Samuel Andrews arrived in Cleveland in 1857 and helped oil supplier Charles Dean’s company become the first to refine kerosene from petroleum. In 1863, he co-founded Andrews, Clark & Co., which became Standard Oil Co. Andrews went on to fund local education institutions, such as Brooks Military School.

Samuel Austin built The Austin Co. into one of the largest construction firms in the United States. In 1911, Austin constructed a research facility in East Cleveland — the core of today’s Nela Park. With help from the Ford Motor Co., Austin designed and built a $60 million, 600-acre factory in the Soviet Union.

Newton D. Baker came to Cleveland in 1899 and was eventually elected mayor in 1911, a title he held for two terms. Baker was also a confidant of President Woodrow Wilson and secretary of the war in 1916. Baker returned to Cleveland and founded the law firm known today as Baker & Hostetler LLP.

In 13 years as managing partner at Ernst & Ernst (now Ernst & Young), Richard T. Baker pushed the firm to achieve a national presence with 135 offices. He also served on the boards of directors for companies such as Anheuser-Busch Cos. Inc., General Electric Co., and the National Broadcasting Co.

Louis D. Beaumont and his brother-in-law, Col. David May, bought Cleveland’s E.R. Hull & Dutton Co. in 1899. Beaumont transformed the store into the May Co. and it went on to become the nation’s largest retail department-store chain.

From 1959, Jess Bell led his father Jesse G. Bell’s company, Bonne Bell Inc., to become one of the country’s top cosmetics manufacturers. Jess Bell is also known for his healthy lifestyle, a value reflected in his company, which offers in-house fitness centers and incentives to employees who exercise regularly, lose weight or quit smoking.

In 1912, Leon A. Beeghly formed the New York-based Buffalo Slag Co. whose blast-furnace slag was widely used in highway construction. Two years later, he opened Standard Slag Co. in Youngstown, which grew rapidly and expanded to 25 plants. Despite the Depression, Standard Slag grew, acquiring sand plants and limestone quarries.

In 1928, Italian-born Hector Boiardi sold packaged takeout dinners from his restaurant, Giardino d’Italia, near East Ninth Street. Despite the Depression, Boiardi’s operation outgrew three processing plants. As a marketing strategy, he spelled his name phonetically, making Chef Boy-ar-dee a household name.

Alva “Ted” Bonda returned from the U.S. Army in the mid-1940s and accepted a request that he manage an Avis Rent-a-Car franchise. Bonda became national chairman of the rental-car giant in 1968. He left to run the Airport Parking Co. of America (APCOA). By the time APCOA was sold in the late 1980s, it was the largest such company in the world.

In 1853, Alva Bradley and Ahira Cobb founded the shipyards of Bradley & Cobb on the Vermillion River. Bradley moved to Cleveland in 1859 and bought out Cobb. The business, later known as Cleveland & Buffalo Transit Co., amassed a fleet that captured much of the early iron-ore shipping on the Great Lakes.

Joseph M. Bruening’s company, Bearings Inc., distributed antifriction bearings and power-transmission components and built its success on commitment to service. By 1977, the company’s annual sales reached $200 million and eventually went on to become the largest bearings distributor in the world.

In 1879, Charles F. Brush improved electric arc lights with his patented open-coil dynamo (a precursor to the modern generator), making Cleveland the first city in the world to illuminate its streets extensively with electric lights.

H. Peter Burg began his career at FirstEnergy Corp. (then Ohio Edison) as a financial analyst trainee in 1968 and quickly moved up the ranks, serving as treasurer, vice president, senior vice president, and president and COO in 1996. He was named president and chairman in 1999.

As Cleveland’s first permanent pioneer, Lorenzo Carter settled near the riverbank in 1797 and became the city’s first leader, innkeeper, shipbuilder and policeman. Carter bought lots from the Connecticut Land Co. and by 1802, he owned much of what is now the East Bank of the Flats.

