made it special was that it was done so well and had never been done before.

There was no blueprint for electing a black mayor of a major American city. So Stokes drew his own.

He had a plan on how to win, and he never strayed from it, said Forbes. In his prime, there was none better none.

From City Hall to New York, and, finally, back home

Stokes won re-election in 1969, but did not seek a third term in 1971, leaving soon after for New York, where he was a television anchor and later a reporter for NBC. Over the years, Stokes gave various reasons for his decision not to seek a third term, but he was clearly tired of the constant struggles involved in leading a big city with mounting problems.

Stokes’ record as mayor was decidedly mixed. He brought a sense of fairness to the city’s hiring practices, helped raise the level of social services and aggressively fought to improve housing conditions. But Stokes fought repeatedly with City Council, and revelations that some funds from a poverty-fighting program he founded went to nationalists involved in the killing of police in the Glenville riots significantly eroded his popularity.

Upon his return to Cleveland in 1980, Stokes found that the new political stars were his brother and Forbes. In 1983, he became a Municipal Court judge an important position that lacked the high profile of a powerful congressman and council president. There were also some troubling and embarrassing moments. Stokes engaged in some high-profile political fights with onetime allies and was twice accused of shoplifting he paid restitution on one charge and was acquited of another.

But none of what happened later detracts from the significance of what Stokes achieved in 1967.

Many black leaders in the ’60s aspired to be Cleveland’s mayor, but only one ever stood a chance.

Only one person could have built that base, said Pinkney. Only one person had the charisma, the experience and the drive to win. Back then, it took a special talent for a black to be elected mayor. And only Carl had that talent.

Stokes was not a civil rights leader. He was a politician. And four decades later, Pinkney and others still speak with a sense of awe of Stokes’ political gifts. Butts thinks Stokes was born with an intellect, understanding and chemistry that allowed him to connect to voters in ways almost unprecedented. Forbes volunteers that Stokes had the whole package looks, the charm and one of the sharpest political minds I’ve ever seen. Kiggen says he was the most charismatic man anyone could hope to ever meet.

In his book, Stokes wrote that he considered the 1965 campaign for mayor, in which he narrowly lost to Locher in the Democratic primary, the high point of my career.

He was mistaken. The 1965 campaign energized Stokes’ base. And it set the table for what would follow. But it paled, compared to what would happen two years later.

Always looking ahead, even at the end

For all his winning ways, Stokes was also the most complex politician I ever dealt with. He could be warm and witty one day, your enemy the next.

On Jan. 30, 1996, we visited over lunch at an East Side restaurant. He knew by then that his fight with cancer of the esophagus was one he couldn’t win.

As Stokes picked at food he could barely swallow, he spoke with no rancor as he reminisced about those days of glory that landed him on the cover of Time magazine. He wasn’t finished looking ahead, either: He eagerly agreed to meet with a group of young journalists at this newspaper to talk about how the political process affects minorities, and we chose a date in February.

But when the day came, he was too ill. By early April, he was gone.

He had long before kept the date that mattered most, though. That was the one back in 1967 that made him, in the sense of history, immortal.