Cleveland 1912: Civitas Triumphant By Dr. John Grabowski

Mark Hanna: The Clevelander Who Made a President By Joe Frolik

Rockefeller’s Right-Hand Man: Henry Flagler By Michael D. Roberts

Cleveland’s Original Black Leader: John O. Holly By Mansfield Frazier

The Heart of Amasa Stone By John Vacha

Frederic C. Howe: Making Cleveland the City Beautiful (Or At Least Trying) by Marian Morton

Bill Veeck: The Man Who Conquered Cleveland and Changed Baseball Forever By Bill Lubinger

When Cleveland Saw Red By John Vacha

Maurice Maschke: The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland by Brent Larkin

Inventor Garrett Morgan, Cleveland’s Fierce Bootstrapper by Margaret Bernstein

How Cleveland Women Got the Vote and What They Did With It by Marian Morton

One Man Can Make a Difference by Roldo Bartimole

The Election That Changed Cleveland Forever by Michael D. Roberts

Deferring Dreams: Racial and Religious Covenants in Shaker Heights, Cleveland Heights and East Cleveland, 1925 to 1970 By Marian Morton

Cyrus Eaton: Khrushchev’s Favorite Capitalist By Jay Miller

Ray Shepardson: The Man Who Relit Playhouse Square By John Vacha

Bertha Josephine Blue By Debbi Snook

The Scourge of Corrupt and Inefficient Politicians: The Citizens League of Greater Cleveland By Marian Morton

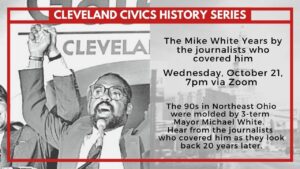

The Man Who Saved Cleveland By Michael D. Roberts and Margaret Gulley

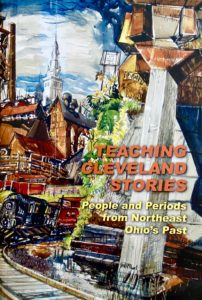

cover image by Moses Pearl. Use thanks to Stuart Allen Pearl. http://www.artistsarchives.org/archived_artist/moses-pearl/

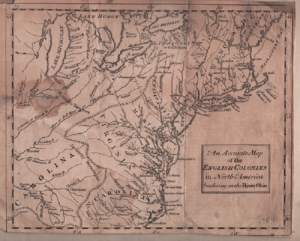

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175

(Map of English Colonies Bordering on Ohio River 175