Part banker, part real estate mogul, in the mid-1800s, Leonard Case Sr. led efforts to move a medical college from Willoughby to Cleveland and helped launch Cleveland University. After Case’s death, his son, Leonard Jr., donated $1 million to found the Case School of Applied Science, now part of Case Western Reserve University.

Henry Chisholm helped establish Cleveland’s reputation as a steel leader. After working for the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad in the 1850s, he joined Jones & Co., which rolled iron rails. He served as an investor and later as manager and president. The firm, renamed Cleveland Rolling Mill, introduced the Bessemer furnace.

Moses Cleaveland ventured to the mouth of the Cuyahoga River on July 22, 1796. As director of the Connecticut Land Co., Cleaveland led the first surveying expedition of the company’s newly acquired property. A lawyer by trade, Cleaveland served in the Connecticut legislature and was also a general in the Connecticut militia.

After working for the Cleveland Iron Co., Jacob D. Cox Sr. entered a partnership with C.C. Newton in 1876 and began manufacturing the twist drill in Dunkirk, N.Y. He moved the company to Cleveland where it become a major part of the city’s industrial economy.

Frederick C. Crawford began working at Steel Products Co. sorting scrap for only 35 cents an hour. By 1933, he was president of the company, renamed Thompson Products Inc. (now TRW Corp.). Under Crawford, Thompson expanded its aircraft-parts manufacturing and helped launch the Cleveland National Air Races.

After testing tree-care concepts in a cemetery, tree preservationist John Davey published “The Tree Doctor in 1903,” detailing a municipality’s neglect of its trees and plant life. The Davey Institute of Tree Surgery (now the Davey Institute, which is part of Davey Tree Expert Co.) was created in 1909 to provide educational resources for its employees.

James C. Davis joined Squire, Sanders & Dempsey in 1946 and initiated the firm’s national growth by opening offices in Washington, D.C., and maneuvering the merger with McAfee. Davis was active in Cleveland’s civic affairs, supporting a visit by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and speaking against racism to the Cleveland Bar Association.

A leader in the modern mall movement, Edward J. DeBartolo established DeBartolo Realty, creating shopping centers such as Boardman Plaza, Southern Park Mall and Randall Park Mall, and developments such as a Seven-Up bottling plant and residential homes for veterans in the 1940s and ‘50s

As Cleveland’s first industrialist Nathaniel Doan was elected one of three highway supervisors during the township’s first elections. He laid out the course of what became Detroit Avenue. He also managed a tavern and operated a baking-soda plant.

In 1900, Cyrus S. Eaton was given a job acquiring electric power franchises. He went on to finance and lead businesses including Republic Steel Co., The Sherwin-Williams Co. and the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. In 1960, Eaton was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize for promoting understanding between the capitalist West and the communist East.

In 1952, Henry F. Eaton and graphic designer John Dix left Industrial Publishing to form Dix & Eaton. Their advertising agency metamorphosed into a public relations firm in the 1970s, gaining a reputation for serving public companies.

In 1911, Joseph O. Eaton Jr. created Torbensen Gear & Axle Co. with Viggo Torbensen in Bloomfield, N.J. In 1915, Eaton moved Torbensen Gear to Cleveland, where it became Eaton Corp., one of the world’s most important automotive parts-makers.

In 1902, Alwin C. Ernst and his brother, Theodore, opened the accounting firm Ernst & Ernst where Alwin revolutionized accounting by packaging data into reports and analyses, providing business managers with information on marketing and business efficiency.

Thomas L. Fawick built a touring sedan, believed to be the first American-made four-door automobile and in 1936, organized Fawick Clutch Co. Fawick clutches were used by major automakers and in the landing gear of naval craft during World War II.

When Harvey Firestone glued rubber to the wheels of carriages from the Columbus Buggy Co., he knew that he had something. Firestone incorporated the Firestone Tire and Rubber Co. in 1900 and partnered with Henry Ford soon after, making tires for his $500 automobile.

John D. Rockefeller’s enthusiasm for the oil business infected Henry M. Flagler, who became a partner in the Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler oil company. Recognizing its potential as a winter vacation spot, Flagler built the 642-mile Florida East Coast Railroad to connect his string of hotels.

Claud H. Foster created the Gabriel Co. in 1904 to manufacture the Gabriel Horn, a car horn he’d invented that was powered by exhaust gases. Foster then created the “Snubber” shock absorber and became well known for his expertise on how cars handled road shock.

In 1929, Tom M. Girdler helped create Republic Steel Corp. and became its first president and board chairman. Under his leadership, the company became a major producer of light alloy steel.

As president of Cleveland Trust from 1908 to 1923, Frederick H. Goff instituted policies and procedures that enhanced the bank’s reputation and financial status. He developed the concepts of the living trust and the community trust and established The Cleveland Foundation in 1914.

In 1882, Caesar A. Grasselli took over his father’s sulfuric acid plant, which moved to Cleveland to be closer to the oil-refining businesses that bought its products. The company built new plants, bought competitors and expanded into other chemicals to become the country’s second-largest producer of zinc.

After living in poverty in Austria-Hungary, Anton Grdina came to Cleveland and opened Grdina & Co., a hardware store in 1904. He helped organize the Slovenian Building and Loan Association and established the North American Building & Savings Co.

George Gund II took over his father’s business in 1916, the Gund Brewing Co. During the Depression, he strengthened his wealth by purchasing high-quality stocks at bargain prices. Gund became director of Cleveland Trust Bank in 1937, its president in 1941 and served as chairman of the board from 1962 to 1966.

In 1891, brothers Salmon P. and Samuel H. Halle purchased a hat and fur business, which they named Halle Bros. By the end of 1910, sales reached $1 million and the store became known for their benevolent and generous attitude toward employees.

In 1832, Truman P. Handy came to Cleveland to oversee the revival of the Commercial Bank of Lake Erie. Handy helped put the bank into receivership during the Panic of 1837. He was also an investor for several rail lines, helped reorganize Western Reserve College and incorporate the Case School of Applied Science.

After managing Theodore Roosevelt’s and William McKinley’s presidential campaigns, Marcus A. Hanna took over his father-in-law’s coal business. The renamed M.A. Hanna Co. became a mining and shipping empire. Hanna was also appointed to the U.S. Senate in 1897, 1898 and 1904.

Under the leadership of H. Stuart Harrison, Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co. increased its ore production fivefold and its earnings per share eightfold, expanded into foreign mining and became the first company to lessen the impact of inflation by tying iron-ore royalties to a price index.

In 1892, Willliam A. Harshaw formed the Cleveland Commercial Co. By 1900, he acquired partners and united his enterprises under the name Harshaw, Fuller & Goodwin Co. During Harshaw’s tenure, the company offered catalysts, ceramics, synthetic crystals and metallic soaps, and was the principal source of refined manganese ore during World War I.

For 40 years, former LTC Corp. chairman and CEO David H. Hoag was influential in the company’s growth and success, and his sales and marketing skills helped save the company from bankruptcy.

Liberty E. Holden bought The Plain Dealer in 1885. Holden’s family owned the paper until 1967, when his heirs sold it to the Newhouse family of New York. Today, it is Cleveland’s only daily newspaper and Ohio’s largest.

Allen C. Holmes is credited with major advancements in corporate law. A national expert in antitrust law, Holmes began his practice in 1944 at what is now Jones Day where he was named managing partner in 1975.

The W.H. Hoover Co. had specialized in leather horse collars until William Henry Hoover developed his vacuum cleaner in response to a friend’s asthma condition. In 1908 Hoover incorporated his Electric Suction Sweeper Co. and by 1919, the vacuum business was flourishing.

George M. Humphrey gave up his $300,000 salary as chairman of Cleveland’s M.A. Hanna Co. for the job of secretary of the Department of the Treasury for $22,500 in 1953. Humphrey also pushed for the creation of National Steel Corp., which grew into the country’s sixth-largest steelmaker.

After selling Pump Engineering Service Corp., William S. Jack and Ralph M. Heintz wooed 25 Cleveland machinists to California to start a company that made airplane starters. Jack & Heintz Inc. moved back to Cleveland and sales leapt to $120 million by 1943.

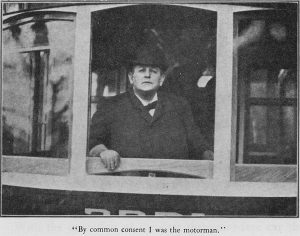

Influenced by Henry George’s “Social Problems,” former businessman Tom L. Johnson ran for public office in 1885 and was elected to the U.S. Congress twice in the 1890s. He was elected mayor four times before his death in 1911.

In 1819, Alfred Kelley was a state representative and chief proponent of a canal linking Lake Erie with the Ohio River. Kelley was instrumental in reviving Cleveland’s banking business and bringing railroads to the area.

In the 1940s, billionaire Fred Lennon met Cullen Crawford, an engineer who developed a pipe fitting dubbed the Swagelock. With a $500 loan, the two founded The Crawford Fitting Co. in 1947. The company, now called Swagelok, has about 3,000 employees and more than 25 facilities on three continents.

Alfred Lerner took over Equitable Bancorp. in 1981, which was acquired by Maryland National Bank. Under Lerner, the bank’s credit card division became MBNA and, in 1991, he took Maryland National Bank public. He and Carmen Policy also brought the beloved Browns back to Cleveland in 1999.

With money he earned building an electric motor for Herbert Henry Dow’s cement mill, John Lincoln started Elliott-Lincoln Electric Co. In 1907, James Lincoln joined his brother as a salesman for the renamed Lincoln Electric. John was also instrumental in establishing Reliance Electric Co.

Under Elmer Lindseth’s 22-year presidency beginning in 1945, Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. grew from serving 357,000 customers to 620,000, and from generating 4.25 billion kilowatt hours of electricity to 12.3 billion. The company accomplished this growth through an aggressive marketing campaign, including a slogan that promoted Cleveland as “The Best Location in the Nation.”

Samuel Mather began his career as an apprentice in his father’s mining firm, the Cleveland Iron Co., which became part of the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co. Mather pioneered the concept of steel-industry integration and bought into steel companies and shipping fleets. When he died in 1931, he was the richest man in Ohio.

Under William G. Mather’s leadership, Cleveland-Cliffs diversified into iron ore-related industries, building charcoal blast furnaces and providing electricity to mining operations. Mather made his greatest contribution to Cleveland’s metal industries in 1930 when he and Cyrus Eaton formed Republic Steel Corp. by combining several steel companies in Youngstown.

Mark H. McCormack, founder, chairman and CEO of Cleveland-based International Management Group, transformed an entire industry and created modern professional sports management in 1960. Today, with 70 offices in 30 countries, IMG is the world’s largest athletic representation firm.

As a Navy officer during World War I, C. Bert McDonald was assigned to Cleveland and fell in love with the city, where he helped build McDonald & Company Investments in 1949. Today, the company still operates under its former chairman’s high ideals: extraordinary responsiveness, reliability and superior customer service.

Ruth Ratner Miller was the first female community-development director of Cleveland’s Department of Health in 1996. She was a civic leader, community advocate and heir to Forest City Enterprises. When Forest City purchased Terminal Tower, she headed the renovation into The Avenue at Tower City.

In 1913, Garrett Morgan organized the G.A. Morgan Hair Redefining Co. to market his hair-straightening compound, which he stumbled upon while mixing a solution to better lubricate sewing-machine needles at his sewing-machine shop. He also patented products such as the gas mask and the three-color traffic light.

In 1888, Liberty Holden loaned George Myers $2,000 to open a barbershop in the Hollenden House Hotel, a hub for the rich and powerful. Myers was a well-known political player. When Marcus Hanna needed votes for a Senate seat, Myers bribed Cleveland legislator William A. Clifford and procured an illegal victory for Hanna.

Charles A. Otis Jr. was known as “Mr. Cleveland” for contributing to the city’s growth in the first half of the 20th century. A steel salesman, Otis joined Addison Hough in 1895, then created the Otis & Hough partnership, an independent sales representative for large steel companies.

After one bankruptcy, Arthur L. Parker built Parker Appliance Co. into the world’s largest manufacturer of airplane parts. Parker died in 1945 and his widow, Helen, recruited S. Blackwell Taylor and Robert W. Cornell to help rebuild the company. In 1957, Parker Appliance acquired Hannifin Manufacturing Co. and Parker Hannifin Corp. was born.

Pat Parker’s insatiable curiosity led him to innovations, ideas and opportunities that allowed him to build Parker Hannifin Corp. from a $197 million mid-level manufacturer to a $2.5 billion global industrial maker of motion and control technologies by the time he retired in 1994.

Lionel A. Pile emigrated from Barbados to the United States in 1900. When Pile’s brother-in-law, O.H. Lewis, became ill, Pile took over his bakery, Hough Bakery. By 1927, he began adding one store each year for the next 20 years.

Leonard Ratner and his brothers Charles, Harry and Max bought a lumberyard called Buckeye Lumber in the 1920s. Renamed Forest City Materials Co., the company turned the lumberyard into home-improvement stores. Max and Leonard moved into the development business on their own before turning Forest City Enterprises over to their children in the 1970s.

During John W. “Jack” Reavis’ tenure at Jones, Day, Reavis & Pogue, the firm grew from 50 to 173 lawyers, and established its national reputation and scope in the 1960s. Reavis founded the Interracial Business Men’s Committee to defuse violence and racial tension and earned the Cleveland Medal for Public Service and the NAACP’s Human Rights Award.

After the three Richman brothers took over their father’s factory at East 55th Street in 1893, Richman Bros. became the first garment maker to sell “direct from the factory.” Their first retail store opened in 1903 and in 1907, the brothers opened additional retail outlets selling factory-produced men’s clothing directly to the customer.

J. French Robinson headed East Ohio Gas Co. when, in 1944, an explosion caused by ruptured liquefied-gas tanks killed 131 people. Robinson and his company earned the community’s respect for their willingness to fairly settle the claims arising from the disaster. During World War II, Robinson oversaw the allocation of natural gas for the Petroleum Industry War Council.

Larry Robinson took over his father’s business, J.B. Robinson Jewelers, when he died in the late 1950s. At its height, the chain included almost 100 stores in 12 states.

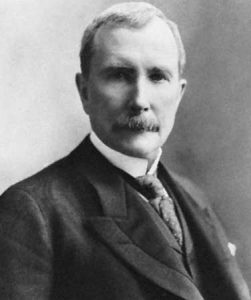

John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Co. was the most powerful business organization in the country in the 1890s. He also made a lasting impact on Cleveland. The Rockefeller building was the city’s first skyscraper. The Rockefeller family made numerous gifts of money and land to Greater Cleveland, including Rockefeller Park and Forest Hill Park.

Maurice Saltzman, president of Bobbie Brooks Inc., founded Ritmore Sportswear Inc. in 1939. Bobbie Brooks grew to become one of the country’s largest clothing makers in the 1950s and ’60s. Its 120-person sales force went directly to 6,000 small-town shops and sold the company’s clothing line.

Jacob Sapirstein founded the Sapirstein Greeting Card Co., in 1932. In 1952, Sapirstein took the company public as American Greetings Corp. Today, American Greetings is the largest publicly held manufacturer of greeting cards and related gift items in the world.

In 1870, Henry A. Sherwin, Alanson T. Osborn and Edward Williams opened Sherwin-Williams & Co.’s first headquarters at 126 Superior St. They developed the world’s first reliable ready-mixed paint. By 1890, the company had enjoyed its first million-dollar sales year.

Bernie Shulman bought the 41-store Standard Drug chain in Cleveland for $2 million in 1962 and converted it to a self-serve, discount concept he developed with several partners, later known as Revco drug stores. In 1975, he opened Bernie Shulman’s, possibly the nation’s first “deep-discount” drug store.

Harry C. Smith helped found The Cleveland Gazzette in 1883 before serving three terms as a state representative and becoming the first black candidate for Ohio governor in 1926. As a legislator, Smith successfully sponsored The Ohio Civil Rights Act of 1894 and the Mob Violence Act of 1896.

The Smith brothers were the children of Dr. Albert W. Smith, who helped found the Dow Chemical Corp. Kelvin, the youngest, and Francis Nason developed the first compressed-air applicator in 1928. Older brothers Kent and Vincent brought their chemical-engineering and law degrees to the ventures. The result: Graphite Oil Products, later renamed The Lubrizol Corp.

Andrew Squire formed the world-class law firm of Squire, Sanders & Dempsey in 1890. Squire incorporated Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. and what would become Union Carbide Corp., among other concerns.

In 1850, state Rep. Alfred E. Kelley asked Amasa Stone to build the Cleveland-to-Columbus link of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad. Stone did the building and became president of the line. He subsequently built and headed the Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula and the Chicago & Milwaukee lines.

Though his father, Jacob Sapirstein, started American Greetings Corp., it was Irving I. Stone who suggested the company could accrue more profit by printing and distributing its own line of cards. Stone helped expand the fledgling enterprise’s sales efforts and helped his family grow the company into the international greeting-card giant that by 1940 recorded sales of $1 million.

“It means a lot when a downtown is alive,” said Herbert Strawbridge, former CEO of the Higbee Co. This philosophy inspired Strawbridge’s Cleveland business ventures, including the success of Higbee’s, and what became the modern-day Flats in the 1970s.

Vernon B. Stouffer opened the first of a chain of restaurants called Stouffer’s Lunch with his father. Joined by his brother Gordon in 1925, Stouffer elevated the family lunch-counter trade into a national chain of restaurants, motor inns and food-service operations. In 1954, Stouffer’s opened a production plant in Solon.

Machinists Ambrose Swasey and Worcester R. Warner shared a fascination for telescopes and optical equipment and set up their own machine-tool business in Chicago in 1880. They came to Cleveland in 1881 and in the next 100 years, their company, Warner & Swasey Co., became known worldwide for its turret lathes and telescopes.

George Jackson “Jack” Tankersley served as chairman of East Ohio Gas Co. in 1973 and chairman of Consolidated Natural Gas, East Ohio’s parent company. Tankersley increased the company’s gas production, automated services and stepped up gas and oil exploration at CNG. During the energy crisis of the mid-1970s, he spoke out on the need for price deregulation and energy conservation.

Frank E. Taplin founded Cleveland and Western Coal Co. (later renamed North American Coal Corp.) with his brother, Charles, in 1912. As his company acquired mines, Taplin began using railroads to ship his raw materials. He purchased the Pittsburgh & West Virginia line in 1923.

In the late 1800s, Sophie Strong Taylor, widow to John Livingstone Taylor, ran the William Taylor & Son Co. Her religious convictions guided her management for 44 years. She insisted the store be closed on Sundays and carry Bibles in every language that was spoken in Cleveland’s melting pot.

The Taylor Chair Co., founded by William O. Taylor, dates back to Bedford Township chair-maker Benjamin Fitch. In 1816, Fitch started making a “splint-bottom chair.” Taylor started working with Fitch and in 1844 began the W.O. Taylor Chair Factory.

In 1905, Charles E. Thompson bought controlling interest in the company that would later be known as TRW Inc. At the time, what was then Cleveland Cap Screw Co. was a modest operation specializing in welding automobile chassis and bicycle parts. Thompson infused the company with his technological vision, making TRW a world leader in precision-engineered automotive and aerospace components.

After he entered the Ohio Bar in 1827, David Tod’s first major business investment was to build a canal connecting the Ohio and Erie Canal with the Ohio River, breathing life into Mahoning Valley. Tod was elected president of the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad, became postmaster of Warren and was elected to the Ohio Senate and appointed minister to Brazil by President Polk.

Richard Tullis moved to Cleveland in 1956 to become vice president of Harris Intertype Corp. (now Harris Corp.). During his tenure as chairman, president and CEO, the company grew from $41 million to $2 billion in sales.

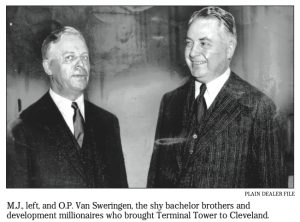

Creators of Shaker Heights and the Terminal Tower, brothers Oris P. and Mantis J. Van Sweringen reshaped Cleveland and started the march to the suburbs in the late 1800s. They bought lots in the Shaker area and built their own streetcar line into the new community.

In 1854, Jeptha Wade negotiated a merger that consolidated telegraph routes covering the five states north of the Ohio River into the Speed & Wade Telegraph Lines. The company became the Western Union Telegraph Co., providing the first consistent long-distance communication. Wade moved to Cleveland in 1856 to serve as the system’s general agent.

Raymond John Wean created the Wean Engineering Co. in 1929, and became an influential powerhouse in the production of steel. The mill equipment Wean Engineering developed and manufactured helped revolutionize steel production in America. His name appears on more than 25 patents, and his machines helped combine and improve mill processes.

A giant among the city’s technological wizards, Samuel T. Wellman patented his open-hearth, iron-melting furnace charging machine and launched a new era in steel making. In 1896, Wellman, along with his brother Charles and John W. Seaver, formed the Wellman-Seaver Engineering Co., later the Wellman-Seaver-Morgan Co.

In 1935, the Westropp sisters were the co-founders of what was to become the Women’s Federal Savings Bank, the first savings and loan association in the world to be created, managed and staffed almost entirely by women.

In 1900, Rollin White’s company, the White Motor Co., produced its first car — the White Steamer — and first truck. After his father died in 1914, White left the company. Two years later he organized Cleveland Tractor Co., designing many tractors himself, while running the company.

Thomas H. White invented a hand-operated, single-thread sewing machine and, in 1866, brought his White Manufacturing Co. to Cleveland for better access to materials and machining skills. Within 10 years, the company became known as White Sewing Machine Co. and Cleveland had become the world center of the sewing-machine industry.

Alexander Winton made Cleveland the center of the American automobile-manufacturing industry. By 1898, the Winton Motor Carriage Co. was cranking out the first standard-production cars made in America. To assuage public doubt about his vehicle’s safety and reliability, Winton drove from Cleveland to New York in 1899 and made the first coast-to-coast automobile trip.

Bart Wolstein’s imprint is all over Northeast Ohio. Through his real estate development companies, Wolstein not only built more than 100 shopping centers nationwide, but is responsible for the Renaissance office building in Cleveland, Barrington Golf Club in Aurora, Glenmoor Country Club near Canton and the Bertram Inn & Conference Center in Aurora.

In 1834, George Worthington came to Cleveland from Utica, N.Y., planning to tap the new market for hardware that Ohio Canal construction was creating. Worthington quickly became a millionaire supplying the construction workers’ needs. The company’s growth was entirely internally generated: Worthington didn’t believe in mergers.

The third African-American to receive a degree from Antioch College, J. Walter Wills Sr. became a partner in the Gee & Wills Funeral Co. in 1904. When the partnership dissolved, he opened J.W. Wills & Sons and moved to East 55th Street, calling it the House of Wills. Wills also helped organize the Cleveland Board of Trade, the city’s first organization of African-American businesses.